Biology:Panton–Valentine leukocidin

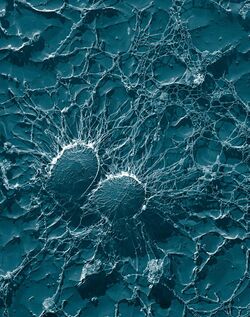

Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) is a cytotoxin—one of the β-pore-forming toxins. The presence of PVL is associated with increased virulence of certain strains (isolates) of Staphylococcus aureus. It is present in the majority[1] of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) isolates studied[2][3] and is the cause of necrotic lesions involving the skin or mucosa, including necrotic hemorrhagic pneumonia. PVL creates pores in the membranes of infected cells. PVL is produced from the genetic material of a bacteriophage that infects Staphylococcus aureus, making it more virulent.[4]

History

It was initially discovered by Van deVelde in 1894 due to its ability to lyse leukocytes. It was named after Sir Philip Noel Panton and Francis Valentine when they associated it with soft tissue infections in 1932.[5][6]

Mechanism of action

| PVL, S component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | LukS-PV | ||||||

| PDB | 1PVL (ECOD) | ||||||

| UniProt | Q783R1 | ||||||

| |||||||

| PVL, F component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | LukF-PV | ||||||

| PDB | 1T5R (ECOD) | ||||||

| UniProt | Q5FBD2 | ||||||

| |||||||

Exotoxins such as PVL constitute essential components of the virulence mechanisms of S. aureus. Nearly all strains secrete lethal factors that convert host tissues into nutrients required for bacterial growth.[7]

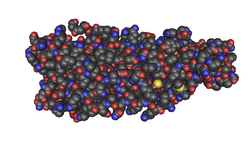

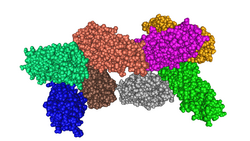

PVL is a member of the synergohymenotropic toxin family that induces pores in the membranes of cells.[8] The PVL factor is encoded in a prophage—designated as Φ-PVL—which is a virus integrated into the S. aureus bacterial chromosome.[failed verification] Its genes secrete two proteins—toxins designated LukS-PV and LukF-PV, 33 and 34 kDa[failed verification] in size. The structures of both proteins have been solved in the soluble forms, and are present in the PDB as ID codes 1t5r and 1pvl respectively.[9]

LukS-PV and LukF-PV act together as subunits, assembling in the membrane of host defense cells, in particular, white blood cells, monocytes, and macrophages.[10] The subunits fit together and form a ring with a central pore through which cell contents leak and which acts as a superantigen.[8][11] Other authors contribute the differential response of MRSA subtypes to phenol-soluble modulin (PSM) peptides and not to PVL.[12]

Clinical effects

PVL causes leukocyte destruction and necrotizing pneumonia, an aggressive condition that can kill up to 75% of patients.[13] Comparing cases of staphylococcal necrotizing pneumonia, 85% of community-acquired (CAP) cases were PVL-positive, while none of the hospital-acquired cases were. CAP afflicted younger and healthier patients and yet had a worse outcome (>40% mortality.)[8] It has played a role in a number of outbreaks of fatal bacterial infections.[14] PVL may increase the expression of staphylococcal protein A, a key pro-inflammatory factor for pneumonia.[15]

Epidemiology

Panton–Valentine leukocidin (PVL) is one of many toxins associated with S. aureus infection. Because it can be found in virtually all CA-MRSA strains that cause soft-tissue infections, it was long described as a key virulence factor, allowing the bacteria to target and kill specific white blood cells known as neutrophils. This view was challenged, however, when it was shown that removal of PVL from the two major epidemic CA-MRSA strains resulted in no loss of infectivity or destruction of neutrophils in a mouse model.[16][17]

Genetic analysis shows that PVL CA-MRSA has emerged several times, on different continents, rather than being the worldwide spread of a single clone.[18]

References

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2007-02-24). "Community-Associated Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA)". https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/ar_mrsa_ca.html.

- ↑ Szmiegielski S; Prevost G; Monteil H et al. (1999). "Leukocidal toxins of staphylococci". Zentralbl Bakteriol 289 (2): 185–201. doi:10.1016/S0934-8840(99)80105-4. PMID 10360319. http://md1.csa.com/partners/viewrecord.php?requester=gs&collection=ENV&recid=4585549&q=&uid=791585049&setcookie=yes. Retrieved 2007-11-01.

- ↑ "Bacterial two-component and hetero-heptameric pore-forming cytolytic toxins: structures, pore-forming mechanism, and organization of the genes". Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68 (5): 981–1003. 2004. doi:10.1271/bbb.68.981. PMID 15170101.

- ↑ "Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia". Clin Infect Dis 29 (5): 1128–1132. 1999. doi:10.1086/313461. PMID 10524952.

- ↑ Panton, P.N.; Came, M.B.; Valentine, F.C.O.; Lond, M.R.C.P. (March 1932). "Staphylococcal Toxin". The Lancet 1 (5662): 506–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)24468-7. https://dspace.ubib.eur.nl/bitstream/1765/7927/1/PVL.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-06.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the role of Panton–Valentine leukocidin". Lab Invest 87 (1): 3–9. 2007. doi:10.1038/labinvest.3700501. PMID 17146447.

- ↑ Boubaker K; Diebold P; Blanc DS et al. (January 2004). "Panton-valentine leukocidin and staphyloccoccal skin infections in schoolchildren". Emerging Infect. Dis. 10 (1): 121–4. doi:10.3201/eid1001.030144. PMID 15078606. PMC 3322757. https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol10no1/03-0144.htm.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Suzanne F. Bradley (2006-02-22). "The Role of Toxins in the Changing Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation of Staphylococcal Pneumonia". p. 6. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/521338_6.

- ↑ "PDBe Protein Data Bank in Europe". http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe-apps/quips?story=PantonValentine.

- ↑ "Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes in Staphylococcus aureus". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (7): 1174–5. July 2006. doi:10.3201/eid1207.050865. PMID 16848048. PMC 3375734. https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol12no07/05-0865.htm.

- ↑ Deresinski S (February 2005). "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an evolutionary, epidemiologic, and therapeutic odyssey". Clin. Infect. Dis. 40 (4): 562–573. doi:10.1086/427701. PMID 15712079.

- ↑ Spentzas, Thomas; Kudumula, Ravi; Acuna, Carlos; Talati, Ajay J.; Ingram, Kimberly C.; Savorgnan, Fabio; Meals, Elizabeth A.; English, B. Keith (2011-01-01). "Role of bacterial components in macrophage activation by the LAC and MW2 strains of community-associated, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus". Cellular Immunology 269 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.03.009. ISSN 1090-2163. PMID 21458780.

- ↑ "Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients". Lancet 359 (9308): 753–9. 2002. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07877-7. PMID 11888586.

- ↑ The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2-2516306,00.html.

- ↑ "Staphylococcus aureus Toxin Can Cause Necrotizing Pneumonia". Medscape. 2007-01-18. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/550968.

- ↑ MRSA Toxin Acquitted: Study Clears Suspected Key to Severe Bacterial Illness , NIH news release, Nov. 6, 2006

- ↑ Voyich JM; Otto M; Mathema B et al. (2006). "Is Panton-Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease?". J. Infect. Dis. 194 (12): 1761–1770. doi:10.1086/509506. PMID 17109350.

- ↑ "Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence". Emerg Infect Dis 9 (8): 978–84. August 2003. doi:10.3201/eid0908.030089. PMID 12967497. PMC 3020611. https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/Eid/vol9no8/pdfs/03-0089.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

External links

- Panton-Valentine+leukocidin at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

|