Medicine:Cluster headache

| Cluster headache | |

|---|---|

| |

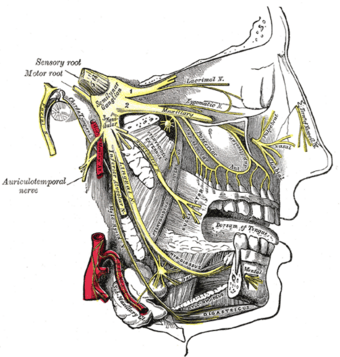

| Trigeminal nerve | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Recurrent, severe headaches on one side of the head, eye watering, stuffy nose[1] |

| Usual onset | 20 to 40 years old[2] |

| Duration | 15 min to 3 hrs[2] |

| Types | Episodic, chronic[2] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Risk factors | Tobacco smoke, family history[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Migraine, trigeminal neuralgia,[2] other trigeminal autonomic cephalgias[3] |

| Prevention | Verapamil, galcanezumab, oral glucocorticoids, steroid injections, civamide,[4] |

| Treatment | Oxygen therapy, triptans[2][4] |

| Frequency | ~0.1% at some point in time[5] |

Cluster headache (CH) is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent severe headaches on one side of the head, typically around the eye(s).[1] There is often accompanying eye watering, nasal congestion, or swelling around the eye on the affected side.[1] These symptoms typically last 15 minutes to 3 hours.[2] Attacks often occur in clusters which typically last for weeks or months and occasionally more than a year.[2]

The cause is unknown,[2] but is most likely related to dysfunction of the posterior hypothalamus.[6] Risk factors include a history of exposure to tobacco smoke and a family history of the condition.[2] Exposures which may trigger attacks include alcohol, nitroglycerin, and histamine.[2] They are a primary headache disorder of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias type.[2] Diagnosis is based on symptoms.[2]

Recommended management includes lifestyle adaptations such as avoiding potential triggers.[2] Treatments for acute attacks include oxygen or a fast-acting triptan.[2][4] Measures recommended to decrease the frequency of attacks include steroid injections, galcanezumab, civamide, verapamil, or oral glucocorticoids such as prednisone.[6][4][7] Nerve stimulation or surgery may occasionally be used if other measures are not effective.[2][6]

The condition affects about 0.1% of the general population at some point in their life and 0.05% in any given year.[5] The condition usually first occurs between 20 and 40 years of age.[2] Men are affected about four times more often than women.[5] Cluster headaches are named for the occurrence of groups of headache attacks (clusters).[1] They have also been referred to as "suicide headaches".[2]

Signs and symptoms

Cluster headaches are recurring bouts of severe unilateral headache attacks.[8][9] The duration of a typical CH attack ranges from about 15 to 180 minutes.[2] About 75% of untreated attacks last less than 60 minutes.[10] However, women may have longer and more severe CH.[11]

The onset of an attack is rapid and typically without an aura. Preliminary sensations of pain in the general area of attack, referred to as "shadows", may signal an imminent CH, or these symptoms may linger after an attack has passed, or between attacks.[12] Though CH is strictly unilateral, there are some documented cases of "side-shift" between cluster periods,[13] or, rarely, simultaneous (within the same cluster period) bilateral cluster headaches.[14]

Pain

The pain occurs only on one side of the head, around the eye, particularly behind or above the eye, in the temple. The pain is typically greater than in other headache conditions, including migraines, and is usually described as burning, stabbing, drilling or squeezing.[15] While suicide is rare, those with cluster headaches may experience suicidal thoughts (giving the alternative name "suicide headache" or "suicidal headache").[16][17] The term "headache" does not adequately convey the severity of the condition; the disease may be the most painful condition known to medical science.[18][19]

Dr. Peter Goadsby, Professor of Clinical Neurology at University College London, a leading researcher on the condition has commented:

"Cluster headache is probably the worst pain that humans experience. I know that's quite a strong remark to make, but if you ask a cluster headache patient if they've had a worse experience, they'll universally say they haven't. Women with cluster headache will tell you that an attack is worse than giving birth. So you can imagine that these people give birth without anesthetic once or twice a day, for six, eight, or ten weeks at a time, and then have a break. It's just awful."[20]

Other symptoms

The typical symptoms of cluster headache include grouped occurrence and recurrence (cluster) of headache attack, severe unilateral orbital, supraorbital and/or temporal pain. If left untreated, attack frequency may range from one attack every two days to eight attacks per day.[2][21] Cluster headache attack is accompanied by at least one of the following autonomic symptoms: drooping eyelid, pupil constriction, redness of the conjunctiva, tearing, runny nose and less commonly, facial blushing, swelling, or sweating, typically appearing on the same side of the head as the pain.[21] Similar to a migraine, sensitivity to light (photophobia) or noise (phonophobia) may occur during a CH. Nausea is a rare symptom although it has been reported.[8]

Restlessness (for example, pacing or rocking back and forth) may occur. Secondary effects may include the inability to organize thoughts and plans, physical exhaustion, confusion, agitation, aggressiveness, depression, and anxiety.[16]

People with CH may dread facing another headache and adjust their physical or social activities around a possible future occurrence. Likewise they may seek assistance to accomplish what would otherwise be normal tasks. They may hesitate to make plans because of the regularity, or conversely, the unpredictability of the pain schedule. These factors can lead to generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorder,[16] serious depressive disorders,[22] social withdrawal and isolation.[23]

Cluster headaches have been recently associated with obstructive sleep apnea comorbidity.[24]

Recurrence

Cluster headaches may occasionally be referred to as "alarm clock headache" because of the regularity of their recurrence. CH attacks often awaken individuals from sleep. Both individual attacks and the cluster grouping can have a metronomic regularity; attacks typically striking at a precise time of day each morning or night. The recurrence of headache cluster grouping may occur more often around solstices, or seasonal changes, sometimes showing circannual periodicity. Conversely, attack frequency may be highly unpredictable, showing no periodicity at all. These observations have prompted researchers to speculate an involvement or dysfunction of the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus controls the body's "biological clock" and circadian rhythm.[25][26] In episodic cluster headache, attacks occur once or more daily, often at the same time each day for a period of several weeks, followed by a headache-free period lasting weeks, months, or years. Approximately 10–15% of cluster headaches are chronic, with multiple headaches occurring every day for years, sometimes without any remission.[27]

In accordance with the International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria, cluster headaches occurring in two or more cluster periods, lasting from 7 to 365 days with a pain-free remission of one month or longer between the headache attacks may be classified as episodic. If headache attacks occur for more than a year without pain-free remission of at least one month, the condition is classified as chronic.[21] Chronic CH both occurs and recurs without any remission periods between cycles; there may be variation in cycles, meaning the frequency and severity of attacks may change without predictability for a period of time. The frequency, severity, and duration of headache attacks experienced by people during these cycles varies between individuals and does not demonstrate complete remission of the episodic form. The condition may change unpredictably from chronic to episodic and from episodic to chronic.[28]

Causes

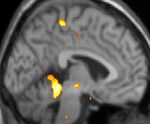

| 150x150px | ||

| Positron emission tomography (PET) shows brain areas being activated during pain. | ||

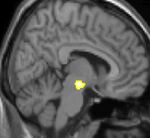

| 150x150px | ||

| Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) shows brain area structural differences. | ||

The specific causes and pathogenesis of cluster headaches are not fully understood.[6] The Third Edition of the International Classification of Headache disorders classifies CH as belonging to the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.[29]

Some experts consider the posterior hypothalamus to be important in the pathogenesis of cluster headaches. This is supported by a relatively high success ratio of deep-brain stimulation therapy on the posterior hypothalamic grey matter.[6]

Nerves

Therapies acting on the vagus nerve (CN X) and the greater occipital nerve have both shown efficacy in managing cluster headache, but the specific roles of these nerves are not well-understood.[6] Two nerves thought to play an important role in CH include the trigeminal nerve and the facial nerve.[30]

Genetics

Cluster headache may run in some families in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.[31][32] People with a first degree relative with the condition are about 14–48 times more likely to develop it themselves,[1] and around 8 to 10% of persons with CH have a positive family history.[31][33] Several studies have found a higher number of relatives affected among females.[33] Others have suggested these observations may be due to lower numbers of females in these studies.[33] Possible genetic factors warrant further research, current evidence for genetic inheritance is limited.[32]

Genes that are thought to play a role in the disease are the hypocretin/orexin receptor type 2 (HCRTR2), alcohol dehydrogenase 4(ADH4), G protein beta 3 (GNB3), pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide type I receptor (ADCYAP1R1), and membrane metalloendopeptidase (MME) genes.[31]

Tobacco smoking

About 65% of persons with CH are, or have been, tobacco smokers.[1] Stopping smoking does not lead to improvement of the condition and CH also occurs in those who have never smoked (e.g. children);[1] it is thought unlikely that smoking is a cause.[1] People with CH may be predisposed to certain traits, including smoking or other lifestyle habits.[34]

Hypothalamus

A review suggests that the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, which is the major biological clock in the human body, may be involved in cluster headaches, because CH occurs with diurnal and seasonal rhythmicity.[35]

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans indicate the brain areas which are activated during attack only, compared to pain free periods. These pictures show brain areas that are active during pain in yellow/orange color (called "pain matrix"). The area in the center (in all three views) is specifically activated during CH only. The bottom row voxel-based morphometry (VBM) shows structural brain differences between individuals with and without CH; only a portion of the hypothalamus is different.[36]

Diagnosis

Cluster-like head pain may be diagnosed as secondary headache rather than cluster headache.[21]

A detailed oral history aids practitioners in correct differential diagnosis, as there are no confirmatory tests for CH. A headache diary can be useful in tracking when and where pain occurs, how severe it is, and how long the pain lasts. A record of coping strategies used may help distinguish between headache type; data on frequency, severity and duration of headache attacks are a necessary tool for initial and correct differential diagnosis in headache conditions.[37]

Correct diagnosis presents a challenge as the first CH attack may present where staff are not trained in the diagnosis of rare or complex chronic disease.[10] Experienced ER staff are sometimes trained to detect headache types.[38] While CH attacks themselves are not directly life-threatening, suicide ideation has been observed.[16]

Individuals with CH typically experience diagnostic delay before correct diagnosis.[39] People are often misdiagnosed due to reported neck, tooth, jaw, and sinus symptoms and may unnecessarily endure many years of referral to ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialists for investigation of sinuses; dentists for tooth assessment; chiropractors and manipulative therapists for treatment; or psychiatrists, psychologists, and other medical disciplines before their headaches are correctly diagnosed.[40] Under-recognition of CH by health care professionals is reflected in consistent findings in Europe and the United States that the average time to diagnosis is around seven years.[41]

Differential

Cluster headache may be misdiagnosed as migraine or sinusitis.[41] Other types of headache are sometimes mistaken for, or may mimic closely, CH. Incorrect terms like "cluster migraine" confuse headache types, confound differential diagnosis and are often the cause of unnecessary diagnostic delay,[42] ultimately delaying appropriate specialist treatment.

Headaches that may be confused with CH include:

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania (CPH) is a unilateral headache condition, without the male predominance usually seen in CH. Paroxysmal hemicrania may also be episodic but the episodes of pain seen in CPH are usually shorter than those seen with cluster headaches. CPH typically responds "absolutely" to treatment with the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin[21] where in most cases CH typically shows no positive indomethacin response, making "Indomethacin response" an important diagnostic tool for specialist practitioners seeking correct differential diagnosis between the conditions.[43][44]

- Hemicrania continua[45]

- Short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) is a headache syndrome belonging to the group of TACs.[21][46]

- Trigeminal neuralgia is a unilateral headache syndrome,[40] or "cluster-like" headache.[47]

Prevention

Management for cluster headache is divided into three primary categories: abortive, transitional, and preventive.[48] Preventive treatments are used to reduce or eliminate cluster headache attacks; they are generally used in combination with abortive and transitional techniques.[8]

Verapamil

The recommended first-line preventive therapy is verapamil, a calcium channel blocker.[2][49] Verapamil was previously underused in people with cluster headache.[8] Improvement can be seen in an average of 1.7 weeks for episodic CH and 5 weeks for chronic CH when using a dosage of ranged between 160 and 720 mg (mean 240 mg/day).[50] Preventive therapy with verapamil is believed to work because it has an effect on the circadian rhythm and on CGRPs. As CGRP-release is controlled by voltage-gated calcium channels.[50]

Glucocorticoids

Since these compounds are steroids, there is little evidence to support long-term benefits from glucocorticoids,[2] but they may be used until other medications take effect as they appear to be effective at three days.[2] They are generally discontinued after 8–10 days of treatment.[8] Prednisone is given at a starting dose of 60–80 milligrams daily; then it is reduced by 5 milligrams every day. Corticosteroids are also used to break cycles, especially in chronic patients.[51]

Surgery

Nerve stimulators may be an option in the small number of people who do not improve with medications.[52][53] Two procedures, deep brain stimulation or occipital nerve stimulation, may be useful;[2] early experience shows a benefit in about 60% of cases.[54] It typically takes weeks or months for this benefit to appear.[53] A non-invasive method using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is being studied.[53]

A number of surgical procedures, such as a rhizotomy or microvascular decompression, may also be considered,[53] but evidence to support them is limited and there are cases of people whose symptoms worsen after these procedures.[53]

Other

Lithium, methysergide, and topiramate are recommended alternative treatments,[49][55] although there is little evidence supporting the use of topiramate or methysergide.[2][56] This is also true for tianeptine, melatonin, and ergotamine.[2] Valproate, sumatriptan, and oxygen are not recommended as preventive measures.[2] Botulinum toxin injections have shown limited success.[57] Evidence for baclofen, botulinum toxin, and capsaicin is unclear.[56]

Management

There are two primary treatments for acute CH: oxygen and triptans,[2] but they are underused due to misdiagnosis of the syndrome.[8] During bouts of headaches, triggers such as alcohol, nitroglycerine, and naps during the day should be avoided.[10]

Oxygen

Oxygen therapy may help to abort attacks, though it does not prevent future episodes.[2] Typically it is given via a non-rebreather mask at 12–15 liters per minute for 15–20 minutes.[2] One review found about 70% of patients improve within 15 minutes.[10] The evidence for effectiveness of 100% oxygen, however, is weak.[10][58] Hyperbaric oxygen at pressures of ~2 times greater than atmospheric pressure may relieve cluster headaches.[58]

Triptans

The other primarily recommended treatment of acute attacks is subcutaneous or intranasal sumatriptan.[49][59] Sumatriptan and zolmitriptan have both been shown to improve symptoms during an attack with sumatriptan being superior.[60] Because of the vasoconstrictive side-effect of triptans, they may be contraindicated in people with ischemic heart disease.[2] The vasoconstrictor ergot compounds may be useful,[10] but have not been well studied in acute attacks.[60]

Opioids

The use of opioid medication in management of CH is not recommended[61] and may make headache syndromes worse.[62][63] Long-term opioid use is associated with well known dependency, addiction, and withdrawal syndromes.[64] Prescription of opioid medication may additionally lead to further delay in differential diagnosis, undertreatment, and mismanagement.[61]

Other

Intranasal lidocaine (sprayed in the ipsilateral nostril) may be an effective treatment with patient resistant to more conventional treatment.[11]

Octreotide administered subcutaneously has been demonstrated to be more effective than placebo for the treatment of acute attacks.[65]

Sub-occipital steroid injections have shown benefit and are recommended for use as a transitional therapy to provide temporary headache relief as more long term prophylactic therapies are instituted.[66]

Epidemiology

Cluster headache affects about 0.1% of the general population at some point in their life.[5] Males are affected about four times more often than females.[5] The condition usually starts between the ages of 20 and 50 years, although it can occur at any age.[1] About one in five of adults reports the onset of cluster headache between 10 and 19 years.[67]

History

The first complete description of cluster headache was given by the London neurologist Wilfred Harris in 1926, who named the disease migrainous neuralgia.[68][69][70] Descriptions of CH date to 1745 and probably earlier.[71]

The condition was originally named Horton's cephalalgia after Bayard Taylor Horton, a US neurologist who postulated the first theory as to their pathogenesis. His original paper describes the severity of the headaches as being able to take normal men and force them to attempt or die by suicide; his 1939 paper said:

"Our patients were disabled by the disorder and suffered from bouts of pain from two to twenty times a week. They had found no relief from the usual methods of treatment. Their pain was so severe that several of them had to be constantly watched for fear of suicide. Most of them were willing to submit to any operation which might bring relief."[72]

CH has alternately been called erythroprosopalgia of Bing, ciliary neuralgia, erythromelalgia of the head, Horton's headache, histaminic cephalalgia, petrosal neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, vidian neuralgia, Sluder's neuralgia, Sluder's syndrome, and hemicrania angioparalyticia.[73]

Society and culture

Robert Shapiro, a professor of neurology, says that while cluster headaches are about as common as multiple sclerosis with a similar disability level, as of 2013, the US National Institutes of Health had spent $1.872 billion on research into multiple sclerosis in one decade, but less than $2 million on CH research in 25 years.[74]

Research directions

Some case reports suggest that ingesting tryptamines such as LSD, psilocybin (as found in hallucinogenic mushrooms), or DMT can abort attacks and interrupt cluster headache cycles.[75][76] The hallucinogen DMT has a chemical structure that is similar to the triptan sumatriptan, indicating a possible shared mechanism in preventing or stopping migraine and TACs.[51] In a 2006 survey of 53 individuals, 18 of 19 psilocybin users reported extended remission periods. The survey was not a blinded or a controlled study, and was "limited by recall and selection bias".[75] The safety and efficacy of psilocybin is currently being studied in cluster headache.[77][78]

Fremanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against calcitonin gene-related peptides alpha and beta, was in phase 3 clinical trials for CH, but stopped early due to a futility analysis demonstrating that a successful outcome was unlikely.[79][80]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Nesbitt, A. D.; Goadsby, P. J. (2012). "Cluster headache". BMJ 344: e2407. doi:10.1136/bmj.e2407. PMID 22496300.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 Weaver-Agostoni, J (2013). "Cluster headache". American Family Physician 88 (2): 122–8. PMID 23939643. http://www.aafp.org/link_out?pmid=23939643.

- ↑ Rizzoli, P; Mullally, WJ (20 September 2017). "Headache.". The American Journal of Medicine 131 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.09.005. PMID 28939471.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Robbins, Matthew S.; Starling, Amaal J.; Pringsheim, Tamara M.; Becker, Werner J.; Schwedt, Todd J. (2016). "Treatment of Cluster Headache: The American Headache Society Evidence-Based Guidelines". Headache 56 (7): 1093–106. doi:10.1111/head.12866. PMID 27432623.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Fischera, M; Marziniak, M; Gralow, I; Evers, S (2008). "The Incidence and Prevalence of Cluster Headache: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies". Cephalalgia 28 (6): 614–8. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01592.x. PMID 18422717.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Goadsby, Peter J. (2022). "Chapter 430" (in English). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (21st ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 1264268505.

- ↑ Gaul, C; Diener, H; Müller, OM (2011). "Cluster Headache Clinical Features and Therapeutic Options". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 108 (33): 543–549. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2011.0543. PMID 21912573.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 "Management of cluster headache". American Family Physician 71 (4): 717–24. February 2005. PMID 15742909. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2005/0215/p717.html.

- ↑ Capobianco, David; Dodick, David (2006). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Cluster Headache". Seminars in Neurology 26 (2): 242–59. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939925. PMID 16628535.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Friedman, Benjamin Wolkin; Grosberg, Brian Mitchell (2009). "Diagnosis and Management of the Primary Headache Disorders in the Emergency Department Setting". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 27 (1): 71–87, viii. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2008.09.005. PMID 19218020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Migraine and cluster headache - the common link.". The Journal of Headache and Pain 19 (1): 89. 2018. doi:10.1186/s10194-018-0909-4. PMID 30242519.

- ↑ Marmura, Michael J; Pello, Scott J; Young, William B (2010). "Interictal pain in cluster headache". Cephalalgia 30 (12): 1531–4. doi:10.1177/0333102410372423. PMID 20974600.

- ↑ Meyer, Eva Laudon; Laurell, Katarina; Artto, Ville; Bendtsen, Lars; Linde, Mattias; Kallela, Mikko; Tronvik, Erling; Zwart, John-Anker et al. (2009). "Lateralization in cluster headache: A Nordic multicenter study". The Journal of Headache and Pain 10 (4): 259–63. doi:10.1007/s10194-009-0129-z. PMID 19495933.

- ↑ Bahra, A; May, A; Goadsby, PJ (2002). "Cluster headache: A prospective clinical study with diagnostic implications". Neurology 58 (3): 354–61. doi:10.1212/wnl.58.3.354. PMID 11839832.

- ↑ Noshir Mehta; George E. Maloney; Dhirendra S. Bana; Steven J. Scrivani (20 September 2011). Head, Face, and Neck Pain Science, Evaluation, and Management: An Interdisciplinary Approach. John Wiley & Sons. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-118-20995-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=hgzeUKoeaTcC&pg=PT199.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Robbins, Matthew S. (2013). "The Psychiatric Comorbidities of Cluster Headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports 17 (2): 313. doi:10.1007/s11916-012-0313-8. PMID 23296640.

- ↑ The 5-Minute Sports Medicine Consult (2 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. p. 87. ISBN 9781451148121. https://books.google.com/books?id=-LOm9enAxQ8C&pg=PA87.

- ↑ Matharu M, Goadsby P (2001). "Cluster Headache". Practical Neurology 1: 42. doi:10.1046/j.1474-7766.2001.00505.x.

- ↑ Matharu, Manjit S; Goadsby, Peter J (2014). "Cluster headache: Focus on emerging therapies". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 4 (5): 895–907. doi:10.1586/14737175.4.5.895. PMID 15853515.

- ↑ Goadsby P, Mitchell N (1999). "Cluster Headaches". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/rn/talks/8.30/helthrpt/stories/s42434.htm.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 "IHS Classification ICHD-II 3.1 Cluster headache". The International Headache Society. http://www.ihs-classification.org/en/02_klassifikation/02_teil1/03.01.00_cluster.html.

- ↑ Liang, Jen-Feng; Chen, Yung-Tai; Fuh, Jong-Ling; Li, Szu-Yuan; Liu, Chia-Jen; Chen, Tzeng-Ji; Tang, Chao-Hsiun; Wang, Shuu-Jiun (2012). "Cluster headache is associated with an increased risk of depression: A nationwide population-based cohort study". Cephalalgia 33 (3): 182–9. doi:10.1177/0333102412469738. PMID 23212294.

- ↑ Jensen, RM; Lyngberg, A; Jensen, RH (2016). "Burden of Cluster Headache". Cephalalgia 27 (6): 535–41. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01330.x. PMID 17459083.

- ↑ Tabaee D., Payam; Rizzoli, P; Pecis, M (2020). "Right-to-left shunt and obstructive sleep apnea in cluster headache". Neurology & Neurosc. 1 (1): 1–3. https://www.sciencexcel.com/articles/Right-to-left%20shunt%20and%20obstructive%20sleep%20apnea%20in%20cluster%20headache.

- ↑ Pringsheim, Tamara (2014). "Cluster Headache: Evidence for a Disorder of Circadian Rhythm and Hypothalamic Function". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 29 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1017/S0317167100001694. PMID 11858532.

- ↑ Dodick, David W.; Eross, Eric J.; Parish, James M. (2003). "Clinical, Anatomical, and Physiologic Relationship Between Sleep and Headache". Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 43 (3): 282–92. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03055.x. PMID 12603650.

- ↑ "Cluster headaches:Pattern of attacks". Gov.UK. 22 May 2017. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cluster-headaches/.

- ↑ Torelli, Paola; Manzoni, Gian Camillo (2002). "What predicts evolution from episodic to chronic cluster headache?". Current Pain and Headache Reports 6 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1007/s11916-002-0026-5. PMID 11749880.

- ↑ Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) (2013). "The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version)". Cephalalgia 33 (9): 629–808. doi:10.1177/0333102413485658. PMID 23771276. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/89115/1/89115.pdf.

- ↑ "Cluster headache: insights from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging". Neurological Sciences 40 (Suppl 1): 45–47. 2019. doi:10.1007/s10072-019-03874-8. PMID 30941629.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "Family History of Cluster HeadacheA Systematic Review". JAMA Neurology 77 (7): 887–896. 2020. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.0682. PMID 32310255.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Pinessi, L.; Rainero, I.; Rivoiro, C.; Rubino, E.; Gallone, S. (2005). "Genetics of cluster headache: An update". The Journal of Headache and Pain 6 (4): 234–6. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0194-x. PMID 16362673.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 O'Connor, Emer; Simpson, Benjamin S.; Houlden, Henry; Vandrovcova, Jana; Matharu, Manjit (2020-04-25). "Prevalence of familial cluster headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Headache and Pain 21 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/s10194-020-01101-w. ISSN 1129-2377. PMID 32334514.

- ↑ Schürks, Markus; Diener, Hans-Christoph (2008). "Cluster headache and lifestyle habits". Current Pain and Headache Reports 12 (2): 115–21. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0022-5. PMID 18474191.

- ↑ Pringsheim, Tamara (February 2002). "Cluster headache: evidence for a disorder of circadian rhythm and hypothalamic function". Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 29 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1017/S0317167100001694. PMID 11858532.

- ↑ Dasilva, Alexandre F. M.; Goadsby, Peter J.; Borsook, David (2007). "Cluster headache: A review of neuroimaging findings". Current Pain and Headache Reports 11 (2): 131–6. doi:10.1007/s11916-007-0010-1. PMID 17367592.

- ↑ "Headache diary: helping you manage your headache". NPS.org.au. http://www.nps.org.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/160003/NPS_Headache_Diary_0612.pdf.

- ↑ Clarke, C E (2005). "Ability of a nurse specialist to diagnose simple headache disorders compared with consultant neurologists". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 76 (8): 1170–2. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.057968. PMID 16024902.

- ↑ Bahra, A.; Goadsby, P. J. (2004). "Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 109 (3): 175–9. doi:10.1046/j.1600-0404.2003.00237.x. PMID 14763953.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Van Alboom, E; Louis, P; Van Zandijcke, M; Crevits, L; Vakaet, A; Paemeleire, K (2009). "Diagnostic and therapeutic trajectory of cluster headache patients in Flanders". Acta Neurologica Belgica 109 (1): 10–7. PMID 19402567.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Tfelt-Hansen, Peer C.; Jensen, Rigmor H. (2012). "Management of Cluster Headache". CNS Drugs 26 (7): 571–80. doi:10.2165/11632850-000000000-00000. PMID 22650381.

- ↑ Klapper, Jack A.; Klapper, Amy; Voss, Tracy (2000). "The Misdiagnosis of Cluster Headache: A Nonclinic, Population-Based, Internet Survey". Headache 40 (9): 730–5. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2000.00127.x. PMID 11091291.

- ↑ Prakash, Sanjay; Shah, Nilima D; Chavda, Bhavna V (2010). "Cluster headache responsive to indomethacin: Case reports and a critical review of the literature". Cephalalgia 30 (8): 975–82. doi:10.1177/0333102409357642. PMID 20656709.

- ↑ Sjaastad, O; Vincent, M (2010). "Indomethacin responsive headache syndromes: Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania and Hemicrania continua. How they were discovered and what we have learned since". Functional Neurology 25 (1): 49–55. PMID 20626997.

- ↑ Sanjay Prakash; Nilima D Shah; Bhavna V Chavda (2010). "Cluster headache responsive to indomethacin: Case reports and a critical review of the literature". Cephalalgia 30 (8): 975–982. doi:10.1177/0333102409357642. PMID 20656709.

- ↑ Rizzoli, P; Mullally, WJ (September 2017). "Headache". American Journal of Medicine S0002-9343 (17): 30932–4. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.09.005. PMID 28939471.

- ↑ Benoliel, Rafael (2012). "Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias". British Journal of Pain 6 (3): 106–23. doi:10.1177/2049463712456355. PMID 26516482.

- ↑ Nalini Vadivelu; Alan David Kaye; Jack M. Berger (2012-11-28). Essentials of palliative care. New York, NY: Springer. p. 335. ISBN 9781461451648. https://books.google.com/books?id=hGBSe3r_VDUC&pg=PA335.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 May, A.; Leone, M.; Áfra, J.; Linde, M.; Sándor, P. S.; Evers, S.; Goadsby, P. J. (2006). "EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias". European Journal of Neurology 13 (10): 1066–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x. PMID 16987158.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Verapamil and Cluster Headache: Still a Mystery. A Narrative Review of Efficacy, Mechanisms and Perspectives". Headache 59 (8): 1198–1211. 2019. doi:10.1111/head.13603. PMID 31339562.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Butticè, Claudio (2022). What you need to know about headaches. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. ISBN 978-1-4408-7531-1. OCLC 1259297708. https://www.abc-clio.com/products/a6280c/.

- ↑ Magis, Delphine; Schoenen, Jean (2011). "Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in Chronic Cluster Headache". Peripheral Nerve Stimulation. Progress in Neurological Surgery. 24. pp. 126–32. doi:10.1159/000323045. ISBN 978-3-8055-9489-9.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 Martelletti, Paolo; Jensen, Rigmor H; Antal, Andrea; Arcioni, Roberto; Brighina, Filippo; De Tommaso, Marina; Franzini, Angelo; Fontaine, Denys et al. (2013). "Neuromodulation of chronic headaches: Position statement from the European Headache Federation". The Journal of Headache and Pain 14 (1): 86. doi:10.1186/1129-2377-14-86. PMID 24144382.

- ↑ Bartsch, Thorsten; Paemeleire, Koen; Goadsby, Peter J (2009). "Neurostimulation approaches to primary headache disorders". Current Opinion in Neurology 22 (3): 262–8. doi:10.1097/wco.0b013e32832ae61e. PMID 19434793.

- ↑ Evers, Stefan (2010). "Pharmacotherapy of cluster headache". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 11 (13): 2121–7. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.496454. PMID 20569084.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Matharu M (9 February 2010). "Cluster headache". Clinical Evidence 2010. PMID 21718584.

- ↑ Ailani, Jessica; Young, William B. (2009). "The role of nerve blocks and botulinum toxin injections in the management of cluster headaches". Current Pain and Headache Reports 13 (2): 164–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-009-0028-7. PMID 19272284.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Bennett, Michael H; French, Christopher; Schnabel, Alexander; Wasiak, Jason; Kranke, Peter; Weibel, Stephanie (2015). "Normobaric and hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment and prevention of migraine and cluster headache". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. pp. CD005219. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005219.pub3.

- ↑ "Cluster headache". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. 2012-11-02. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000786.htm.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Law, Simon; Derry, Sheena; Moore, R Andrew (2013). "Triptans for acute cluster headache". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018. pp. CD008042. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008042.pub3.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Paemeleire, Koen; Evers, Stefan; Goadsby, Peter J. (2008). "Medication-overuse headache in patients with cluster headache". Current Pain and Headache Reports 12 (2): 122–7. doi:10.1007/s11916-008-0023-4. PMID 18474192.

- ↑ Johnson, Jacinta L; Hutchinson, Mark R; Williams, Desmond B; Rolan, Paul (2012). "Medication-overuse headache and opioid-induced hyperalgesia: A review of mechanisms, a neuroimmune hypothesis and a novel approach to treatment". Cephalalgia 33 (1): 52–64. doi:10.1177/0333102412467512. PMID 23144180.

- ↑ Watkins, Linda R.; Hutchinson, Mark R.; Rice, Kenner C.; Maier, Steven F. (2009). "The "Toll" of Opioid-Induced Glial Activation: Improving the Clinical Efficacy of Opioids by Targeting Glia". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 30 (11): 581–91. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2009.08.002. PMID 19762094.

- ↑ Saper, Joel R.; Da Silva, Arnaldo Neves (2013). "Medication Overuse Headache: History, Features, Prevention and Management Strategies". CNS Drugs 27 (11): 867–77. doi:10.1007/s40263-013-0081-y. PMID 23925669.

- ↑ Matharu, M (2010). "Cluster headache". BMJ Clinical Evidence 2010. PMID 21718584.

- ↑ Malu, Omojo Odihi; Bailey, Jonathan; Hawks, Matthew Kendall (January 2022). "Cluster Headache: Rapid Evidence Review". American Family Physician 105 (1): 24–32. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 35029932. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2022/0100/p24.html#afp20220100p24-b45.

- ↑ Ishaq Abu-Arafeh; Aynur Özge (2016). Headache in Children and Adolescents: A Case-Based Approach. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-319-28628-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=sf3cDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA62.

- ↑ Harris W.: Neuritis and Neuralgia. p. 307-12. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1926.

- ↑ Bickerstaff E (1959). "The periodic migrainous neuralgia of Wilfred Harris". The Lancet 273 (7082): 1069–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(59)90651-8. PMID 13655672.

- ↑ Boes, CJ; Capobianco, DJ; Matharu, MS; Goadsby, PJ (2016). "Wilfred Harris' Early Description of Cluster Headache". Cephalalgia 22 (4): 320–6. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00360.x. PMID 12100097.

- ↑ Pearce, J M S (2007). "Gerardi van Swieten: Descriptions of episodic cluster headache". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 78 (11): 1248–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.123091. PMID 17940171.

- ↑ "A new syndrome of vascular headache: results of treatment with histamine: preliminary report". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 14: 257. 1939.

- ↑ Headache in Clinical Practice (Second ed.). Taylor & Francis. 2002.[page needed]

- ↑ Johnson, Tim (16 May 2013). "Researcher works to unlock mysteries of migraines". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/05/16/researcher-unlocking-mysteries-migraines/2165363/.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Sun-Edelstein, Christina; Mauskop, Alexander (2011). "Alternative Headache Treatments: Nutraceuticals, Behavioral and Physical Treatments". Headache 51 (3): 469–83. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01846.x. PMID 21352222.

- ↑ Vollenweider, Franz X.; Kometer, Michael (2010). "The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: Implications for the treatment of mood disorders". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11 (9): 642–51. doi:10.1038/nrn2884. PMID 20717121.

- ↑ Brandt, Roemer B.; Doesborg, Patty G. G.; Haan, Joost; Ferrari, Michel D.; Fronczek, Rolf (2020-02-01). "Pharmacotherapy for Cluster Headache" (in en). CNS Drugs 34 (2): 171–184. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00696-2. ISSN 1179-1934. PMID 31997136.

- ↑ "Psilocybin for the Treatment of Cluster Headache - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov" (in en). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02981173.

- ↑ A Study Comparing the Efficacy and Safety of TEV-48125 (Fremanezumab) for the Prevention of Chronic Cluster Headache (CCH). 28 January 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02964338.

- ↑ A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of TEV-48125 (Fremanezumab) for the Prevention of Episodic Cluster Headache (ECH). 2 July 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02945046.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|