Biology:Negative-strand RNA virus

| Negarnaviricota | |

|---|---|

| |

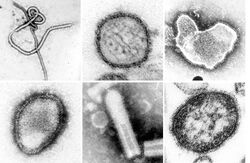

| A montage of transmission electron micrographs of some viruses in the phylum Negarnaviricota. Not to scale. Species from left to right, top to bottom: Zaire ebolavirus, Sin Nombre orthohantavirus, Human orthopneumovirus, Hendra henipavirus, an unidentified rhabdovirus, Measles morbillivirus. | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Subtaxa | |

|

See text | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Negative-strand RNA viruses (−ssRNA viruses) are a group of related viruses that have negative-sense, single-stranded genomes made of ribonucleic acid (RNA). They have genomes that act as complementary strands from which messenger RNA (mRNA) is synthesized by the viral enzyme RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). During replication of the viral genome, RdRp synthesizes a positive-sense antigenome that it uses as a template to create genomic negative-sense RNA. Negative-strand RNA viruses also share a number of other characteristics: most contain a viral envelope that surrounds the capsid, which encases the viral genome, −ssRNA virus genomes are usually linear, and it is common for their genome to be segmented.

Negative-strand RNA viruses constitute the phylum Negarnaviricota, in the kingdom Orthornavirae and realm Riboviria. They are descended from a common ancestor that was a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) virus, and they are considered to be a sister clade of reoviruses, which are dsRNA viruses. Within the phylum, there are two major branches that form two subphyla: Haploviricotina, whose members are mostly non-segmented and which encode an RdRp that synthesizes caps on mRNA, and Polyploviricotina, whose members are segmented and which encode an RdRp that snatches caps from host mRNAs. A total of six classes in the phylum are recognized.

Negative-strand RNA viruses are closely associated with arthropods and can be informally divided between those that are reliant on arthropods for transmission and those that are descended from arthropod viruses but can now replicate in vertebrates without the aid of arthropods. Prominent arthropod-borne −ssRNA viruses include the Rift Valley fever virus and the tomato spotted wilt virus. Notable vertebrate −ssRNA viruses include the Ebola virus, hantaviruses, influenza viruses, the Lassa fever virus, and the rabies virus.

Etymology

Negarnaviricota takes the first part of its name from Latin nega, meaning negative, the middle part rna refers to RNA, and the final part, -viricota, is the suffix used for virus phyla. The subphylum Haploviricotina takes the first part of its name, Haplo, from Ancient Greek ἁπλός, meaning simple, and -viricotina is the suffix used for virus subphyla. The subphylum Polyploviricotina follows the same pattern, Polyplo being taken from Ancient Greek πολύπλοκος, meaning complex.[1]

Characteristics

Genome

All viruses in Negarnaviricota are negative-sense, single-stranded RNA (−ssRNA) viruses. They have genomes made of RNA, which are single instead of double-stranded. Their genomes are negative sense, meaning that messenger RNA (mRNA) can be synthesized directly from the genome by the viral enzyme RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), also called RNA replicase, which is encoded by all −ssRNA viruses. Excluding viruses in the genus Tenuivirus and some in the family Chuviridae, all −ssRNA viruses have linear rather than circular genomes, and the genomes may be segmented or non-segmented.[1][3][4] All −ssRNA genomes contain terminal inverted repeats, which are palindromic nucleotide sequences at each end of the genome.[5]

Replication and transcription

Replication of −ssRNA genomes is executed by RdRp, which initiates replication by binding to a leader sequence on the 3'-end (usually pronounced "three prime end") of the genome. RdRp then uses the negative sense genome as a template to synthesize a positive-sense antigenome. When replicating the antigenome, RdRp first binds to the trailer sequence on the 3'-end of the antigenome. Thereafter, RdRp ignores all transcription signals on the antigenome and synthesizes a copy of the genome while using the antigenome as a template.[6] Replication is executed while the genome is inside the nucleocapsid, and RdRp unveils the capsid and translocates along the genome during replication. As new nucleotide sequences are synthesized by RdRp, capsid proteins are assembled and encapsidate the newly replicate viral RNA.[2]

Transcribing mRNA from the genome follows the same directional pattern as producing the antigenome. At the leader sequence, RdRp synthesizes a 5-'end (usually pronounced "five prime end") triphosphate-leader RNA and either, in the case of the subphylum Haploviricotina, caps the 5'-end or, in the case of the subphylum Polyploviricotina, snatches a cap from a host mRNA and attaches it to the viral mRNA so that the mRNA can be translated by the host cell's ribosomes.[7][8][9]

After capping the mRNA, RdRp initiates transcription at a gene start signal and later terminates transcription upon reaching a gene end signal.[10] At the end of transcription, RdRp synthesizes a polyadenylated tail (poly (A) tail) consisting of hundreds of adenines in the mRNA's 3-end, which may be done by stuttering on a sequence of uracils.[11][12] After the poly (A) tail is constructed, the mRNA is released by RdRp. In genomes that encode more than one transcribable portion, RdRp can continue scanning to the next start sequence to continue with transcription.[10][7][13]

Some −ssRNA viruses are ambisense, meaning that both the negative genomic strand and positive antigenome separately encode different proteins. In order to transcribe ambisense viruses, two rounds of transcription are performed: first, mRNA is produced directly from the genome; second, mRNA is created from the antigenome. All ambisense viruses contain a hairpin loop structure to stop transcription after the protein's mRNA has been transcribed.[14]

Morphology

Negative-strand RNA viruses contain a ribonucleoprotein complex composed of the genome and an RdRp attached to each segment of the genome surrounded by a capsid.[15] The capsid is composed of proteins whose folded structure contains five alpha-helices in the N-terminal lobe (5-H motif) and three alpha-helices in the C-terminal lobe (3-H motif). Inside the capsid, the genome is sandwiched between these two motifs.[2] Excluding the family Aspiviridae, −ssRNA viruses contain an outer viral envelope, a type of a lipid membrane that surrounds the capsid. The shape of the virus particle, called a virion, of −ssRNA viruses varies and may be filamentous, pleomorphic, spherical, or tubular.[16]

Evolution

Genome segmentation is a prominent trait among many −ssRNA viruses, and −ssRNA viruses range from having genomes with one segment, typical for members of the order Mononegavirales, to genomes with ten segments, as is the case for Tilapia tilapinevirus.[5][17] There is no clear trend over time that determines the number of segments, and genome segmentation among −ssRNA viruses appears to be a flexible trait since it has evolved independently on multiple occasions. Most members of the subphylum Haploviricotina are nonsegmented, whereas segmentation is universal in Polyploviricotina.[2][5]

Phylogenetics

Phylogenetic analysis based on RdRp shows that −ssRNA viruses are descended from a common ancestor and that they are likely a sister clade of reoviruses, which are dsRNA viruses. Within the phylum, there are two clear branches, assigned to two subphyla, based on whether RdRp synthesizes a cap on viral mRNA or snatches a cap from host mRNA and attaches that cap to viral mRNA.[1][3]

Within the phylum, −ssRNA viruses that infect arthropods appear to be basal and the ancestors of all other −ssRNA viruses. Arthropods frequently live together in large groups, which allows for viruses to be transmitted easily. Over time, this has led to arthropod −ssRNA viruses gaining a high level of diversity. While arthropods host large quantities of viruses, there is disagreement about the degree to which cross-species transmission of arthropod −ssRNA viruses occurs among arthropods.[4][5]

Plant and vertebrate −ssRNA viruses tend to be genetically related to arthropod-infected viruses. Furthermore, most −ssRNA viruses outside of arthropods are found in species that interact with arthropods. Arthropods therefore serve as both key hosts and vectors of transmission of −ssRNA viruses. In terms of transmission, non-arthropod −ssRNA viruses can be distinguished between those that are reliant on arthropods for transmission and those that can circulate among vertebrates without the aid of arthropods. The latter group is likely to have originated from the former, adapting to vertebrate-only transmission.[5]

Classification

Negarnaviricota belongs to the kingdom Orthornavirae, which encompasses all RNA viruses that encode RdRp, and the realm Riboviria, which includes Orthornavirae as well as all viruses that encode reverse transcriptase in the kingdom Pararnavirae. Negarnaviricota contains two subphyla, which contain a combined six classes, five of which are monotypic down to lower taxa:[2][9][18]

- Subphylum: Haploviricotina, which contains −ssRNA viruses that encode an RdRp that synthesizes a cap structure on viral mRNA and which usually have nonsegmented genomes

- Class: Chunquiviricetes

- Order: Muvirales

- Family: Qinviridae

- Genus: Yingvirus

- Family: Qinviridae

- Order: Muvirales

- Class: Milneviricetes

- Order: Serpentovirales

- Family: Aspviridae

- Genus: Ophiovirus

- Family: Aspviridae

- Order: Serpentovirales

- Class: Monjiviricetes

- Class: Yunchangviricetes

- Order: Goujianvirales

- Family: Yueviridae

- Genus: Yuyuevirus

- Family: Yueviridae

- Order: Goujianvirales

- Class: Chunquiviricetes

- Subphylum: Polyploviricotina, which contains −ssRNA viruses that encode an RdRp that takes a cap from host mRNA to use as the cap on viral mRNA and which have segmented genomes

- Class: Ellioviricetes

- Order: Bunyavirales

- Class: Insthoviricetes

- Order: Articulavirales

- Class: Ellioviricetes

Negative-strand RNA viruses are classified as Group V in the Baltimore classification system, which groups viruses together based on their manner of mRNA production and which is often used alongside standard virus taxonomy, which is based on evolutionary history. Therefore, Group V and Negarnaviricota are synonymous.[1]

Disease

Negative-strand RNA viruses caused many widely known diseases. Many of these are transmitted by arthropods, including the Rift Valley fever virus and the tomato spotted wilt virus.[19][20] Among vertebrates, bats and rodents are common vectors for many viruses, including the Ebola virus and the rabies virus, transmitted by bats and other vertebrates,[21][22] and the Lassa fever virus and hantaviruses, transmitted by rodents.[23][24] Influenza viruses are common among birds and mammals.[25] Human-specific −ssRNA viruses include the measles virus and the mumps virus.[26][27]

History

Many diseases caused by −ssRNA viruses have been known throughout history, including hantavirus infection, measles, and rabies.[28][29][30] In modern history, some such as Ebola and influenza have caused deadly disease outbreaks.[31][32] The vesicular stomatitis virus, first isolated in 1925 and one of the first animal viruses to be studied because it could be studied well in cell cultures, was identified as an −ssRNA virus, which was unique at the time because other RNA viruses that had been discovered were positive sense.[33][34] In the early 21st century, the bovine disease rinderpest, caused by −ssRNA rinderpest virus, became the second disease to be eradicated, after smallpox, caused by a DNA virus.[35]

In the 21st century, viral metagenomics has become common to identify viruses in the environment. For −ssRNA viruses, this allowed for a large number of invertebrate, and especially arthropod, viruses to be identified, which helped to provide insight into the evolutionary history of −ssRNA viruses. Based on phylogenetic analysis of RdRp showing that −ssRNA viruses were descended from a common ancestor, Negarnaviricota and its two subphyla were established in 2018, and it was placed into the then newly established realm Riboviria.[1][36]

Gallery

Hantavirus (Hantaviridae)

Mumps virus (Paramyxoviridae)

Parainfluenza (Paramyxoviridae)

Vesicular stomatitis virus (Rhabdoviridae)

Notes

- ↑ The hepatitis D virus is often called a virus but can be more specifically described as a virusoid-like pathogenic −ssRNA strand. It is excluded from Negarnaviricota because although it is −ssRNA, it does not encode RdRp, which is the unifying trait of viruses in Orthornavirae.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Megataxonomy of negative-sense RNA viruses" (in en) (docx). 21 August 2017. https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/2017.006M.A.v2.Negarnaviricota.zip.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Nucleocapsid Structure of Negative Strand RNA Virus". Viruses 12 (8): 835. 30 July 2020. doi:10.3390/v12080835. PMID 32751700.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Origins and Evolution of the Global RNA Virome". mBio 9 (6): e02329-18. 27 November 2018. doi:10.1128/mBio.02329-18. PMID 30482837.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Re-assessing the diversity of negative strand RNA viruses in insects". PLOS Pathog 15 (12): e1008224. 12 December 2019. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008224. PMID 31830128.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses". eLife 4 (4): e05378. 29 January 2015. doi:10.7554/eLife.05378. PMID 25633976.

- ↑ "Negative stranded RNA virus replication". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. https://viralzone.expasy.org/1096.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Negative-stranded RNA virus transcription". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. https://viralzone.expasy.org/1917.

- ↑ "Cap snatching". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. https://viralzone.expasy.org/839?outline=all_by_species.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Classify viruses - the gain is worth the pain". Nature 566 (7744): 318–320. February 2019. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00599-8. PMID 30787460. Bibcode: 2019Natur.566..318K. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-00599-8. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fearns, Rachel; Plemper, Richard K (2017-04-15). "Polymerases of paramyxoviruses and pneumoviruses". Virus Research 234: 87–102. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.008. ISSN 0168-1702. PMID 28104450.

- ↑ Harmon, Shawn B.; Megaw, A. George; Wertz, Gail W. (2001-01-01). "RNA Sequences Involved in Transcriptional Termination of Respiratory Syncytial Virus". Journal of Virology 75 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.1.36-44.2001. PMID 11119571.

- ↑ Jacques, J. P.; Kolakofsky, D. (1991-05-01). "Pseudo-templated transcription in prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms." (in en). Genes & Development 5 (5): 707–713. doi:10.1101/gad.5.5.707. ISSN 0890-9369. PMID 2026325. http://genesdev.cshlp.org/content/5/5/707.

- ↑ "Negative-stranded RNA virus polymerase stuttering". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. https://viralzone.expasy.org/1916.

- ↑ "Ambisense transcription in negative stranded RNA viruses". Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. https://viralzone.expasy.org/1945.

- ↑ "Structural perspective on the formation of ribonucleoprotein complex in negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses". Trends Microbiol 21 (9): 475–484. September 2013. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2013.07.006. PMID 23953596.

- ↑ Fermin, G. (2018). Viruses: Molecular Biology, Host Interactions and Applications to Biotechnology. Elsevier. pp. 19–27, 43. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-811257-1.00002-4. ISBN 9780128112571. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128112571000024.

- ↑ "Characterization of a Novel Orthomyxo-like Virus Causing Mass Die-Offs of Tilapia". mBio 7 (2): e00431-16. 5 April 2016. doi:10.1128/mBio.00431-16. PMID 27048802.

- ↑ "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. https://ictv.global/taxonomy.

- ↑ "Rift Valley Fever". Clin Lab Med 37 (2): 285–301. June 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.01.004. PMID 28457351.

- ↑ "Top 10 plant viruses in molecular plant pathology". Mol Plant Pathol 12 (9): 938–954. December 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00752.x. PMID 22017770.

- ↑ "Ebola Virus Disease in Humans: Pathophysiology and Immunity". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 411: 141–169. 2017. doi:10.1007/82_2017_11. ISBN 978-3-319-68946-3. PMID 28653186.

- ↑ "The spread and evolution of rabies virus: conquering new frontiers". Nat Rev Microbiol 16 (4): 241–255. April 2018. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2018.11. PMID 29479072.

- ↑ "Pathogenesis of Lassa fever". Viruses 4 (10): 2031–2048. 9 October 2012. doi:10.3390/v4102031. PMID 23202452.

- ↑ "Hantavirus infections". Clin Microbiol Infect 21S: e6–e16. April 2019. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12291. PMID 24750436. https://www.clinicalmicrobiologyandinfection.com/article/S1198-743X(15)00536-4/fulltext. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ "Animal influenza virus infections in humans: A commentary". Int J Infect Dis 88: 113–119. November 2019. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2019.08.002. PMID 31401200. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(19)30327-3/fulltext. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ "Transmission of Measles". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 February 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/transmission.html.

- ↑ "Molecular biology, pathogenesis and pathology of mumps virus". J Pathol 235 (2): 242–252. January 2015. doi:10.1002/path.4445. PMID 25229387.

- ↑ "Hantavirus infection: a global zoonotic challenge". Virol Sin 32 (1): 32–43. 2017. doi:10.1007/s12250-016-3899-x. PMID 28120221.

- ↑ "Measles history". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 5 February 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html.

- ↑ "The history of rabies in the Western Hemisphere". Antiviral Res 146: 221–232. October 2017. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.013. PMID 28365457.

- ↑ "General introduction into the Ebola virus biology and disease". Folia Med Cracov 54 (3): 57–65. 2014. PMID 25694096. http://www.fmc.cm-uj.krakow.pl/pdf/54_3_57.pdf. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ "Influenza". Nat Rev Dis Primers 4 (1): 3. 28 June 2018. doi:10.1038/s41572-018-0002-y. PMID 29955068.

- ↑ "Vesicular stomatitis virus". Center for Food Security and Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, Iowa State University. November 2015. https://www.swinehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Vesicular-stomatitis-virus-VSV.pdf.

- ↑ "A short biased history of RNA viruses". RNA 21 (4): 667–669. April 2015. doi:10.1261/rna.049916.115. PMID 25780183. PMC 4371325. https://rnajournal.cshlp.org/content/21/4/667.long. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ "The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369 (1645): 20130433. 12 May 2014. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0433. PMID 24821919.

- ↑ "ICTV Taxonomy history: Negarnaviricota". https://ictv.global/taxonomy/taxondetails?taxnode_id=201906016.

Further reading

- Ward, C. W. (1993). "Progress towards a higher taxonomy of viruses". Research in Virology 144 (6): 419–53. doi:10.1016/S0923-2516(06)80059-2. PMID 8140287.

Wikidata ☰ Q57737752 entry

|