Chemistry:Calcifediol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

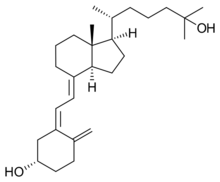

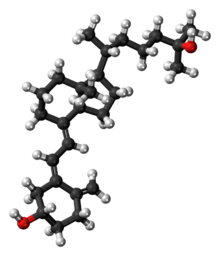

| Preferred IUPAC name

(1S,3Z)-3-[(2E)-2-{(1R,3aS,7aR)-1-[(2R)-6-Hydroxy-6-methylheptan-2-yl]-7a-methyloctahydro-4H-inden-4-ylidene}ethylidene]-4-methylidenecyclohexan-1-ol | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Calcifediol |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H44O2 | |

| Molar mass | 400.64 g/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| 1=ATC code }} | H05BX05 (WHO) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Calcifediol, also known as calcidiol, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, or 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 (abbreviated 25(OH)D3),[1] is a form of vitamin D produced in the liver by hydroxylation of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) by the enzyme vitamin D 25-hydroxylase.[2][3][4] Calcifediol can be further hydroxylated by the enzyme 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase, primarily in the kidney, to form calcitriol (1,25-(OH)2D3), which is the active hormonal form of vitamin D.[2][3][4]

Calcifediol is strongly bound in blood by the vitamin D-binding protein.[4] Measurement of serum calcifediol is the usual test performed to determine a person's vitamin D status, to show vitamin D deficiency or sufficiency.[3][4] Calcifediol is available as an oral medication in some countries to supplement vitamin D status.[3][5][6]

Biology

Calcifediol is the precursor for calcitriol, the active form of vitamin D.[2][3] It is synthesized in the liver, by hydroxylation of cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) at the 25-position.[2] This enzymatic 25-hydroxylase reaction is mostly due to the actions of CYP2R1, present in microsomes, although other enzymes such as mitochondrial CYP27A1 can contribute.[4][7] Variations in the expression and activity of CYP2R1, such as low levels in obesity, affect circulating calcifediol.[7] Similarly, vitamin D2, ergocalciferol, can also be 25-hydroxylated to form 25-hydroxyergocalciferol, (ercalcidiol, 25(OH)D2);[1] both forms are measured together in blood as 25(OH)D.[2][3]

At a typical intake of cholecalciferol (up to 2000 IU/day), conversion to calcifediol is rapid. When large doses are given (100,000 IU), it takes 7 days to reach peak calcifediol concentrations.[8] Calcifediol binds in the blood to vitamin D-binding protein (also known as gc-globulin) and is the main circulating vitamin D metabolite.[3][4] Calcifediol has an elimination half-life of around 15 to 30 days.[3][8]

Calcifediol is further hydroxylated at the 1-alpha-position in the kidneys to form 1,25-(OH)2D3, calcitriol.[2][3] This enzymatic 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase reaction is performed exclusively by CYP27B1, which is highly expressed in the kidneys where it is principally regulated by parathyroid hormone, but also by FGF23 and calcitriol itself.[2][4][7] CYP27B1 is also expressed in a number of other tissues, including macrophages, monocytes, keratinocytes, placenta and parathyroid gland and extra-renal synthesis of calcitriol from calcifediol has been shown to have biological effects in these tissues.[7][9]

Calcifediol is also converted into 24,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol by 24-hydroxylation.[2] This enzymatic reaction is performed by CYP24A1 which is expressed in many vitamin D target tissues including kidney, and is induced by calcitriol.[4] This will inactivate calcitriol to calcitroic acid, but 24,25-(OH)2D3 may have some biological actions itself.[4]

Blood test for vitamin D deficiency

In medical practice, a blood test for 25-hydroxy-vitamin D, 25(OH)D, is used to determine an individual's vitamin D status.[10] The name 25(OH)D refers to any combination of calcifediol (25-hydroxy-cholecalciferol), derived from vitamin D3, and ercalcidiol (25-hydroxy-ergocalciferol),[1] derived from vitamin D2. The first of these (also known as 25-hydroxy vitamin D3) is made by the body, or is sourced from certain animal foods or cholecalciferol supplements. The second (25-hydroxy vitamin D2) is from certain vegetable foods or ergocalciferol supplements.[10] Clinical tests for 25(OH)D often measure the total level of both of these two compounds together, generally without differentiating.[11]

This measurement is considered the best indicator of overall vitamin D status.[10][12][13] US labs generally report 25(OH)D levels as ng/mL. Other countries use nmol/L. Multiply ng/mL by 2.5 to convert to nmol/L.[3]

This test can be used to diagnose vitamin D deficiency, and is performed in people with high risk for vitamin D deficiency, when the results of the test can be used to support beginning replacement therapy with vitamin D supplements.[3][14] Patients with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption, obesity, and some other infections may be at greater risk for being vitamin D-deficient and so are more likely to have this test.[14] Although vitamin D deficiency is common in some populations including those living at higher latitudes or with limited sun exposure, the 25(OH)D test is not usually requested for the entire population.[14] Physicians may advise low risk patients to take over-the-counter vitamin D supplements in place of having screening.[14]

It is the most sensitive measure, though experts have called for improved standardization and reproducibility across different laboratories.[3][12] According to MedlinePlus, the recommended range of 25(OH)D is 20 to 40 ng/mL (50 to 100 nmol/L) though they recognize many experts recommend 30 to 50 ng/mL (75 to 125 nmol/L).[10] The normal range varies widely depending on several factors, including age and geographic location. A broad reference range of 20 to 150 nmol/L (8-60 ng/mL) has also been suggested,[15] while other studies have defined levels below 80 nmol/L (32 ng/mL) as indicative of vitamin D deficiency.[16]

Increasing calcifediol levels up to levels of 80 nmol/L (32 ng/mL) are associated with increasing the fraction of calcium that is absorbed from the gut.[12] Urinary calcium excretion balances intestinal calcium absorption and does not increase with calcifediol levels up to ~400 nmol/L (160 ng/mL).[17]

Supplementation

Calcifediol supplements have been used in some studies to improve vitamin D status.[3] Indications for their use include vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency, refractory rickets (vitamin D resistant rickets), familial hypophosphatemia, hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia and renal osteodystrophy and, with calcium, in primary or corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis.[18]

Calcifediol may have advantages over cholecalciferol for the correction of vitamin D deficiency states.[5] A review of the results of nine randomized control trials which compared oral doses of both, found that calcifediol was 3.2-fold more potent than cholecalciferol.[5] Calcifediol is better absorbed from the intestine and has greater affinity for the vitamin-D-binding protein, both of which increase its bioavailability.[19] Orally administered calcifediol has a much shorter half-life with faster elimination.[19] These properties may be beneficial in people with intestinal malabsorption, obesity, or treated with certain other medications.[19]

In 2016, the FDA approved a formulation of calcifediol (Rayaldee) 60 microgram daily as a prescription medication to treat secondary hyperparathyroidism in patients with chronic kidney disease.[6]

Interactive pathway map

History

Research in the laboratory of Hector DeLuca identified 25(OH)D in 1968 and showed that the liver was necessary for its formation.[20] The enzyme responsible for this synthesis, cholecalciferol 25-hydroxylase, was isolated in the same laboratory by Michael F. Holick in 1972.[21]

Research

Studies are ongoing comparing the effects of calcifediol with other forms of vitamin D including cholecalciferol in prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.[2][19]

See also

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Hypovitaminosis D

- Vitamin D

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN): Nomenclature of vitamin D. Recommendations 1981". European Journal of Biochemistry 124 (2): 223–7. May 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06581.x. PMID 7094913.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "Vitamin D". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 11 February 2021. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/vitamin-D.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D" (in en). 9 October 2020. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 "Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications". Chemistry & Biology 21 (3): 319–29. March 2014. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. PMID 24529992.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Is calcifediol better than cholecalciferol for vitamin D supplementation?". Osteoporosis International 29 (8): 1697–1711. August 2018. doi:10.1007/s00198-018-4520-y. PMID 29713796.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Rayaldee (calcifediol) FDA Approval History - Drugs.com". https://www.drugs.com/history/rayaldee.html. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Vitamin D Metabolism Revised: Fall of Dogmas". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 34 (11): 1985–1992. November 2019. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3884. PMID 31589774.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "25-Hydroxylation of vitamin D3: relation to circulating vitamin D3 under various input conditions". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 87 (6): 1738–42. June 2008. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1738. PMID 18541563.

- ↑ "Extrarenal expression of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1-hydroxylase". Arch Biochem Biophys 523 (1): 95–102. July 2012. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.016. PMID 22446158.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "25-hydroxy vitamin D test: Medline Plus". Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ "25HDN - Clinical: 25-Hydroxyvitamin D2 and D3, Serum". Mayo Clinic Labs. 2021. https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/Clinical+and+Interpretive/83670. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Functional indices of vitamin D status and ramifications of vitamin D deficiency". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 80 (6 Suppl): 1706S–9S. December 2004. doi:10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1706S. PMID 15585791.

- ↑ "Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials". BMJ 348: g2035. April 2014. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2035. PMID 24690624.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 American Society for Clinical Pathology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation (American Society for Clinical Pathology), http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-society-for-clinical-pathology/, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- "Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: costly, confusing, and without credibility". Lancet 379 (9811): 95–6. January 2012. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61816-3. PMID 22243814.

- "The rising cost of vitamin D testing in Australia: time to establish guidelines for testing". The Medical Journal of Australia 197 (2): 90. July 2012. doi:10.5694/mja12.10561. PMID 22794049.

- "Pathology consultation on vitamin D testing: clinical indications for 25(OH) vitamin D measurement". American Journal of Clinical Pathology (American Society for Clinical Pathology) 137 (5): 831–2. May 2012. doi:10.1309/ajcp2gp0ghkqrcoe. PMID 22645788., which cites

- "The measurement of vitamin D3 requires maintaining quality control". American Journal of Clinical Pathology 137 (5): 832; author reply 833. May 2012. doi:10.1309/AJCP2GP0GHKQRCOE. PMID 22523224.

- "Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 96 (7): 1911–30. July 2011. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385. PMID 21646368.

- ↑ Bender, David A. (2003). "Vitamin D". Nutritional biochemistry of the vitamins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80388-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=pxEJNs0IUo4C. Retrieved December 10, 2008 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ "Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D". The Journal of Nutrition 135 (2): 317–22. February 2005. doi:10.1093/jn/135.2.317. PMID 15671234.

- ↑ "Safety of vitamin D3 in adults with multiple sclerosis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 86 (3): 645–51. September 2007. doi:10.1093/ajcn/86.3.645. PMID 17823429.

- ↑ "Calcifediol". https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00146.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Hypovitaminosis D: Is It Time to Consider the Use of Calcifediol?". Nutrients 11 (5): 1016. May 2019. doi:10.3390/nu11051016. PMID 31064117.

- ↑ ""Activation" of vitamin D by the liver". The Journal of Clinical Investigation 48 (11): 2032–7. November 1969. doi:10.1172/JCI106168. PMID 4310770.

- ↑ "Isolation and identification of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol from human plasma". Archives of Internal Medicine 129 (1): 56–61. January 1972. doi:10.1001/archinte.1972.00320010060005. PMID 4332591.

External links

- "Calcifediol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/rn/19356-17-3.

|