Physics:Optical lattice

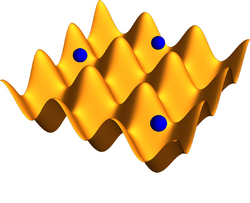

An optical lattice is formed by the interference of counter-propagating laser beams, creating a spatially periodic intensity pattern. The resulting periodic potential may trap neutral atoms via the Stark shift.[1] Atoms are cooled and congregate at the potential extrema (at maxima for blue-detuned lattices, and minima for red-detuned lattices). The resulting arrangement of trapped atoms resembles a crystal lattice[2] and can be used for quantum simulation.

Atoms trapped in the optical lattice may move due to quantum tunneling, even if the potential well depth of the lattice points exceeds the kinetic energy of the atoms, which is similar to the electrons in a conductor.[3] However, a superfluid–Mott insulator transition[4] may occur, if the interaction energy between the atoms becomes larger than the hopping energy when the well depth is very large. In the Mott insulator phase, atoms will be trapped in the potential minima and cannot move freely, which is similar to the electrons in an insulator. In the case of fermionic atoms, if the well depth is further increased the atoms are predicted to form an antiferromagnetic, i.e. Néel state at sufficiently low temperatures.[5]

History

Trapping atoms in standing waves of light was first proposed by V. S. Letokhov in 1968.[6]

Parameters

There are two important parameters of an optical lattice: the potential well depth and the periodicity.

Control of potential depth

The potential experienced by the atoms is related to the intensity of the laser used to generate the optical lattice. The potential depth of the optical lattice can be tuned in real time by changing the power of the laser, which is normally controlled by an acousto-optic modulator (AOM). The AOM is tuned to deflect a variable amount of the laser power into the optical lattice. Active power stabilization of the lattice laser can be accomplished by feedback of a photodiode signal to the AOM.

Control of periodicity

The periodicity of the optical lattice can be tuned by changing the wavelength of the laser or by changing the relative angle between the two laser beams. The real-time control of the periodicity of the lattice is still a challenging task. The wavelength of the laser cannot easily be varied over a large range in real time, and so the periodicity of the lattice is normally controlled by the relative angle between the laser beams.[7] However, it is difficult to keep the lattice stable while changing the relative angles, since the interference is sensitive to the relative phase between the laser beams. Titanium-sapphire lasers, with their large tunable range, provide a possible platform for direct tuning of wavelength in optical lattice systems.

Continuous control of the periodicity of a one-dimensional optical lattice while maintaining trapped atoms in-situ was first demonstrated in 2005 using a single-axis servo-controlled galvanometer.[8] This "accordion lattice" was able to vary the lattice periodicity from 1.30 to 9.3 μm. More recently, a different method of real-time control of the lattice periodicity was demonstrated,[9] in which the center fringe moved less than 2.7 μm while the lattice periodicity was changed from 0.96 to 11.2 μm. Keeping atoms (or other particles) trapped while changing the lattice periodicity remains to be tested more thoroughly experimentally. Such accordion lattices are useful for controlling ultracold atoms in optical lattices, where small spacing is essential for quantum tunneling, and large spacing enables single-site manipulation and spatially resolved detection. Site-resolved detection of the occupancy of lattice sites of both bosons and fermions within a high tunneling regime is regularly performed in quantum gas microscopes.[10][11]

Principle of operation

The trapping mechanism is via the Stark shift, where off-resonant light causes shifts to an atom's internal structure. The effect of the Stark shift is to create a potential proportional to the intensity. The effect of a light field on an atom is to induce an electric dipole moment as a result of the oscillating electric field. This induced dipole will then interact with the electric field, leading to an energy shift , where , where , is the dynamic polarizability of the atomic transition resonant at and is the detuning of the light field from resonance. In the case of ("red-detuning"), the induced dipole will be in phase with the field and thus the resulting potential energy gradient will point in the direction of higher intensity. This is the same trapping mechanism as in optical dipole traps (ODTs), with the only major difference being that the intensity of an optical lattice has a much more dramatic spatial variation than a standard ODT.[1]

A 1D optical lattice is formed by two counter-propagating laser beams of the same polarization. The beams will interfere, leading to a series of minima and maxima separated by , where is the wavelength of the light used to create the optical lattice. The resulting potential experienced by the atoms will be .

By use of additional laser beams, two- or three-dimensional optical lattices may be constructed. A 2D optical lattice may be constructed by interfering two orthogonal optical standing waves, giving rise to an array of 1D potential tubes. Likewise, three orthogonal optical standing waves can give rise to a 3D array of sites which may be approximated as tightly confining harmonic oscillator potentials.[2]

Technical challenges

The trapping potential experienced by atoms in an optical dipole trap is weak, generally below 1 mK. Thus atoms must be cooled significantly before loading them into the optical lattice. Cooling techniques used to this end include magneto-optical traps, Doppler cooling, polarization gradient cooling, Raman cooling, resolved sideband cooling, and evaporative cooling.[1]

If the periodic potential is to be added following condensation, as opposed to performing evaporative cooling in the lattice potential, it is necessary to consider the conditions for adiabatic loading of the lattice. The lattice must be slowly ramped up in intensity such that the condensate remains in its ground state in order to load the condensate into the ground band of the lattice. The timescale of the turn on will in general be set by the energy separation between the ground band and the first excited band.[2]

Once cold atoms are loaded into the optical lattice, they will experience heating by various mechanisms such as spontaneous scattering of photons from the optical lattice lasers. These mechanisms generally limit the lifetime of optical lattice experiments.[1]

Time of flight imaging

Once cooled and trapped in an optical lattice, the atoms can be manipulated or left to evolve. Common manipulations involve the "shaking" of the optical lattice by varying the relative phase between the counterpropagating beams or by modulating the frequency of one of the counterpropagating beams, or amplitude modulation of the lattice. After evolving in response to the lattice potential and any manipulations, the atoms can be imaged via absorption imaging.

A common observation technique is time of flight (TOF) imaging. TOF imaging works by first waiting some amount of time for the atoms to evolve in the lattice potential, then turning off the lattice potential. The atoms, now free, spread out at different rates according to their momenta. By controlling the amount of time the atoms are allowed to evolve, the distance travelled by atoms maps onto their momentum state when the lattice was turned off. Because the atoms in the lattice can only change in momentum by , a characteristic pattern in a TOF image of an optical-lattice system is a series of peaks along the lattice axis at momenta , where . Using TOF imaging, the momentum distribution of atoms in the lattice can be determined. Combined with in-situ absorption images (taken with the lattice still on), this is enough to determine the phase space density of the trapped atoms, an important metric for diagnosing Bose–Einstein condensation (or more generally, the formation of quantum degenerate phases of matter).

Uses

Quantum simulation

Atoms in an optical lattice provide an ideal quantum system where all parameters are highly controllable and where simplified models of condensed-matter physics may be experimentally realized. Because atoms can be imaged directly – something difficult to do with electrons in solids – they can be used to study effects that are difficult to observe in real crystals. Quantum gas microscopy techniques applied to trapped atom optical-lattice systems can even provide single-site imaging resolution of their evolution.[10]

By interfering differing numbers of beams in various geometries, varying lattice geometries can be created. These range from the simplest case of two counterpropagating beams forming a one-dimensional lattice, to more complex geometries like hexagonal lattices. The variety of geometries that can be produced in optical lattice systems allow the physical realization of different Hamiltonians, such as the Bose–Hubbard model,[4] the Kagome lattice and Sachdev–Ye–Kitaev model,[12] and the Aubry–André model. By studying the evolution of atoms under the influence of these Hamiltonians, which may be mapped to Hamiltonians describing the dynamics of electrons in various lattice models, insight about the solutions to the Hamiltonian can be gained. This is particularly relevant to complicated Hamiltonians which are not easily solvable using theoretical or numerical techniques, such as those for strongly correlated systems.

Optical clocks

The best atomic clocks in the world use atoms trapped in optical lattices, to obtain narrow spectral lines that are unaffected by the Doppler effect and recoil.[13][14]

Quantum information

They are also promising candidates for quantum information processing.[15][16]

Atom interferometry

Shaken optical lattices – where the phase of the lattice is modulated, causing the lattice pattern to scan back and forth – can be used to control the momentum state of the atoms trapped in the lattice. This control is exercised to split the atoms into populations of different momenta, propagate them to accumulate phase differences between the populations, and recombine them to produce an interference pattern.[17]

Other uses

Besides trapping cold atoms, optical lattices have been widely used in creating gratings and photonic crystals. They are also useful for sorting microscopic particles,[18] and may be useful for assembling cell arrays.

See also

- Neutral atom quantum computer

- Bose–Hubbard model

- Ultracold atom

- List of laser articles

- Electromagnetically induced grating

- Magic wavelength

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Grimm, Rudolf; Weidemüller, Matthias; Ovchinnikov, Yurii B. (2000), "Optical Dipole Traps for Neutral Atoms", Advances in Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics (Elsevier) 42: 95–170, doi:10.1016/s1049-250x(08)60186-x, ISBN 978-0-12-003842-8, Bibcode: 2000AAMOP..42...95G

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bloch, Immanuel (October 2005). "Ultracold quantum gases in optical lattices". Nature Physics 1 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1038/nphys138. Bibcode: 2005NatPh...1...23B.

- ↑ Gebhard, Florian (1997). The Mott metal-insulator transition models and methods. Berlin [etc.]: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-61481-4. https://archive.org/details/springer_10.1007-3-540-14858-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Greiner, Markus; Mandel, Olaf; Esslinger, Tilman; Hänsch, Theodor W.; Bloch, Immanuel (January 3, 2002). "Quantum phase transition from a superfluid to a Mott insulator in a gas of ultracold atoms". Nature 415 (6867): 39–44. doi:10.1038/415039a. PMID 11780110. Bibcode: 2002Natur.415...39G.

- ↑ Koetsier, Arnaud; Duine, R. A.; Bloch, Immanuel; Stoof, H. T. C. (2008). "Achieving the Néel state in an optical lattice". Phys. Rev. A 77 (2). doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.77.023623. Bibcode: 2008PhRvA..77b3623K.

- ↑ Letokhov, V.S. (May 1968). "Narrowing of the Doppler Width in a Standing Wave". Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 7: 272. Bibcode: 1968JETPL...7..272L. http://jetpletters.ru/ps/1685/article_25663.pdf.

- ↑ Fallani, Leonardo; Fort, Chiara; Lye, Jessica; Inguscio, Massimo (May 2005). "Bose-Einstein condensate in an optical lattice with tunable spacing: transport and static properties". Optics Express 13 (11): 4303–4313. doi:10.1364/OPEX.13.004303. PMID 19495345. Bibcode: 2005OExpr..13.4303F.

- ↑ Huckans, J. H. (December 2006). "Optical Lattices and Quantum Degenerate Rb-87 in Reduced Dimensions". University of Maryland Doctoral Dissertation.

- ↑ Li, T. C.; Kelkar, H.; Medellin, D.; Raizen, M. G. (April 3, 2008). "Real-time control of the periodicity of a standing wave: an optical accordion". Optics Express 16 (8): 5465–5470. doi:10.1364/OE.16.005465. PMID 18542649. Bibcode: 2008OExpr..16.5465L.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bakr, Waseem S.; Gillen, Jonathon I.; Peng, Amy; Fölling, Simon; Greiner, Markus (2009-11-05). "A quantum gas microscope for detecting single atoms in a Hubbard-regime optical lattice" (in en). Nature 462 (7269): 74–77. doi:10.1038/nature08482. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19890326. Bibcode: 2009Natur.462...74B.

- ↑ Haller, Elmar; Hudson, James; Kelly, Andrew; Cotta, Dylan A.; Peaudecerf, Bruno; Bruce, Graham D.; Kuhr, Stefan (2015-09-01). "Single-atom imaging of fermions in a quantum-gas microscope" (in en). Nature Physics 11 (9): 738–742. doi:10.1038/nphys3403. ISSN 1745-2473. Bibcode: 2015NatPh..11..738H.

- ↑ Wei, Chenan; Sedrakyan, Tigran (2021-01-29). "Optical lattice platform for the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model". Phys. Rev. A 103 (1). doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.103.013323. Bibcode: 2021PhRvA.103a3323W.

- ↑ Derevianko, Andrei; Katori, Hidetoshi (3 May 2011). "Colloquium: Physics of optical lattice clocks". Reviews of Modern Physics 83 (2): 331–347. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.331. Bibcode: 2011RvMP...83..331D.

- ↑ "Ye lab". http://jila.colorado.edu/yelabs/research/ultracold-strontium.

- ↑ Brennen, Gavin K.; Caves, Carlton; Jessen, Poul S.; Deutsch, Ivan H. (1999). "Quantum logic gates in optical lattices". Phys. Rev. Lett. 82 (5): 1060–1063. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.1060. Bibcode: 1999PhRvL..82.1060B.

- ↑ Yang, Bing; Sun, Hui; Hunag, Chun-Jiong; Wang, Han-Yi; Deng, Youjin; Dai, Han-Ning; Yuan, Zhen-Sheng; Pan, Jian-Wei (2020). "Cooling and entangling ultracold atoms in optical lattices". Science 369 (6503): 550–553. doi:10.1126/science.aaz6801. PMID 32554628. Bibcode: 2020Sci...369..550Y.

- ↑ Weidner, C. A.; Anderson, Dana Z. (27 June 2018). "Experimental Demonstration of Shaken-Lattice Interferometry". Physical Review Letters 120 (26). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.263201. PMID 30004774. Bibcode: 2018PhRvL.120z3201W.

- ↑ MacDonald, M. P.; Spalding, G. C.; Dholakia, K. (November 27, 2003). "Microfluidic sorting in an optical lattice". Nature 426 (6965): 421–424. doi:10.1038/nature02144. PMID 14647376. Bibcode: 2003Natur.426..421M.

External links

|