Medicine:Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome

| Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hemorrhagic adrenalitis |

| |

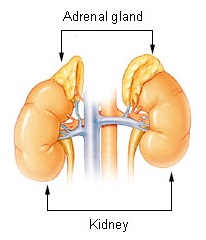

| The adrenal glands lie above the kidneys | |

| Causes | Bacterial infection |

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) is defined as adrenal gland failure due to bleeding into the adrenal glands, commonly caused by severe bacterial infection. Typically, it is caused by Neisseria meningitidis.[1]

The bacterial infection leads to massive bleeding into one or (usually) both adrenal glands.[2] It is characterized by overwhelming bacterial infection meningococcemia leading to massive blood invasion, organ failure, coma, low blood pressure and shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with widespread purpura, rapidly developing adrenocortical insufficiency and death.

Signs and symptoms

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome can be caused by a number of different organisms (see below). When caused by Neisseria meningitidis, WFS is considered the most severe form of meningococcal sepsis. The onset of the illness is nonspecific with fever, rigors, vomiting, and headache. Soon a rash appears; first macular, not much different from the rose spots of typhoid, and rapidly becoming petechial and purpuric with a dusky gray color. Low blood pressure (hypotension) develops and rapidly leads to septic shock. The cyanosis of extremities can be extreme and the patient is very prostrated or comatose. In this form of meningococcal disease, meningitis generally does not occur. Low levels of blood glucose and sodium, high levels of potassium in the blood, and the ACTH stimulation test demonstrate the acute adrenal failure. Leukocytosis need not be extreme and in fact leukopenia may be seen and it is a very poor prognostic sign. C-reactive protein levels can be elevated or almost normal. Thrombocytopenia is sometimes extreme, with alteration in prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) suggestive of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Acidosis and acute kidney failure can be seen as in any severe sepsis. Meningococci can be readily cultured from blood or cerebrospinal fluid, and can sometimes be seen in smears of cutaneous lesions. Difficulty swallowing, atrophy of the tongue, and cracks at the corners of the mouth are also characteristic features.[citation needed]

Causes

Multiple species of bacteria can be associated with the condition:

- Meningococcus is another term for the bacterial species Neisseria meningitidis; blood infection with said species usually underlies WFS. While many infectious agents can infect the adrenals, an acute, selective infection is usually meningococcus.[citation needed]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa can also cause WFS.[3]

- WFS can also be caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae infections, a common bacterial pathogen typically associated with meningitis in the adult and elderly population.[2]

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis could also cause WFS. Tubercular invasion of the adrenal glands could cause hemorrhagic destruction of the glands and cause mineralocorticoid deficiency[citation needed].

- Staphylococcus aureus has recently also been implicated in pediatric WFS.[4]

- It can also be associated with Haemophilus influenzae.[5][6]

- Adrenal hemorrhage characteristic of the Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome has been identified in several autopsies of patients who died of sepsis secondary to capnocytophaga canimorsus infection. [7]

Viruses may also be implicated in adrenal problems:

- Cytomegalovirus can cause adrenal insufficiency,[8] especially in the immunocompromised.

- Ebola virus infection may also cause similar acute adrenal failure.[9]

Diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria are based on clinical features of adrenal insufficiency as well as identifying the causal agent. If the causal agent is suspected to be meningitis a lumbar puncture is performed. If the causal agent is suspected to be bacterial a blood culture and complete blood count is performed. An adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation test can be performed to assess adrenal function.

Prevention

Routine vaccination against meningococcus is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for all 11- to 18-year-olds and people who have poor splenic function (who, for example, have had their spleen removed or who have sickle-cell disease which damages the spleen), or who have certain immune disorders, such as a complement deficiency.[10]

Treatment

Fulminant infection from meningococcal bacteria in the bloodstream is a medical emergency and requires emergent treatment with vasopressors, fluid resuscitation, and appropriate antibiotics. Benzylpenicillin was once the drug of choice with chloramphenicol as a good alternative in allergic patients. Ceftriaxone is an antibiotic commonly employed today. Hydrocortisone can sometimes reverse the adrenal insufficiency. Amputations, reconstructive surgery, and tissue grafting are sometimes needed as a result of tissue necrosis (typically of the extremities) caused by the infection.[citation needed]

Prognosis

The prognosis of Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome varies by severity of the illness. Around 15% of patients with significant acute bilateral adrenal bleeding experience a fatal outcome. In cases where diagnosis and appropriate treatment are delayed, the case fatality rate approaches 50%. Recovery is possible with appropriate, timely management of the illness. Mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid treatments may be necessary depending on the recovering patient's electrolyte status and response to treatment. Research shows that people with adrenal hemorrhage can regain adrenal function to some degree.[11]

History

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome is named after Rupert Waterhouse (1873–1958), an English physician, and Carl Friderichsen (1886–1979), a Danish pediatrician, who wrote papers on the syndrome, which had been previously described.[12][13]

References

- ↑ "Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). http://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/GARD/Disease.aspx?PageID=4&diseaseID=9449.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Robins and Coltran: Pathological Basis of Disease (7th ed.). Elsevier. 2005. pp. 1214–5. ISBN 978-0-7216-0187-8.

- ↑ "Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000609.htm.

- ↑ "Staphylococcus aureus sepsis and the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome in children". N Engl J Med 353 (12): 1245–51. 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044194. PMID 16177250.

- ↑ "Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome without purpura due to Haemophilus influenzae group B". Postgrad Med J 61 (711): 67–8. January 1985. doi:10.1136/pgmj.61.711.67. PMID 3873065.

- ↑ "Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in an immunocompetent young adult". South. Med. J. 82 (12): 1571–3. December 1989. doi:10.1097/00007611-198912000-00029. PMID 2595428.

- ↑ Butler, T. (July 2015). "Capnocytophaga canimorsus: an emerging cause of sepsis, meningitis, and post-splenectomy infection after dog bites". pp. 1271–1280. doi:10.1007/s10096-015-2360-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25828064/#:~:text=Newly%20named%20in%201989%2C%20Capnocytophaga,humans%20principally%20by%20dog%20bites..

- ↑ Uno, Kenji; Konishi, Mitsuru; Yoshimoto, Eiichiro; Kasahara, Kei; Mori, Kei; Maeda, Koichi; Ishida, Eiwa; Konishi, Noboru et al. (1 January 2007). "Fatal Cytomegalovirus-Associated Adrenal Insufficiency in an AIDS Patient Receiving Corticosteroid Therapy". Internal Medicine 46 (9): 617–620. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.46.1886. PMID 17473501.

- ↑ "BMJ Ebola fact-sheet". https://www.bmj.com/bmj/section-pdf/816196%3Fpath%3D/bmj/349/7987/Clinical_Review.full.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjW2PqcmpH2AhXDoFwKHQIoDt0QFnoECDMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3I2juSAXxiuZs9VPRX1DSZ.

- ↑ "Deficiency of the eighth component of complement associated with recurrent meningococcal meningitis--case report and literature review". Braz J Infect Dis 8 (4): 328–30. 2004. doi:10.1590/S1413-86702004000400010. PMID 15565265. http://www.lume.ufrgs.br/bitstream/10183/81786/1/000826494.pdf.

- ↑ Karki, Bhesh R.; Sedhai, Yub Raj; Bokhari, Syed Rizwan A. (2022). "Waterhouse-Friderichsen Syndrome". StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551510/.

- ↑ Waterhouse R (1911). "A case of suprarenal apoplexy". Lancet 1 (4566): 577–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)60988-7.

- ↑ Friderichsen C (1918). "Nebennierenapoplexie bei kleinen Kindern". Jahrbuch für Kinderheilkunde und Physische Erziehung 87: 109–25.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |