Medicine:Pick's disease

This article may be incomprehensible or very hard to understand. (January 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Pick's disease | |

|---|---|

| |

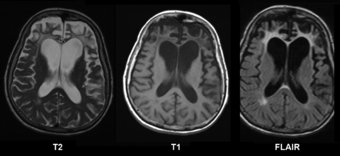

| Brain MRI in Pick's disease | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

Pick's disease (FTD, frontotemporal dementia) is a specific pathology that is one of the causes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. It is also known as Pick disease and PiD. A defining characteristic of the disease is build-up of tau proteins in neurons, accumulating into silver-staining, spherical aggregations known as "Pick bodies".[1] Common symptoms noticed early are personality and emotional changes and deterioration of language.

Pick's disease traditionally was a group of neurodegenerative diseases with symptoms attributable to frontal and temporal lobe dysfunction. This condition is now more commonly called frontotemporal dementia by professionals, and the use of "Pick's disease" as a clinical diagnosis has fallen out of fashion. These two uses have previously led to confusion among professionals and patients.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of Pick's disease include difficulty in language and thinking, efforts to dissociate from family, behavioral changes, unwarranted anxiety, irrational fears, compulsive buying disorder (CBD or oniomania), impaired regulation of social conduct (e.g., breaches of etiquette, vulgar language, tactlessness, disinhibition, misperception), passivity, low motivation (aboulia), inertia, overactivity, pacing, and wandering.[2] A characteristic of Pick’s disease is that dysfunctional, argumentative, or hostile social conduct is initially exhibited towards family members and not initially exhibited in a workplace or neutral environment. PiD is highly hereditary.[3] The changes in personality allow doctors to distinguish between PiD and Alzheimer disease.[4] Pick's disease is one of the causes of the clinical syndrome of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, which has three subtypes. PiD pathology is associated more with the frontotemporal dementia and progressive nonfluent aphasia subtypes than the semantic dementia subtype.

Causes

While other pathologies causing frontotemporal lobar degeneration are associated with a genetic cause, evidence is not conclusive in modern research on whether classical PiD pathology has or does not have a direct genetic link, or whether it has been shown to run in families or certain ethnic- or gender-specific subgroups. However, excess of a protein called β-amyloid (Aβ) in neural cells has been linked to neural degeneration. A buildup of Aβ within cells causes inflammation, leading to cell destruction by the immune system.[5] Proteins associated with Pick's disease are present in all nerve cells, but those with the disease have an abnormal amount.[4]

Mutations in the tau gene (MAPT) have been associated with this disease.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

PiD was first recognized as a distinct disease separate from other neurodegenerative diseases because of the presence of large, dark-staining aggregates of proteins in neurological tissue, as well as the aforementioned ballooned cells, which are known as Pick cells. Pick bodies are almost universally present in patients with PiD, but some new cases of atypical PiD have come to light that lack noticeable Pick bodies.[8] A variety of stains can aid in the visualization of Pick bodies and Pick cells, but immunohistochemical staining using anti-tau and anti-ubiquitin antibodies have proven the most efficient and specific.[9] Hematoxylin and eosin staining allows visualization of another population of Pick cells, which are both tau and ubiquitin protein negative. Several silver impregnation stains have been used, including the Bielschowsky, Bodian, and Gallyas methods.[8][10] The latter two techniques are sensitive enough to allow PiD to be distinguished from AD, as the Bodian will bind preferentially to cells with PiD as compared to the Gallyas method, which preferentially binds to the cells with Alzheimer's.[10]

Numerous areas of the brain are affected by PiD, but the specific areas affected allow for differentiation between PiD and AD. Pick bodies are almost always found in several places in the brain, including the dentate gyrus, the pyramidal cells of the CA1 sector and subiculum of the hippocampus, and the neocortex as well as a plurality of other nuclei. The location in the layers of the brain, as well as the anatomical placement, demonstrates some of the unique features of PiD. A striking feature is that in the neocortex the Pick bodies are in the II and IV layers of the cortex, which send neurons within the cortex and to thalamic synapses, respectively. While layers III and V have very few if any Pick bodies, they show extreme neuronal loss that can, in some cases, be so severe as to leave a void in the brain altogether. Other regions involved include the caudate, which is severely affected, the dorsomedial region of the putamen, the globus pallidus, and locus coeruleus.[1] The hypothalamic lateral tuberal nucleus is also very severely affected. The cerebellar elements that are important in receiving input, including the mossy fibers and the monodendritic brush cells in the granule cell layer, and generating output signals, most notably the dentate nucleus, are stricken with tau protein inclusions. Strangely, the substantia nigra is most often uninvolved or only mildly involved, but cases of extreme degeneration do exist.[1]

PiD has several unique biochemical characteristics that allow for its identification as opposed to other pathological subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. The most striking of these is that this disease, which has tau protein tangles present in many affected neurons, contains only one or as many as two of the six isoforms of the tau protein.[11] All of these isoforms result from alternative splicing of the same gene.[12] Pick bodies typically have the 3R isoform of tau proteins as not only the most abundant form but the only form of this protein, but some studies have shown that a much greater number of tau isoforms including 4R and mixed 3R/4R can be present in the Pick bodies.[13][14] Not only do these tangles have the 3R tau protein predominately, they are characteristically shaped with a round body; there is often an indentation in the area that faces the nucleus of the cell.

The Pick bodies are able to be labeled by N-terminal amyloid precursor protein segment, hyperphosphorylated tau, ubiquitin, Alz-50, neurofiliment proteins, clathrin, synaptophysin[9] and neuronal surface glycoside (A2B5)[13] specific stains. Moreover, βII tubulin proteins are suspected in playing a role in the formation of phosphor-tau aggregates that are seen in PiD as well as AD.[15]

Differences from Alzheimer’s disease

In Alzheimer's disease, all six isoforms of tau proteins are expressed. In addition, the presence of neurofibrillary tangles that are a hallmark of AD can be stained with antibodies to basic fibroblast growth factor, amyloid P, and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan.[13]

Another difference is that in PiD, a personality change occurs before any form of memory loss, unlike AD, where memory loss typically presents first. This is used clinically to determine whether a patient is suffering from AD or PiD.

Diagnosis

The confirmatory diagnosis is made by brain biopsy, but other tests can be used to help, such as MRI, EEG, CT, and physical examination and history.[16]

Management

Pick's disease, unfortunately, has a rapidly progressing, insidious course with steady deterioration over roughly 4 years. This time can vary by individual, but many patients' quality of life decreases and fatality generally occurring (on average) 4 years from diagnosis. No known cure exists for Pick's disease and many AD treatments have less utility in this patient population.[17] Treatment is symptomatic with different physicians using different treatment regimens for the illness; some recommend no treatment so as to do no harm. Other physicians may recommend a trial of a medication to improve mood symptoms, and cognitive exercises to attempt to slow decline.

History

PiD is named after Arnold Pick, a professor of psychiatry from Charles University in Prague, who first discovered and described the disease in 1892 by examining the brain tissue of several deceased patients with histories of dementia.[1][18] As a result, the characteristic histological feature of this disease—a protein tangle that appears as a large body in neuronal tissue—is named a Pick body. In 1911, Alois Alzheimer noted the complete absence of senile plaques and neurofilbrillary tangles, as well as the presence of Pick bodies and occasional ballooned neurons.[18]

Notable cases

- Don Cardwell (1935–2008), Major League Baseball pitcher[19]

- Jerry Corbetta (1947–2016), frontman, organist and keyboardist of American psychedelic rock band Sugarloaf[20]

- Ted Darling (1935–1996), Buffalo Sabres television announcer

- Robert W. Floyd (1936–2001), computer scientist[21]

- Lee Holloway, co-founder of Cloudflare[22]

- Colleen Howe (1933–2009), sports agent and hockey team manager, known as "Mrs. Hockey"[23]

- Ralph Klein (1942–2013), former premier of Alberta, Canada

- Kevin Moore (1958–2013), English footballer[24]

- Ernie Moss (born 1949), English footballer[25]

- Nic Potter (1951–2013), British bassist for Van der Graaf Generator[26]

- Christina Ramberg (1946–1995), American painter associated with the Chicago Imagists[27]

- Pat Moran (1947-2011), British record producer, singer and Mellotron player with progressive rock band Spring

- David Rumelhart (1942–2011), American cognitive psychologist

- Colin Savage, father of footballer Robbie Savage[28]

- Sir Nicholas Wall (1945–2017), English judge[29]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Wang, LN; Zhu MW; Feng YQ; Wang JH. (2006). "Pick's disease with Pick bodies combined with progressive supranuclear palsy without tuft-shaped astrocytes: a clinical, neuroradiologic and pathological study of an autopsied case". Neuropathology 26 (3): 222–230. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00671.x. PMID 16771179.

- ↑ Semple, David. "Oxford Handbook of Psychiatry". Oxford Press. 2005. p.143

- ↑ American Academy of Neurology. "Dementia: Rare Brain Disorder Is Highly Hereditary". ScienceDaily, 4 November 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Pick disease

- ↑ Carlson, Neil R. Physiology of Behavior. Eleventh ed. 543. Print.

- ↑ Tacik P, DeTure M, Hinkle KM, Lin WL, Sanchez-Contreras M, Carlomagno Y, Pedraza O, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW (2015) A novel tau mutation in exon 12, p.Q336H, causes hereditary Pick disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol

- ↑ Kowalska A (2009) The genetics of dementias. Part 1: Molecular basis of frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17). Postepy Hig Med Dosw 63:278-286

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Yamakawa, K; Takanashi M; Watanabe M; Nakamura N; Kobayashi T; Hasegawa M; Mizuno Y; Tanaka S et al. (2006). "Pathological and biochemical studies on a case of Pick disease with severe white matter atrophy". Neuropathology 26 (6): 586–591. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.2006.00738.x. PMID 17203597.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Armstrong, RA; Cairns NJ, Lantos, PL (1998). "A comparison of histological and immunohistochemical methods for quantifying the pathological lesions of Pick's disease". Neuropathology 18 (4): 295–300. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1789.1998.tb00118.x.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Uchihara, T; Ikeda K; Tsuchiya K. (2003). "Pick body disease and Pick syndrome". Neuropathology 23 (4): 318–326. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00523.x. PMID 14719549.

- ↑ Iskei, E; Arai, H (2006). "Progress in the classification of non-Alzheimer-type degenerative dementias". Psychogeriactrics 6 (1): 41–42. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8301.2006.00166.x.

- ↑ Arai, T; Ikeda K; Akiyama H; Tsuchiya K; Iritani S; Ishiguro K; Yagishita S; Oda T et al. (2003). "Different immunoreactivities of the microtubule-binding region of tau and its molecular basis in brains from patients with Alzheimer's disease, Pick's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration". Acta Neuropathol. 105 (5): 489–498. doi:10.1007/s00401-003-0671-8. PMID 12677450.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Munoz, DG; Dickson DW; Bergeron C; Mackenzie IR; Delacourte A; Zhukareva V. (2003). "The neuropathology and biochemistry of frontotemporal dementia". Annals of Neurology. 54 supp. S5 (1): S24–S28. doi:10.1002/ana.10571. PMID 12833365.

- ↑ Zhukareva V1, Mann D, Pickering-Brown S, Uryu K, Shuck T, Shah K, Grossman M, Miller BL, Hulette CM, Feinstein SC, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (June 2002). "Sporadic Pick's disease: a tauopathy characterized by a spectrum of pathological tau isoforms in gray and white matter". Ann Neurol 51 (6): 730–9. doi:10.1002/ana.10222. PMID 12112079.

- ↑ Puig, B; Ferrer I; Ludueña RF; Avila J. (2005). "βII-tubulin and phospho-tau aggregates in Alzheimer's disease and Pick's disease". J. Alzheimer's Dis. 7 (1): 213–220. doi:10.3233/JAD-2005-7303. PMID 16006664.

- ↑ "Pick Disease". https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000744.htm.

- ↑ Kaufman, David Myland MD. Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists. 6th edition. 2007. Elsevier.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Amano, N; Iseki, E (1999). "Introduction: Pick's disease and frontotemporal dementia". Neuropathology 19 (1): 417–421. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1789.1999.00258.x.

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard. Don Cardwell, 72, Pitcher for 1969 Mets, Is Dead. The New York Times . January 16, 2008.

- ↑ "Sugarloaf frontman Jerry Corbetta dead at 68 – The Denver Post". 2016-09-20. http://www.denverpost.com/2016/09/20/colorado-hitmaker-jerry-corbetta-dead-at-68/.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E. (December 2003). "Robert W Floyd, In Memoriam". ACM SIGACT News 34 (4): 3–13. doi:10.1145/954092.954488. http://www-cs-faculty.stanford.edu/~uno/papers/floyd.ps.gz.

- ↑ Upson, Sandra. "The Devastating Decline of a Brilliant Young Coder". https://www.wired.com/story/lee-holloway-devastating-decline-brilliant-young-coder/. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ Sipple, George (March 6, 2009). "Fans mourn loss of "Mrs. Hockey," Colleen Howe". Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20151004110013/http://www.freep.com/article/20090306/SPORTS05/90306069?imw=Y. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ↑ Sportsteam. "Grimsby Town legend Kevin Moore passes away". Archived from the original on 2013-05-03. https://web.archive.org/web/20130503011757/http://www.thisisgrimsby.co.uk/Grimsby-Town-legend-Kevin-Moore-passes-away/story-18838049-detail/story.html#axzz2RsGaeCI7. Retrieved 2013-04-29.

- ↑ "Support for Valiants hero Ernie Moss after he is diagnosed with Pick's Disease". The Sentinel. 11 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20141102103942/http://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/Port-Vale-Support-Valiants-hero-Ernie-Moss/story-23091273-detail/story.html. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ Sally Potter (22 January 2013). "Nic Potter obituary | Music | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/jan/22/nic-potter. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Sexy, Proto-Feminist Art Of Christina Ramberg's Tragically Short Life". https://www.wbur.org/artery/2014/02/27/the-sexy-proto-feminist-art-of-christina-rambergs-tragically-short-life.

- ↑ Matt Roper (2011-04-26). "Robbie Savage's tears for his dad - and the end of his football career". mirror.co.uk. https://www.mirror.co.uk/celebs/news/2011/04/26/robbie-savage-s-tears-for-his-dad-and-the-end-of-his-football-career-115875-23086790/. Retrieved 2011-05-11.

- ↑ Gordon Rayner, "Sir Nicholas Wall, once Britain's top family law judge, commits suicide after dementia diagnosis", The Daily Telegraph, 23 February 2017.

Further reading

- Frontotemporal Dementia Information Page from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- Pick A. (1892) Über die Beziehungen der senilen Hirnatrophie zur Aphasie. Prager medicinische Wochenschrift Prague 17:165–167.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |