Medicine:Q fever

| Q fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Query fever, coxiellosis[1][2] |

| |

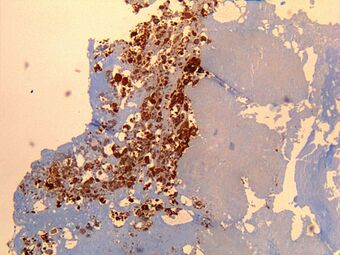

| Immunohistochemical detection of C. burnetii in resected cardiac valve of a 60-year-old man with Q fever endocarditis, Cayenne, French Guiana: Monoclonal antibodies against C. burnetii and hematoxylin were used for staining; original magnification is ×50. | |

| Types | acute, chronic[1] |

| Risk factors | Contact with livestock[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | pneumonia, influenza, brucellosis, leptospirosis, meningitis, viral hepatitis, dengue fever, malaria, other rickettsial infections[2] |

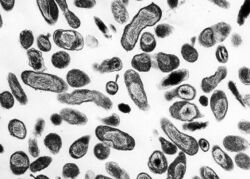

Q fever or query fever is a disease caused by infection with Coxiella burnetii,[1][3][4] a bacterium that affects humans and other animals. This organism is uncommon, but may be found in cattle, sheep, goats, and other domestic mammals, including cats and dogs. The infection results from inhalation of a spore-like small-cell variant, and from contact with the milk, urine, feces, vaginal mucus, or semen of infected animals. Rarely, the disease is tick-borne.[5] The incubation period can range from 9 to 40 days. Humans are vulnerable to Q fever, and infection can result from even a few organisms.[5] The bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogenic parasite.

Signs and symptoms

The incubation period is usually two to three weeks.[6] The most common manifestation is flu-like symptoms: abrupt onset of fever, malaise, profuse perspiration, severe headache, muscle pain, joint pain, loss of appetite, upper respiratory problems, dry cough, pleuritic pain, chills, confusion, and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. About half of infected individuals exhibit no symptoms.[6]

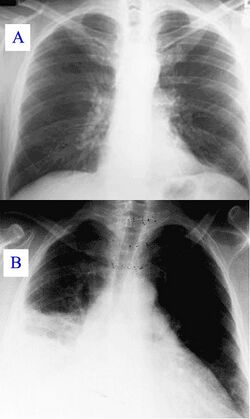

During its course, the disease can progress to an atypical pneumonia, which can result in a life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome, usually occurring during the first four to five days of infection.[7]

Less often, Q fever causes (granulomatous) hepatitis, which may be asymptomatic or become symptomatic with malaise, fever, liver enlargement, and pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. This hepatitis often results in the elevation of transaminase values, although jaundice is uncommon. Q fever can also rarely result in retinal vasculitis.[8]

The chronic form of Q fever is virtually identical to endocarditis (i.e. inflammation of the inner lining of the heart),[9] which can occur months or decades following the infection. It is usually fatal if untreated. However, with appropriate treatment, the mortality falls to around 10%. A minority of Q fever survivors develop Q fever fatigue syndrome after acute infection, one of the more well-studied post-acute infection syndromes. Q fever fatigue syndrome is characterised by post-exertional malaise and debilitating fatigue. People with Q fever fatigue syndrome frequently meet the diagnostic criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Symptoms often persist years after the initial infection.[10]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on serology[11][12] (looking for an antibody response) rather than looking for the organism itself. Serology allows the detection of chronic infection by the appearance of high levels of the antibody against the virulent form of the bacterium. Molecular detection of bacterial DNA is increasingly used. Contrary to most obligate intracellular parasites, Coxiella burnetii can be grown in an axenic culture, but its culture is technically difficult and not routinely available in most microbiology laboratories.[13]

Q fever can cause infective endocarditis (infection of the heart valves), which may require transoesophageal echocardiography to diagnose. Q fever hepatitis manifests as an elevation of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase, but a definitive diagnosis is only possible on liver biopsy, which shows the characteristic fibrin ring granulomas.[14]

Prevention

Research done in the 1960s–1970s by French Canadian-American microbiologist and virologist Paul Fiset was instrumental in the development of the first successful Q fever vaccine.[15]

Protection is offered by Q-Vax, a whole-cell, inactivated vaccine developed by an Australian vaccine manufacturing company, CSL Limited.[16] The intradermal vaccination is composed of killed C. burnetii organisms. Skin and blood tests should be done before vaccination to identify pre-existing immunity because vaccinating people who already have immunity can result in a severe local reaction. After a single dose of vaccine, protective immunity lasts for many years. Revaccination is not generally required. Annual screening is typically recommended.[17]

In 2001, Australia introduced a national Q fever vaccination program for people working in "at-risk" occupations. Vaccinated or previously exposed people may have their status recorded on the Australian Q Fever Register,[18] which may be a condition of employment in the meat processing industry or in veterinary research.[19] An earlier killed vaccine had been developed in the Soviet Union, but its side effects prevented its licensing abroad. Preliminary results suggest vaccination of animals may be a method of control. Published trials proved that use of a registered phase vaccine (Coxevac) on infected farms is a tool of major interest to manage or prevent early or late abortion, repeat breeding, anoestrus, silent oestrus, metritis, and decreases in milk yield when C. burnetii is the major cause of these problems.[20][21]

Q fever is primarily transmitted to humans through inhalation of aerosols contaminated with Coxiella burnetii from infected animals, notably cattle, sheep, and goats. Occupational groups such as farmers, veterinarians, and abattoir workers are at heightened risk. Preventive strategies include:[22]

- Vaccination: In countries like Australia, where Q fever is endemic, vaccination programs targeting high-risk populations have been implemented. The vaccine has proven effective in reducing the incidence of the disease among these groups. CDC

- Hygiene Measures: Implementing strict biosecurity and hygiene practices in livestock handling facilities can minimize environmental contamination. This includes proper disposal of animal waste and birthing products, which are known to harbor high concentrations of bacteria.

- Public Awareness: Educating at-risk populations about Q fever transmission, symptoms, and preventive measures is crucial. Awareness campaigns can lead to early diagnosis and treatment, thereby reducing complications associated with the disease.

Treatment

Treatment of acute Q fever with antibiotics is very effective.[7] Commonly used antibiotics include doxycycline, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin; the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine is also used.[7] Chronic Q fever is more difficult to treat and can require up to four years of treatment with doxycycline and quinolones or doxycycline with hydroxychloroquine.[7] If a person has chronic Q fever, doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine will be prescribed for at least 18 months. Q fever in pregnancy is especially difficult to treat because doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are contraindicated in pregnancy. The preferred treatment for pregnancy and children under the age of eight is co-trimoxazole.[23][24]

Epidemiology

Q fever is a globally distributed zoonotic disease caused by a highly sustainable and virulent bacterium. The pathogenic agent is found worldwide, except New Zealand[25] and Antarctica.[26] Understanding the transmission and risk factors of Q fever is crucial for public health due to its potential to cause widespread infection.

Recent data indicate that Q fever remains a significant public health concern worldwide. In 2019, the United States reported 178 acute Q fever cases and 34 chronic cases. Notably, in 2024, the state of Victoria, Australia, experienced a marked increase in Q fever cases, with 77 reported instances—a significant rise compared to the previous five years. This surge prompted health authorities to issue alerts emphasizing the importance of preventive measures and awareness.[27]

Transmission and occupational risks

Transmission primarily occurs through the inhalation of contaminated dust, contact with contaminated milk, meat, or wool, and particularly birthing products. Ticks can transfer the pathogenic agent to other animals. While human-to-human transmission is rare, often associated with the transmission of birth products, sexual contact, and blood transfusion,[26] certain occupations pose higher risks for Q fever:[28]

- Veterinary personnel

- Stockyard workers

- Farmers

- Sheep shearers

- Animal transporters

- Laboratory workers handling potentially infected veterinary samples or visiting abattoirs

- People who cull and process kangaroos

- Hide (tannery) workers

It is important to note that anyone who has contact with animals infected with Q fever bacteria, especially people who work on farms or with animals, is at an increased risk of contracting the disease.[29] Understanding these occupational risks is crucial for public health.

Prevalence and risk factors

Studies indicate a higher prevalence of Q fever in men than in women,[30][31] potentially linked to occupational exposure rates.[32] Other contributing risk factors include geography, age, and occupational exposure. Diagnosis relies on blood compatibility testing, with treatment varying for acute and chronic cases. Acute disease often responds to doxycycline, while chronic cases may require a combination of doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine.[33] It is worth noting that Q fever was officially reported in the United States as a notifiable disease in 1999 due to its potential biowarfare agent status.[34]

Q fever exhibits global epidemiological patterns, with higher incidence rates reported in certain countries. In Africa, wild animals in rainforests primarily transmit the disease, making it endemic.[26] Unique patterns are observed in Latin America, but reporting is sporadic and inconsistent between and among countries, making it difficult to track and address.[35]

Recent outbreaks in European countries, including the Netherlands and France, have been linked to urbanized goat farming, raising concerns about the safety of intensive livestock farming practices and the potential risks of zoonotic diseases. Similarly, in the United States, Q fever is more common in livestock farming regions, especially in the West and the Great Plains. California, Texas, and Iowa account for almost 40% of reported cases, with a higher incidence during the spring and early summer when livestock are breeding, regardless of whether the infection is acute or chronic.[29]

These outbreaks have affected a significant number of people, with immunocompromised individuals being more severely impacted.[34] The global nature of Q fever and its association with livestock farming highlight the importance of implementing measures to prevent and control the spread of the disease, particularly in high-risk regions.

Age and occupational exposure

Older men in the West and Great Plains regions, involved in close contact with livestock management, are at a higher risk of contracting chronic Q fever.[32] This risk may be further increased for those with a history of cardiac problems.[32] The disease can manifest years after the initial infection, presenting symptoms such as non-specific fatigue, fever, weight loss, and endocarditis.[26][32] Additionally, certain populations are more vulnerable to Q fever, including children living in farming communities, who may experience similar symptoms as adults.[36] There have also been reported cases of Q fever among United States military service members,[37] particularly those deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan, which further highlights the importance of understanding and addressing the occupational risks associated with Q fever.[38]

Prevention and public health education

Proper public health education is crucial in reducing the number of Q fever cases. Raising awareness about transmission routes, occupational risks, and preventive measures[34] can help prevent the spread of disease.[39]

Interdisciplinary collaboration between medical personnel and farmers is critical when developing strategies for control and prevention in a community.[40] Awareness campaigns should particularly target occupations that work with livestock, focusing on risk-reduction procedures such as herd monitoring, implementing sanitation practices and personal protective equipment, and vaccinating animals.[40] Locating livestock farms at least 500 meters away from residential areas can also help reduce animal-to-human transmission.[40]

History

Q fever was first described in 1935 by Edward Holbrook Derrick[41] in slaughterhouse workers in Brisbane, Queensland. The "Q" stands for "query" and was applied at a time when the causative agent was unknown; it was chosen over suggestions of abattoir fever and Queensland rickettsial fever, to avoid directing negative connotations at either the cattle industry or the state of Queensland.[42]

The pathogen of Q fever was discovered in 1937, when Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Mavis Freeman isolated the bacterium from one of Derrick's patients.[43] It was originally identified as a species of Rickettsia. H.R. Cox and Gordon Davis elucidated the transmission when they isolated it from ticks found in the US state of Montana in 1938.[44] It is a zoonotic disease whose most common animal reservoirs are cattle, sheep, and goats. Coxiella burnetii – named for Cox and Burnet – is no longer regarded as closely related to the Rickettsiae, but as similar to Legionella and Francisella, and is a Gammaproteobacterium.

Society and culture

An early mention of Q fever was important in one of the early Dr. Kildare films (1939, Calling Dr. Kildare). Kildare's mentor Dr. Gillespie (Lionel Barrymore) tires of his protégé working fruitlessly on "exotic diagnoses" ("I think it's Q fever!") and sends him to work in a neighborhood clinic, instead.[45][46]

Biological warfare

C. burnetii has been used to develop biological weapons.[47]

The United States investigated it as a potential biological warfare agent in the 1950s, with eventual standardization as agent OU. At Fort Detrick and Dugway Proving Ground, human trials were conducted on Whitecoat volunteers to determine the median infective dose (18 MICLD50/person i.h.) and course of infection. The Deseret Test Center dispensed biological Agent OU with ships and aircraft, during Project 112 and Project SHAD.[48] As a standardized biological, it was manufactured in large quantities at Pine Bluff Arsenal, with 5,098 gallons in the arsenal in bulk at the time of demilitarization in 1970. C. burnetii is currently ranked as a "category B" bioterrorism agent by the CDC.[49] It can be contagious and is very stable in aerosols in a wide range of temperatures. Q fever microorganisms may survive on surfaces for up to 60 days. It is considered a good agent in part because its ID50 (number of bacilli needed to infect 50% of individuals) is considered to be one, making it the lowest known.[50]

In animals

Q fever can affect many species of domestic and wild animals, including ruminants (cattle, sheep, goats, bison,[51] deer species[52][53]...), carnivores (dogs, cats,[54] seals[55]...), rodents,[56] reptiles and birds. However, ruminants (cattle, goats, and sheep) are the most frequently affected animals and can serve as a reservoir for the bacteria.[57]

Clinical signs

In contrast to humans, though a respiratory and cardiac infection could be experimentally reproduced in cattle,[58] the clinical signs mainly affect the reproductive system. Q fever in ruminants is, therefore, mainly responsible for abortions, metritis, retained placenta, and infertility.

The clinical signs vary between species. In small ruminants (sheep and goats), it is dominated by abortions, premature births, stillbirths, and the birth of weak lambs or kids. One of the characteristics of abortions in goats is that they are very frequent and clustered in the first year or two after contamination of the farm. This is known as an abortion storm.[59]

In cattle, although abortions also occur, they are less frequent and more sporadic. The clinical picture is rather dominated by nonspecific signs such as placental retentions, metritis, and consequent fertility disorders.[60][61][62]

Epidemiology

Except for New Zealand, which is currently free of Q fever, the disease is present globally. Numerous epidemiological surveys have been carried out. They have shown that about one in three cattle farms and one in four sheep or goat farms are infected,[63] but wide variations are seen between studies and countries. In China, Iran, Great Britain, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Spain, the US, Belgium, Denmark, Croatia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Serbia, Slovenia, and Jordan, for example, more than 50% of cattle herds were infected with Q fever.[64][65][66][67][68][69][70]

Infected animals shed the bacteria by three routes - genital discharge, faeces, and milk.[71] Excretion is greatest at the time of parturition or abortion, and placentas and aborted fetuses are the main sources of bacteria, particularly in goats.

As C. burnetii is small and resistant in the environment, it is easily airborne and can be transmitted from one farm to another, even if several kilometres away.[72]

Control

Biosecurity measures

Based on the epidemiological data, biosecurity measures can be derived:[73]

- The spread of manure from infected farms should be avoided in windy conditions

- The level of hygiene must be very high during parturition and fetal annexes, and fetuses must be collected and destroyed as soon as possible

Medical measures

A vaccine for cattle, goats, and sheep exists. It reduces clinical expression, such as abortions, and decreases the excretion of the bacteria by the animals, leading to control of Q fever in herds.[74]

Vaccination of herds against Q fever has been shown to reduce the risk of human infection.[75]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Epidemiology and Statistics | Q Fever | CDC" (in en-us). 2019-09-16. https://www.cdc.gov/qfever/stats/index.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 ((National Organization for Rare Disorders)) (2003). "Q Fever" (in en). NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-7817-3063-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=99YPDvFWBB0C&pg=PA293.

- ↑ "Genetic diversity of the Q fever agent, Coxiella burnetii, assessed by microarray-based whole-genome comparisons". Journal of Bacteriology 188 (7): 2309–2324. April 2006. doi:10.1128/JB.188.7.2309-2324.2006. PMID 16547017.

- ↑ "Q fever | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program" (in en-US). https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7515/q-fever.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Q Fever | CDC" (in en-us). 2017-12-27. https://www.cdc.gov/qfever/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Q Fever". CDC Health Information for International Travel: The Yellow Book. Oxford University Press. 2011. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-19-976901-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=5vCQpr1WTS8C&pg=PA270.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Coxiella/Q Fever". https://www.lecturio.com/concepts/coxiella-q-fever/.

- ↑ "[Is A29, B12 vasculitis caused by the Q fever agent? (Coxiella burnetii)]" (in fr). Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie 15 (5): 315–321. 1992. OCLC 116712679. PMID 1430809.

- ↑ "Chronic Q fever in the United States". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 44 (6): 2283–2287. June 2006. doi:10.1128/JCM.02365-05. PMID 16757641.

- ↑ "Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes". Nature Medicine 28 (5): 911–923. May 2022. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01810-6. PMID 35585196.

- ↑ "Q fever". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 12 (4): 518–553. October 1999. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.4.518. PMID 10515901.

- ↑ "Current laboratory diagnosis of Q fever". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 13 (4): 257–262. October 2002. doi:10.1053/spid.2002.127199. PMID 12491231.

- ↑ "Host cell-free growth of the Q fever bacterium Coxiella burnetii". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (11): 4430–4434. March 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812074106. PMID 19246385. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.4430O.

- ↑ "Patient with fever and diarrhea". Clinical Infectious Diseases 42 (7): 1051–2. May 2006. doi:10.1086/501027.

- ↑ "Dr. Paul Fiset, 78, Microbiologist And Developer of Q Fever Vaccine". The New York Times: p. C-17. March 8, 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/03/08/us/dr-paul-fiset-78-microbiologist-and-developer-of-q-fever-vaccine.html.

- ↑ "Q fever Vaccine". 17 January 2014. http://www.csl.com.au/docs/39/836/Q-Vax_PI_V4_TGA-Approved-17%20January%202014.pdf.

- ↑ "USCF communicable disease prevention program animal exposure surveillance program". http://cdp.ucsf.edu/fileUpload/UCSF_CDP_Q_Fever_Surveillance_Policy_Q_Neg_Wethers.pdf.

- ↑ "Australian Q Fever Register". AusVet. https://www.qfever.org.

- ↑ "Q-Fever Vaccinations" (in en). 2019-11-20. https://fvas.unimelb.edu.au/students/general/q-fever.

- ↑ "Q Fever (Coxiella burnetii) Eradication in a Dairy Herd by Using Vaccination with a Phase 1 Vaccine". XXV World Buiatrics Congress. Budapest. 2008.

- ↑ "Reduction of Coxiella burnetii prevalence by vaccination of goats and sheep, The Netherlands". Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (3): 379–386. March 2011. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101157. PMID 21392427.

- ↑ CDC (2025-03-05). "Clinical Guidance for Q fever" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/q-fever/hcp/clinical-guidance/index.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- ↑ "Managing Q fever during pregnancy: the benefits of long-term cotrimoxazole therapy". Clinical Infectious Diseases 45 (5): 548–555. September 2007. doi:10.1086/520661. PMID 17682987.

- ↑ "Query Fever - MARI REF" (in en-US). 20 July 2021. https://mariref.com/query-fever-professional/.

- ↑ "Q fever". The Journal of Infection 54 (4): 313–318. April 2007. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.10.048. PMID 17147957.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Salifu, Samson Pandam; Bukari, Abdul-Rahman Adamu; Frangoulidis, Dimitrios; Wheelhouse, Nick (2019-05-01). "Current perspectives on the transmission of Q fever: Highlighting the need for a systematic molecular approach for a neglected disease in Africa". Acta Tropica 193: 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.02.032. ISSN 0001-706X. PMID 30831112. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001706X19300889.

- ↑ CDC (2024-05-20). "Epidemiology and Statistics" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/q-fever/data-research/index.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- ↑ "Q fever: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia" (in en). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000611.htm.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 CDC (2021-08-06). "Q fever epidemiology and statistics | CDC" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/qfever/stats/index.html.

- ↑ "Acute Q fever in adult patients: report on 63 sporadic cases in an urban area". Clinical Infectious Diseases 29 (4): 874–879. October 1999. doi:10.1086/520452. PMID 10589906.

- ↑ "An important outbreak of human Q fever in a Swiss Alpine valley". International Journal of Epidemiology 16 (2): 282–287. June 1987. doi:10.1093/ije/16.2.282. PMID 3301708.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 "Epidemiology and Statistics | Q Fever | CDC" (in en-us). 2019-09-16. https://www.cdc.gov/qfever/stats/index.html.

- ↑ Hartzell, Joshua D.; Wood-Morris, Robert N.; Martinez, Luis J.; Trotta, Richard F. (May 2008). "Q Fever: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 83 (5): 574–579. doi:10.4065/83.5.574. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 18452690.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Patil, Sachin M.; Regunath, Hariharan (2023), "Q Fever", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 32310555, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556095/, retrieved 2023-11-21

- ↑ Fernandes, Jorlan; Sampaio de Lemos, Elba Regina (2023-04-01). "The multifaceted Q fever epidemiology: a call to implement One Health approach in Latin America". The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 20. doi:10.1016/j.lana.2023.100463. ISSN 2667-193X. PMID 36915670.

- ↑ Bwatota, Shedrack Festo; Cook, Elizabeth Anne Jessie; de Clare Bronsvoort, Barend Mark; Wheelhouse, Nick; Hernandez-Castor, Luis E; Shirima, Gabriel Mkilema (2022-11-17). "Epidemiology of Q-fever in domestic ruminants and humans in Africa. A systematic review" (in en). CABI One Health. doi:10.1079/cabionehealth.2022.0008. ISSN 2791-223X.

- ↑ Anderson, Alicia D.; Smoak, Bonnie; Shuping, Eric; Ockenhouse, Christopher; Petruccelli, Bruno (2005). "Q Fever and the US Military - Volume 11, Number 8—August 2005 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC" (in en-us). Emerging Infectious Diseases 11 (8): 1320–1322. doi:10.3201/eid1108.050314. PMID 16110586. PMC 3320491. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/11/8/05-0314_article.

- ↑ Hartzell, Joshua (May 2008). "Q Fever: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Concise Review for Physicians 83 (5): 574–579. doi:10.4065/83.5.574. PMID 18452690.

- ↑ ((CDC)) (2019-01-15). "Prevention of Q fever | CDC" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/qfever/prevention/index.html.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Ullah, Qudrat; Jamil, Tariq; Saqib, Muhammad; Iqbal, Mudassar; Neubauer, Heinrich (2022-07-28). "Q Fever—A Neglected Zoonosis". Microorganisms 10 (8): 1530. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10081530. ISSN 2076-2607. PMID 36013948.

- ↑ "'Q' Fever a new fever entity: clinical features. diagnosis, and laboratory investigation". Medical Journal of Australia 2 (8): 281–299. August 1937. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1937.tb43743.x. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1937.tb43743.x.

- ↑ "Historical aspects of Q Fever" (in en). Q Fever: The Disease. I. CRC Press. 1990. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8493-5984-2.

- ↑ "Experimental studies on the virus of "Q" fever". Reviews of Infectious Diseases 5 (4): 800–808. 1 July 1983. doi:10.1093/clinids/5.4.800. PMID 6194551.

- ↑ "Public Health Weekly Reports for DECEMBER 30, 1938". Public Health Reports 53 (52): 2259–2309. December 1938. doi:10.2307/4582746. PMID 19315693.

- ↑ "Calling Dr. Kildare". Movie Mirrors Index. http://www.san.beck.org/MM/1939/CallingDrKildare.html.

- ↑ "When Americans called for Dr. Kildare: images of physicians and nurses in the Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespie movies, 1937-1947". Medical Heritage 1 (5): 348–363. September 1985. PMID 11616027. http://www.truthaboutnursing.org/images/kalisch/when_americans_called_dr_kildare.pdf.

- ↑ "Q fever: a biological weapon in your backyard". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases 3 (11): 709–721. November 2003. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00804-1. PMID 14592601.

- ↑ "Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD, Shady Grove revised fact sheet". https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Fact-Sheets/2003/12/02/Shady-Grove-Revised.

- ↑ "Complete genome sequence of the Q-fever pathogen Coxiella burnetii". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (9): 5455–5460. April 2003. doi:10.1073/pnas.0931379100. PMID 12704232. Bibcode: 2003PNAS..100.5455S.

- ↑ Brooke, Russell John; Kretzschmar, Mirjam E. E.; Mutters, Nico T.; Teunis, Peter F. (21 October 2013). "Human dose response relation for airborne exposure to Coxiella burnetii". BMC Infectious Diseases 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-488. ISSN 1471-2334. PMID 24138807.

- ↑ "Pathogens with potential impact on reproduction in captive and free-ranging European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland - a serological survey". BMC Veterinary Research 17 (1). November 2021. doi:10.1186/s12917-021-03057-8. PMID 34736464.

- ↑ "Coxiella burnetii infection in roe deer during Q fever epidemic, the Netherlands". Emerging Infectious Diseases 17 (12): 2369–2371. December 2011. doi:10.3201/eid1712.110580. PMID 22172398.

- ↑ "Seroepidemiology of Coxiella burnetii in wild white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in New York, United States". Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 12 (11): 942–947. November 2012. doi:10.1089/vbz.2011.0952. PMID 22989183.

- ↑ "Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii seropositivity and shedding in farm, pet and feral cats and associated risk factors in farm cats in Quebec, Canada". Epidemiology and Infection 149. February 2021. doi:10.1017/s0950268821000364. PMID 33583452.

- ↑ "Histologic lesions in placentas of northern fur seals (callorhinus ursinus) from a population with high placental prevalence of coxiella burnetii". Journal of Wildlife Diseases 58 (2): 333–340. April 2022. doi:10.7589/jwd-d-21-00037. PMID 35245373.

- ↑ "Detection of Lyme Disease and Q Fever Agents in Wild Rodents in Central Italy". Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 15 (7): 404–411. July 2015. doi:10.1089/vbz.2015.1807. PMID 26134933.

- ↑ Arricau-Bouvery, Nathalie; Rodolakis, Annie (May 2005). "Is Q Fever an emerging or re-emerging zoonosis?". Veterinary Research 36 (3): 327–349. doi:10.1051/vetres:2005010. ISSN 0928-4249. PMID 15845229.

- ↑ "FIÈVRE Q EXPÉRIMENTALE DES BOVINS" (in fr). Annales de Recherches Vétérinaires 4 (2): 325–346. 1973. OCLC 862686843.

- ↑ "Is Q fever an emerging or re-emerging zoonosis?". Veterinary Research 36 (3): 327–349. May 2005. doi:10.1051/vetres:2005010. PMID 15845229.

- ↑ "Coxiella burnetii in Infertile Dairy Cattle With Chronic Endometritis". Veterinary Pathology 55 (4): 539–542. July 2018. doi:10.1177/0300985818760376. PMID 29566608.

- ↑ "Prevalenza di Coxiella burnetii nel latte di massa in allevamenti di bovine da latte italiani e possibile correlazione con problemi riproduttivi". https://www.vetjournal.it/images/archive/pdf_riviste/4649.pdf.

- ↑ Impact de la vaccination et de l'antibiothérapie sur l'incidence des troubles de la reproduction et sur la fertilité dans des troupeaux bovins laitiers infectés par Coxiella Burnetii. OCLC 836117348.

- ↑ "Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii infection in domestic ruminants: a critical review". Veterinary Microbiology 149 (1–2): 1–16. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.10.007. PMID 21115308.

- ↑ "Q fever and seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii in domestic ruminants". Veterinaria Italiana 54 (4): 265–279. December 2018. doi:10.12834/VetIt.1113.6046.3. PMID 30681125.

- ↑ "Q fever and prevalence of Coxiella burnetii in milk" (in en). Trends in Food Science & Technology 71: 65–72. 2018-01-01. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.004. ISSN 0924-2244.

- ↑ "Serological screening for Coxiella burnetii in the context of early pregnancy loss in dairy cows". Acta Veterinaria Hungarica 68 (3): 305–309. September 2020. doi:10.1556/004.2020.00035. PMID 33156002.

- ↑ "Prevalence of Coxiella burnetii in bovine placentas in Hungary and Slovakia: Detection of a novel sequence type - Short communication". Acta Veterinaria Hungarica 69 (4): 303–307. October 2021. doi:10.1556/004.2021.00047. PMID 34735368.

- ↑ "Prevalence and Risk Factors of Coxiella burnetii Antibodies in Bulk Milk from Cattle, Sheep, and Goats in Jordan". Journal of Food Protection 80 (4): 561–566. April 2017. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-16-377. PMID 28272921.

- ↑ "One Health Approach: An Overview of Q Fever in Livestock, Wildlife and Humans in Asturias (Northwestern Spain)". Animals 11 (5): 1395. May 2021. doi:10.3390/ani11051395. PMID 34068431.

- ↑ "Increasing prevalence of Coxiella burnetii seropositive Danish dairy cattle herds". Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 56 (1). July 2014. doi:10.1186/s13028-014-0046-2. PMID 25056416.

- ↑ "Coxiella burnetii shedding by dairy cows". Veterinary Research 38 (6): 849–860. November 2007. doi:10.1051/vetres:2007038. PMID 17903418.

- ↑ "A large outbreak of Q fever in the West Midlands: windborne spread into a metropolitan area?". Communicable Disease and Public Health 1 (3): 180–187. September 1998. PMID 9782633.

- ↑ Plummer, Paul J.; McClure, J.Trenton; Menzies, Paula; Morley, Paul S.; Van den Brom, René; Van Metre, David C. (September 2018). "Management of Coxiella burnetii infection in livestock populations and the associated zoonotic risk: A consensus statement" (in en). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 32 (5): 1481–1494. doi:10.1111/jvim.15229. PMID 30084178.

- ↑ "Coxevac | European Medicines Agency". 17 September 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/veterinary/EPAR/coxevac.

- ↑ "The Q fever epidemic in The Netherlands: history, onset, response and reflection". Epidemiology and Infection 139 (1): 1–12. January 2011. doi:10.1017/S0950268810002268. PMID 20920383.

External links

- Q fever at the CDC

- Coxiella burnetii genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

Template:Bacterial cutaneous infections

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|