Chemistry:Psilocybin

Psilocybin, also known as 4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (4-PO-DMT),[lower-alpha 1] is a naturally occurring tryptamine alkaloid and investigational drug found in more than 200 species of mushrooms, with hallucinogenic and serotonergic effects.[2][3] Effects include euphoria, changes in perception, a distorted sense of time (via brain desynchronization),[4] and perceived spiritual experiences. It can also cause adverse reactions such as nausea and panic attacks.

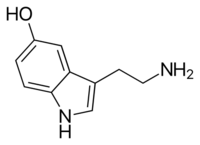

Psilocybin is a prodrug of psilocin.[2] That is, the compound itself is biologically inactive but quickly converted by the body to psilocin.[2] Psilocybin is transformed into psilocin by dephosphorylation mediated via phosphatase enzymes.[5][2] Psilocin is chemically related to the neurotransmitter serotonin and acts as a non-selective agonist of the serotonin receptors.[2] Activation of one serotonin receptor, the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, is specifically responsible for the hallucinogenic effects of psilocin and other serotonergic psychedelics.[2] Psilocybin is usually taken orally.[2] By this route, its onset is about 20 to 50 minutes, peak effects occur after around 60 to 90 minutes, and its duration is about 4 to 6 hours.[6][7][2][8]

Psilocybin mushrooms were used ritualistically in pre-Columbian Mexico, but claims of their widespread ancient use are largely exaggerated and shaped by modern idealization and ideology.[9] In 1958, the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann isolated psilocybin and psilocin from the mushroom Psilocybe mexicana. His employer, Sandoz, marketed and sold pure psilocybin to physicians and clinicians worldwide for use in psychedelic therapy. Increasingly restrictive drug laws of the 1960s and the 1970s curbed scientific research into the effects of psilocybin and other hallucinogens, but its popularity as an entheogen grew in the next decade, owing largely to the increased availability of information on how to cultivate psilocybin mushrooms.

Possession of psilocybin-containing mushrooms has been outlawed in most countries, and psilocybin has been classified as a Schedule I controlled substance under the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Psilocybin is being studied as a possible medicine in the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as depression, substance use disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and other conditions such as cluster headaches.[10] Psilocybin was approved for treatment-resistant depression in Australia in 2023.[11][12] It is in late-stage clinical trials in the United States for treatment-resistant depression.[13][14][15] Especially at higher doses and combined with psychological support, psilocybin can produce rapid and sometimes lasting antidepressant effects that generally outperform placebo but show only modest advantages over conventional SSRIs; evidence quality is generally low and trial bias is common.

Uses

Psilocybin is used recreationally, spiritually (as an entheogen), and medically.[16] It is primarily taken orally, but other routes of administration, such as intravenous injection, are sometimes employed by licensed medical researchers using pharmaceutical-grade psilocybin powder designed for injection. Injection should never be attempted by unlicensed people.[17]

Medical

In 2023, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approved psilocybin for treatment of treatment-resistant depression in Australia.[18][19][20] It is also under development for the treatment of depression and for various other indications elsewhere, such as the United States and Europe, but has not yet been approved in other countries (see below).[21][10][15]

Dosing

Psilocybin is used as a psychedelic at doses of 5 to 40 mg orally.[8][22] Low doses are 5 to 10 mg, an intermediate or "good effect" dose is 20 mg, and high or ego-dissolution doses are 30 to 40 mg.[8][22] Psilocybin's effects can be subjectively perceived at a dose as low as 3 mg per 70 kg body weight.[22][23] Microdosing involves the use of subthreshold psilocybin doses of less than 2.5 mg.[8][22]

When psilocybin is used in the form of psilocybin-containing mushrooms, microdoses are 0.1 g to 0.3 g and psychedelic doses are 1.0 g to 3.5–5.0 g in the case of dried mushrooms.[24][25][17] The preceding 1.0 to 5.0 g range corresponds to psilocybin doses of about 10 to 50 mg.[17] Psilocybin-containing mushrooms vary in their psilocybin and psilocin content, but are typically around 1% of the dried weight of the mushrooms (in terms of total or combined psilocybin and psilocin content).[25][26][27][17][5][28][29][30] Psilocin is about 1.4 times as potent as psilocybin because of the two compounds' difference in molecular weight.[27][31][32]

Available forms

Psilocybin is most commonly consumed in the form of psilocybin-containing mushrooms, such as Psilocybe species like Psilocybe cubensis. It may also be prepared synthetically, but outside of research settings it is not typically used in this form. Regardless of form, psilocybin is usually taken orally. The psilocybin present in certain species of mushrooms can be ingested in several ways: by consuming fresh or dried fruit bodies, by preparing an herbal tea, or by combining with other foods to mask the bitter taste.[33] In rare cases people have intravenously injected mushroom extracts, with serious medical complications such as systemic mycological infection and hospitalization.[34][35][36][37] Another form of psilocybin (as well as of related psychedelics like 4-AcO-DMT) is mushroom edibles such as chocolate bars and gummies, which may be purchased at psychedelic mushroom stores.

Effects

Psilocybin produces a variety of psychological, perceptual, interpersonal, and physical effects.[8]

Psychological and perceptual effects

After ingesting psilocybin, the user may experience a wide range of emotional effects, which can include disorientation, lethargy, giddiness, euphoria, joy, and depression. In one study, 31% of volunteers given a high dose reported feelings of significant fear and 17% experienced transient paranoia.[34] In studies at Johns Hopkins, among those given a moderate dose (but enough to "give a high probability of a profound and beneficial experience"), negative experiences were rare, whereas one-third of those given a high dose experienced anxiety or paranoia.[38][39] Low doses can induce hallucinatory effects. Closed-eye hallucinations may occur, where the affected person sees multicolored geometric shapes and vivid imaginative sequences.[23] Some people report synesthesia, such as tactile sensations when viewing colors.[40]: 175 At higher doses, psilocybin can lead to "intensification of affective responses, enhanced ability for introspection, regression to primitive and childlike thinking, and activation of vivid memory traces with pronounced emotional undertones".[41] Open-eye visual hallucinations are common and may be very detailed, although rarely confused with reality.[23]

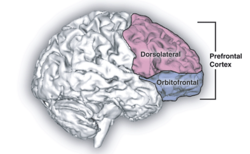

Psilocybin is known to strongly affect the subjective experience of the passage of time.[42][4] Users often feel as if time is slowed down, resulting in the perception that "minutes appear to be hours" or "time is standing still".[43] Studies have demonstrated that psilocybin significantly impairs subjects' ability to gauge time intervals longer than 2.5 seconds, impairs their ability to synchronize to inter-beat intervals longer than 2 seconds, and reduces their preferred tapping rate.[43][44] These results are consistent with the drug's role in affecting prefrontal cortex activity[45] and the role that the prefrontal cortex plays in time perception,[46] but the neurochemical basis of psilocybin's effects on perception of time is not known with certainty.[47]

Users having a pleasant experience can feel a sense of connection to others, nature, and the universe; other perceptions and emotions are also often intensified. Users having an unpleasant experience (a "bad trip") describe a reaction accompanied by fear, other unpleasant feelings, and occasionally by dangerous behavior. The term "bad trip" is generally used to describe a reaction characterized primarily by fear or other unpleasant emotions, not just a transitory experience of such feelings. A variety of factors may contribute to a bad trip, including "tripping" during an emotional or physical low or in a non-supportive environment (see: set and setting). Ingesting psilocybin in combination with other drugs, including alcohol, can also increase the likelihood of a bad trip.[34][48] Other than the duration of the experience, the effects of psilocybin are similar to comparable doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) or mescaline. But in the Psychedelics Encyclopedia, author Peter Stafford writes: "The psilocybin experience seems to be warmer, not as forceful and less isolating. It tends to build connections between people, who are generally much more in communication than when they use LSD."[49]: 273

Set and setting and moderating factors

The effects of psilocybin are highly variable and depend on the mindset and environment in which the user has the experience, factors commonly called set and setting. In the early 1960s, Timothy Leary and his Harvard colleagues investigated the role of set and setting in psilocybin's effects. They administered the drug to 175 volunteers (from various backgrounds) in an environment intended to be similar to a comfortable living room. 98 of the subjects were given questionnaires to assess their experiences and the contribution of background and situational factors. Those who had prior experience with psilocybin reported more pleasant experiences than those for whom the drug was novel. Group size, dose, preparation, and expectancy were important determinants of the drug response. In general, those in groups of more than eight felt that the groups were less supportive and their experiences less pleasant. Conversely, smaller groups (fewer than six) were seen as more supportive and reported more positive reactions to the drug in those groups. Leary and colleagues proposed that psilocybin heightens suggestibility, making a user more receptive to interpersonal interactions and environmental stimuli.[50] These findings were affirmed in a later review by Jos ten Berge (1999), who concluded that dose, set, and setting are fundamental factors in determining the outcome of experiments that tested the effects of psychedelic drugs on artists' creativity.[51]

Further studies demonstrate that supportive settings significantly reduce the likelihood of adverse reactions, including panic, paranoia, or psychological distress. Positive therapeutic outcomes are strongly correlated with the participant's trust in the environment and the facilitators.[52][53]

Theory of mind network and default mode network

Psychedelics, including psilocybin, have been shown to affect different clusters of brain regions known as the "theory of mind network" (ToMN) and the default mode network (DMN).[54] The ToMN involves making inferences and understanding social situations based on patterns,[55] whereas the DMN relates more to introspection and one's sense of self.[54] The DMN, in particular, is related to increased rumination and worsening self-image in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD).[56] In studies done with single use psilocybin, areas of the DMN showed decreased functional connectivity (communication between areas of the brain). This provides functional insight into the work of psilocybin in increasing one's sense of connection to one's surroundings, as the areas of the brain involved in introspection decrease in functionality under the effects of the drug.[57] Conversely, areas of the brain involved in the ToMN showed increased activity and functional activation in response to psychedelics. These results were not unique to psilocybin and there was no significant difference in brain activation found in similar trials of mescaline and LSD. Information and studies into the DMN and ToMN are relatively sparse and their connections to other psychiatric illnesses and the use of psychedelics is still largely unknown.[54]

Group perceptions

Through further anthropological studies regarding "personal insights"[58] and the psychosocial effects of psilocybin, it can be seen in many traditional societies that powerful mind-active substances such as psilocybin are regularly "consumed ritually for therapeutic purposes or for transcending normal, everyday reality".[59] Positive effects that psilocybin has on individuals can be observed by taking on an anthropological approach and moving away from the Western biomedical view; this is aided by the studies done by Leary.[60] Within certain traditional societies, where the use of psilocybin is frequent for shamanic healing rituals, group collectives praise their guide, healer and shaman for helping alleviate their pains, aches and hurt. They do this through a group ritual practice where the group, or just the guide, ingests psilocybin to help extract any "toxic psychic residues or sorcerous implants"[59] found in one's body.

Group therapies using "classic" psychedelics are becoming more commonly used in the Western world in clinical practice.[61] This is speculated to grow, provided the evidence remains indicative of their safety and efficacy.[62] In social sense, the group is shaped by their experiences surrounding psilocybin and how they view the fungus collectively. As mentioned in the anthropology article,[59] the group partakes in a "journey" together, thus adding to the spiritual, social body where roles, hierarchies and gender are subjectively understood.[59]

Cultural significance and "mystical" experiences

Psilocybin mushrooms have been and continue to be used in Indigenous American cultures in religious, divinatory, or spiritual contexts. Reflecting the meaning of the word entheogen ("the god within"), the mushrooms are revered as powerful spiritual sacraments that provide access to sacred worlds. Typically used in small group community settings, they enhance group cohesion and reaffirm traditional values.[63] Terence McKenna documented the worldwide practices of psilocybin mushroom usage as part of a cultural ethos relating to the Earth and mysteries of nature, and suggested that mushrooms enhanced self-awareness and a sense of contact with a "Transcendent Other"—reflecting a deeper understanding of our connectedness with nature.[64]

Psychedelic drugs can induce states of consciousness that have lasting personal meaning and spiritual significance in religious or spiritually inclined people; these states are called mystical experiences. Some scholars have proposed that many of the qualities of a drug-induced mystical experience are indistinguishable from mystical experiences achieved through non-drug techniques such as meditation or holotropic breathwork.[65][66] In the 1960s, Walter Pahnke and colleagues systematically evaluated mystical experiences (which they called "mystical consciousness") by categorizing their common features. According to Pahnke, these categories "describe the core of a universal psychological experience, free from culturally determined philosophical or theological interpretations", and allow researchers to assess mystical experiences on a qualitative, numerical scale.[67]

In the 1962 Marsh Chapel Experiment, run by Pahnke at the Harvard Divinity School under Leary's supervision,[68] almost all the graduate degree divinity student volunteers who received psilocybin reported profound religious experiences.[69] One of the participants was religious scholar Huston Smith, author of several textbooks on comparative religion; he called his experience "the most powerful cosmic homecoming I have ever experienced."[70] In a 25-year followup to the experiment, all the subjects given psilocybin said their experience had elements of "a genuine mystical nature and characterized it as one of the high points of their spiritual life".[71]: 13 Psychedelic researcher Rick Doblin considered the study partially flawed due to incorrect implementation of the double-blind procedure and several imprecise questions in the mystical experience questionnaire. Nevertheless, he said that the study cast "considerable doubt on the assertion that mystical experiences catalyzed by drugs are in any way inferior to non-drug mystical experiences in both their immediate content and long-term effects".[71]: 24 Psychiatrist William A. Richards echoed this sentiment, writing in a 2007 review, "[psychedelic] mushroom use may constitute one technology for evoking revelatory experiences that are similar, if not identical, to those that occur through so-called spontaneous alterations of brain chemistry."[72]

A group of researchers from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine led by Roland Griffiths conducted a study to assess the immediate and long-term psychological effects of the psilocybin experience, using a modified version of the mystical experience questionnaire and a rigorous double-blind procedure.[73] When asked in an interview about the similarity of his work to Leary's, Griffiths explained the difference: "We are conducting rigorous, systematic research with psilocybin under carefully monitored conditions, a route which Dr. Leary abandoned in the early 1960s."[74] Experts have praised the National Institute of Drug Abuse-funded study, published in 2006, for the soundness of its experimental design.[lower-alpha 2] In the experiment, 36 volunteers with no experience with hallucinogens were given psilocybin and methylphenidate (Ritalin) in separate sessions; the methylphenidate sessions served as a control and psychoactive placebo. The degree of mystical experience was measured using a questionnaire developed by Ralph W. Hood;[75] 61% of subjects reported a "complete mystical experience" after their psilocybin session, while only 13% reported such an outcome after their experience with methylphenidate. Two months after taking psilocybin, 79% of the participants reported moderately to greatly increased life satisfaction and sense of well-being. About 36% of participants also had a strong to extreme "experience of fear" or dysphoria (i.e., a "bad trip") at some point during the psilocybin session (which was not reported by any subject during the methylphenidate session); about one-third of these (13% of the total) reported that this dysphoria dominated the entire session. These negative effects were reported to be easily managed by the researchers and did not have a lasting negative effect on the subject's sense of well-being.[76]

A follow-up study 14 months later confirmed that participants continued to attribute deep personal meaning to the experience. Almost a third of the subjects reported that the experience was the single most meaningful or spiritually significant event of their lives, and over two-thirds reported it was among their five most spiritually significant events. About two-thirds said the experience increased their sense of well-being or life satisfaction.[69] Even after 14 months, those who reported mystical experiences scored on average 4 percentage points higher on the personality trait of Openness/Intellect; personality traits are normally stable across the lifespan for adults. Likewise, in a 2010 web-based questionnaire study designed to investigate user perceptions of the benefits and harms of hallucinogenic drug use, 60% of the 503 psilocybin users reported that their use of psilocybin had a long-term positive impact on their sense of well-being.[34][77]

Physical effects

Common responses include pupil dilation (93%); changes in heart rate (100%), including increases (56%), decreases (13%), and variable responses (31%); changes in blood pressure (84%), including hypotension (34%), hypertension (28%), and general instability (22%); changes in stretch reflex (86%), including increases (80%) and decreases (6%); nausea (44%); tremor (25%); and dysmetria (16%) (inability to properly direct or limit motions).[78][lower-alpha 3] Psilocybin's sympathomimetic or cardiovascular effects, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, are usually mild.[16][78] On average, peak heart rate is increased by 5 bpm, peak systolic blood pressure by 10 to 15 mm Hg, and peak diastolic blood pressure by 5 to 10 mm Hg.[16][78] But temporary increases in blood pressure can be a risk factor for users with preexisting hypertension.[23] Psilocybin's somatic effects have been corroborated by several early clinical studies.[80] A 2005 magazine survey of clubgoers in the UK found that over a quarter of those who had used psilocybin mushrooms in the preceding year experienced nausea or vomiting, although this was caused by the mushroom rather than psilocybin itself.[34] In one study, administration of gradually increasing doses of psilocybin daily for 21 days had no measurable effect on electrolyte levels, blood sugar levels, or liver toxicity tests.[78]

Onset and duration

The onset of action of psilocybin taken orally is 0.5 to 0.8 hours (30–50 minutes) on average, with a range of 0.1 to 1.5 hours (5–90 minutes).[8][6] Peak psychoactive effects occur at about 1.0 to 2.2 hours (60–130 minutes).[6][8] The time to offset of psilocybin orally is about 6 to 7 hours on average.[81] The duration of action of psilocybin is about 4 to 6 hours (range 3–12 hours) orally.[6][8][7] A small dose of 1 mg by intravenous injection had a duration of 15 to 30 minutes.[78][82] In another study, 2 mg psilocybin by intravenous injection given over 60 seconds had an immediate onset, reached a sustained peak after 4 minutes, and subsided completely after 45 to 60 minutes.[83][84]

Contraindications

Contraindications of psilocybin are mostly psychiatric conditions that increase the risk of psychological distress, including the rare adverse effect of psychosis during or after the psychedelic experience.[6][85] These conditions may include history of psychosis, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or borderline personality disorder.[6][86] Further research may provide more safety information about the use of psilocybin in people with such conditions.[6] It is notable in this regard that psilocybin and other psychedelics are being studied for the potential treatment of all the preceding conditions.[87][88][89][90][91][92]

Psilocybin is also considered to be contraindicated in women who are pregnant or breastfeeding due to insufficient research in this population.[6] There are transient increases in heart rate and blood pressure with psilocybin, and hence uncontrolled cardiovascular conditions are a relative contraindication for psilocybin.[6] Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists such as atypical antipsychotics and certain antidepressants may block psilocybin's hallucinogenic effects and hence may be considered contraindicated in this sense.[93][94] Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) may potentiate psilocybin's effects and augment its risks.[93]

Adverse effects

Most of the comparatively few fatal incidents associated with psychedelic mushroom usage involve the simultaneous use of other drugs, especially alcohol. A common adverse effect resulting from psilocybin mushroom use involves "bad trips" or panic reactions, in which people become anxious, confused, agitated, or disoriented.[95] Accidents, self-injury, or suicide attempts can result from serious cases of acute psychotic episodes.[34] No studies have linked psilocybin with birth defects,[96] but it is recommended that pregnant women avoid its usage.[97]

Psychiatric adverse effects

Panic reactions can occur after consumption of psilocybin-containing mushrooms, especially if the ingestion is accidental or otherwise unexpected. Reactions characterized by violent behavior, suicidal thoughts,[98] schizophrenia-like psychosis,[99][100] and convulsions[101] have been reported in the literature. A 2005 survey conducted in the United Kingdom found that almost a quarter of those who had used psilocybin mushrooms in the past year had experienced a panic attack.[34] Less frequently reported adverse effects include paranoia, confusion, prolonged derealization (disconnection from reality), and mania.[77] Psilocybin usage can temporarily induce a state of depersonalization disorder.[102] Usage by those with schizophrenia can induce acute psychotic states requiring hospitalization.[103]

The similarity of psilocybin-induced symptoms to those of schizophrenia has made the drug a useful research tool in behavioral and neuroimaging studies of schizophrenia.[104][105][106] In both cases, psychotic symptoms are thought to arise from a "deficient gating of sensory and cognitive information" in the brain that leads to "cognitive fragmentation and psychosis".[105] Flashbacks (spontaneous recurrences of a previous psilocybin experience) can occur long after psilocybin use. Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD) is characterized by a continual presence of visual disturbances similar to those generated by psychedelic substances. Neither flashbacks nor HPPD are commonly associated with psilocybin usage,[34] and correlations between HPPD and psychedelics are further obscured by polydrug use and other variables.[107]

Tolerance and dependence

Tolerance to psilocybin builds and dissipates quickly; ingesting it more than about once a week can lead to diminished effects. Tolerance dissipates after a few days, so doses can be spaced several days apart to avoid the effect.[109] A cross-tolerance can develop between psilocybin and LSD,[110] and between psilocybin and phenethylamines such as mescaline and DOM.[111]

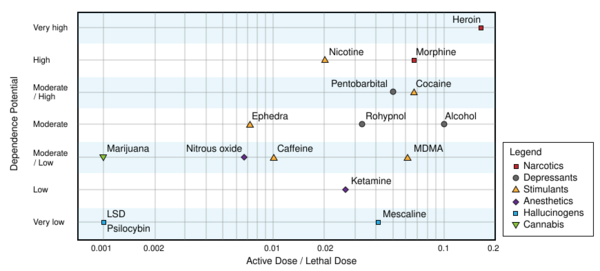

Repeated use of psilocybin does not lead to physical dependence.[78] A 2008 study concluded that, based on U.S. data from 2000 to 2002, adolescent-onset (defined here as ages 11–17) usage of hallucinogenic drugs (including psilocybin) did not increase the risk of drug dependence in adulthood; this was in contrast to adolescent usage of cannabis, cocaine, inhalants, anxiolytic medicines, and stimulants, all of which were associated with "an excess risk of developing clinical features associated with drug dependence".[112] Likewise, a 2010 Dutch study ranked the relative harm of psilocybin mushrooms compared to a selection of 19 recreational drugs, including alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, heroin, and tobacco. Psilocybin mushrooms were ranked as the illicit drug with the lowest harm,[113] corroborating conclusions reached earlier by expert groups in the United Kingdom.[114]

Long-term effects

A potential risk of frequent repeated use of psilocybin and other psychedelics is cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy caused by serotonin 5-HT2B receptor activation.[115][116] But single high doses or widely spaced doses (e.g., months apart) are thought to be safe, and concerns about cardiac toxicity apply more to chronic psychedelic microdosing or very frequent intermittent use (e.g., weekly).[115][116]

Overdose

Psilocybin has low toxicity, meaning that it has a low risk of inducing life-threatening events like breathing or heart problems.[117][95] Research shows that health risks may develop with use of psilocybin. Nonetheless, hospitalizations from it are rare, and overdoses are generally mild and self-limiting.[117][95] The lethal dose of psilocybin in humans is unknown, but has been estimated to be approximately 200 times a typical recreational dose.[117]

A review of the management of psychedelic overdoses suggested that psilocybin-related overdose management should prioritize managing the immediate adverse effects, such as anxiety and paranoia, rather than specific pharmacological interventions, as psilocybin's physiological toxicity tends to be rather limited.[118] One analysis of people hospitalized for psilocybin poisoning found high urine concentrations of phenethylamine (PEA), suggesting that PEA might contribute to the effects of psilocybin poisoning.[118]

Despite acting as non-selective serotonin receptor agonists, psilocybin and other major serotonergic psychedelics like lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) do not cause serotonin syndrome even in the context of extreme overdose.[119][117][120] This is thought to be because they act as partial agonists of serotonin receptors like the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, in contrast to serotonin itself, which is a full agonist.[119][120]

In rats, the median lethal dose (LD50) of psilocybin when administered orally is 280 mg/kg, approximately 1.5 times that of caffeine. The lethal dose of psilocybin when administered intravenously in mice is 285 mg/kg, in rats is 280 mg/kg, and in rabbits is 12.5 mg/kg.[121][122] Psilocybin comprises approximately 1% of the weight of Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms, and so nearly 1.7 kilograms (3.7 lb) of dried mushrooms, or 17 kilograms (37 lb) of fresh mushrooms, would be required for a 60-kilogram (130 lb) person to reach the 280 mg/kg LD50 value of rats.[34] Based on the results of animal studies and limited human case reports, the human lethal dose of psilocybin has been extrapolated to be 2,000 to 6,000 mg, which is around 1,000 times greater than its effective dose of 6 mg and 200 times the typical recreational dose of 10 to 30 mg.[123][117] The Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances assigns psilocybin a relatively high therapeutic index of 641 (higher values correspond to a better safety profile); for comparison, the therapeutic indices of aspirin and nicotine are 199 and 21, respectively.[124] The lethal dose from psilocybin toxicity alone is unknown, and has rarely been documented—as of 2011[update], only two cases attributed to overdosing on hallucinogenic mushrooms (without concurrent use of other drugs) have been reported in the scientific literature, and those may involve factors other than psilocybin.[34][lower-alpha 4]

Interactions

Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists can block the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics like psilocybin.[93][127] Numerous drugs act as serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, including antidepressants like trazodone and mirtazapine, antipsychotics like quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, and other agents like ketanserin, pimavanserin, cyproheptadine, and pizotifen.[93][94] Such drugs are sometimes called "trip killers" because they can prevent or abort psychedelics' hallucinogenic effects.[128][94][129] Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists that have been specifically shown in clinical studies to diminish or abolish psilocybin's effects include ketanserin, risperidone, and chlorpromazine.[93][127]

The serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist buspirone has been found to markedly reduce psilocybin's hallucinogenic effects in humans.[93][127][130][131] Conversely, the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor antagonist pindolol has been found to potentiate the hallucinogenic effects of the related psychedelic dimethyltryptamine (DMT) by 2- to 3-fold in humans.[131][132] Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may modify psilocybin's effects.[93][127][133] One clinical trial found that psilocybin's hallucinogenic and "good drug" effects were not modified by the SSRI escitalopram, but that its "bad drug effects" such as anxiety, as well as ego dissolution, were reduced, among other changes.[127][93][133]

Benzodiazepines such as diazepam, alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam, as well as alcohol, which act as GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, have been limitedly studied in combination with psilocybin and other psychedelics and are not known to directly interact with them.[127][93] But these GABAergic drugs produce effects such as anxiolysis, sedation, and amnesia, and may therefore diminish or otherwise oppose psychedelics' effects.[93][128][94][129][134] Because of this, recreational users often use benzodiazepines and alcohol as "trip killers" to manage difficult hallucinogenic experiences with psychedelics, such as experiences with prominent anxiety.[128][94][129] This strategy's safety is not entirely clear and might have risks,[128][127][94][129] but benzodiazepines have been used to manage psychedelics' adverse psychological effects in clinical studies and in Emergency Rooms.[127][135][136][137][138] A clinical trial of psilocybin and midazolam coadministration found that midazolam clouded psilocybin's effects and impaired memory of the experience.[139][140] Benzodiazepines might interfere with the therapeutic effects of psychedelics like psilocybin, such as sustained antidepressant effects.[141][142]

Psilocin, the active form of psilocybin, is a substrate of the monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzyme MAO-A.[143][81][27] The exact extent to which psilocin (and by extension psilocybin) is metabolized by MAO-A is not fully clear, but has ranged from 4% to 33% in different studies based on metabolite excretion.[143][81][27] Circulating levels of psilocin's deaminated metabolite are far higher than those of free unmetabolized psilocin with psilocybin administration.[21][82] Combination of MAO-substrate psychedelics with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can result in overdose and toxicity.[93] Examples of MAOIs that may potentiate psychedelics behaving as MAO-A substrates, such as psilocin, include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, and moclobemide, as well as harmala alkaloids like harmine and harmaline and chronic tobacco smoking.[93][144] An early clinical study of psilocybin in combination with short-term tranylcypromine pretreatment found that tranylcypromine marginally potentiated psilocybin's peripheral effects, including pressor effects and mydriasis, but overall did not significantly modify its psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects, although some of its emotional effects were said to be reduced and some of its perceptual effects were said to be amplified.[16][145][146]

Psilocin may be metabolized to a minor extent by the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes CYP2D6 and/or CYP3A4 and appears unlikely to be metabolized by other CYP450 enzymes.[143][16] The role of CYP450 enzymes in psilocin's metabolism seems to be small, and so considerable drug interactions with CYP450 inhibitors and/or inducers may not be expected.[143][16] Psilocin's major metabolic pathway is glucuronidation by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes including UGT1A10 and UGT1A9.[127] Diclofenac and probenecid are inhibitors of these enzymes that theoretically might inhibit the metabolism of and thereby potentiate psilocybin's effects,[127] but no clinical research or evidence on this possible interaction exists.[127] Few other drugs are known to influence UGT1A10 or UGT1A9 function.[127]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Psilocybin is a serotonergic psychedelic that acts as a prodrug of psilocin, the active form of the drug.[8][21] Psilocin is a close analogue of the monoamine neurotransmitter serotonin and, like serotonin, acts as a non-selective agonist of the serotonin receptors, including behaving as a partial agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[8][21][27] It shows high affinity for most of the serotonin receptors, with the notable exception of the serotonin 5-HT3 receptor.[8][21][27] Psilocin's affinity for the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is 15-fold higher in humans than in rats due to species differences.[27][147] In addition to interacting with the serotonin receptors, psilocin is a partial serotonin releasing agent with lower potency.[148][149] Unlike certain other psychedelics such as LSD, it appears to show little affinity for many other targets, such as dopamine receptors.[2][8][16][150][151][152] Psilocin is an agonist of the mouse and rat but not human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1).[153][150][154]

Psilocybin's and psilocin's psychedelic effects are mediated specifically by agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[8][21] Selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists like volinanserin block the head-twitch response (HTR), a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects, induced by psilocybin in rodents, and the HTR is similarly absent in serotonin 5-HT2A receptor knockout mice.[21][27][155][154] There is a significant relationship between psilocybin's hallucinogenic effects and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor occupancy in humans.[8][111][156] Psilocybin's psychedelic effects can be blocked by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists like ketanserin and risperidone in humans.[157][8][21][111][99] Activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in layer V of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and consequent glutamate release in this area has been especially implicated in the hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin and other serotonergic psychedelics.[158][159][160][161][162] In addition, region-dependent alterations in brain glutamate levels may be related to the experience of ego dissolution.[163] The cryo-EM structures of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor with psilocin, as well as with various other psychedelics and serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, have been solved and published by Bryan L. Roth and colleagues.[164][165]

Although serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonism mediates the hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin and psilocin, activation of other serotonin receptors also appears to contribute to these compounds' psychoactive and behavioral effects.[111][21][27][166][167][168] Serotonin 5-HT1A receptor activation seems to inhibit the hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin and other psychedelics.[93][130][131][132] Some of psilocybin's non-hallucinogenic behavioral effects in animals can be reversed by antagonists of the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors.[21][27] Psilocybin produces profoundly decreased locomotor and investigatory behavior in rodents, and this appears to be dependent on serotonin 5-HT1A receptor activation but not on activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C receptors.[160][161][169] In addition, the serotonin 5-HT1B receptor has been found to be required for psilocybin's persisting antidepressant- and anxiolytic-like effects as well as acute hypolocomotion in animals.[170] In humans, ketanserin blocked psilocybin's hallucinogenic effects but not all of its cognitive and behavioral effects.[111] Serotonin 5-HT2C receptor activation and downstream inhibition of the mesolimbic dopamine pathway may be involved in the limited addictive potential of serotonergic psychedelics like psilocybin.[171]

In addition to its psychedelic effects, psilocin has been found to produce psychoplastogenic effects in animals, including dendritogenesis, spinogenesis, and synaptogenesis.[172][21][173] It has been found to promote neuroplasticity in the brain in a rapid, robust, and sustained manner with a single dose.[172][21] These effects appear to be mediated by intracellular serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation.[172][21][174][173] The psychoplastogenic effects of psilocybin and other serotonergic psychedelics may be involved in their potential therapeutic benefits in the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as depression.[175][176][177] They may also be involved in the effects of microdosing.[178] Psilocin was also reported to act as a highly potent positive allosteric modulator of the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), one of the receptors of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),[172][16][179] but subsequent studies failed to reproduce these findings and instead found no interaction of psilocin with TrkB.[180] Relatedly, psilocybin has been found not to enhance but rather to inhibit hippocampal neurogenesis in rodents.[172]

Psilocybin produces profound anti-inflammatory effects mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation in preclinical studies.[181][182][183] These effects have a potency similar to that of (R)-DOI, and its anti-inflammatory effects occur at far lower doses than those that produce hallucinogen-like effects in animals.[184][181][182][185] Psilocybin's anti-inflammatory effects might be involved in its potential antidepressant benefits and might also have other therapeutic applications, such as treatment of asthma and neuroinflammation.[181][182][186] They may also be involved in microdosing effects.[187][183] But psychedelics have been found to have anti-inflammatory effects only in the setting of preexisting inflammation and may be pro-inflammatory outside that context.[188] Psilocybin has been found to have a large, long-lasting impact on the intestinal microbiome and to influence the gut–brain axis in animals.[189][190][191][167][192][193] These effects are partially but not fully dependent on its activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A and/or 5-HT2C receptors.[167] Some of psilocybin's behavioral and potential therapeutic effects may be mediated by changes to the gut microbiome.[167][191][193] Transplantation of intestinal contents of psilocybin-treated rodents to untreated rodents resulted in behavioral changes consistent with those of psilocybin administration.[167]

Psilocybin and other psychedelics produce sympathomimetic effects, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure, by activating the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[194][195][196] Long-term repeated use of psilocybin may result in risk of cardiac valvulopathy and other complications by activating serotonin 5-HT2B receptors.[2][115][116][194][195]

There is little or no acute tolerance with psilocybin, and hence its duration is dictated by pharmacokinetics rather than by pharmacodynamics.[8][81] Conversely, tolerance and tachyphylaxis rapidly develop to psilocybin's psychedelic effects with repeated administration in humans.[2][197][160][111] In addition, there is cross-tolerance with the hallucinogenic effects of other psychedelics such as LSD.[2][197][160][111] Psilocybin produces downregulation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the brain in animals, an effect thought to be responsible for the development of tolerance to its psychedelic effects.[2][197][160][111] Serotonin 5-HT2A receptors appear to slowly return over the course of days to weeks after psilocybin administration.[2]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

There has been little research on psilocybin's bioavailability.[198] Its oral bioavailability, as its active form psilocin, was about 55.0% (± ~20%) relative to intravenous administration in one small older study (n=3).[198][21][6][82] After oral administration, psilocybin is detectable in the blood circulation within 20 to 40 minutes, and psilocin is detectable after 30 minutes.[6][27] The mean time to peak levels for psilocin is 1.05 to 3.71 hours in different studies, with most around 2 hours and the upper limit of 3.71 hours being an outlier.[198][199][27]

Psilocybin, in terms of psilocin, shows clear linear or dose-dependent pharmacokinetics.[198][8][21][6][81][200] Maximal concentrations of psilocin were 11 ng/mL, 17 ng/mL, and 21 ng/mL with oral psilocybin doses of 15, 25, and 30 mg psilocybin, respectively.[81] The maximal levels of psilocin have been found to range from 8.2 ng/mL to 37.6 ng/mL across a dose range of 14 to 42 mg.[199] The dose-normalized peak concentration of psilocin is about 0.8 ng/mL/mg.[198] The interindividual variability in the pharmacokinetics of psilocybin is relatively small.[81] There is a very strong positive correlation between dose and psilocin peak levels (R2 = 0.95).[199] The effects of food on the pharmacokinetics of psilocybin have not been reported and are unknown, but no clear sign of food effects has been observed in preliminary analyses.[198] It has also been said that food might delay absorption, reduce peak levels, and reduce bioavailability.[16]

Distribution

Psilocin, the active form of psilocybin, is extensively distributed to all tissues through the bloodstream.[6] Its volume of distribution is 505 to 1,267 L.[198] Psilocybin itself is hydrophilic due to its phosphate group and cannot easily cross the blood–brain barrier.[16][6] Conversely, psilocin is lipophilic and readily crosses the blood–brain barrier to exert effects in the central nervous system.[6] The plasma protein binding of psilocybin is 66% and hence it is moderately plasma protein-bound.[201]

Psilocin (4-HO-DMT) is a close positional isomer of bufotenin (5-HO-DMT), which shows peripheral selectivity, and might be expected to have similarly restricted lipophilicity and blood–brain barrier permeability.[202][203] But psilocin appears to form a tricyclic pseudo-ring system wherein its hydroxyl group and amine interact through hydrogen bonding.[202][203][204][205] This in turn makes psilocin much less polar, more lipophilic, and more able to cross the blood–brain barrier and exert central actions than it would be otherwise.[202][203][204][205] It may also protect psilocin from metabolism by monoamine oxidase (MAO).[202] In contrast, bufotenin is not able to achieve this pseudo-ring system.[202][203][204][205] Accordingly, bufotenin is less lipophilic than psilocin in terms of partition coefficient.[202][203] But bufotenin does still show significant central permeability and, like psilocybin, can produce robust hallucinogenic effects in humans.[203][204][206][207]

Metabolism

Psilocybin is dephosphorylated into its active form psilocin in the body and hence is a prodrug.[6][21][17] Psilocybin is metabolized in the intestines, liver, kidneys, blood, and other tissues and bodily fluids.[198][208][143] There is significant first-pass metabolism of psilocybin and psilocin with oral administration.[198][143] No psilocybin has been detected in the blood in humans after oral administration, suggesting virtually complete dephosphorylation into psilocin with the first pass.[198][21][17][143] It is also said to be converted 90% to 97% into psilocin.[209] The competitive phosphatase inhibitor β-glycerolphosphate, which inhibits psilocybin dephosphorylation, greatly attenuates the behavioral effects of psilocybin in rodents.[27][143][210] Psilocybin undergoes dephosphorylation into psilocin via the acidic environment of the stomach or the actions of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and non-specific esterases in tissues and fluids.[26][208][27]

Psilocin is demethylated and oxidatively deaminated by monoamine oxidase (MAO), specifically monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), into 4-hydroxyindole-3-acetaldehyde (4-HIAL or 4-HIA).[21][17][211] 4-HIAL is then further oxidated into 4-hydroxyindole-3-acetic acid (4-HIAA) by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) or into 4-hydroxytryptophol (4-HTOL or 4-HTP) by alcohol dehydrogenase (ALD).[21][17] Deamination of psilocin by MAO-A appears to be responsible for about 4% or 33% of its metabolism in different studies.[143][81][27] In contrast to psilocin, its metabolites 4-HIAA and 4-HTP showed no affinity for or activation of multiple serotonin receptors and are considered inactive.[21][16][143] Based on in vitro studies, it has been estimated that MAO-A is responsible for about 81% of psilocin's phase I hepatic metabolism.[211] Psilocin and its metabolites are also glucuronidated by UDP-glucuronyltransferases (UGTs).[198][21][17][143] UGT1A10 and UGT1A9 appear to be the most involved.[198][21][27] Psilocybin's glucuronidated metabolites include psilocin-O-glucuronide and 4-HIAA-O-glucuronide.[21][17][143] Approximately 80% of psilocin in blood plasma is in conjugated form, and conjugated psilocin levels are about fourfold higher than levels of free psilocin.[143][27] Plasma 4-HIAA levels are also much higher than those of free psilocin.[21]

Norpsilocin (4-HO-NMT), formed from psilocin via demethylation mediated by the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP2D6, is known to occur in mice in vivo and with human recombinant CYP2D6 in vitro but was not detected in humans in vivo.[143] An oxidized psilocin metabolite of unknown chemical structure is also formed by hydroxyindole oxidase activity of CYP2D6.[143][27] Oxidized psilocin is possibly a quinone-type structure like psilocin iminoquinone (4-hydroxy-5-oxo-N,N-DMT) or psilocin hydroquinone (4,5-dihydroxy-N,N-DMT).[143][27] Additional metabolites formed by CYP2D6 may also be present.[143] Besides CYP2D6, CYP3A4 showed minor activity in metabolizing psilocin, though the produced metabolite is unknown.[143] Other cytochrome P450 enzymes besides CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 appear unlikely to be involved in psilocin metabolism.[143] CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotypes do not modify psilocin exposure in humans, suggesting that CYP2D6 is not critically involved in psilocin metabolism and is unlikely to result in interindividual differences in psilocin kinetics or effects.[16][143] Psilocybin and psilocin might inhibit CYP3A4 and CYP2A6 to some extent, respectively.[199]

Elimination

Psilocybin is eliminated 80% to 85% in urine and 15 to 20% in bile.[16] It is excreted mainly in urine as psilocin-O-glucuronide.[16][208] The drug was eliminated approximately 20% and 80% as psilocin O-glucuronide in different studies.[198][208][27][81] The amount excreted as unchanged psilocin in urine is 1.5 to 3.4%.[198][208][21][81] Studies conflict on the deaminated metabolites of psilocin, with one study finding that only 4% of psilocin is metabolized into 4-HIAA, 4-HIAL, and 4-HTOL[27] and another that psilocybin is excreted 33% in urine as 4-HIAA.[143][81] Findings also conflict on whether psilocybin can be detected in urine, with either no psilocybin excreted or 3% to 10% excreted as unchanged psilocybin.[209][78][198][17][27] A majority of psilocybin and its metabolites is excreted within three hours with oral administration and elimination is almost complete within 24 hours.[27][17][81]

The elimination half-life of psilocybin, as psilocin, is 2.1 to 4.7 hours on average (range 1.2–18.6 hours) orally and 1.2 hours (range 1.8–4.5 hours) intravenously.[198][199][21][27] Psilocin's elimination half-life in mice is 0.9 hours, much faster than in humans.[143] Psilocin O-glucuronide's half-life is about 4 hours in humans and approximately 1 hour in mice.[143]

No dose adjustment of psilocin is thought to be required as psilocin is inactivated mainly via metabolism as opposed to renal elimination.[198][16][81] Accordingly, glomerular filtration rate (GFR) did not affect the pharmacokinetics of psilocybin.[198][16][81]

Miscellaneous

The pharmacokinetics of administered psilocybin and psilocin in rodents, for instance in terms of psilocin tissue distribution kinetics, are described as very similar or identical, suggesting very rapid or near-immediate cleavage of psilocybin into psilocin.[212]

Psilocybin's psychoactive effects and duration are strongly correlated with psilocin levels.[8][81][21]

Single doses of psilocybin of 3 to 30 mg have been found to dose-dependently occupy the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in humans as assessed by imaging studies.[21] The EC50 for occupancy of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor by psilocin in terms of circulating levels has been found to be 1.97 ng/mL.[21]

Body weight and body mass index do not appear to affect psilocybin's pharmacokinetics.[8][16][81] This suggests that body weight-adjusted dosing of psilocybin is unnecessary and may actually be counterproductive, and that fixed-dosing should be preferred.[16][81] Similarly, age does not affect psilocybin's pharmacokinetics.[198] The influence of sex on psilocybin's pharmacokinetics has not been tested.[198]

Chemistry

Physical properties

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring substituted tryptamine that features an indole ring linked to an aminoethyl substituent. It is structurally related to serotonin, a monoamine neurotransmitter that is a derivative of the amino acid tryptophan. Psilocybin is a member of the general class of tryptophan-based compounds that originally functioned as antioxidants in earlier life forms before assuming more complex functions in multicellular organisms, including humans.[213] Other related indole-containing psychedelic compounds include dimethyltryptamine, found in many plant species and in trace amounts in some mammals, and bufotenin, found in the skin of certain amphibians, especially the Colorado River toad.[214]: 10–13

Psilocybin is a white, crystalline solid that is soluble in water, methanol and ethanol but insoluble in nonpolar organic solvents such as chloroform and petroleum ether.[214]: 15 It has a melting point between 220 and 228 °C (428 and 442 °F),[122] and an ammonia-like taste.[215] Its pKa values are estimated to be 1.3 and 6.5 for the two successive phosphate hydroxy groups and 10.4 for the dimethylamine nitrogen, so it typically exists as a zwitterionic structure.[215] There are two known crystalline polymorphs of psilocybin, as well as reported hydrated phases.[216] Psilocybin rapidly oxidizes upon exposure to light—an important consideration when using it as an analytical standard.[217]

Structural analogues

Structural analogues of psilocybin (4-PO-DMT; O-phosphorylpsilocin) and psilocin (4-HO-DMT) include dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), bufotenin (5-HO-DMT), 6-hydroxy-DMT, 4-AcO-DMT (psilacetin; O-acetylpsilocin), 4-PrO-DMT (O-propionylpsilocin), psilomethoxin (4-HO-5-MeO-DMT; 5-methoxypsilocin), ethocybin (4-PO-DET), baeocystin (4-PO-NMT), aeruginascin (4-PO-TMT), and norbaeocystin (4-PO-T), among others.

Laboratory synthesis

Albert Hofmann et al. were the first to synthesize psilocybin, in 1958. Since then, various chemists have improved the methods for laboratory synthesis and purification of psilocybin. In particular, Shirota et al. reported a novel method in 2003 for the synthesis of psilocybin at the gram scale from 4-hydroxyindole that does not require chromatographic purification. Fricke et al. described an enzymatic pathway for the synthesis of psilocybin and psilocin, publishing their results in 2017. Sherwood et al. significantly improved upon Shirota's method (producing at the kilogram scale while employing less expensive reagents), publishing their results in 2020.[218]

Analytical methods

Several relatively simple chemical tests—commercially available as reagent testing kits—can be used to assess the presence of psilocybin in extracts prepared from mushrooms. The drug produces a yellow color in the Marquis test and a green color in the Mandelin reagent.[219] Neither of these tests is specific for psilocybin; for example, the Marquis test will react with many classes of controlled drugs, such as those containing primary amino groups and unsubstituted benzene rings, including amphetamine and methamphetamine.[220] Ehrlich's reagent and DMACA reagent are used as chemical sprays to detect the drug after thin layer chromatography.[221] Many modern techniques of analytical chemistry have been used to quantify psilocybin levels in mushroom samples. Although the earliest methods commonly used gas chromatography, the high temperature required to vaporize the psilocybin sample before analysis causes it to spontaneously lose its phosphoryl group and become psilocin, making it difficult to chemically discriminate between the two drugs. In forensic toxicology, techniques involving gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC–MS) are the most widely used due to their high sensitivity and ability to separate compounds in complex biological mixtures.[222] These techniques include ion mobility spectrometry,[223] capillary zone electrophoresis,[224] ultraviolet spectroscopy,[225] and infrared spectroscopy.[226] High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is used with ultraviolet,[217] fluorescence,[227] electrochemical,[228] and electrospray mass spectrometric detection methods.[229]

Various chromatographic methods have been developed to detect psilocin in body fluids: the rapid emergency drug identification system (REMEDi HS), a drug screening method based on HPLC;[230] HPLC with electrochemical detection;[228][231] GC–MS;[232][230] and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry.[233] Although the determination of psilocin levels in urine can be performed without sample cleanup (i.e., removing potential contaminants that make it difficult to accurately assess concentration), the analysis in plasma or serum requires preliminary extraction followed by derivatization of the extracts in the case of GC–MS. A specific immunoassay has also been developed to detect psilocin in whole blood samples.[234] A 2009 publication reported using HPLC to quickly separate forensically important illicit drugs including psilocybin and psilocin, which were identifiable within about 30 seconds of analysis time.[235] But these analytical techniques to determine psilocybin concentrations in body fluids are not routinely available and not typically used in clinical settings.[48]

Natural occurrence

| Species | % psilocybin |

|---|---|

| P. azurescens | 1.78 |

| P. serbica | 1.34 |

| P. semilanceata | 0.98 |

| P. baeocystis | 0.85 |

| P. cyanescens | 0.85 |

| P. tampanensis | 0.68 |

| P. cubensis | 0.63 |

| P. weilii | 0.61 |

| P. hoogshagenii | 0.60 |

| P. stuntzii | 0.36 |

| P. cyanofibrillosa | 0.21 |

| P. liniformans | 0.16 |

Psilocybin is present in varying concentrations in over 200 species of Basidiomycota mushrooms. In a 2000 review on the worldwide distribution of hallucinogenic mushrooms, Gastón Guzmán and colleagues considered these to be distributed amongst the following genera: Psilocybe (116 species), Gymnopilus (14), Panaeolus (13), Copelandia (12), Hypholoma (6), Pluteus (6), Inocybe (6), Conocybe (4), Panaeolina (4), Gerronema (2), and Galerina (1 species).[237] Guzmán increased his estimate of the number of psilocybin-containing Psilocybe to 144 species in a 2005 review. The majority of these are found in Mexico (53 species), with the remainder distributed in the United States and Canada (22), Europe (16), Asia (15), Africa (4), and Australia and associated islands (19).[238] The diversity of psilocybin mushrooms is reported to have been increased by horizontal transfer of the psilocybin gene cluster between unrelated mushroom species.[239][240] In general, psilocybin-containing species are dark-spored, gilled mushrooms that grow in meadows and woods of the subtropics and tropics, usually in soils rich in humus and plant debris.[214]: 5 Psilocybin mushrooms occur on all continents, but the majority of species are found in subtropical humid forests.[237] Psilocybe species commonly found in the tropics include P. cubensis and P. subcubensis. P. semilanceata—considered by Guzmán to be the world's most widely distributed psilocybin mushroom[241]—is found in Europe, North America, Asia, South America, Australia and New Zealand, but is entirely absent from Mexico.[238] Although the presence or absence of psilocybin is not of much use as a chemotaxonomical marker at the familial level or higher, it is used to classify taxa of lower taxonomic groups.[242]

Both the caps and the stems contain psychoactive compounds, although the caps consistently contain more. The spores of these mushrooms do not contain psilocybin or psilocin.[223][244][245] The total potency varies greatly between species and even between specimens of a species collected or grown from the same strain.[246] Because most psilocybin biosynthesis occurs early in the formation of fruit bodies or sclerotia, younger, smaller mushrooms tend to have a higher concentration of the drug than larger, mature mushrooms.[247] In general, the psilocybin content of mushrooms is quite variable (ranging from almost nothing to 2.5% of the dry weight)[248][49]: 248 and depends on species, strain, growth and drying conditions, and mushroom size.[236]: 36–41, 52 Cultivated mushrooms have less variability in psilocybin content than wild mushrooms.[249] The drug is more stable in dried than fresh mushrooms; dried mushrooms retain their potency for months or even years,[236]: 51–5 while mushrooms stored fresh for four weeks contain only traces of the original psilocybin.[34]

The psilocybin contents of dried herbarium specimens of Psilocybe semilanceata in one study were shown to decrease with the increasing age of the sample: collections dated 11, 33, or 118 years old contained 0.84%, 0.67%, and 0.014% (all dry weight), respectively.[250] Mature mycelia contain some psilocybin, while young mycelia (recently germinated from spores) lack appreciable amounts.[251] Many species of mushrooms containing psilocybin also contain lesser amounts of the analog compounds baeocystin and norbaeocystin,[236]: 38 chemicals thought to be biogenic precursors.[40]: 170 Although most species of psilocybin-containing mushrooms bruise blue when handled or damaged due to the oxidization of phenolic compounds, this reaction is not a definitive method of identification or determining a mushroom's potency.[246][236]: 56–58

Biosynthesis

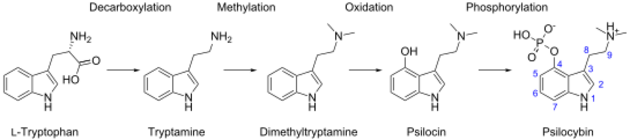

Isotopic labeling experiments from the 1960s suggested that the biosynthesis of psilocybin was a four-step process:[252]

- Decarboxylation of tryptophan to tryptamine

- N,N-Dimethylation of tryptamine at the N9 position to dimethyltryptamine

- 4-Hydroxylation of dimethyltryptamine to psilocin

- O-Phosphorylation of psilocin to psilocybin

This process can be seen in the following diagram:[253]

More recent research has demonstrated that—at least in P. cubensis—O-phosphorylation is in fact the third step, and that neither dimethyltryptamine nor psilocin are intermediates.[253] The sequence of the intermediate steps has been shown to involve four enzymes (PsiD, PsiH, PsiK, and PsiM) in P. cubensis and P. cyanescens, although it is possible that the biosynthetic pathway differs between species.[214]: 12–13 [253] These enzymes are encoded in gene clusters in Psilocybe, Panaeolus, and Gymnopilus.[240]

Escherichia coli has been genetically modified to manufacture large amounts of psilocybin.[254] Psilocybin can be produced de novo in GM yeast.[255][256]

History

Early

The use of psilocybin mushrooms in religious ceremonies dating back thousands of years is contested.[9] Despite popular narratives portraying psychedelics as ancient, widespread, and primarily used by shamans for therapeutic healing, anthropological and historical research shows their traditional use was often limited, recent, and culturally specific, with modern Western interpretations largely shaped by idealization, tourism, and ideological agendas.[9] Reliable evidence shows that psilocybin mushrooms were used ritualistically in pre-Columbian Mexico but were otherwise rare, with most claims of ancient widespread use exaggerated or misinterpreted.[9]

It has been argued that the Tassili Mushroom Figure, discovered in Tassili, Algeria, is evidence of an early psilocybin-containing mushroom cult.[257] 6,000-year-old pictographs discovered near Villar del Humo, Spain, illustrate several mushrooms that have been argued to be Psilocybe hispanica, a hallucinogenic species native to the area.[258] Some scholars have also interpreted archaeological artifacts from Mexico and the so-called Mayan "mushroom stones" of Guatemala as evidence of ritual and ceremonial use of psychoactive mushrooms in the Mayan and Aztec cultures.[236]: 11

After Spanish conquistadors of the New World arrived in the 16th century, chroniclers reported mushroom use by the natives for ceremonial and religious purposes. According to the Dominican friar Diego Durán in The History of the Indies of New Spain (published c. 1581), mushrooms were eaten in festivities conducted on the occasion of Aztec emperor Moctezuma II's accession to the throne in 1502. The Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún wrote of witnessing mushroom use in the Florentine Codex (published 1545–1590),[259]: 164 saying that some merchants celebrated upon returning from a successful business trip by consuming mushrooms to evoke revelatory visions.[260]: 118 After the defeat of the Aztecs, the Spanish forbade traditional religious practices and rituals they considered "pagan idolatry", including ceremonial mushroom use. For the next four centuries, the Indians of Mesoamerica hid their use of entheogens from the Spanish authorities.[259]: 165

Dozens of species of psychedelic mushrooms are found in Europe, but there is little documented usage of them in Old World history besides the use of Amanita muscaria among Siberian peoples.[261][262] The few existing accounts that mention psilocybin mushrooms typically lack sufficient information to allow species identification, focusing on their effects. For example, Flemish botanist Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) described the bolond gomba ("crazy mushroom"), used in rural Hungary to prepare love potions. English botanist John Parkinson included details about a "foolish mushroom" in his 1640 herbal Theatricum Botanicum.[263]: 10–12 The first reliably documented report of intoxication with Psilocybe semilanceata—Europe's most common and widespread psychedelic mushroom—involved a British family in 1799, who prepared a meal with mushrooms they had picked in London's Green Park.[263]: 16

Modern

American banker and amateur ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson and his wife, Valentina P. Wasson, a physician, studied the ritual use of psychoactive mushrooms by the native population in the Mazatec village Huautla de Jiménez, Mexico. In 1957, Wasson described the psychedelic visions he experienced during these rituals in "Seeking the Magic Mushroom", an article published in the American weekly Life magazine.[264] Later the same year they were accompanied on a follow-up expedition by French mycologist Roger Heim, who identified several of the mushrooms as Psilocybe species.[265]

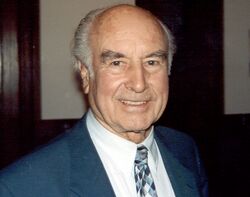

Heim cultivated the mushrooms in France and sent samples for analysis to Albert Hofmann, a chemist employed by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz. Hofmann—who had synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in 1938—led a research group that isolated and identified the psychoactive alkaloids psilocybin and psilocin from Psilocybe mexicana, publishing their results in 1958.[260]: 128 The team was aided in the discovery process by Hofmann's willingness to ingest mushroom extracts to help verify the presence of the active compounds.[260]: 126–127

Next, Hofmann's team synthesized several structural analogs of these compounds to examine how these structural changes affect psychoactivity. This research led to the development of ethocybin and CZ-74. Because these compounds' physiological effects last only about three and a half hours (about half as long as psilocybin's), they proved more manageable for use in psycholytic therapy.[49]: 237 Sandoz also marketed and sold pure psilocybin under the name Indocybin to clinicians and researchers worldwide.[259]: 166 There were no reports of serious complications when psilocybin was used in this way.[78]

In the early 1960s, Harvard University became a testing ground for psilocybin through the efforts of Timothy Leary and his associates Ralph Metzner and Richard Alpert (who later changed his name to Ram Dass). Leary obtained synthesized psilocybin from Hofmann through Sandoz Pharmaceuticals. Some studies, such as the Concord Prison Experiment, suggested promising results using psilocybin in clinical psychiatry.[50][266] But according to a 2008 review of safety guidelines in human hallucinogenic research, Leary's and Alpert's well-publicized termination from Harvard and later advocacy of hallucinogen use "further undermined an objective scientific approach to studying these compounds".[267] In response to concerns about the increase in unauthorized use of psychedelic drugs by the general public, psilocybin and other hallucinogenic drugs were unfavorably covered in the press and faced increasingly restrictive laws. In the U.S., laws passed in 1966 that prohibited the production, trade, or ingestion of hallucinogenic drugs; Sandoz stopped producing LSD and psilocybin the same year.[268] In 1970, Congress passed "The Federal Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act" that made LSD, peyote, psilocybin, and other hallucinogens illegal to use for any purpose, including scientific research.[269] United States politicians' agenda against LSD usage had swept psilocybin along with it into the Schedule I category of illicit drugs. Such restrictions on the use of these drugs in human research made funding for such projects difficult to obtain, and scientists who worked with psychedelic drugs faced being "professionally marginalized".[270] Although Hofmann tested these compounds on himself, he never advocated their legalization or medical use. In his 1979 book LSD—mein Sorgenkind (LSD—My Problem Child), he described the problematic use of these hallucinogens as inebriants.[260]: 79–116

Despite the legal restrictions on psilocybin use, the 1970s witnessed the emergence of psilocybin as the "entheogen of choice".[271]: 276 This was due in large part to wide dissemination of information on the topic, which included works such as those by Carlos Castaneda and several books that taught the technique of growing psilocybin mushrooms. One of the most popular of the latter group, Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower's Guide, was published in 1976 under the pseudonyms O. T. Oss and O. N. Oeric by Jeremy Bigwood, Dennis J. McKenna, K. Harrison McKenna, and Terence McKenna. Over 100,000 copies were sold by 1981.[272] As ethnobiologist Jonathan Ott explains, "These authors adapted San Antonio's technique (for producing edible mushrooms by casing mycelial cultures on a rye grain substrate; San Antonio 1971) to the production of Psilocybe [Stropharia] cubensis. The new technique involved the use of ordinary kitchen implements, and for the first time the layperson was able to produce a potent entheogen in his own home, without access to sophisticated technology, equipment or chemical supplies."[271]: 290 San Antonio's technique describes a method to grow the common edible mushroom Agaricus bisporus.[273]

Because of lack of clarity about laws concerning psilocybin mushrooms, specifically in the form of sclerotia (also known as "truffles"), in the late 1990s and early 2000s European retailers commercialized and marketed them in smartshops in the Netherlands, the UK, and online. Several websites[lower-alpha 5] emerged that contributed to the accessibility of information on the mushrooms' description, use, and effects, and users exchanged mushroom experiences. Since 2001, six EU countries have tightened their legislation on psilocybin mushrooms in response to concerns about their prevalence and increasing usage.[33] In the 1990s, hallucinogens and their effects on human consciousness were again the subject of scientific study, particularly in Europe. Advances in neuropharmacology and neuropsychology and the availability of brain imaging techniques have provided impetus for using drugs like psilocybin to probe the "neural underpinnings of psychotic symptom formation including ego disorders and hallucinations".[41] Recent studies in the U.S. have attracted attention from the popular press and brought psilocybin back into the limelight.[274][275]

Society and culture

Usage

A 2009 national survey of drug use by the US Department of Health and Human Services concluded that the number of first-time psilocybin mushroom users in the United States was roughly equivalent to the number of first-time users of cannabis.[276] A June 2024 report by the RAND Corporation suggests the total number of use days for psychedelics is two orders of magnitude smaller than it is for cannabis, and unlike people who use cannabis and many other drugs, infrequent users of psychedelics account for most of the total days of use.[277] The RAND Corporation report suggests psilocybin mushrooms may be the most prevalent psychedelic drug among U.S. adults.[277]

In European countries, the lifetime prevalence estimates of psychedelic mushroom usage among young adults (15–34 years) range from 0.3% to 14.1%.[278]

In modern Mexico, traditional ceremonial use survives among several indigenous groups, including the Nahuas, the Matlatzinca, the Totonacs, the Mazatecs, Mixes, Zapotecs, and the Chatino. Although hallucinogenic Psilocybe species are abundant in Mexico's low-lying areas, most ceremonial use takes places in mountainous areas of elevations greater than 1,500 meters (4,900 ft). Guzmán suggests this is a vestige of Spanish colonial influence from several hundred years earlier, when mushroom use was persecuted by the Catholic Church.[279]

Legal status

Advocacy for tolerance

Despite being illegal to possess without authorization in many Western countries, such as the UK, Australia, and some U.S. states, less conservative governments nurture the legal possession and supply of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs. In Amsterdam, authorities provide education on and promote the safe use of psychedelic drugs, such as psilocybin, to reduce public harm.[280] Similarly, religious groups like America's Uniao do Vegetal (UDV)[281] use psychedelics in traditional ceremonies.[282] A report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) notes that people may petition the DEA for exemptions to use psilocybin for religious purposes.[283]

From 1 July 2023, the Australian medicines regulator has permitted psychiatrists to prescribe psilocybin for the therapeutic treatment of treatment-resistant depression.[284]

Advocates of legalization argue there is a lack of evidence of harm,[285][286] and potential use in treating certain mental health conditions. Research is difficult to conduct because of the legal status of psychoactive substances.[287] Advocates of legalization also promote the utility of "ego dissolution"[281] and argue bans are cultural discrimination against traditional users.[288]

In 2024, after calls for regulatory and legal change to expand terminally ill populations' access to controlled substances, two legal cases related to expanded access began moving through the federal courts under right-to-try law. The Advanced Integrative Medicine Science (AIMS) Institute in concert with the NPA filed a series of lawsuits seeking both the rescheduling of and expanded right-to-try access to psilocybin.[289]

Research

Psychiatric and other disorders

Psilocybin has been a subject of clinical research since the early 1960s, when the Harvard Psilocybin Project evaluated the potential value of psilocybin as a treatment for certain personality disorders.[290] Beginning in the 2000s, psilocybin has been investigated for its possible role in the treatment of nicotine dependence, alcohol dependence, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), cluster headache, cancer-related existential distress,[218][291] anxiety disorders, and certain mood disorders.[259]: 179–81 [292][293] It is also being studied in people with Parkinson's disease.[294][295] In 2018, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted breakthrough therapy designation for psilocybin-assisted therapy for treatment-resistant depression.[296][297] A systematic review published in 2021 found that the use of psilocybin as a pharmaceutical substance was associated with reduced intensity of depression symptoms.[298] The role of psilocybin as a possible psychoplastogen is also being examined.[175][176][177] It is under development by Compass Pathways, Cybin, and several other companies.[299][300]

Depression

Clinical trials, including both open-label trials and double-blind randomized controlled trials (RCTs), have found that single doses of psilocybin produce rapid and long-lasting antidepressant effects outperforming placebo in people with major depressive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.[301] Combined with brief psychological support in a Phase II trial, it has been found to produce dose-dependent improvements in depressive symptoms, with 25 mg (a moderate dose) more effective than 10 mg (a low dose), and 10 mg more effective than 1 mg (non-psychoactive and equivalent to placebo).[301][302] The antidepressant effects of psilocybin with psychological support have been found to last at least 6 weeks following a single dose.[301][302][303][304]

However, some trials have not found psilocybin to significantly outperform placebo in the treatment of depression.[301] In addition, a Phase II trial found that two 25 mg doses of psilocybin 3 weeks apart versus daily treatment with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) escitalopram (Lexapro) for 6 weeks (plus two putatively non-psychoactive 1 mg doses of psilocybin 3 weeks apart) did not show a statistically significant difference in reduction of depressive symptoms between groups.[301][305] However, reductions in depressive symptoms were numerically greater with psilocybin, some secondary measures favored psilocybin, and the rate of remission was statistically higher with psilocybin (57% with psilocybin vs. 28% with escitalopram).[301][305] In any case, the antidepressant effect size of psilocybin over escitalopram appears to be small.[306]

Functional unblinding by their psychoactive effects and positive psychological expectancy effects (i.e., the placebo effect) are major limitations and sources of bias of clinical trials of psilocybin and other psychedelics for treatment of depression.[307][308][309][310] Relatedly, most of the therapeutic benefit of conventional antidepressants like the SSRIs for depression appears to be attributable to the placebo response.[311][312] It has been proposed that psychedelics like psilocybin may in fact act as active "super placebos" when used for therapeutic purposes.[313][314] Psilocybin has not received regulatory approval for medical use in the United States.[15][301][87]

In a 2024 meta-analysis of RCTs of psychedelics and escitalopram for treatment of depression, only "high-dose" psilocybin (≥20 mg) significantly outperformed escitalopram in improving depressive symptoms.[306] It showed a large effect size over placebo, but a small effect size over escitalopram.[306] A 2025 meta-analysis found a moderate effect size advantage of psilocybin relative to placebo.[315] A 2024 network meta-analysis of RCTs of therapies for treatment-resistant depression, with effectiveness measures being response and remission rates, likewise found that psilocybin was more effective than placebo and, considering both effectiveness and tolerability or safety, recommended it as a first-line therapy, along with ketamine, esketamine, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[316] However, the quality of evidence was generally rated as low or very low.[316] Meta-analyses of psychedelics for depression and other psychiatric conditions have found that psilocybin has the greatest number of studies and the most evidence of benefit, relative to other psychedelics like ayahuasca and LSD.[306][317][87][318]