Logical conjunction

| AND | |

|---|---|

| |

| Definition | [math]\displaystyle{ xy }[/math] |

| Truth table | [math]\displaystyle{ (1000) }[/math] |

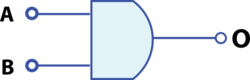

| Logic gate | |

| Normal forms | |

| Disjunctive | [math]\displaystyle{ xy }[/math] |

| Conjunctive | [math]\displaystyle{ xy }[/math] |

| Zhegalkin polynomial | [math]\displaystyle{ xy }[/math] |

| white;">Post's lattices | |

| 0-preserving | yes |

| 1-preserving | yes |

| Monotone | no |

| Affine | no |

In logic, mathematics and linguistics, and ([math]\displaystyle{ \wedge }[/math]) is the truth-functional operator of conjunction or logical conjunction. The logical connective of this operator is typically represented as [math]\displaystyle{ \wedge }[/math][1] or [math]\displaystyle{ \& }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] (prefix) or [math]\displaystyle{ \times }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \cdot }[/math][2] in which [math]\displaystyle{ \wedge }[/math] is the most modern and widely used.

The and of a set of operands is true if and only if all of its operands are true, i.e., [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math] is true if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is true and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is true.

An operand of a conjunction is a conjunct.

Beyond logic, the term "conjunction" also refers to similar concepts in other fields:

- In natural language, the denotation of expressions such as English "and";

- In programming languages, the short-circuit and control structure;

- In set theory, intersection.

- In lattice theory, logical conjunction (greatest lower bound).

Notation

And is usually denoted by an infix operator: in mathematics and logic, it is denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ \wedge }[/math] (Unicode U+2227 ∧ LOGICAL AND),[1] [math]\displaystyle{ \& }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \times }[/math]; in electronics, [math]\displaystyle{ \cdot }[/math]; and in programming languages, &, &&, or and. In Jan Łukasiewicz's prefix notation for logic, the operator is [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math], for Polish koniunkcja.[3]

Definition

Logical conjunction is an operation on two logical values, typically the values of two propositions, that produces a value of true if and only if (also known as iff) both of its operands are true.[2][1]

The conjunctive identity is true, which is to say that AND-ing an expression with true will never change the value of the expression. In keeping with the concept of vacuous truth, when conjunction is defined as an operator or function of arbitrary arity, the empty conjunction (AND-ing over an empty set of operands) is often defined as having the result true.

Truth table

The truth table of [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math]:[1][2]

| [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ A \wedge B }[/math] |

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | False |

| False | False | False |

Defined by other operators

In systems where logical conjunction is not a primitive, it may be defined as[4]

- [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B = \neg(A \to \neg B) }[/math]

or

- [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B = \neg(\neg A \lor \neg B). }[/math]

Introduction and elimination rules

As a rule of inference, conjunction introduction is a classically valid, simple argument form. The argument form has two premises, [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]. Intuitively, it permits the inference of their conjunction.

- [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

- Therefore, A and B.

or in logical operator notation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vdash A \land B }[/math]

Here is an example of an argument that fits the form conjunction introduction:

- Bob likes apples.

- Bob likes oranges.

- Therefore, Bob likes apples and Bob likes oranges.

Conjunction elimination is another classically valid, simple argument form. Intuitively, it permits the inference from any conjunction of either element of that conjunction.

- [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

- Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math].

...or alternatively,

- [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

- Therefore, [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

In logical operator notation:

- [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vdash A }[/math]

...or alternatively,

- [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \vdash B }[/math]

Negation

Definition

A conjunction [math]\displaystyle{ A\land B }[/math] is proven false by establishing either [math]\displaystyle{ \neg A }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \neg B }[/math]. In terms of the object language, this reads

- [math]\displaystyle{ \neg A\to\neg(A\land B) }[/math]

This formula can be seen as a special case of

- [math]\displaystyle{ (A\to C) \to ( (A\land B)\to C ) }[/math]

when [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is a false proposition.

Other proof strategies

If [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] implies [math]\displaystyle{ \neg B }[/math], then both [math]\displaystyle{ \neg A }[/math] as well as [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] prove the conjunction false:

- [math]\displaystyle{ (A\to\neg{}B)\to\neg(A\land B) }[/math]

In other words, a conjunction can actually be proven false just by knowing about the relation of its conjuncts, and not necessary about their truth values.

This formula can be seen as a special case of

- [math]\displaystyle{ (A\to(B\to C))\to ( (A\land B)\to C ) }[/math]

when [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] is a false proposition.

Either of the above are constructively valid proofs by contradiction.

Properties

commutativity: yes

| [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \Leftrightarrow }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ B \land A }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \Leftrightarrow }[/math] |

associativity: yes

distributivity: with various operations, especially with or

| others |

|---|

|

with exclusive or: with material nonimplication: with itself: |

idempotency: yes

monotonicity: yes

truth-preserving: yes

When all inputs are true, the output is true.

| [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \Rightarrow }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \Rightarrow }[/math] | ||

| (to be tested) |

falsehood-preserving: yes

When all inputs are false, the output is false.

| [math]\displaystyle{ A \land B }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ \Rightarrow }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ A \lor B }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \Rightarrow }[/math] | ||

| (to be tested) |

Walsh spectrum: (1,-1,-1,1)

Nonlinearity: 1 (the function is bent)

If using binary values for true (1) and false (0), then logical conjunction works exactly like normal arithmetic multiplication.

Applications in computer engineering

In high-level computer programming and digital electronics, logical conjunction is commonly represented by an infix operator, usually as a keyword such as "AND", an algebraic multiplication, or the ampersand symbol & (sometimes doubled as in &&). Many languages also provide short-circuit control structures corresponding to logical conjunction.

Logical conjunction is often used for bitwise operations, where 0 corresponds to false and 1 to true:

0 AND 0=0,0 AND 1=0,1 AND 0=0,1 AND 1=1.

The operation can also be applied to two binary words viewed as bitstrings of equal length, by taking the bitwise AND of each pair of bits at corresponding positions. For example:

11000110 AND 10100011=10000010.

This can be used to select part of a bitstring using a bit mask. For example, 10011101 AND 00001000 = 00001000 extracts the fourth bit of an 8-bit bitstring.

In computer networking, bit masks are used to derive the network address of a subnet within an existing network from a given IP address, by ANDing the IP address and the subnet mask.

Logical conjunction "AND" is also used in SQL operations to form database queries.

The Curry–Howard correspondence relates logical conjunction to product types.

Set-theoretic correspondence

The membership of an element of an intersection set in set theory is defined in terms of a logical conjunction: [math]\displaystyle{ x\in A\cap B }[/math] if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ (x\in A)\wedge (x\in B) }[/math]. Through this correspondence, set-theoretic intersection shares several properties with logical conjunction, such as associativity, commutativity and idempotence.

Natural language

As with other notions formalized in mathematical logic, the logical conjunction and is related to, but not the same as, the grammatical conjunction and in natural languages.

English "and" has properties not captured by logical conjunction. For example, "and" sometimes implies order having the sense of "then". For example, "They got married and had a child" in common discourse means that the marriage came before the child.

The word "and" can also imply a partition of a thing into parts, as "The American flag is red, white, and blue." Here, it is not meant that the flag is at once red, white, and blue, but rather that it has a part of each color.

See also

- And-inverter graph

- AND gate

- Bitwise AND

- Boolean algebra

- Boolean conjunctive query

- Boolean domain

- Boolean function

- Boolean-valued function

- Conjunction elimination

- Conjunction (grammar)

- De Morgan's laws

- First-order logic

- Fréchet inequalities

- List of Boolean algebra topics

- Logical disjunction

- Logical graph

- Negation

- Operation

- Peano–Russell notation

- Propositional calculus

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "2.2: Conjunctions and Disjunctions" (in en). 2019-08-13. https://math.libretexts.org/Courses/Monroe_Community_College/MTH_220_Discrete_Math/2%3A_Logic/2.2%3A_Conjunctions_and_Disjunctions.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Conjunction, Negation, and Disjunction". https://philosophy.lander.edu/logic/conjunct.html.

- ↑ Józef Maria Bocheński (1959), A Précis of Mathematical Logic, translated by Otto Bird from the French and German editions, Dordrecht, South Holland: D. Reidel, passim.

- ↑ Smith, Peter. "Types of proof system". p. 4. http://www.logicmatters.net/resources/pdfs/ProofSystems.pdf.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Conjunction", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/c025080

- Wolfram MathWorld: Conjunction

- "Property and truth table of AND propositions". http://www.math.hawaii.edu/~ramsey/Logic/And.html.

|