Biology:Clostridium botulinum

| Clostridium botulinum | |

|---|---|

| |

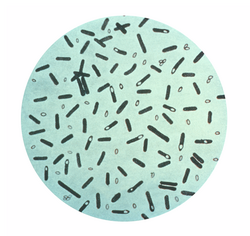

| Clostridium botulinum stained with gentian violet. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Bacillota |

| Class: | Clostridia |

| Order: | Eubacteriales |

| Family: | Lachnospiraceae |

| Genus: | Clostridium |

| Species: | C. botulinum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Clostridium botulinum van Ermengem, 1896

| |

Clostridium botulinum is a gram-positive,[1] rod-shaped, anaerobic, spore-forming, motile bacterium with the ability to produce the neurotoxin botulinum.[2][3]

The botulinum toxin can cause botulism, a severe flaccid paralytic disease in humans and other animals,[3] and is the most potent toxin known to science, natural or synthetic, with a lethal dose of 1.3–2.1 ng/kg in humans.[4][5]

C. botulinum is a diverse group of pathogenic bacteria initially grouped together by their ability to produce botulinum toxin and now known as four distinct groups, C. botulinum groups I–IV, as well as some strains of Clostridium butyricum and Clostridium baratii, are the bacteria responsible for producing botulinum toxin.[2]

C. botulinum is responsible for foodborne botulism (ingestion of preformed toxin), infant botulism (intestinal infection with toxin-forming C. botulinum), and wound botulism (infection of a wound with C. botulinum). C. botulinum produces heat-resistant endospores that are commonly found in soil and are able to survive under adverse conditions.[2]

C. botulinum is commonly associated with bulging canned food; bulging, misshapen cans can be due to an internal increase in pressure caused by gas produced by bacteria.[6]

Microbiology

C. botulinum is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacterium.[7] It is an obligate anaerobe, meaning that oxygen is poisonous to the cells. However, C. botulinum tolerates traces of oxygen due to the enzyme superoxide dismutase, which is an important antioxidant defense in nearly all cells exposed to oxygen.[8] C. botulinum is able to produce the neurotoxin only during sporulation, which can happen only in an anaerobic environment.

C. botulinum is divided into four distinct phenotypic groups (I-IV) and is also classified into seven serotypes (A–G) based on the antigenicity of the botulinum toxin produced.[9][10] On the level visible to DNA sequences, the phenotypic grouping matches the results of whole-genome and rRNA analyses,[11][12] and setotype grouping approximates the result of analyses focused specifically on the toxin sequence. The two phylogenetic trees do not match because of the ability of the toxin gene cluster to be horizontally transferred.[13]

Serotypes

Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) production is the unifying feature of the species. Seven serotypes of toxins have been identified that are allocated a letter (A–G), several of which can cause disease in humans. They are resistant to degradation by enzymes found in the gastrointestinal tract. This allows for ingested toxins to be absorbed from the intestines into the bloodstream.[5] Toxins can be further differentiated into subtypes on the bases of smaller variations.[14] However, all types of botulinum toxin are rapidly destroyed by heating to 100 °C for 15 minutes (900 seconds). 80 °C for 30 minutes also destroys BoNT.[15][16]

Most strains produce one type of BoNT, but strains producing multiple toxins have been described. C. botulinum producing B and F toxin types have been isolated from human botulism cases in New Mexico and California .[17] The toxin type has been designated Bf as the type B toxin was found in excess to the type F. Similarly, strains producing Ab and Af toxins have been reported.[citation needed]

Evidence indicates the neurotoxin genes have been the subject of horizontal gene transfer, possibly from a viral (bacteriophage) source. This theory is supported by the presence of integration sites flanking the toxin in some strains of C. botulinum. However, these integrations sites are degraded (except for the C and D types), indicating that the C. botulinum acquired the toxin genes quite far in the evolutionary past. Nevertheless, further transfers still happen via the plasmids and other mobile elements the genes are located on.[18]

Toxin types in disease

Only botulinum toxin types A, B, E, F and H (FA) cause disease in humans. Types A, B, and E are associated with food-borne illness, while type E is specifically associated with fish products. Type C produces limber-neck in birds and type D causes botulism in other mammals. No disease is associated with type G.[19] The "gold standard" for determining toxin type is a mouse bioassay, but the genes for types A, B, E, and F can now be readily differentiated using quantitative PCR.[20] Type "H" is in fact a recombinant toxin from types A and F. It can be neutralized by type A antitoxin and no longer is considered a distinct type.[21]

A few strains from organisms genetically identified as other Clostridium species have caused human botulism: C. butyricum has produced type E toxin[22] and C. baratii had produced type F toxin.[23] The ability of C. botulinum to naturally transfer neurotoxin genes to other clostridia is concerning, especially in the food industry, where preservation systems are designed to destroy or inhibit only C. botulinum but not other Clostridium species.[citation needed]

Groups

Physiological differences and genome sequencing at 16S rRNA level support the subdivision of the C. botulinum species into groups I-IV.[11] Some authors have briefly used groups V and VI, corresponding to toxin-producing C. baratii and C. butyricum. What used to be group IV is now C. argentinense.[24]

| Property | Group I | Group II | Group III | C. argentinense | C. baratii | C. butyricum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteolysis (casein) | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| Saccharolysis | - | + | - | - | ||

| Lipase | + | + | + | - | - | - |

| Toxin Types | A, B, F | B, E, F | C, D | G | F | E |

| Toxin gene | chromosome/plasmid | chromosome/plasmid | bacteriophage | plasmid | chromosome[25] | chromosome[26] |

| Close relatives |

|

|

|

N/A (already a species) | ||

Although group II cannot degrade native protein such as casein, coagulated egg white, and cooked meat particles, it is able to degrade gelatin.[27]

Human botulism is predominantly caused by group I or II C. botulinum.[27] Group III organisms mainly cause diseases in non-human animals.[27]

Laboratory isolation

In the laboratory, C. botulinum is usually isolated in tryptose sulfite cycloserine (TSC) growth medium in an anaerobic environment with less than 2% oxygen. This can be achieved by several commercial kits that use a chemical reaction to replace O2 with CO2. C. botulinum (groups I through III) is a lipase-positive microorganism that grows between pH of 4.8 and 7.0 and cannot use lactose as a primary carbon source, characteristics important for biochemical identification.[28]

Taxonomic history

| NCBI genome ID | 726 |

|---|---|

| Ploidy | haploid |

| Genome size | 3.91 Mb |

| Number of chromosomes | 2 (1 plasmid) |

| Year of completion | 2007 |

C. botulinum was first recognized and isolated in 1895 by Emile van Ermengem from home-cured ham implicated in a botulism outbreak.[29] The isolate was originally named Bacillus botulinus, after the Latin word for sausage, botulus. ("Sausage poisoning" was a common problem in 18th- and 19th-century Germany, and was most likely caused by botulism.)[30] However, isolates from subsequent outbreaks were always found to be anaerobic spore formers, so Ida A. Bengtson proposed that both be placed into the genus Clostridium, as the genus Bacillus was restricted to aerobic spore-forming rods.[31]

Since 1959, all species producing the botulinum neurotoxins (types A–G) have been designated C. botulinum. Substantial phenotypic and genotypic evidence exists to demonstrate heterogeneity within the species, with at least four clearly-defined "groups" (see § Groups) straddling other species, implying that they each deserve to be a genospecies.[32][24]

The situation as of 2018 is as follows:[24]

- C. botulinum type G (= group IV) strains are since 1988 their own species, C. argentinense.[33]

- Group I C. botulinum strains that do not produce a botulin toxin are referred to as C. sporogenes. Both names are conserved names since 1999.[34] Group I also contains C. combesii.[35]

- All other botulinum toxin-producing bacteria, not otherwise classified as C. baratii or C. butyricum,[36] is called C. botulinum. This group still contains three genogroups.[24]

Smith et al. (2018) argues that group I should be called C. parabotulinum and group III be called C. novyi sensu lato, leaving only group II in C. botulinum. This argument is not accepted by the LPSN and would cause an unjustified change of the type strain under the Prokaryotic Code.[24] Dobritsa et al. (2018) argues, without formal descriptions, that group II can potentially be made into two new species.[12]

The complete genome of C. botulinum ATCC 3502 has been sequenced at Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in 2007. This strain encodes a type "A" toxin.[37]

Pathology

Foodborne botulism

"Signs and symptoms of foodborne botulism typically begin between 18 and 36 hours after the toxin gets into your body, but can range from a few hours to several days, depending on the amount of toxin ingested."[38]

- Double vision

- Blurred vision

- Drooping eyelids (ptosis)

- Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps

- Slurred speech

- Trouble breathing

- Difficulty in swallowing

- Dry mouth

- Muscle weakness

- Constipation

- Reduced or absent deep tendon reactions, such as in the knee

Wound botulism

Most people who develop wound botulism inject drugs several times a day, so it is difficult to determine how long it takes for signs and symptoms to develop after the toxin enters the body. Most common in people who inject black tar heroin, wound botulism signs and symptoms include:[38]

- Difficulty swallowing or speaking

- Facial weakness on both sides of the face

- Blurred or double vision

- Drooping eyelids (ptosis)

- Trouble breathing

- Paralysis

Infant botulism

If infant botulism is related to food, such as honey, problems generally begin within 18 to 36 hours after the toxin enters the baby's body. Signs and symptoms include:[38]

- Constipation (often the first sign)

- Floppy movements due to muscle weakness and trouble controlling the head

- Weak cry

- Irritability

- Drooling

- Drooping eyelids (ptosis)

- Tiredness

- Difficulty sucking or feeding

- Paralysis[38]

Beneficial effects of botulinum toxin

Purified botulinum toxin is diluted by a physician for treatment of:

- Congenital pelvic tilt

- Spasmodic dysphasia (the inability of the muscles of the larynx)

- Achalasia (esophageal stricture)

- Strabismus (crossed eyes)

- Paralysis of the facial muscles

- Failure of the cervix

- Blinking frequently

- Anti-cancer drug delivery[39]

Adult intestinal toxemia

A very rare form of botulism that occurs by the same route as infant botulism but is among adults. Occurs rarely and sporadically. Signs and symptoms include:

- Abdominal pain

- Blurred vision

- Diarrhea

- Dysarthria

- Imbalance

- Weakness in arms and hand area[40]

C. botulinum in different geographical locations

A number of quantitative surveys for C. botulinum spores in the environment have suggested a prevalence of specific toxin types in given geographic areas, which remain unexplained.[citation needed]

North America

Type A C. botulinum predominates the soil samples from the western regions, while type B is the major type found in eastern areas.[41] The type-B organisms were of the proteolytic type I. Sediments from the Great Lakes region were surveyed after outbreaks of botulism among commercially reared fish, and only type E spores were detected.[42][43][44] In a survey, type-A strains were isolated from soils that were neutral to alkaline (average pH 7.5), while type-B strains were isolated from slightly acidic soils (average pH 6.23).[citation needed]

Europe

C. botulinum type E is prevalent in aquatic sediments in Norway and Sweden,[45] Denmark,[46] the Netherlands, the Baltic coast of Poland, and Russia.[41] The type-E C. botulinum was suggested to be a true aquatic organism, which was indicated by the correlation between the level of type-E contamination and flooding of the land with seawater. As the land dried, the level of type E decreased and type B became dominant.[citation needed]

In soil and sediment from the United Kingdom, C. botulinum type B predominates. In general, the incidence is usually lower in soil than in sediment. In Italy, a survey conducted in the vicinity of Rome found a low level of contamination; all strains were proteolytic C. botulinum types A or B.[47]

Australia

C. botulinum type A was found to be present in soil samples from mountain areas of Victoria.[48] Type-B organisms were detected in marine mud from Tasmania.[49][verification needed] Type-A C. botulinum has been found in Sydney suburbs and types A and B were isolated from urban areas. In a well-defined area of the Darling-Downs region of Queensland, a study showed the prevalence and persistence of C. botulinum type B after many cases of botulism in horses.[50]

Use and detection

C. botulinum is used to prepare the medicaments Botox, Dysport, Xeomin, and Neurobloc used to selectively paralyze muscles to temporarily relieve muscle function. It has other "off-label" medical purposes, such as treating severe facial pain, such as that caused by trigeminal neuralgia.[citation needed]

Botulinum toxin produced by C. botulinum is often believed to be a potential bioweapon as it is so potent that it takes about 75 nanograms to kill a person (-1">50 of 1 ng/kg,[51] assuming an average person weighs ~75 kg); 1 kilogram of it would be enough to kill the entire human population.

A "mouse protection" or "mouse bioassay" test determines the type of C. botulinum toxin present using monoclonal antibodies. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with digoxigenin-labeled antibodies can also be used to detect the toxin,[52] and quantitative PCR can detect the toxin genes in the organism.[20]

Growth conditions and prevention

C. botulinum is a soil bacterium. The spores can survive in most environments and are very hard to kill. They can survive the temperature of boiling water at sea level, thus many foods are canned with a pressurized boil that achieves even higher temperatures, sufficient to kill the spores.[53][54] This bacteria is widely distributed in nature and can be assumed to be present on all food surfaces. Its optimum growth temperature is within the mesophilic range. In spore form, it is a heat resistant pathogen that can survive in low acid foods and grow to produce toxins. The toxin attacks the nervous system and will kill an adult at a dose of around 75 ng.[51] This toxin is detoxified by holding food at 100 °C for 10 minutes.[55]

Botulism poisoning can occur due to preserved or home-canned, low-acid food that was not processed using correct preservation times and/or pressure.[56] Growth of the bacterium can be prevented by high acidity, high ratio of dissolved sugar, high levels of oxygen, very low levels of moisture, or storage at temperatures below 3 °C (38 °F) for type A. For example, in a low-acid, canned vegetable such as green beans that are not heated enough to kill the spores (i.e., a pressurized environment) may provide an oxygen-free medium for the spores to grow and produce the toxin. However, pickles are sufficiently acidic to prevent growth;[non-primary source needed] even if the spores are present, they pose no danger to the consumer.

Honey, corn syrup, and other sweeteners may contain spores, but the spores cannot grow in a highly concentrated sugar solution; however, when a sweetener is diluted in the low-oxygen, low-acid digestive system of an infant, the spores can grow and produce toxin. As soon as infants begin eating solid food, the digestive juices become too acidic for the bacterium to grow.[57]

The control of food-borne botulism caused by C. botulinum is based almost entirely on thermal destruction (heating) of the spores or inhibiting spore germination into bacteria and allowing cells to grow and produce toxins in foods. Conditions conducive of growth are dependent on various environmental factors. Growth of C. botulinum is a risk in low acid foods as defined by having a pH above 4.6[58] although growth is significantly retarded for pH below 4.9.[citation needed]

In the beginning of 21st century there have been some cases and specific conditions reported to sustain growth with pH below 4.6. but at higher temperature.[59][60]

Diagnosis

Physicians may consider the diagnosis of botulism based on a patient's clinical presentation, which classically includes an acute onset of bilateral cranial neuropathies and symmetric descending weakness.[61][62] Other key features of botulism include an absence of fever, symmetric neurologic deficits, normal or slow heart rate and normal blood pressure, and no sensory deficits except for blurred vision.[63][64] A careful history and physical examination is paramount in order to diagnose the type of botulism, as well as to rule out other conditions with similar findings, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, stroke, and myasthenia gravis.[citation needed] Depending on the type of botulism considered, different tests for diagnosis may be indicated.

- Foodborne botulism: serum analysis for toxins by bioassay in mice should be done, as the demonstration of the toxins is diagnostic.[65]

- Wound botulism: isolation of C. botulinum from the wound site should be attempted, as growth of the bacteria is diagnostic.[66]

- Adult enteric and infant botulism: isolation and growth of C. botulinum from stool samples is diagnostic.[67] Infant botulism is a diagnosis which is often missed in the emergency room.[citation needed]

Other tests that may be helpful in ruling out other conditions are:

- Electromyography (EMG) or antibody studies may help with the exclusion of myasthenia gravis and Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS).[68]

- Collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein and blood assist with the exclusion of Guillan-Barre syndrome and stroke.[69]

- Detailed physical examination of the patient for any rash or tick presence helps with the exclusion of any tick transmitted tick paralysis.[70]

Treatment

In the case of a diagnosis or suspicion of botulism, patients should be hospitalized immediately, even if the diagnosis and/or tests are pending. If botulism is suspected, patients should be treated immediately with antitoxin therapy in order to reduce mortality. Immediate intubation is also highly recommended, as respiratory failure is the primary cause of death from botulism.[71][72][73]

In North America, an equine-derived heptavalent botulinum antitoxin is used to treat all serotypes of non-infant naturally occurring botulism. For infants less than one year of age, botulism immune globulin is used to treat type A or type B.[74][75]

Outcomes vary between one and three months, but with prompt interventions, mortality from botulism ranges from less than 5 percent to 8 percent.[76]

Vaccination

There used to be a formalin-treated toxoid vaccine against botulism (serotypes A-E), but it was discontinued in 2011 due to declining potency in the toxoid stock. It was originally intended for people at risk of exposure. A few new vaccines are under development.[77]

References

- ↑ Tiwari, Aman; Nagalli, Shivaraj (2021), "Clostridium Botulinum", StatPearls (Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing), PMID 31971722, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553081/, retrieved 2021-09-23

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Biology and Genomic Analysis of Clostridium botulinum. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 55. 2009. 183–265, 320. doi:10.1016/s0065-2911(09)05503-9. ISBN 9780123747907.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Laboratory diagnostics of botulism". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19 (2): 298–314. April 2006. doi:10.1128/cmr.19.2.298-314.2006. PMID 16614251.

- ↑ Košenina, Sara; Masuyer, Geoffrey; Zhang, Sicai; Dong, Min; Stenmark, Pål (June 2019). "Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of the Weissella oryzae botulinum-like toxin" (in en). FEBS Letters 593 (12): 1403–1410. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.13446. ISSN 0014-5793. PMID 31111466.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 (2010). Chapter 19. Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides, and Other Anaerobes. In Ryan K.J., Ray C (Eds), Sherris Medical Microbiology, 5th ed. ISBN:978-0-07-160402-4

- ↑ "Preventing Foodborne Illness: Clostridium botulinum" (in en). University of Florida IFAS Extension. 9 January 2015. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/fs104.

- ↑ Tiwari, Aman; Nagalli, Shivaraj (2023) (in English). Clostridium botulinum. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers. ASM Press. 2007. ISBN 978-1-55581-208-9.

- ↑ "Clostridium botulinum in the post-genomic era". Food Microbiology 28 (2): 183–91. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2010.03.005. PMID 21315972.

- ↑ "Clostridium botulinum: a bug with beauty and weapon". Critical Reviews in Microbiology 31 (1): 11–8. 2005. doi:10.1080/10408410590912952. PMID 15839401.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Austin, J.W. (January 1, 2003). "CLOSTRIDIUM | Occurrence of Clostridium botulinum". CLOSTRIDIUM. Academic Press. pp. 1407–1413. doi:10.1016/B0-12-227055-X/00255-8. ISBN 9780122270550. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B012227055X002558. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Dobritsa, Anatoly P.; Kutumbaka, Kirthi K.; Samadpour, Mansour (1 September 2018). "Reclassification of Eubacterium combesii and discrepancies in the nomenclature of botulinum neurotoxin-producing clostridia: Challenging Opinion 69. Request for an Opinion". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 68 (9): 3068–3075. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.002942. PMID 30058996.

- ↑ Hill, Karen K.; Smith, Theresa J. (2012). "Genetic Diversity Within Clostridium botulinum Serotypes, Botulinum Neurotoxin Gene Clusters and Toxin Subtypes". Botulinum Neurotoxins. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 364. pp. 1–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-33570-9_1. ISBN 978-3-642-33569-3. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233914979.

- ↑ Peck, MW; Smith, TJ; Anniballi, F; Austin, JW; Bano, L; Bradshaw, M; Cuervo, P; Cheng, LW et al. (18 January 2017). "Historical Perspectives and Guidelines for Botulinum Neurotoxin Subtype Nomenclature.". Toxins 9 (1): 38. doi:10.3390/toxins9010038. PMID 28106761.

- ↑ "Removal and inactivation of botulinum toxin during production of drinking water from surface water". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 46 (5): 511–514. 1980. doi:10.1007/BF00395840.

- ↑ "Botulinal neurotoxins: revival of an old killer". Current Opinion in Pharmacology 5 (3): 274–9. June 2005. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.006. PMID 15907915.

- ↑ "Examination of feces and serum for diagnosis of infant botulism in 336 patients". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 25 (12): 2334–8. December 1987. doi:10.1128/JCM.25.12.2334-2338.1987. PMID 3323228.

- ↑ "Why Are Botulinum Neurotoxin-Producing Bacteria So Diverse and Botulinum Neurotoxins So Toxic?". Toxins 11 (1): 34. January 2019. doi:10.3390/toxins11010034. PMID 30641949.

- ↑ (2013). Chapter 11. Spore-Forming Gram-Positive Bacilli: Bacillus and Clostridium Species. In Brooks G.F., Carroll K.C., Butel J.S., Morse S.A., Mietzner T.A. (Eds), Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg's Medical Microbiology, 26th ed. ISBN:978-0-07-179031-4

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "A quadruplex real-time PCR assay for rapid detection and differentiation of the Clostridium botulinum toxin genes A, B, E and F". Journal of Medical Microbiology 59 (Pt 1): 55–64. January 2010. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.012567-0. PMID 19779029.

- ↑ Maslanka, SE; Lúquez, C; Dykes, JK; Tepp, WH; Pier, CL; Pellett, S; Raphael, BH; Kalb, SR et al. (1 February 2016). "A Novel Botulinum Neurotoxin, Previously Reported as Serotype H, Has a Hybrid-Like Structure With Regions of Similarity to the Structures of Serotypes A and F and Is Neutralized With Serotype A Antitoxin.". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 213 (3): 379–85. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv327. PMID 26068781.

- ↑ "Two cases of type E infant botulism caused by neurotoxigenic Clostridium butyricum in Italy". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 154 (2): 207–11. August 1986. doi:10.1093/infdis/154.2.207. PMID 3722863.

- ↑ "Isolation of an organism resembling Clostridium barati which produces type F botulinal toxin from an infant with botulism". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 21 (4): 654–5. April 1985. doi:10.1128/JCM.21.4.654-655.1985. PMID 3988908.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Smith, Theresa; Williamson, Charles H. D.; Hill, Karen; Sahl, Jason; Keim, Paul (7 November 2018). "Botulinum Neurotoxin-Producing Bacteria. Isn't It Time that We Called a Species a Species?". mBio 9 (5). doi:10.1128/mbio.01469-18. PMID 30254123.

- ↑ Mazuet, C; Legeay, C; Sautereau, J; Bouchier, C; Criscuolo, A; Bouvet, P; Trehard, H; Jourdan Da Silva, N et al. (1 February 2017). "Characterization of Clostridium Baratii Type F Strains Responsible for an Outbreak of Botulism Linked to Beef Meat Consumption in France.". PLOS Currents 9. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.6ed2fe754b58a5c42d0c33d586ffc606. PMID 29862134.

- ↑ Hill, Karen K; Xie, Gary; Foley, Brian T; Smith, Theresa J; Munk, Amy C; Bruce, David; Smith, Leonard A; Brettin, Thomas S et al. (December 2009). "Recombination and insertion events involving the botulinum neurotoxin complex genes in Clostridium botulinum types A, B, E and F and Clostridium butyricum type E strains". BMC Biology 7 (1): 66. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-66. PMID 19804621.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Carter, Andrew T.; Peck, Michael W. (October 18, 1957). "Genomes, neurotoxins and biology of Clostridium botulinum Group I and Group II". Research in Microbiology 166 (4): 303–317. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2014.10.010. PMID 25445012.

- ↑ Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. 2005. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.

- ↑ "Über einen neuen anaeroben Bacillus und seine Beziehungen Zum Botulismus". Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten 26: 1–8. 1897.

- ↑ "Historical notes on botulism, Clostridium botulinum, botulinum toxin, and the idea of the therapeutic use of the toxin". Movement Disorders 19 (Suppl 8): S2-6. March 2004. doi:10.1002/mds.20003. PMID 15027048.

- ↑ "Studies on organisms concerned as causative factors in botulism". Bulletin (Hygienic Laboratory (U.S.)) 136: 101 fv. 1924. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015007772703.

- ↑ Uzal, Francisco A.; Songer, J. Glenn; Prescott, John F.; Popoff, Michel R. (21 June 2016). "Taxonomic Relationships among the Clostridia". Clostridial Diseases of Animals. doi:10.1002/9781118728291.ch1. ISBN 9781118728291.

- ↑ "Clostridium argentinense sp.nov.: a genetically homogeneous group composed of all strains of Clostridium botulinum type G and some nonttoxigenic strains previously identified as Clostridium subterminale or Clostridium hastiforme". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 38: 375–381. 1988. doi:10.1099/00207713-38-4-375.

- ↑ "Rejection of Clostridium putrificum and conservation of Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium sporogenes-Opinion 69. Judicial Commission of the International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 49 (1): 339. January 1999. doi:10.1099/00207713-49-1-339. PMID 10028279.

- ↑ "Species: Clostridium combesii" (in en). https://lpsn.dsmz.de/species/clostridium-combesii.

- ↑ Arahal, David R.; Busse, Hans-Jürgen; Bull, Carolee T.; Christensen, Henrik; Chuvochina, Maria; Dedysh, Svetlana N.; Fournier, Pierre-Edouard; Konstantinidis, Konstantinos T. et al. (10 August 2022). "Judicial Opinions 112–122". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 72 (8). doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.005481. PMID 35947640. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362626093. "This means that if a strain is supposed to belong to either Clostridium botulinum or Clostridium sporogenes or both, the correct species name of the strain is Clostridium botulinum if the strain is toxigenic but is Clostridium sporogenes if the strain is nontoxigenic. The two species names are only conserved against each other. Opinion 69 does not apply to strains that are not supposed to belong to Clostridium botulinum and are not supposed to belong to Clostridium sporogenes.".

- ↑ "Clostridium botulinum A str. ATCC 3502 genome assembly ASM6358v1" (in en). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_000063585.1/.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 "Botulism Symptoms". Mayo Clinic. June 13, 2015. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/botulism/basics/symptoms/con-20025875.

- ↑ "Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management". JAMA 285 (8): 1059–70. February 2001. doi:10.1001/jama.285.8.1059. PMID 11209178.

- ↑ "Botulism". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. 23 October 2016.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Hauschild, A. H. W. (1989). "Clostridium botulinum". in Doyle, M. P.. Food-borne Bacterial Pathogens. New York: Marcel Dekker. pp. 111–189. ISBN 0-8247-7866-9.

- ↑ "Possible origin of the high incidence of Clostridium botulinum type E in an inland bay (Green Bay of Lake Michigan)". Journal of Bacteriology 95 (5): 1542–7. May 1968. doi:10.1128/JB.95.5.1542-1547.1968. PMID 4870273.

- ↑ "Botulism in juvenile Coho salmon (Onocorhynchus kisutch) in the United States". Aquaculture 27 (1): 1–11. 1982. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(82)90104-1. Bibcode: 1982Aquac..27....1E.

- ↑ "Type E botulism in salmonids and conditions contributing to outbreaks". Aquaculture 41 (4): 293–309. 1984. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(84)90198-4. Bibcode: 1984Aquac..41..293E.

- ↑ Johannsen, A. (1963). "Clostridium botulinum in Sweden and the adjacent waters". Journal of Applied Microbiology 26 (1): 43–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1963.tb01153.x.

- ↑ "Distribution of Clostridium botulinum". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 39 (4): 764–9. April 1980. doi:10.1128/AEM.39.4.764-769.1980. PMID 6990867. Bibcode: 1980ApEnM..39..764H.

- ↑ "Occurrence of Clostridium botulinum in the soil of the vicinity of Rome". Current Microbiology 20 (5): 317. 1990. doi:10.1007/bf02091912.

- ↑ "The isolation of Clostridium botulinum type A from Victorian soils". The Australian Journal of Science 10 (1): 20. August 1947. PMID 20267540.

- ↑ "Studies in the physiology of Clostridium botulinum type E.". Australian Journal of Biological Sciences 10: 85–94. 1957. doi:10.1071/BI9570085.

- ↑ Thomas, R. J.; Rosenthal, D. V.; Rogers, R. J. (March 1988). "A Clostridium botulinum type B vaccine for prevention of shaker foal syndrome". Australian Veterinary Journal 65 (3): 78–80. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1988.tb07364.x. ISSN 0005-0423. PMID 3041951. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3041951.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Biological Safety: principles and practices. 2000. ASM Press. p. 267.

- ↑ "Detection of type A, B, E, and F Clostridium botulinum neurotoxins in foods by using an amplified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with digoxigenin-labeled antibodies". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 72 (2): 1231–8. February 2006. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.2.1231-1238.2006. PMID 16461671. Bibcode: 2006ApEnM..72.1231S.

- ↑ CDC (2019-06-06). "Prevent Botulism" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/consumer.html.

- ↑ "Botulism: take care when canning low-acid foods" (in en). https://extension.umn.edu/sanitation-and-illness/botulism.

- ↑ "CHAPTER 13: Clostridium botulinum Toxin Formation". https://www.fda.gov/files/food/published/Fish-and-Fishery-Products-Hazards-and-Controls-Guidance-Chapter-13-Download.pdf.

- ↑ "Home Canning and Botulism". https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/communication/home-canning-and-botulism.html#:~:text=Pressure%20canning%20is%20the%20only,meats%2C%20fish%2C%20and%20seafood.

- ↑ "Botulism". https://www.lecturio.com/concepts/botulism/.

- ↑ "Guidance for Commercial Processors of Acidified & Low-Acid Canned Foods". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/AcidifiedLACF/default.htm.

- ↑ "The effect of acid pH on the probability of growth of proteolytic strains of Clostridium botulinum". International Journal of Food Microbiology 4 (3): 215–226. June 1987. doi:10.1016/0168-1605(87)90039-0.

- ↑ "Clostridium botulinum can grow and form toxin at pH values lower than 4.6". Nature 281 (5730): 398–9. October 1979. doi:10.1038/281398a0. PMID 39257. Bibcode: 1979Natur.281..398R.

- ↑ "Clinical spectrum of botulism". Muscle & Nerve 21 (6): 701–10. June 1998. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199806)21:6<701::aid-mus1>3.0.co;2-b. PMID 9585323.

- ↑ "Botulism diagnostics: from clinical symptoms to in vitro assays". Critical Reviews in Microbiology 33 (2): 109–25. April 2007. doi:10.1080/10408410701364562. PMID 17558660.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and Treatment | Botulism" (in en-us). CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/botulism/testing-treatment.html.

- ↑ "Botulism: Rare but serious food poisoning" (in en). Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/botulism/basics/symptoms/con-20025875.

- ↑ "Laboratory diagnostics of botulism". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 19 (2): 298–314. April 2006. doi:10.1128/CMR.19.2.298-314.2006. PMID 16614251.

- ↑ "Improvement in laboratory diagnosis of wound botulism and tetanus among injecting illicit-drug users by use of real-time PCR assays for neurotoxin gene fragments". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 43 (9): 4342–8. September 2005. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.9.4342-4348.2005. PMID 16145075.

- ↑ "Selective medium for isolation of Clostridium botulinum from human feces". Journal of Clinical Microbiology 13 (3): 526–31. March 1981. doi:10.1128/JCM.13.3.526-531.1981. PMID 7016901.

- ↑ "Autonomic dysfunction in the Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: serologic and clinical correlates". Neurology 50 (1): 88–93. January 1998. doi:10.1212/wnl.50.1.88. PMID 9443463. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9443463/.

- ↑ "Wound botulism". Veterinary and Human Toxicology 36 (3): 233–7. June 1994. PMID 8066973. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8066973/.

- ↑ "Neurotoxin-induced paralysis: a case of tick paralysis in a 2-year-old child". Pediatric Neurology 50 (6): 605–7. June 2014. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.041. PMID 24679414.

- ↑ "Survival analysis for respiratory failure in patients with food-borne botulism". Clinical Toxicology 48 (3): 177–83. March 2010. doi:10.3109/15563651003596113. PMID 20184431.

- ↑ "Clinical predictors of respiratory failure and long-term outcome in black tar heroin-associated wound botulism". Chest 120 (2): 562–6. August 2001. doi:10.1378/chest.120.2.562. PMID 11502659.

- ↑ "Signs and symptoms predictive of respiratory failure in patients with foodborne botulism in Thailand". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 77 (2): 386–9. August 2007. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.386. PMID 17690419.

- ↑ Canada, Health (2012-07-18). "Botulism - Guide for Healthcare Professionals". https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/food-nutrition/legislation-guidelines/guidance-documents/botulism-guide-healthcare-professionals-2012.html.

- ↑ "Investigational Heptavalent Botulinum Antitoxin (HBAT) to Replace Licensed Botulinum Antitoxin AB and Investigational Botulinum Antitoxin E". https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5910a4.htm.

- ↑ "Signs and symptoms predictive of death in patients with foodborne botulism--Republic of Georgia, 1980-2002". Clinical Infectious Diseases 39 (3): 357–62. August 2004. doi:10.1086/422318. PMID 15307002.

- ↑ "Vaccines against Botulism". Toxins 9 (9): 268. September 2017. doi:10.3390/toxins9090268. PMID 28869493.

External links

- "Botulism". Clinical Infectious Diseases 41 (8): 1167–73. October 2005. doi:10.1086/444507. PMID 16163636.

Wikidata ☰ Q131268 entry

|