Biology:p300-CBP coactivator family

| E1A binding protein p300 | |

|---|---|

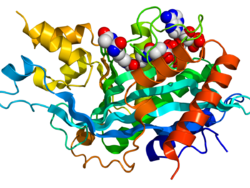

Crystallographic structure of the histone acetyltransferase domain of EP300 (rainbow colored, N-terminus = blue, C-terminus = red) complexed with the inhibitor lysine-CoA (space-filling model, carbon = white, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue, phosphorus = orange).[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | EP300 |

| Alt. symbols | p300 |

| NCBI gene | 2033 |

| HGNC | 3373 |

| OMIM | 602700 |

| PDB | 3biy |

| RefSeq | NM_001429 |

| UniProt | Q09472 |

| Other data | |

| EC number | 2.3.1.48 |

| Locus | Chr. 22 q13.2 |

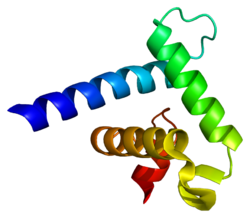

| CREB binding protein (CBP) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | CREBBP |

| Alt. symbols | CBP, RSTS |

| NCBI gene | 1387 |

| HGNC | 2348 |

| OMIM | 600140 |

| PDB | 3dwy |

| RefSeq | NM_004380 |

| UniProt | Q92793 |

| Other data | |

| EC number | 2.3.1.48 |

| Locus | Chr. 16 p13.3 |

The p300-CBP coactivator family in humans is composed of two closely related transcriptional co-activating proteins (or coactivators):

- p300 (also called EP300 or E1A binding protein p300)

- CBP (also known as CREB-binding protein or CREBBP)

Both p300 and CBP interact with numerous transcription factors and act to increase the expression of their target genes.[2][3]

Protein structure

p300 and CBP have similar structures. Both contain five protein interaction domains: the nuclear receptor interaction domain (RID), the KIX domain (CREB and MYB interaction domain), the cysteine/histidine regions (TAZ1/CH1 and TAZ2/CH3) and the interferon response binding domain (IBiD). The last four domains, KIX, TAZ1, TAZ2 and IBiD of p300, each bind tightly to a sequence spanning both transactivation domains 9aaTADs of transcription factor p53.[4] In addition p300 and CBP each contain a protein or histone acetyltransferase (PAT/HAT) domain and a bromodomain that binds acetylated lysines and a PHD finger motif with unknown function.[5] The conserved domains are connected by long stretches of unstructured linkers.

Regulation of gene expression

p300 and CBP are thought to increase gene expression in three ways:

- by relaxing the chromatin structure at the gene promoter through their intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity.[6]

- recruiting the basal transcriptional machinery including RNA polymerase II to the promoter.

- acting as adaptor molecules.[7]

p300 regulates transcription by directly binding to transcription factors (see external reference for explanatory image). This interaction is managed by one or more of the p300 domains: the nuclear receptor interaction domain (RID), the CREB and MYB interaction domain (KIX), the cysteine/histidine regions (TAZ1/CH1 and TAZ2/CH3) and the interferon response binding domain (IBiD). The last four domains, KIX, TAZ1, TAZ2 and IBiD of p300, each bind tightly to a sequence spanning both transactivation domains 9aaTADs of transcription factor p53.[8]

Enhancer regions, which regulate gene transcription, are known to be bound by p300 and CBP, and ChIP-seq for these proteins has been used to predict enhancers.[9][10][11][12]

Work done by Heintzman and colleagues[13] showed that 70% of the p300 binding occurs in open chromatin regions as seen by the association with DNase I hypersensitive sites. Furthermore, they have described that most p300 binding (75%) occurs far away from transcription start sites (TSSs) and these binding sites are also associated with enhancer regions as seen by H3K4me1 enrichment. They have also found some correlation between p300 and RNAPII binding at enhancers, which can be explained by the physical interaction with promoters or by enhancer RNAs.

Function in G protein signaling

An example of a process involving p300 and CBP is G protein signaling. Some G proteins stimulate adenylate cyclase that results in elevation of cAMP. cAMP stimulates PKA, which consists of four subunits, two regulatory and two catalytic. Binding of cAMP to the regulatory subunits causes release of the catalytic subunits. These subunits can then enter the nucleus to interact with transcriptional factors, thus affecting gene transcription. The transcription factor CREB, which interacts with a DNA sequence called a cAMP response element (or CRE), is phosphorylated on a serine (Ser 133) in the KID domain. This modification is PKA mediated, and promotes the interaction of the KID domain of CREB with the KIX domain of CBP or p300 and enhances transcription of CREB target genes, including genes that aid gluconeogenesis. This pathway can be initiated by adrenaline activating β-adrenergic receptors on the cell surface.[14]

Clinical significance

Mutations in CBP, and to a lesser extent p300, are the cause of Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome,[15] which is characterized by severe mental retardation. These mutations result in the loss of one copy of the gene in each cell, which reduces the amount of CBP or p300 protein by half. Some mutations lead to the production of a very short, nonfunctional version of the CBP or p300 protein, while others prevent one copy of the gene from making any protein at all. Although researchers do not know how a reduction in the amount of CBP or p300 protein leads to the specific features of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, it is clear that the loss of one copy of the CBP or p300 gene disrupts normal development.

Defects in CBP HAT activity appears to cause problems in long-term memory formation.[16]

CBP and p300 have also been found to be involved in multiple rare chromosomal translocations that are associated with acute myeloid leukemia.[7] For example, researchers have found a translocation between chromosomes 8 and 22 (in the region containing the p300 gene) in several people with a cancer of blood cells called acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Another translocation, involving chromosomes 11 and 22, has been found in a small number of people who have undergone cancer treatment. This chromosomal change is associated with the development of AML following chemotherapy for other forms of cancer.

Mutations in the p300 gene have been identified in several other types of cancer. These mutations are somatic, which means they are acquired during a person's lifetime and are present only in certain cells. Somatic mutations in the p300 gene have been found in a small number of solid tumors, including cancers of the colon and rectum, stomach, breast and pancreas. Studies suggest that p300 mutations may also play a role in the development of some prostate cancers, and could help predict whether these tumors will increase in size or spread to other parts of the body. In cancer cells, p300 mutations prevent the gene from producing any functional protein. Without p300, cells cannot effectively restrain growth and division, which can allow cancerous tumors to form.

Mouse models

CBP and p300 are critical for normal embryonic development, as mice completely lacking either CBP or p300 protein, die at an early embryonic stage.[17][18] In addition, mice which lack one functional copy (allele) of both the CBP and p300 genes (i.e. are heterozygous for both CBP and p300) and thus have half of the normal amount of both CBP and p300, also die early in embryogenesis.[17] This indicates that the total amount of CBP and p300 protein is critical for embryo development. Data suggest that some cell types can tolerate loss of CBP or p300 better than the whole organism can. Mouse B cells or T cells lacking either CBP and p300 protein develop fairly normally, but B or T cells that lack both CBP and p300 fail to develop in vivo.[2][19] Together, the data indicate that, while individual cell types require different amounts of CBP and p300 to develop or survive and some cell types are more tolerant of loss of CBP or p300 than the whole organism, it appears that many, if not all cell types may require at least some p300 or CBP to develop.

References

- ↑ PDB: 3BIY; "The structural basis of protein acetylation by the p300/CBP transcriptional coactivator". Nature 451 (7180): 846–50. Feb 2008. doi:10.1038/nature06546. PMID 18273021. Bibcode: 2008Natur.451..846L.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Conditional knockout mice reveal distinct functions for the global transcriptional coactivators CBP and p300 in T-cell development". Molecular and Cellular Biology 26 (3): 789–809. Feb 2006. doi:10.1128/MCB.26.3.789-809.2006. PMID 16428436.

- ↑ "CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (17): 13505–8. Apr 2001. doi:10.1074/jbc.R000025200. PMID 11279224.

- ↑ The prediction for 9aaTADs (for both acidic and hydrophilic transactivation domains) is available online from ExPASy http://us.expasy.org/tools/ and EMBnet Spain "EMBnet Austria: Detect 9aaTAD Pattern". http://www.es.embnet.org/Services/EMBnetAT/htdoc/9aatad/.

- ↑ "Biological control through regulated transcriptional coactivators". Cell 119 (2): 157–67. Oct 2004. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.037. PMID 15479634.

- ↑ "Distinct roles of GCN5/PCAF-mediated H3K9ac and CBP/p300-mediated H3K18/27ac in nuclear receptor transactivation". The EMBO Journal 30 (2): 249–62. Jan 2011. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.318. PMID 21131905.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development". Genes & Development 14 (13): 1553–77. Jul 2000. doi:10.1101/gad.14.13.1553. PMID 10887150.

- ↑ "Four domains of p300 each bind tightly to a sequence spanning both transactivation subdomains of p53". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (17): 7009–14. Apr 2007. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702010104. PMID 17438265. Bibcode: 2007PNAS..104.7009T.; "Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain: establishment and prediction utilities". Genomics 89 (6): 756–68. Jun 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.02.003. PMID 17467953.

- ↑ "Genome-wide mapping of HATs and HDACs reveals distinct functions in active and inactive genes". Cell 138 (5): 1019–31. Sep 2009. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.049. PMID 19698979.

- ↑ "Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression". Nature 459 (7243): 108–12. May 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07829. PMID 19295514. Bibcode: 2009Natur.459..108H.

- ↑ "ChIP-seq accurately predicts tissue-specific activity of enhancers". Nature 457 (7231): 854–8. Feb 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07730. PMID 19212405. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457..854V.

- ↑ "ChIP-Seq identification of weakly conserved heart enhancers". Nature Genetics 42 (9): 806–10. Sep 2010. doi:10.1038/ng.650. PMID 20729851.

- ↑ "Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome". Nature Genetics 39 (3): 311–8. Mar 2007. doi:10.1038/ng1966. PMID 17277777.

- ↑ "Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 2 (8): 599–609. Aug 2001. doi:10.1038/35085068. PMID 11483993.

- ↑ "Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome caused by mutations in the transcriptional co-activator CBP". Nature 376 (6538): 348–51. Jul 1995. doi:10.1038/376348a0. PMID 7630403. Bibcode: 1995Natur.376..348P.

- ↑ "CBP histone acetyltransferase activity is a critical component of memory consolidation". Neuron 42 (6): 961–72. Jun 2004. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.002. PMID 15207240.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Gene dosage-dependent embryonic development and proliferation defects in mice lacking the transcriptional integrator p300". Cell 93 (3): 361–72. May 1998. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81165-4. PMID 9590171.

- ↑ "Extensive brain hemorrhage and embryonic lethality in a mouse null mutant of CREB-binding protein". Mechanisms of Development 95 (1–2): 133–45. Jul 2000. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(00)00360-9. PMID 10906457.

- ↑ "Global transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein and p300 are highly essential collectively but not individually in peripheral B cells". Blood 107 (11): 4407–16. Jun 2006. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-08-3263. PMID 16424387.

External links

- p300-CBP Transcription Factors at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- NURSA C39

- NURSA C54

- p300-CBP regulatory mechanism in the IFN-β enhanceosome complex

|