Exponential function: Difference between revisions

imported>Ohm simplify |

over-write |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Mathematical function, denoted exp(x) or e^x}} | {{Short description|Mathematical function, denoted exp(x) or e^x}} | ||

{{About|the function {{math|{{var|f}}({{var|x}}) {{=}} {{var|e}}{{sup|{{var|x}}}}}} and its generalizations|functions of the form {{math|{{var|f}}({{var|x}}) {{=}} {{var|x}}{{sup|{{var|r}}}}}}|Power function|the bivariate function {{math|{{var|f}}({{var|x}},{{var|y}}) {{=}} {{var|x}}{{sup|{{var|y}}}}}}|Exponentiation|the representation of scientific numbers|E notation}} | |||

{{Infobox mathematical function | {{Infobox mathematical function | ||

| name = Exponential | | name = Exponential | ||

| image = Image:exp.svg | | image = Image:exp.svg | ||

| imagealt = | | imagealt = Graph of the exponential function | ||

| caption = | | caption = Graph of the exponential function | ||

| general_definition = <math>\exp z = e^{z}</math> | | general_definition = <math>\exp z = e^{z}</math> | ||

| motivation_of_creation = | | motivation_of_creation = | ||

| Line 12: | Line 13: | ||

| zero = 1 | | zero = 1 | ||

| vr1 = 1 | | vr1 = 1 | ||

| f1 = ''e'' | | f1 = [[Euler's number|{{math|''e''}}]] | ||

| fixed = [[Lambert W function|{{math|−''W''{{sub|''n''}}(−1)}}]] for <math>n \in \mathbb{Z}</math> | | fixed = [[Lambert W function|{{math|−''W''{{sub|''n''}}(−1)}}]] for <math>n \in \mathbb{Z}</math> | ||

| reciprocal = <math>\exp(-z)</math> | | reciprocal = <math>\exp(-z)</math> | ||

| inverse = [[Natural logarithm]], [[Complex logarithm]] | | inverse = [[Natural logarithm]], [[Complex logarithm]] | ||

| derivative = <math>\exp' z = \exp z</math> | | derivative = <math>\exp'\! z = \exp z</math> | ||

| antiderivative = <math>\int \exp z\,dz = \exp z + C</math> | | antiderivative = <math>\int \exp z\,dz = \exp z + C</math> | ||

| taylor_series = <math>\exp z = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{z^n}{n!}</math> | | taylor_series = <math>\exp z = \sum_{n=0}^\infty\frac{z^n}{n!}</math> | ||

}} | }} | ||

[[ | In [[Mathematics|mathematics]], the '''exponential function''' is the unique [[Real function|real function]] which maps [[0|zero]] to [[1|one]] and has a [[Derivative|derivative]] everywhere equal to its value. The exponential of a variable {{tmath|x}} is denoted {{tmath|\exp x}} or {{tmath|e^x}}, with the two notations used interchangeably. It is called ''exponential'' because its argument can be seen as an exponent to which a constant [[e (mathematical constant)|number {{math|''e'' ≈ 2.718}}]], the base, is raised. There are several other definitions of the exponential function, which are all equivalent although being of very different nature. | ||

The | The exponential function converts sums to products: it maps the [[Additive identity|additive identity]] {{math|0}} to the multiplicative identity {{math|1}}, and the exponential of a sum is equal to the product of separate exponentials, {{tmath|1=\exp(x + y) = \exp x \cdot \exp y }}. Its [[Inverse function|inverse function]], the [[Natural logarithm|natural logarithm]], {{tmath|\ln}} or {{tmath|\log}}, converts products to sums: {{tmath|1= \ln(x\cdot y) = \ln x + \ln y}}. | ||

The functions | The exponential function is occasionally called the '''natural exponential function''', matching the name ''natural logarithm'', for distinguishing it from some other functions that are also commonly called ''exponential functions''. These functions include the functions of the form {{tmath|1=f(x) = b^x}}, which is [[Exponentiation|exponentiation]] with a fixed base {{tmath|b}}. More generally, and especially in applications, functions of the general form {{tmath|1=f(x) = ab^x}} are also called exponential functions. They [[Exponential growth|grow]] or [[Exponential decay|decay]] exponentially in that the rate that {{tmath|f(x)}} changes when {{tmath|x}} is increased is ''proportional'' to the current value of {{tmath|f(x)}}. | ||

The exponential function can be generalized to accept [[Complex number|complex number]]s as arguments. This reveals relations between multiplication of complex numbers, rotations in the [[Complex plane|complex plane]], and [[Trigonometry|trigonometry]]. [[Euler's formula]] {{tmath|1= \exp i\theta = \cos\theta + i\sin\theta}} expresses and summarizes these relations. | |||

The exponential function can be even further generalized to accept other types of arguments, such as matrices and elements of [[Exponential map (Lie theory)|Lie algebras]]. | |||

==Graph== | |||

The [[Graph of a function|graph]] of <math>y=e^x</math> is upward-sloping, and increases faster than every power of {{tmath|x}}.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Exponential Function Reference|url=https://www.mathsisfun.com/sets/function-exponential.html|access-date=2020-08-28|website=www.mathsisfun.com}}</ref> The graph always lies above the {{mvar|x}}-axis, but becomes arbitrarily close to it for large negative {{mvar|x}}; thus, the {{mvar|x}}-axis is a horizontal [[Asymptote|asymptote]]. The equation <math>\tfrac{d}{dx}e^x = e^x</math> means that the [[Slope|slope]] of the [[Tangent|tangent]] to the graph at each point is equal to its height (its {{mvar|y}}-coordinate) at that point. | |||

==Definitions and fundamental properties== | |||

{{see also|Characterizations of the exponential function}} | |||

There are several equivalent definitions of the exponential function, although of very different nature. | |||

===Differential equation=== | |||

[[Image:Exp tangent.svg|thumb|right |The derivative of the exponential function is equal to the value of the function. Since the derivative is the [[Slope|slope]] of the tangent, this implies that all green [[Right triangle|right triangle]]s have a base length of 1.]] | |||

The | |||

One of the simplest definitions is: The ''exponential function'' is the ''unique'' [[Differentiable function|differentiable function]] that equals its [[Derivative|derivative]], and takes the value {{math|1}} for the value {{math|0}} of its variable. | |||

The exponential function | |||

This "conceptual" definition requires a uniqueness proof and an existence proof, but it allows an easy derivation of the main properties of the exponential function. | |||

''Uniqueness: ''If {{tmath|f(x)}} and {{tmath|g(x)}} are two functions satisfying the above definition, then the derivative of {{tmath|f/g}} is zero everywhere because of the [[Quotient rule|quotient rule]]. It follows that {{tmath|f/g}} is constant; this constant is {{math|1}} since {{tmath|1=f(0) = g(0)=1}}. | |||

''Existence'' is proved in each of the two following sections. | |||

===Inverse of natural logarithm=== | |||

<math | ''The exponential function is the [[Inverse function|inverse function]] of the [[Natural logarithm|natural logarithm]].'' The [[Inverse function theorem|inverse function theorem]] implies that the natural logarithm has an inverse function, that satisfies the above definition. This is a first proof of existence. Therefore, one has | ||

:<math>\begin{align} | |||

\ln (\exp x)&=x\\ | |||

\exp(\ln y)&=y | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

for every [[Real number|real number]] <math>x</math> and every positive real number <math>y.</math> | |||

===Power series=== | |||

''The exponential function is the sum of the [[Power series|power series]]''<ref name="Rudin_1987"/><ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Weisstein| first=Eric W.|title=Exponential Function|url=https://mathworld.wolfram.com/ExponentialFunction.html|access-date=2020-08-28| website=mathworld.wolfram.com|language=en}}</ref> | |||

<math | <math display=block> | ||

\begin{align}\exp(x) &= 1+x+\frac{x^2}{2!}+ \frac{x^3}{3!}+\cdots\\ | |||

&=\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{x^n}{n!},\end{align}</math> | |||

[[Image:Exp series.gif|right|thumb|The exponential function (in blue), and the sum of the first {{math|''n'' + 1}} terms of its power series (in red)]] | |||

where <math>n!</math> is the [[Factorial|factorial]] of {{mvar|n}} (the product of the {{mvar|n}} first positive integers). This series is absolutely convergent for every <math>x</math> per the [[Ratio test|ratio test]]. So, the derivative of the sum can be computed by term-by-term differentiation, and this shows that the sum of the series satisfies the above definition. This is a second existence proof, and shows, as a byproduct, that the exponential function is defined for every {{tmath|x}}, and is everywhere the sum of its [[Maclaurin series]]. | |||

== | ===Functional equation=== | ||

''The exponential satisfies the [[Functional equation|functional equation]]:'' | |||

[[ | <math display=block>\exp(x+y)= \exp(x)\cdot \exp(y).</math> | ||

This results from the uniqueness and the fact that the function | |||

<math> f(x)=\exp(x+y)/\exp(y)</math> satisfies the above definition. | |||

It can be proved that a function that satisfies this functional equation has the form {{tmath|x \mapsto \exp(cx)}} if it is either [[Continuous function|continuous]] or [[Monotonic function|monotonic]]. It is thus [[Differentiable function|differentiable]], and equals the exponential function if its derivative at {{math|0}} is {{math|1}}. | |||

===Limit of integer powers=== | |||

''The exponential function is the [[Limit (mathematics)|limit]], as the integer {{mvar|n}} goes to infinity,<ref name="Maor"/><ref name=":0" /> | |||

<math display=block>\exp(x)=\lim_{n \to +\infty} \left(1+\frac xn\right)^n.</math> | |||

By continuity of the logarithm, this can be proved by taking logarithms and proving | |||

<math display=block>x=\lim_{n\to\infty}\ln \left(1+\frac xn\right)^n= \lim_{n\to\infty}n\ln \left(1+\frac xn\right),</math> | |||

for example with [[Taylor's theorem]]. | |||

The | ===Properties=== | ||

<math display= | ''[[Multiplicative inverse|Reciprocal]]:'' The functional equation implies {{tmath|1=e^x e^{-x}=1}}. Therefore {{tmath|e^x \ne 0}} for every {{tmath|x}} and | ||

<math display=block>\frac 1{e^x}=e^{-x}.</math> | |||

''Positiveness:'' {{tmath|e^x>0}} for every real number {{tmath|x}}. This results from the [[Intermediate value theorem|intermediate value theorem]], since {{tmath|1=e^0=1}} and, if one would have {{tmath|e^x<0}} for some {{tmath|x}}, there would be an {{tmath|y}} such that {{tmath|1=e^y=0}} between {{tmath|0}} and {{tmath|x}}. Since the exponential function equals its derivative, this implies that the exponential function is monotonically increasing. | |||

''Extension of [[Exponentiation|exponentiation]] to positive real bases:'' Let {{mvar|b}} be a positive real number. The exponential function and the natural logarithm being the inverse each of the other, one has <math>b=\exp(\ln b).</math> If {{mvar|n}} is an integer, the functional equation of the logarithm implies | |||

<math display= | <math display=block>b^n=\exp(\ln b^n)= \exp(n\ln b).</math> | ||

Since the right-most expression is defined if {{mvar|n}} is any real number, this allows defining {{tmath|b^x}} for every positive real number {{mvar|b}} and every real number {{mvar|x}}: | |||

<math display=block>b^x=\exp(x\ln b).</math> | |||

In particular, if {{mvar|b}} is the Euler's number <math>e=\exp(1),</math> one has <math>\ln e=1</math> (inverse function) and thus <math display=block>e^x=\exp(x).</math> This shows the equivalence of the two notations for the exponential function. | |||

==General exponential functions== | |||

A function is commonly called ''an exponential function''{{mdash}}with an indefinite article{{mdash}}if it has the form {{tmath|x \mapsto b^x}}, that is, if it is obtained from [[Exponentiation|exponentiation]] by fixing the base and letting the ''exponent'' vary. | |||

More generally and especially in applied contexts, the term ''exponential function'' is commonly used for functions of the form {{tmath|1=f(x) = ab^x}}. This may be motivated by the fact that, if the values of the function represent quantities, a change of measurement unit changes the value of {{tmath|a}}, and so, it is nonsensical to impose {{tmath|1=a=1}}. | |||

These most general exponential functions are the [[Differentiable function|differentiable function]]s that satisfy the following equivalent characterizations. | |||

* {{tmath|1=f(x) = ab^x}} for every {{tmath|x}} and some constants {{tmath|a}} and {{tmath|b>0}}. | |||

* {{tmath|1=f(x)=ae^{kx} }} for every {{tmath|x}} and some constants {{tmath|a}} and {{tmath|k}}. | |||

* The value of <math>f'(x)/f(x)</math> is independent of <math>x</math>. | |||

* For every <math>d,</math> the value of <math>f(x+d)/f(x)</math> is independent of <math>x;</math> that is, <math display=block>\frac{f(x+d)}{f(x)}= \frac{f(y+d)}{f(y)}</math> for every {{mvar|x}}, {{mvar|y}}.<ref>G. Harnett, ''Calculus 1'', 1998, Functions continued: | |||

"General exponential functions have the property that the ratio of two outputs depends only on the difference of inputs. The ratio of outputs for a unit change in input is the base."</ref> | |||

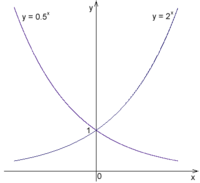

[[Image:Exponenciala priklad.png|thumb|200px|right|Exponential functions with bases 2 and 1/2]] | |||

<math display= | The ''base'' of an exponential function is the ''base'' of the [[Exponentiation|exponentiation]] that appears in it when written as {{tmath|x\to ab^x}}, namely {{tmath|b}}.<ref>G. Harnett, ''Calculus 1'', 1998; Functions continued / Exponentials & logarithms: "The ratio of outputs for a unit change in input is the ''base'' of a general exponential function."</ref> The base is {{tmath|e^k}} in the second characterization, <math display=inline>\exp \frac{f'(x)}{f(x)}</math> in the third one, and <math display=inline>\left(\frac{f(x+d)}{f(x)}\right)^{1/d}</math> in the last one. | ||

= \ | |||

The | ===In applications=== | ||

The last characterization is important in empirical sciences, as allowing a direct experimental test whether a function is an exponential function. | |||

Exponential [[Exponential growth|growth]] or [[Exponential decay|exponential decay]]{{mdash}}where the variable change is [[Proportionality (mathematics)|proportional]] to the variable value{{mdash}}are thus modeled with exponential functions. Examples are unlimited population growth leading to [[Unsolved:Malthusian catastrophe|Malthusian catastrophe]], [[Compound interest#Continuous compounding|continuously compounded interest]], and [[Physics:Radioactive decay|radioactive decay]]. | |||

If the modeling function has the form {{tmath|x\mapsto ae^{kx},}} or, equivalently, is a solution of the differential equation {{tmath|1=y'=ky}}, the constant {{tmath|k}} is called, depending on the context, the ''decay constant'', ''disintegration constant'',<ref name="Serway-Moses-Moyer_1989" /> ''rate constant'',<ref name="Simmons_1972" /> or ''transformation constant''.<ref name="McGrawHill_2007" /> | |||

===Equivalence proof=== | |||

For proving the equivalence of the above properties, one can proceed as follows. | |||

The two first characterizations are equivalent, since, if {{tmath|1=b=e^k}} and {{tmath|1= k=\ln b}}, one has | |||

<math display=block>e^{kx}= (e^k)^x= b^x.</math> | |||

The basic properties of the exponential function (derivative and functional equation) implies immediately the third and the last condition. | |||

Suppose that the third condition is verified, and let {{tmath|k}} be the constant value of <math>f'(x)/f(x).</math> Since <math display = inline>\frac {\partial e^{kx}}{\partial x}=ke^{kx},</math> the [[Quotient rule|quotient rule]] for derivation | |||

implies that | |||

<math display=block>\frac \partial{\partial x}\,\frac{f(x)}{e^{kx}}=0,</math> and thus that there is a constant {{tmath|a}} such that <math>f(x)=ae^{kx}.</math> | |||

If the last condition is verified, let <math display=inline>\varphi(d)=f(x+d)/f(x),</math> which is independent of {{tmath|x}}. Using {{tmath|1=\varphi (0)=1}}, one gets | |||

<math display= | <math display=block>\frac{f(x+d)-f(x)}{d} = f(x)\,\frac{\varphi(d)-\varphi(0)}{d}. </math> | ||

Taking the limit when {{tmath|d}} tends to zero, one gets that the third condition is verified with {{tmath|1=k=\varphi'(0)}}. It follows therefore that {{tmath|1=f(x)= ae^{kx} }} for some {{tmath|a,}} and {{tmath|1=\varphi(d)= e^{kd}.}} As a byproduct, one gets that | |||

<math display=block>\left(\frac{f(x+d)}{f(x)}\right)^{1/d}=e^k</math> | |||

is independent of both {{tmath|x}} and {{tmath|d}}. | |||

== | ==Compound interest== | ||

The | The earliest occurrence of the exponential function was in [[Biography:Jacob Bernoulli|Jacob Bernoulli]]'s study of [[Compound interest|compound interest]]s in 1683.<ref name="O'Connor_2001"/> | ||

<math display="block"> | This is this study that led Bernoulli to consider the number | ||

<math display="block">\lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1 + \frac{1}{n}\right)^{n}</math> | |||

now known as Euler's number and denoted {{tmath|e}}. | |||

The exponential function is involved as follows in the computation of [[Compound interest#Continuous compounding|continuously compounded interests]]. | |||

If a principal amount of 1 earns interest at an annual rate of {{math|''x''}} compounded monthly, then the interest earned each month is {{math|{{sfrac|''x''|12}}}} times the current value, so each month the total value is multiplied by {{math|(1 + {{sfrac|''x''|12}})}}, and the value at the end of the year is {{math|(1 + {{sfrac|''x''|12}})<sup>12</sup>}}. If instead interest is compounded daily, this becomes {{math|(1 + {{sfrac|''x''|365}})<sup>365</sup>}}. Letting the number of time intervals per year grow without bound leads to the [[Limit of a function|limit]] definition of the exponential function, | |||

<math display="block">\exp x = \lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1 + \frac{x}{n}\right)^{n}</math> | |||

first given by [[Biography:Leonhard Euler|Leonhard Euler]].<ref name="Maor"/> | |||

==Differential equations== | |||

{{main|Linear differential equation}} | |||

Exponential functions occur very often in solutions of [[Differential equation|differential equation]]s. | |||

The | The exponential functions can be defined as solutions of [[Differential equation|differential equation]]s. Indeed, the exponential function is a solution of the simplest possible differential equation, namely {{tmath|1=y'=y}}. Every other exponential function, of the form {{tmath|1=y=ab^x}}, is a solution of the differential equation {{tmath|1=y'=ky}}, and every solution of this differential equation has this form. | ||

The solutions of an equation of the form | |||

<math display= | <math display=block>y'+ky=f(x)</math> | ||

involve exponential functions in a more sophisticated way, since they have the form | |||

<math display=block>y=ce^{-kx}+e^{-kx}\int f(x)e^{kx}dx,</math> | |||

where {{tmath|c}} is an arbitrary constant and the integral denotes any [[Antiderivative|antiderivative]] of its argument. | |||

More generally, the solutions of every linear differential equation with constant coefficients can be expressed in terms of exponential functions and, when they are not homogeneous, antiderivatives. This holds true also for systems of linear differential equations with constant coefficients. | |||

The | ==Complex exponential== | ||

{{anchor|On the complex plane|Complex plane}} | |||

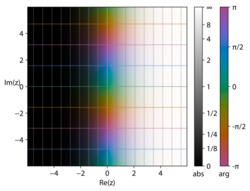

[[File:The exponential function e^z plotted in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i.svg|alt=The exponential function {{math|''e''{{isup|''z''}}}} plotted in the complex plane from {{math|−2 − 2''i''}} to {{math|2 + 2''i''}}|thumb|The exponential function {{math|''e''{{isup|''z''}}}} plotted in the complex plane from {{math|−2 − 2''i''}} to {{math|2 + 2''i''}}]] | |||

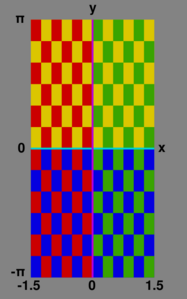

[[Image:Exp-complex-cplot.svg|thumb|right|A [[Domain coloring|complex plot]] of <math>z\mapsto\exp z</math>, with the [[Argument (complex analysis)|argument]] <math>\operatorname{Arg}\exp z</math> represented by varying hue. The transition from dark to light colors shows that <math>\left|\exp z\right|</math> is increasing only to the right. The periodic horizontal bands corresponding to the same hue indicate that <math>z\mapsto\exp z</math> is [[Periodic function|periodic]] in the imaginary part of <math>z</math>.]] | |||

The exponential function can be naturally extended to a complex function, which is a function with the [[Complex number|complex number]]s as [[Domain of a function|domain]] and [[Codomain|codomain]], such that its [[Restriction (mathematics)|restriction]] to the reals is the above-defined exponential function, called ''real exponential function'' in what follows. This function is also called ''the exponential function'', and also denoted {{tmath|e^z}} or {{tmath|\exp(z)}}. For distinguishing the complex case from the real one, the extended function is also called '''complex exponential function''' or simply '''complex exponential'''. | |||

Most of the definitions of the exponential function can be used verbatim for definiting the complex exponential function, and the proof of their equivalence is the same as in the real case. | |||

The complex exponential function can be defined in several equivalent ways that are the same as in the real case. | |||

for | The ''complex exponential'' is the unique complex function that equals its complex derivative and takes the value {{tmath|1}} for the argument {{tmath|0}}: | ||

<math display="block">\frac{de^z}{dz}=e^z\quad\text{and}\quad e^0=1.</math> | |||

The | The ''complex exponential function'' is the sum of the [[Series (mathematics)|series]] | ||

<math display="block">e^z = \sum_{k = 0}^\infty\frac{z^k}{k!}.</math> | |||

This series is absolutely convergent for every complex number {{tmath|z}}. So, the complex differential is an [[Entire function|entire function]]. | |||

The complex exponential function is the [[Limit (mathematics)|limit]] | |||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block">e^z = \lim_{n\to\infty}\left(1+\frac{z}{n}\right)^n</math> | ||

As with the real exponential function (see {{slink||Functional equation}} above), the complex exponential satisfies the functional equation | |||

<math display= | <math display=block>\exp(z+w)= \exp(z)\cdot \exp(w).</math> | ||

Among complex functions, it is the unique solution which is holomorphic at the point {{tmath|1= z = 0}} and takes the derivative {{tmath|1}} there.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hille |first=Einar |year=1959 |title=Analytic Function Theory |volume=1 |place=Waltham, MA |publisher=Blaisdell |chapter=The exponential function |at=§ 6.1, {{pgs|138–143}} }}</ref> | |||

The [[Complex logarithm|complex logarithm]] is a right-inverse function of the complex exponential: | |||

<math display="block">\ | <math display="block">e^{\log z} =z. </math> | ||

However, since the complex logarithm is a [[Multivalued function|multivalued function]], one has | |||

<math display="block">\log e^z= \{z+2ik\pi\mid k\in \Z\},</math> | |||

and it is difficult to define the complex exponential from the complex logarithm. On the opposite, this is the complex logarithm that is often defined from the complex exponential. | |||

The complex exponential | The complex exponential has the following properties: | ||

<math display="block">\frac 1{e^z}=e^{-z} </math> | |||

and | |||

<math display="block">e^z\neq 0\quad \text{for every } z\in \C .</math> | |||

It is [[Periodic function|periodic function]] of period {{tmath|2i\pi}}; that is | |||

<math display="block">e^{z+2ik\pi} =e^z \quad \text{for every } k\in \Z.</math> | |||

This results from [[Euler's identity]] {{tmath|1=e^{i\pi}=-1}} and the functional identity. | |||

The [[Complex conjugate|complex conjugate]] of the complex exponential is | |||

<math display="block">\ | <math display="block">\overline{e^z}=e^{\overline z}.</math> | ||

Its modulus is | |||

<math display="block">|e^z|= e^{\Re (z)},</math> | |||

where {{tmath|\Re(z)}} denotes the real part of {{tmath|z}}. | |||

===Relationship with trigonometry=== | |||

Complex exponential and [[Trigonometric function|trigonometric function]]s are strongly related by [[Euler's formula]]: | |||

<math display="block">e^{it} =\cos(t)+i\sin(t). </math> | |||

This formula provides the decomposition of complex exponentials into real and imaginary parts: | |||

<math display="block">e^{x+iy} = e^{x}e^{iy} = e^x\,\cos y + i e^x\,\sin y.</math> | |||

The trigonometric functions can be expressed in terms of complex exponentials: | |||

<math display="block"> | <math display="block">\begin{align} | ||

\cos x &= \frac{e^{ix}+e^{-ix}}2\\ | |||

\sin x &= \frac{e^{ix}-e^{-ix}}{2i}\\ | |||

\tan x &= i\,\frac{1-e^{2ix}}{1+e^{2ix}} | |||

\end{align}</math> | |||

In these formulas, {{tmath|x, y, t}} are commonly interpreted as real variables, but the formulas remain valid if the variables are interpreted as complex variables. These formulas may be used to define trigonometric functions of a complex variable.<ref name="Apostol_1974"/> | |||

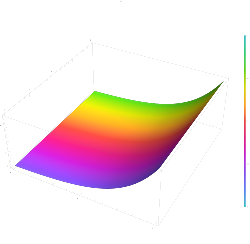

===Plots=== | |||

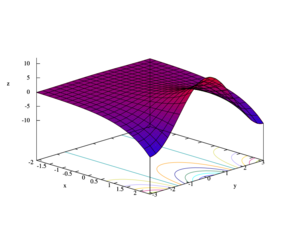

<gallery caption="3D plots of real part, imaginary part, and modulus of the exponential function" class="center" mode="packed" style="text-align:left" heights="150px"> | <gallery caption="3D plots of real part, imaginary part, and modulus of the exponential function" class="center" mode="packed" style="text-align:left" heights="150px"> | ||

Image:ExponentialAbs_real_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = Re(''e'' | Image:ExponentialAbs_real_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = Re(''e''{{isup|''x'' + ''iy''}})}} | ||

Image:ExponentialAbs_image_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = Im(''e'' | Image:ExponentialAbs_image_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = Im(''e''{{isup|''x'' + ''iy''}})}} | ||

Image:ExponentialAbs_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = {{abs|''e'' | Image:ExponentialAbs_SVG.svg| {{math|1=''z'' = {{abs|''e''{{isup|''x'' + ''iy''}}}}}} | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| Line 216: | Line 236: | ||

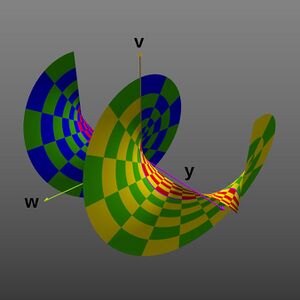

Starting with a color-coded portion of the <math>xy</math> domain, the following are depictions of the graph as variously projected into two or three dimensions. | Starting with a color-coded portion of the <math>xy</math> domain, the following are depictions of the graph as variously projected into two or three dimensions. | ||

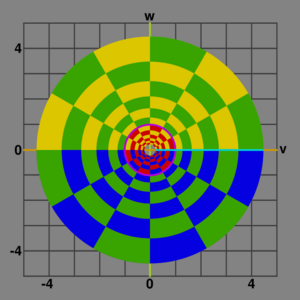

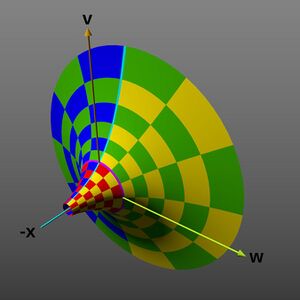

<gallery | <gallery class="center" mode="packed" style="text-align:left" heights="200px" caption="Graphs of the complex exponential function"> | ||

File: Complex exponential function graph domain xy dimensions.svg|Checker board key:<br> <math>x> 0:\; \text{green}</math><br> <math>x< 0:\; \text{red}</math><br><math> y> 0:\; \text{yellow}</math><br><math> y< 0:\; \text{blue}</math> | File: Complex exponential function graph domain xy dimensions.svg|Checker board key:<br> <math>x> 0:\; \text{green}</math><br> <math>x< 0:\; \text{red}</math><br><math>y> 0:\; \text{yellow}</math><br><math>y< 0:\; \text{blue}</math> | ||

File: Complex exponential function graph range vw dimensions.svg|Projection onto the range complex plane (V/W). Compare to the next, perspective picture. | File: Complex exponential function graph range vw dimensions.svg|Projection onto the range complex plane (V/W). Compare to the next, perspective picture. | ||

File: Complex exponential function graph horn shape xvw dimensions.jpg|Projection into the <math>x</math>, <math>v</math>, and <math>w</math> dimensions, producing a flared horn or funnel shape (envisioned as 2-D perspective image). | File: Complex exponential function graph horn shape xvw dimensions.jpg|Projection into the <math>x</math>, <math>v</math>, and <math>w</math> dimensions, producing a flared horn or funnel shape (envisioned as 2-D perspective image)|alt=Projection into the <nowiki> </nowiki> x <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle x} , <nowiki> </nowiki> v <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle v} , and <nowiki> </nowiki> w <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle w} <nowiki> </nowiki>dimensions, producing a flared horn or funnel shape (envisioned as 2-D perspective image). | ||

File: Complex exponential function graph spiral shape yvw dimensions.jpg|Projection into the <math>y</math>, <math>v</math>, and <math>w</math> dimensions, producing a spiral shape | File: Complex exponential function graph spiral shape yvw dimensions.jpg|Projection into the <math>y</math>, <math>v</math>, and <math>w</math> dimensions, producing a spiral shape (<math>y</math> range extended to ±2{{pi}}, again as 2-D perspective image)|alt=Projection into the <nowiki> </nowiki> y <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle y} , <nowiki> </nowiki> v <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle v} , and <nowiki> </nowiki> w <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle w} <nowiki> </nowiki>dimensions, producing a spiral shape. ( <nowiki> </nowiki> y <nowiki> </nowiki> {\displaystyle y} <nowiki> </nowiki>range extended to ±2π, again as 2-D perspective image). | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| Line 237: | Line 257: | ||

The fourth image shows the graph extended along the imaginary <math>y</math> axis. It shows that the graph's surface for positive and negative <math>y</math> values doesn't really meet along the negative real <math>v</math> axis, but instead forms a spiral surface about the <math>y</math> axis. Because its <math>y</math> values have been extended to {{math|±2''π''}}, this image also better depicts the 2π periodicity in the imaginary <math>y</math> value. | The fourth image shows the graph extended along the imaginary <math>y</math> axis. It shows that the graph's surface for positive and negative <math>y</math> values doesn't really meet along the negative real <math>v</math> axis, but instead forms a spiral surface about the <math>y</math> axis. Because its <math>y</math> values have been extended to {{math|±2''π''}}, this image also better depicts the 2π periodicity in the imaginary <math>y</math> value. | ||

==Matrices and Banach algebras== | ==Matrices and Banach algebras== | ||

The power series definition of the exponential function makes sense for square [[Matrix (mathematics)|matrices]] (for which the function is called the [[Matrix exponential|matrix exponential]]) and more generally in any unital [[Banach algebra]] {{math|''B''}}. In this setting, {{math|1=''e'' | The power series definition of the exponential function makes sense for square [[Matrix (mathematics)|matrices]] (for which the function is called the [[Matrix exponential|matrix exponential]]) and more generally in any unital [[Banach algebra]] {{math|''B''}}. In this setting, {{math|1=''e''{{isup|0}} = 1}}, and {{math|''e''{{isup|''x''}}}} is invertible with inverse {{math|''e''{{isup|−''x''}}}} for any {{math|''x''}} in {{math|''B''}}. If {{math|1=''xy'' = ''yx''}}, then {{math|1=''e''{{isup|''x'' + ''y''}} = ''e''{{isup|''x''}}''e''{{isup|''y''}}}}, but this identity can fail for noncommuting {{math|''x''}} and {{math|''y''}}. | ||

Some alternative definitions lead to the same function. For instance, {{math|''e'' | Some alternative definitions lead to the same function. For instance, {{math|''e''{{isup|''x''}}}} can be defined as | ||

<math display="block">\lim_{n \to \infty} \left(1 + \frac{x}{n} \right)^n .</math> | <math display="block">\lim_{n \to \infty} \left(1 + \frac{x}{n} \right)^n .</math> | ||

Or {{math|''e'' | Or {{math|''e''{{isup|''x''}}}} can be defined as {{math|''f''<sub>''x''</sub>(1)}}, where {{math|''f''<sub>''x''</sub> : '''R''' → ''B''}} is the solution to the differential equation {{math|1={{sfrac|''df''<sub>''x''</sub>|''dt''}}(''t'') = ''x{{space|hair}}f''<sub>''x''</sub>(''t'')}}, with initial condition {{math|1=''f''<sub>''x''</sub>(0) = 1}}; it follows that {{math|1=''f''<sub>''x''</sub>(''t'') = ''e''{{isup|''tx''}}}} for every {{mvar|t}} in {{math|'''R'''}}. | ||

==Lie algebras== | ==Lie algebras== | ||

| Line 259: | Line 272: | ||

==Transcendency== | ==Transcendency== | ||

The function {{math|''e'' | The function {{math|''e''{{isup|''z''}}}} is a [[Transcendental function|transcendental function]], which means that it is not a root of a polynomial over the [[Ring (mathematics)|ring]] of the rational fractions <math>\C(z).</math> | ||

If {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub>, ..., ''a''<sub>''n''</sub><nowiki/>}} are distinct complex numbers, then {{math|''e''<sup>''a''<sub>1</sub>''z''</sup>, ..., ''e''<sup>''a''<sub>''n''</sub>''z''</sup><nowiki/>}} are linearly independent over <math>\C(z)</math>, and hence {{math|''e'' | If {{math|''a''<sub>1</sub>, ..., ''a''<sub>''n''</sub><nowiki/>}} are distinct complex numbers, then {{math|''e''<sup>''a''<sub>1</sub>''z''</sup>, ..., ''e''<sup>''a''<sub>''n''</sub>''z''</sup><nowiki/>}} are linearly independent over <math>\C(z)</math>, and hence {{math|''e''{{isup|''z''}}}} is [[Transcendental function|transcendental]] over <math>\C(z)</math>. | ||

=={{anchor|exp|expm1}}Computation== | =={{anchor|exp|expm1}}Computation== | ||

The Taylor series definition above is generally efficient for computing (an approximation of) <math>e^x</math>. However, when computing near the argument <math>x=0</math>, the result will be close to 1, and computing the value of the difference <math>e^x-1</math> with [[Floating-point arithmetic|floating-point arithmetic]] may lead to the loss of (possibly all) [[Significant figures|significant figures]], producing a large relative error, possibly even a meaningless result. | |||

Following a proposal by [[Biography:William Kahan|William Kahan]], it may thus be useful to have a dedicated routine, often called <code>expm1</code>, | Following a proposal by [[Biography:William Kahan|William Kahan]], it may thus be useful to have a dedicated routine, often called <code>expm1</code>, which computes {{math|''e<sup>x</sup>'' − 1}} directly, bypassing computation of {{math|''e''{{isup|''x''}}}}. For example, | ||

one may use the Taylor series: | |||

one may use the Taylor series | |||

<math display="block">e^x-1=x+\frac {x^2}2 + \frac{x^3}6+\cdots +\frac{x^n}{n!}+\cdots.</math> | <math display="block">e^x-1=x+\frac {x^2}2 + \frac{x^3}6+\cdots +\frac{x^n}{n!}+\cdots.</math> | ||

| Line 275: | Line 287: | ||

In addition to base {{math|''e''}}, the [[IEEE 754-2008]] standard defines similar exponential functions near 0 for base 2 and 10: <math>2^x - 1</math> and <math>10^x - 1</math>. | In addition to base {{math|''e''}}, the [[IEEE 754-2008]] standard defines similar exponential functions near 0 for base 2 and 10: <math>2^x - 1</math> and <math>10^x - 1</math>. | ||

A similar approach has been used for the logarithm | A similar approach has been used for the logarithm; see log1p. | ||

An identity in terms of the hyperbolic tangent, | An identity in terms of the hyperbolic tangent, | ||

<math display="block">\operatorname{expm1} (x) = e^x - 1 = \frac{2 \tanh(x/2)}{1 - \tanh(x/2)},</math> | <math display="block">\operatorname{expm1} (x) = e^x - 1 = \frac{2 \tanh(x/2)}{1 - \tanh(x/2)},</math> | ||

gives a high-precision value for small values of {{math|''x''}} on systems that do not implement {{math|expm1(''x'')}}. | gives a high-precision value for small values of {{math|''x''}} on systems that do not implement {{math|expm1(''x'')}}. | ||

===Continued fractions=== | |||

The exponential function can also be computed with [[Continued fraction|continued fraction]]s. | |||

A continued fraction for {{math|''e''{{isup|''x''}}}} can be obtained via [[Euler's continued fraction formula|an identity of Euler]]: | |||

<math display="block"> e^x = 1 + \cfrac{x}{1 - \cfrac{x}{x + 2 - \cfrac{2x}{x + 3 - \cfrac{3x}{x + 4 - \ddots}}}}</math> | |||

The following [[Generalized continued fraction|generalized continued fraction]] for {{math|''e''{{isup|''z''}}}} also received by Euler | |||

<ref>A. N. Khovanski, The applications of continued fractions and their Generalisation to problemes in approximation theory,1963, Noordhoff, Groningen, The Netherlands</ref> | |||

converges more quickly:<ref name="Lorentzen_2008"/> | |||

<math display="block"> e^z = 1 + \cfrac{2z}{2 - z + \cfrac{z^2}{6 + \cfrac{z^2}{10 + \cfrac{z^2}{14 + \ddots}}}}</math> | |||

or, by applying the substitution {{math|1=''z'' = {{sfrac|''x''|''y''}}}}: | |||

<math display="block"> e^\frac{x}{y} = 1 + \cfrac{2x}{2y - x + \cfrac{x^2} {6y + \cfrac{x^2} {10y + \cfrac{x^2} {14y + \ddots}}}}</math> | |||

with a special case for {{math|1=''z'' = 2}}: | |||

<math display="block"> e^2 = 1 + \cfrac{4}{0 + \cfrac{2^2}{6 + \cfrac{2^2}{10 + \cfrac{2^2}{14 + \ddots }}}} = 7 + \cfrac{2}{5 + \cfrac{1}{7 + \cfrac{1}{9 + \cfrac{1}{11 + \ddots }}}}</math> | |||

This formula also converges, though more slowly, for {{math|''z'' > 2}}. For example: | |||

<math display="block"> e^3 = 1 + \cfrac{6}{-1 + \cfrac{3^2}{6 + \cfrac{3^2}{10 + \cfrac{3^2}{14 + \ddots }}}} = 13 + \cfrac{54}{7 + \cfrac{9}{14 + \cfrac{9}{18 + \cfrac{9}{22 + \ddots }}}}</math> | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 291: | Line 322: | ||

* [[List of integrals of exponential functions]] | * [[List of integrals of exponential functions]] | ||

* [[Mittag-Leffler function]], a generalization of the exponential function | * [[Mittag-Leffler function]], a generalization of the exponential function | ||

* [[ | * [[p-adic exponential function|{{math|''p''}}-adic exponential function]] | ||

* Padé table for exponential function – Padé approximation of exponential function by a fraction of polynomial functions | * Padé table for exponential function – [[Padé approximation]] of exponential function by a fraction of polynomial functions | ||

* [[Phase factor]] | |||

{{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

{{ | {{Notelist}} | ||

}} | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{ | {{reflist|refs= | ||

< | <!-- <ref name="Rudin_1976">{{Cite book |title=Principles of Mathematical Analysis |author-last=Rudin |author-first=Walter |publisher=McGraw-Hill |date=1976 |isbn=978-0-07-054235-8 |location=New York |pages=182 |url=https://archive.org/details/PrinciplesOfMathematicalAnalysis}}</ref> --> | ||

<ref name="Rudin_1976">{{Cite book |title=Principles of Mathematical Analysis |author-last=Rudin |author-first=Walter |publisher=McGraw-Hill |date=1976 |isbn=978-0-07-054235-8 |location=New York |pages=182 |url=https://archive.org/details/PrinciplesOfMathematicalAnalysis}}</ref> | |||

<ref name="Rudin_1987">{{cite book |title=Real and complex analysis |author-last=Rudin |author-first=Walter |date=1987 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=978-0-07-054234-1 |edition=3rd |location=New York |page=1 |url=https://archive.org/details/RudinW.RealAndComplexAnalysis3e1987}}</ref> | <ref name="Rudin_1987">{{cite book |title=Real and complex analysis |author-last=Rudin |author-first=Walter |date=1987 |publisher=McGraw-Hill |isbn=978-0-07-054234-1 |edition=3rd |location=New York |page=1 |url=https://archive.org/details/RudinW.RealAndComplexAnalysis3e1987}}</ref> | ||

<ref name="Maor">{{cite book |author-first=Eli |author-last=Maor |title=e: the Story of a Number |page=156}}</ref> | <ref name="Maor">{{cite book |author-first=Eli |author-last=Maor |title=e: the Story of a Number |page=156}}</ref> | ||

<ref name="O'Connor_2001">{{ | <ref name="O'Connor_2001">{{MacTutor|class=HistTopics|id=e}} | ||

</ref> | |||

<ref name="Lorentzen_2008">{{cite book |title=Continued Fractions |chapter=A.2.2 The exponential function. |author-first1=L. |author-last1=Lorentzen|author-first2=H. |author-last2=Waadeland |series=Atlantis Studies in Mathematics |date=2008 |volume=1 |doi=10.2991/978-94-91216-37-4 |page=268 |isbn=978-94-91216-37-4 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bbm%3A978-94-91216-37-4%2F1}}</ref> | <ref name="Lorentzen_2008">{{cite book |title=Continued Fractions |chapter=A.2.2 The exponential function. |author-first1=L. |author-last1=Lorentzen|author-first2=H. |author-last2=Waadeland |series=Atlantis Studies in Mathematics |date=2008 |volume=1 |doi=10.2991/978-94-91216-37-4 |page=268 |isbn=978-94-91216-37-4 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bbm%3A978-94-91216-37-4%2F1}}</ref> | ||

<ref name="Apostol_1974">{{Cite book |title=Mathematical Analysis |url=https://archive.org/details/mathematicalanal00apos_530 |url-access=limited |author-last=Apostol |author-first=Tom M. |publisher=Addison Wesley |date=1974 |isbn=978-0-201-00288-1 |edition=2nd |location=Reading, Mass. |pages=[https://archive.org/details/mathematicalanal00apos_530/page/n32 19]}}</ref> | <ref name="Apostol_1974">{{Cite book |title=Mathematical Analysis |url=https://archive.org/details/mathematicalanal00apos_530 |url-access=limited |author-last=Apostol |author-first=Tom M. |publisher=Addison Wesley |date=1974 |isbn=978-0-201-00288-1 |edition=2nd |location=Reading, Mass. |pages=[https://archive.org/details/mathematicalanal00apos_530/page/n32 19]}}</ref> | ||

Latest revision as of 19:52, 14 February 2026

Template:Infobox mathematical function

In mathematics, the exponential function is the unique real function which maps zero to one and has a derivative everywhere equal to its value. The exponential of a variable is denoted or , with the two notations used interchangeably. It is called exponential because its argument can be seen as an exponent to which a constant number e ≈ 2.718, the base, is raised. There are several other definitions of the exponential function, which are all equivalent although being of very different nature.

The exponential function converts sums to products: it maps the additive identity 0 to the multiplicative identity 1, and the exponential of a sum is equal to the product of separate exponentials, . Its inverse function, the natural logarithm, or , converts products to sums: .

The exponential function is occasionally called the natural exponential function, matching the name natural logarithm, for distinguishing it from some other functions that are also commonly called exponential functions. These functions include the functions of the form , which is exponentiation with a fixed base . More generally, and especially in applications, functions of the general form are also called exponential functions. They grow or decay exponentially in that the rate that changes when is increased is proportional to the current value of .

The exponential function can be generalized to accept complex numbers as arguments. This reveals relations between multiplication of complex numbers, rotations in the complex plane, and trigonometry. Euler's formula expresses and summarizes these relations.

The exponential function can be even further generalized to accept other types of arguments, such as matrices and elements of Lie algebras.

Graph

The graph of is upward-sloping, and increases faster than every power of .[1] The graph always lies above the x-axis, but becomes arbitrarily close to it for large negative x; thus, the x-axis is a horizontal asymptote. The equation means that the slope of the tangent to the graph at each point is equal to its height (its y-coordinate) at that point.

Definitions and fundamental properties

There are several equivalent definitions of the exponential function, although of very different nature.

Differential equation

One of the simplest definitions is: The exponential function is the unique differentiable function that equals its derivative, and takes the value 1 for the value 0 of its variable.

This "conceptual" definition requires a uniqueness proof and an existence proof, but it allows an easy derivation of the main properties of the exponential function.

Uniqueness: If and are two functions satisfying the above definition, then the derivative of is zero everywhere because of the quotient rule. It follows that is constant; this constant is 1 since .

Existence is proved in each of the two following sections.

Inverse of natural logarithm

The exponential function is the inverse function of the natural logarithm. The inverse function theorem implies that the natural logarithm has an inverse function, that satisfies the above definition. This is a first proof of existence. Therefore, one has

for every real number and every positive real number

Power series

The exponential function is the sum of the power series[2][3]

where is the factorial of n (the product of the n first positive integers). This series is absolutely convergent for every per the ratio test. So, the derivative of the sum can be computed by term-by-term differentiation, and this shows that the sum of the series satisfies the above definition. This is a second existence proof, and shows, as a byproduct, that the exponential function is defined for every , and is everywhere the sum of its Maclaurin series.

Functional equation

The exponential satisfies the functional equation: This results from the uniqueness and the fact that the function satisfies the above definition.

It can be proved that a function that satisfies this functional equation has the form if it is either continuous or monotonic. It is thus differentiable, and equals the exponential function if its derivative at 0 is 1.

Limit of integer powers

The exponential function is the limit, as the integer n goes to infinity,[4][3] By continuity of the logarithm, this can be proved by taking logarithms and proving for example with Taylor's theorem.

Properties

Reciprocal: The functional equation implies . Therefore for every and

Positiveness: for every real number . This results from the intermediate value theorem, since and, if one would have for some , there would be an such that between and . Since the exponential function equals its derivative, this implies that the exponential function is monotonically increasing.

Extension of exponentiation to positive real bases: Let b be a positive real number. The exponential function and the natural logarithm being the inverse each of the other, one has If n is an integer, the functional equation of the logarithm implies Since the right-most expression is defined if n is any real number, this allows defining for every positive real number b and every real number x: In particular, if b is the Euler's number one has (inverse function) and thus This shows the equivalence of the two notations for the exponential function.

General exponential functions

A function is commonly called an exponential function—with an indefinite article—if it has the form , that is, if it is obtained from exponentiation by fixing the base and letting the exponent vary.

More generally and especially in applied contexts, the term exponential function is commonly used for functions of the form . This may be motivated by the fact that, if the values of the function represent quantities, a change of measurement unit changes the value of , and so, it is nonsensical to impose .

These most general exponential functions are the differentiable functions that satisfy the following equivalent characterizations.

- for every and some constants and .

- for every and some constants and .

- The value of is independent of .

- For every the value of is independent of that is, for every x, y.[5]

The base of an exponential function is the base of the exponentiation that appears in it when written as , namely .[6] The base is in the second characterization, in the third one, and in the last one.

In applications

The last characterization is important in empirical sciences, as allowing a direct experimental test whether a function is an exponential function.

Exponential growth or exponential decay—where the variable change is proportional to the variable value—are thus modeled with exponential functions. Examples are unlimited population growth leading to Malthusian catastrophe, continuously compounded interest, and radioactive decay.

If the modeling function has the form or, equivalently, is a solution of the differential equation , the constant is called, depending on the context, the decay constant, disintegration constant,[7] rate constant,[8] or transformation constant.[9]

Equivalence proof

For proving the equivalence of the above properties, one can proceed as follows.

The two first characterizations are equivalent, since, if and , one has The basic properties of the exponential function (derivative and functional equation) implies immediately the third and the last condition.

Suppose that the third condition is verified, and let be the constant value of Since the quotient rule for derivation implies that and thus that there is a constant such that

If the last condition is verified, let which is independent of . Using , one gets Taking the limit when tends to zero, one gets that the third condition is verified with . It follows therefore that for some and As a byproduct, one gets that is independent of both and .

Compound interest

The earliest occurrence of the exponential function was in Jacob Bernoulli's study of compound interests in 1683.[10] This is this study that led Bernoulli to consider the number now known as Euler's number and denoted .

The exponential function is involved as follows in the computation of continuously compounded interests.

If a principal amount of 1 earns interest at an annual rate of x compounded monthly, then the interest earned each month is x/12 times the current value, so each month the total value is multiplied by (1 + x/12), and the value at the end of the year is (1 + x/12)12. If instead interest is compounded daily, this becomes (1 + x/365)365. Letting the number of time intervals per year grow without bound leads to the limit definition of the exponential function, first given by Leonhard Euler.[4]

Differential equations

Exponential functions occur very often in solutions of differential equations.

The exponential functions can be defined as solutions of differential equations. Indeed, the exponential function is a solution of the simplest possible differential equation, namely . Every other exponential function, of the form , is a solution of the differential equation , and every solution of this differential equation has this form.

The solutions of an equation of the form involve exponential functions in a more sophisticated way, since they have the form where is an arbitrary constant and the integral denotes any antiderivative of its argument.

More generally, the solutions of every linear differential equation with constant coefficients can be expressed in terms of exponential functions and, when they are not homogeneous, antiderivatives. This holds true also for systems of linear differential equations with constant coefficients.

Complex exponential

The exponential function can be naturally extended to a complex function, which is a function with the complex numbers as domain and codomain, such that its restriction to the reals is the above-defined exponential function, called real exponential function in what follows. This function is also called the exponential function, and also denoted or . For distinguishing the complex case from the real one, the extended function is also called complex exponential function or simply complex exponential.

Most of the definitions of the exponential function can be used verbatim for definiting the complex exponential function, and the proof of their equivalence is the same as in the real case.

The complex exponential function can be defined in several equivalent ways that are the same as in the real case.

The complex exponential is the unique complex function that equals its complex derivative and takes the value for the argument :

The complex exponential function is the sum of the series This series is absolutely convergent for every complex number . So, the complex differential is an entire function.

The complex exponential function is the limit

As with the real exponential function (see § Functional equation above), the complex exponential satisfies the functional equation Among complex functions, it is the unique solution which is holomorphic at the point and takes the derivative there.[11]

The complex logarithm is a right-inverse function of the complex exponential: However, since the complex logarithm is a multivalued function, one has and it is difficult to define the complex exponential from the complex logarithm. On the opposite, this is the complex logarithm that is often defined from the complex exponential.

The complex exponential has the following properties: and It is periodic function of period ; that is This results from Euler's identity and the functional identity.

The complex conjugate of the complex exponential is Its modulus is where denotes the real part of .

Relationship with trigonometry

Complex exponential and trigonometric functions are strongly related by Euler's formula:

This formula provides the decomposition of complex exponentials into real and imaginary parts:

The trigonometric functions can be expressed in terms of complex exponentials:

In these formulas, are commonly interpreted as real variables, but the formulas remain valid if the variables are interpreted as complex variables. These formulas may be used to define trigonometric functions of a complex variable.[12]

Plots

- 3D plots of real part, imaginary part, and modulus of the exponential function

-

z = Re(ex + iy)

-

z = Im(ex + iy)

-

z = |ex + iy|

Considering the complex exponential function as a function involving four real variables: the graph of the exponential function is a two-dimensional surface curving through four dimensions.

Starting with a color-coded portion of the domain, the following are depictions of the graph as variously projected into two or three dimensions.

- Graphs of the complex exponential function

-

Checker board key:

-

Projection onto the range complex plane (V/W). Compare to the next, perspective picture.

-

Projection into the , , and dimensions, producing a flared horn or funnel shape (envisioned as 2-D perspective image)

-

Projection into the , , and dimensions, producing a spiral shape ( range extended to ±2π, again as 2-D perspective image)

The second image shows how the domain complex plane is mapped into the range complex plane:

- zero is mapped to 1

- the real axis is mapped to the positive real axis

- the imaginary axis is wrapped around the unit circle at a constant angular rate

- values with negative real parts are mapped inside the unit circle

- values with positive real parts are mapped outside of the unit circle

- values with a constant real part are mapped to circles centered at zero

- values with a constant imaginary part are mapped to rays extending from zero

The third and fourth images show how the graph in the second image extends into one of the other two dimensions not shown in the second image.

The third image shows the graph extended along the real axis. It shows the graph is a surface of revolution about the axis of the graph of the real exponential function, producing a horn or funnel shape.

The fourth image shows the graph extended along the imaginary axis. It shows that the graph's surface for positive and negative values doesn't really meet along the negative real axis, but instead forms a spiral surface about the axis. Because its values have been extended to ±2π, this image also better depicts the 2π periodicity in the imaginary value.

Matrices and Banach algebras

The power series definition of the exponential function makes sense for square matrices (for which the function is called the matrix exponential) and more generally in any unital Banach algebra B. In this setting, e0 = 1, and ex is invertible with inverse e−x for any x in B. If xy = yx, then ex + y = exey, but this identity can fail for noncommuting x and y.

Some alternative definitions lead to the same function. For instance, ex can be defined as

Or ex can be defined as fx(1), where fx : R → B is the solution to the differential equation dfx/dt(t) = x fx(t), with initial condition fx(0) = 1; it follows that fx(t) = etx for every t in R.

Lie algebras

Given a Lie group G and its associated Lie algebra , the exponential map is a map ↦ G satisfying similar properties. In fact, since R is the Lie algebra of the Lie group of all positive real numbers under multiplication, the ordinary exponential function for real arguments is a special case of the Lie algebra situation. Similarly, since the Lie group GL(n,R) of invertible n × n matrices has as Lie algebra M(n,R), the space of all n × n matrices, the exponential function for square matrices is a special case of the Lie algebra exponential map.

The identity can fail for Lie algebra elements x and y that do not commute; the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula supplies the necessary correction terms.

Transcendency

The function ez is a transcendental function, which means that it is not a root of a polynomial over the ring of the rational fractions

If a1, ..., an are distinct complex numbers, then ea1z, ..., eanz are linearly independent over , and hence ez is transcendental over .

Computation

The Taylor series definition above is generally efficient for computing (an approximation of) . However, when computing near the argument , the result will be close to 1, and computing the value of the difference with floating-point arithmetic may lead to the loss of (possibly all) significant figures, producing a large relative error, possibly even a meaningless result.

Following a proposal by William Kahan, it may thus be useful to have a dedicated routine, often called expm1, which computes ex − 1 directly, bypassing computation of ex. For example,

one may use the Taylor series:

This was first implemented in 1979 in the Hewlett-Packard HP-41C calculator, and provided by several calculators,[13][14] operating systems (for example Berkeley UNIX 4.3BSD[15]), computer algebra systems, and programming languages (for example C99).[16]

In addition to base e, the IEEE 754-2008 standard defines similar exponential functions near 0 for base 2 and 10: and .

A similar approach has been used for the logarithm; see log1p.

An identity in terms of the hyperbolic tangent, gives a high-precision value for small values of x on systems that do not implement expm1(x).

Continued fractions

The exponential function can also be computed with continued fractions.

A continued fraction for ex can be obtained via an identity of Euler:

The following generalized continued fraction for ez also received by Euler [17] converges more quickly:[18]

or, by applying the substitution z = x/y: with a special case for z = 2:

This formula also converges, though more slowly, for z > 2. For example:

See also

- Carlitz exponential, a characteristic p analogue

- Double exponential function – Exponential function of an exponential function

- Exponential field – Mathematical field with an extra operation

- Gaussian function

- Half-exponential function, a compositional square root of an exponential function

- List of exponential topics

- List of integrals of exponential functions

- Mittag-Leffler function, a generalization of the exponential function

- p-adic exponential function

- Padé table for exponential function – Padé approximation of exponential function by a fraction of polynomial functions

- Phase factor

Notes

References

- ↑ "Exponential Function Reference". https://www.mathsisfun.com/sets/function-exponential.html.

- ↑ Real and complex analysis (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 1987. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-07-054234-1. https://archive.org/details/RudinW.RealAndComplexAnalysis3e1987.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weisstein, Eric W.. "Exponential Function" (in en). https://mathworld.wolfram.com/ExponentialFunction.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 e: the Story of a Number. p. 156.

- ↑ G. Harnett, Calculus 1, 1998, Functions continued: "General exponential functions have the property that the ratio of two outputs depends only on the difference of inputs. The ratio of outputs for a unit change in input is the base."

- ↑ G. Harnett, Calculus 1, 1998; Functions continued / Exponentials & logarithms: "The ratio of outputs for a unit change in input is the base of a general exponential function."

- ↑ Serway, Raymond A.; Moses, Clement J.; Moyer, Curt A. (1989). Modern Physics. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 384. ISBN 0-03-004844-3.

- ↑ Simmons, George F. (1972). Differential Equations with Applications and Historical Notes. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 15.

- ↑ "McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology". McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2007. ISBN 978-0-07-144143-8.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Exponential function", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/e.html.

- ↑ Hille, Einar (1959). "The exponential function". Analytic Function Theory. 1. Waltham, MA: Blaisdell. § 6.1, Template:Pgs.

- ↑ Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.). Reading, Mass.: Addison Wesley. 1974. pp. 19. ISBN 978-0-201-00288-1. https://archive.org/details/mathematicalanal00apos_530.

- ↑ HP 48G Series – Advanced User's Reference Manual (AUR) (4 ed.). Hewlett-Packard. December 1994. HP 00048-90136, 0-88698-01574-2. http://www.hpcalc.org/details.php?id=6036. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- ↑ HP 50g / 49g+ / 48gII graphing calculator advanced user's reference manual (AUR) (2 ed.). Hewlett-Packard. 2009-07-14. HP F2228-90010. http://www.hpcalc.org/details.php?id=7141. Retrieved 2015-10-10. [1]

- ↑ "Chapter 10.2. Exponential near zero". The Mathematical-Function Computation Handbook - Programming Using the MathCW Portable Software Library (1 ed.). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Springer International Publishing AG. 2017-08-22. pp. 273–282. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64110-2. ISBN 978-3-319-64109-6. "Berkeley UNIX 4.3BSD introduced the expm1() function in 1987."

- ↑ "Computation of expm1 = exp(x)−1". Salt Lake City, Utah, USA: Department of Mathematics, Center for Scientific Computing, University of Utah. 2002-07-09. http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/reports/expm1.pdf.

- ↑ A. N. Khovanski, The applications of continued fractions and their Generalisation to problemes in approximation theory,1963, Noordhoff, Groningen, The Netherlands

- ↑ "A.2.2 The exponential function.". Continued Fractions. Atlantis Studies in Mathematics. 1. 2008. p. 268. doi:10.2991/978-94-91216-37-4. ISBN 978-94-91216-37-4. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/bbm%3A978-94-91216-37-4%2F1.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Exponential function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/e036910

|