Medicine:Frontotemporal dementia

| Frontotemporal dementia | |

|---|---|

| |

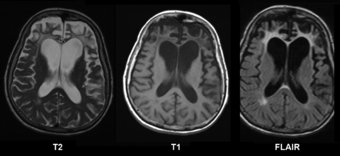

| Brain MRI of a 65-year-old female person with frontotemporal dementia. Cortical and white matter atrophy of the frontal lobes is clear in all images. | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

| Causes | frontotemporal lobar degeneration |

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), or frontotemporal degeneration disease,[1] or frontotemporal neurocognitive disorder,[2] encompasses several types of dementia involving the progressive degeneration of frontal and temporal lobes.[3] FTDs broadly present as behavioral or language disorders with gradual onsets.[4] Common signs and symptoms include significant changes in social and personal behavior, apathy, blunting of emotions, and deficits in both expressive and receptive language. Currently, there is no cure for FTD, but there are treatments that help alleviate symptoms.

Frontotemporal dementias are mostly early-onset syndromes that are linked to frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD),[5] which is characterized by progressive neuronal loss predominantly involving the frontal or temporal lobes, and a typical loss of more than 70% of spindle neurons, while other neuron types remain intact.[6] The three main subtypes or variant syndromes are a behavioral variant (bvFTD) previously known as Pick's disease,[7][8] and two variants of primary progressive aphasia – semantic variant (svPPA), and nonfluent variant (nfvPPA).[4][8] Two rare distinct subtypes of FTD are neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID), and basophilic inclusion body disease. Other related disorders include corticobasal syndrome and FTD with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), FTD-ALS, also called FTD-MND.[9]

Signs and symptoms tend to appear in late adulthood, typically between the ages of 45 and 65.[10] Men and women appear to be equally affected.[9] FTD is the second most prevalent type of early onset dementia after Alzheimer's disease.[9][11] Considered individually, each of the subtypes is relatively rare.[11]

Features of FTD were first described by Arnold Pick between 1892 and 1906.[12] The name Pick's disease was coined in 1922.[13] This term is now reserved only for the behavioral variant of FTD which shows the presence of the characteristic Pick bodies and Pick cells[14][15] first described by Alois Alzheimer in 1911.[13]

Signs and symptoms

Frontotemporal dementia is an early-onset disorder that mostly occurs between the ages of 45 and 65, but can begin earlier, and in 20–25% of cases onset is later.[5][16] It is the most common early presenting dementia.[17]

The International Classification of Diseases recognizes the disease as causative to disorder affecting mental and behavioural aspects of the human organism. Dissociation from family, compulsive buying disorder (oniomania), vulgar speech characteristics, screaming, inability to control emotions, behavior, personality, and temperament are characteristic social display patterns.[18] A gradual onset and progression of changes in behavior or language deficits are reported to have begun several years prior to presentation to a neurologist.[9]

The main subtypes of frontotemporal dementia are behavioral variant FTD, semantic dementia, progressive nonfluent aphasia, and FTD associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (FTD–ALS). Two distinct rare subtypes are neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease, and basophilic inclusion body disease. Related disorders are corticobasal syndrome, and progressive supranuclear palsy.[9]

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (BvFTD) was previously known as Pick's disease, and is the most common of the FTD types.[7] BvFTD is diagnosed four times as often as the PPA variants.[19] Behavior can change in BvFTD in either of two ways—it can change to being impulsive and disinhibited, acting in socially unacceptable ways; or it can change to being listless and apathetic.[20][21] About 12–13% of people with bvFTD develop motor neuron disease.[22]

The Pick bodies in behavioral variant FTD are spherical inclusion bodies found in the cytoplasm of affected cells. They consist of tau fibrils as a major component together with a number of other protein products including ubiquitin and tubulin.[23]

Semantic dementia

Semantic dementia (SD) is characterized by the loss of semantic understanding, resulting in impaired word comprehension. However, speech remains fluent and grammatical.[21]

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

Progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) is characterized by progressive difficulties in speech production.[21]

Neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease

Neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID) is a rare distinct variant. The inclusion bodies that are present in NIFID are cytoplasmic and made up of type IV intermediate filaments.[24][25] NIFID has an early age of onset between 23 and 56. Symptoms can include behavioural, and personality changes, memory and cognitive impairments, language difficulties, motor weakness, and extrapyramidal symptoms.[24] NIFID is one of the FTLD-FUS proteopathies.[25] Imaging commonly shows atrophy in the frontotemporal region, and in part of the striatum in the basal ganglia. Post-mortem studies show a marked reduction in the caudate nucleus of the striatum; frontotemporal gyri are narrowed, with widened intervening sulci, and the lateral ventricles are enlarged.[24]

Basophilic inclusion body disease

Another rare FTD variant, also a FTLD-FUS proteopathy, is basophilic inclusion body disease (BIBD).[26][27]

Other characteristics

In later stages of FTD, the clinical phenotypes may overlap.[21] People with FTD tend to struggle with binge eating and compulsive behaviors.[28] Binge eating habits are often associated with changes in food preferences (cravings for more sweets, carbohydrates), eating inedible objects and snatching food from others. Recent findings from structural MRI research have indicated that eating changes in FTD are associated with atrophy (wasting) in the right ventral insula, striatum, and orbitofrontal cortex.[28]

People with FTD show marked deficiencies in executive functioning and working memory.[29] Most become unable to perform skills that require complex planning or sequencing.[30] In addition to the characteristic cognitive dysfunction, a number of primitive reflexes known as frontal release signs are often able to be elicited. Usually the first of these frontal release signs to appear is the palmomental reflex which appears relatively early in the disease course whereas the palmar grasp reflex and rooting reflex appear late in the disease course.[citation needed]

In rare cases, FTD can occur in people with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a motor neuron disease. The prognosis for people with ALS is worse when combined with FTD, shortening survival by about a year.[31]

Genetics

A higher proportion of frontotemporal dementias seem to have a familial component than other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease. More and more mutations and genetic variants are being identified all the time, needing constant updating of genetic influences.

- Tau-positive frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) is caused by mutations in the MAPT gene on chromosome 17 that encodes the tau protein.[32] It has been determined that there is a direct relationship between the type of tau mutation and the neuropathology of gene mutations. The mutations at the splice junction of exon 10 of tau lead to the selective deposition of the repetitive tau in neurons and glia. The pathological phenotype associated with mutations elsewhere in tau is less predictable, with both typical neurofibrillary tangles (consisting of both 3-repeat and 4-repeat tau) and Pick bodies (consisting of 3-repeat tau) having been described. The presence of tau deposits within glia is also variable in families with mutations outside of exon 10. This disease is now informally designated FTDP-17T. FTD shows a linkage to the region of the tau locus on chromosome 17, but it is believed that there are two loci leading to FTD within megabases of each other on chromosome 17.[33] The only other known autosomal dominant genetic cause of FTLD-tau is a hypomorphic mutation in VCP which is associated with a unique neuropathology called vacuolar tauopathy.[34]

- FTD caused by FTLD-TDP43 has numerous genetic causes. Some cases are due to mutations in the GRN gene, also located on chromosome 17. Others are caused by hypomorphic VCP mutations, although these patients present with a complex picture of multisystem proteinopathy that can include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, inclusion body myopathy, Paget's disease of bone, and FTD. The most recent addition to the list (as of 2019) was a hexanucleotide repeat expansion in intron 1 of C9ORF72.[35][36][37] Only one or two cases have been reported describing TARDBP (the TDP-43 gene) mutations in a clinically-pure FTD (FTD without MND).[citation needed]

- Several other genes have been linked to this condition. These include CYLD, OPTN, SQSTM1 and TBK1.[38] These genes have been implicated in the autophagy pathway.

- No genetic causes of FUS pathology in FTD have yet been reported.[citation needed]

- Major alleles of TMEM106B SNPs have been found to be associated with risk of FTLD.[39]

Pathology

There are three main histological subtypes found at post-mortem: FTLD-tau, FTLD-TDP, and FTLD-FUS. In rare cases, patients with clinical FTD were found to have changes consistent with Alzheimer's disease on autopsy.[40] The most severe brain atrophy appears to be associated with behavioral variant FTD, and corticobasal degeneration.[41]

With regard to the genetic defects that have been found, repeat expansion in the C9orf72 gene is considered a major contribution to frontotemporal lobar degeneration, although defects in the GRN and MAPT genes are also associated with it.[42]

DNA damage and the defective repair of such damages have been etiologically linked to various neurodegenerative diseases including FTD.[43]

Diagnosis

FTD is traditionally difficult to diagnose owing to the diverse nature of the associated symptoms. Signs and symptoms are classified into three groups based on the affected functions of the frontal and temporal lobes:[15] These are behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia. An overlap between symptoms can occur as the disease progresses and spreads through the brain regions.[16] Structural MRI scans often reveal frontal lobe and/or anterior temporal lobe atrophy but in early cases the scan may seem normal. Atrophy can be either bilateral or asymmetric.[10] Registration of images at different points of time (e.g., one year apart) can show evidence of atrophy that otherwise (at individual time points) may be reported as normal. Many research groups have begun using techniques such as magnetic resonance spectroscopy, functional imaging and cortical thickness measurements in an attempt to offer an earlier diagnosis to the FTD patient. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans classically show frontal and/or anterior temporal hypometabolism, which helps differentiate the disease from Alzheimer's disease. The PET scan in Alzheimer's disease classically shows biparietal hypometabolism. Meta-analyses based on imaging methods have shown that frontotemporal dementia mainly affects a frontomedial network discussed in the context of social cognition or 'theory of mind'.[44] This is entirely in keeping with the notion that on the basis of cognitive neuropsychological evidence, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is a major locus of dysfunction early on in the course of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal degeneration.[45] The language subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (semantic dementia and progressive nonfluent aphasia) can be regionally dissociated by imaging approaches in vivo.[46]

The confusion between Alzheimer's and FTD is justifiable due to the similarities between their initial symptoms. Patients do not have difficulty with movement and other motor tasks.[47] As FTD symptoms appear, it is difficult to differentiate between a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and FTD. There are distinct differences in the behavioral and emotional symptoms of the two dementias – notably, the blunting of emotions seen in FTD patients.[10] In the early stages of FTD, anxiety and depression are common, which may result in an ambiguous diagnosis. However, over time, these ambiguities fade away as this dementia progresses and defining symptoms of apathy, unique to FTD, start to appear.[citation needed]

Recent studies over several years have developed new criteria for the diagnosis of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). The confirmatory diagnosis is made by brain biopsy, but other tests can be used to help, such as MRI, EEG, CT, and physical examination and history.[48] Six distinct clinical features have been identified as symptoms of bvFTD.[49]

- Disinhibition

- Apathy / Inertia

- Loss of Sympathy / Empathy

- Perseverative / Compulsive behaviors

- Hyperorality

- Dysexecutive neuropsychological profile

Of the six features, three must be present in a patient to diagnose one with possible bvFTD. Similar to standard FTD, the primary diagnosis stems from clinical trials that identify the associated symptoms, instead of imaging studies.[49] The above criteria are used to distinguish bvFTD from disorders such as Alzheimer's and other causes of dementia. In addition, the new criteria allow for a diagnostic hierarchy distinguished possible, probable, and definite bvFTD based on the number of symptoms present.[citation needed]

A 2021 study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, determined that using cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers of pathologic amyloid plaques, tangles, and neurodegeneration – collectively called ATN – can be useful in diagnosing FTD.[50]

Neuropsychological tests

The progression of the degeneration caused by bvFTD may follow a predictable course. The degeneration begins in the orbitofrontal cortex and medial aspects such as ventromedial cortex. In later stages, it gradually expands its area to the dorsolateral cortex and the temporal lobe.[51] Thus, the detection of dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex and ventromedial cortex is important in the detection of early stage bvFTD. As stated above, a behavioural change may occur before the appearance of any atrophy in the brain in the course of the disease. Because of that, image scanning such as MRI can be insensitive to the early degeneration and it is difficult to detect early-stage bvFTD.[citation needed]

In neuropsychology, there is an increasing interest in using neuropsychological tests such as the Iowa gambling task or Faux Pas Recognition test as an alternative to imaging for the diagnosis of bvFTD.[52] Both the Iowa gambling task and the Faux Pas test are known to be sensitive to dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex.[citation needed]

Faux Pas Recognition test is intended to measure one's ability to detect faux pas types of social blunders (accidentally make a statement or an action that offends others). It is suggested that people with orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction show a tendency to make social blunders due to a deficit in self-monitoring.[53] Self-monitoring is the ability of individuals to evaluate their behaviour to make sure that their behaviour is appropriate in particular situations. The impairment in self-monitoring leads to a lack of social emotion signals. The social emotions such as embarrassment are important in the way that they signal the individual to adapt social behaviour in an appropriate manner to maintain relationships with others. Though patients with damage to the OFC retain intact knowledge of social norms, they fail to apply it to actual behaviour because they fail to generate social emotions that promote adaptive social behaviour.[53]

The other test, the Iowa gambling task, is a psychological test intended to simulate real-life decision making. The underlying concept of this test is the somatic marker hypothesis. This hypothesis argues that when people have to make complex uncertain decisions, they employ both cognitive and emotional processes to assess the values of the choices available to them. Each time a person makes a decision, both physiological signals and evoked emotion (somatic marker) are associated with their outcomes and it accumulates as experience. People tend to choose the choice which might produce the outcome reinforced with positive stimuli, thus it biases decision-making towards certain behaviours while avoiding others.[54] It is thought that somatic markers are processed in orbitofrontal cortex.[citation needed]

The symptoms observed in bvFTD are caused by dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex, thus these two neuropsychological tests might be useful in detecting early-stage bvFTD. However, as self-monitoring and somatic marker processes are so complex, it likely involves other brain regions. Therefore, neuropsychological tests are sensitive to the dysfunction of orbitofrontal cortex, yet not specific to it. The weakness of these tests is that they do not necessarily show dysfunction of the orbitofrontal cortex.[citation needed]

In order to solve this problem, some researchers combined neuropsychological tests which detect the dysfunction of orbitofrontal cortex into one, so that it increases its specificity to the degeneration of the frontal lobe, in order to detect the early-stage bvFTD. They invented the Executive and Social Cognition Battery which comprises five neuropsychological tests:[52]

- Faux Pas test

- Hotel task

- Iowa gambling task

- Mind in the Eyes

- Multiple Errands task

The result has shown that this combined test is more sensitive in detecting the deficits in early bvFTD.[52]

Management

Currently, there is no cure for FTD. Treatments are available to manage the behavioral symptoms. Disinhibition and compulsive behaviors can be controlled by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).[55][56] Although Alzheimer's and FTD share certain symptoms, they cannot be treated with the same pharmacological agents because the cholinergic systems are not affected in FTD.[10]

Because FTD often occurs in relatively younger adults (i.e. in their 40s or 50s), it can severely affect families. Patients often still have children living in the home.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Symptoms of frontotemporal dementia progress at a rapid, steady rate. Patients with the disease can survive for 2–20 years. Eventually patients will need 24-hour care for daily function.[57]

Cerebrospinal fluid leaks are a known cause of reversible frontotemporal dementia.[58]

History

Features of FTD were first described by the Czech psychiatrist Arnold Pick between 1892 and 1906.[12][59] The name Pick's disease was coined in 1922.[13] This term is now reserved only for behavioral variant FTD which shows the presence of the characteristic Pick bodies and Pick cells,[14][15] which were first described by Alois Alzheimer in 1911.[13]

In 1989, Snowden suggested the term "semantic dementia" to describe the patient with predominant left temporal atrophy and aphasia that Pick described. The first research criteria for FTD, "Clinical and neuropathological criteria for frontotemporal dementia. The Lund and Manchester Groups", was developed in 1994. The clinical diagnostic criteria were revised in the late 1990s, when the FTD spectrum was divided into a behavioral variant, a nonfluent aphasia variant and a semantic dementia variant.[19] The most recent revision of the clinical research criteria was by International Behavioural Variant FTD Criteria Consortium (FTDC) in 2011.[49]

Notable cases

People who have been diagnosed as having FTD (often referred to as Pick's disease in cases of the behavioral variant) include:

- John Berry (1963–2016), American hardcore punk musician and founding member of the Beastie Boys[60]

- Clancy Blair (born 1960), American developmental psychologist and professor[citation needed]

- Don Cardwell (1935–2008), Major League Baseball pitcher[61]

- Charmian Carr (1942–2016), who played Liesl, from the Sound of Music, born Charmian Anne Farnon

- Jerry Corbetta (1947–2016), frontman, organist and keyboardist of American psychedelic rock band Sugarloaf[62]

- Ted Darling (1935–1996), Buffalo Sabres television announcer

- Robert W. Floyd (1936–2001), computer scientist[63]

- Colleen Howe (1933–2009), sports agent and hockey team manager, known as "Mrs. Hockey"[64]

- Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899–1976) national poet of Bangladesh[65]

- Terry Jones (1942-2020), Welsh comedian (Monty Python) and director

- Ralph Klein (1942–2013), former premier of Alberta, Canada

- Kevin Moore (1958–2013), English footballer[66]

- Ernie Moss (1949–2021), English footballer[67]

- Nic Potter (1951–2013), British bassist for Van der Graaf Generator[68]

- Christina Ramberg (1946–1995), American painter associated with the Chicago Imagists[69]

- David Rumelhart (1942–2011), American cognitive psychologist[citation needed]

- Sir Nicholas Wall (1945–2017), English judge[70]

- Bruce Willis (born 1955), American actor [71]

- Mark Wirtz (1943–2020), pop musician, composer and producer[72]

See also

- Alcoholic dementia

- Lewy body dementia

- Logopenic progressive aphasia

- Mini-SEA

- Proteopathy

- Transportin 1

- Vascular dementia

References

- ↑ Perez, L., "Ron Oberman, Senior Record Executive and Former Publicist to David Bowie, Dies at 76", The Hollywood Reporter, November 24, 2019.

- ↑ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. pp. 614–618. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ↑ "ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f831337417.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Sivasathiaseelan, Harri; Marshall, Charles; Agustus, Jennifer; Benhamou, Elia; Bond, Rebecca; van Leeuwen, Janneke; Hardy, Chris; Rohrer, Jonathan et al. (April 2019). "Frontotemporal Dementia: A Clinical Review". Seminars in Neurology 39 (2): 251–263. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1683379. PMID 30925617. https://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/xmlui/handle/123456789/57968.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "RNA Binding Proteins and the Pathogenesis of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration". Annual Review of Pathology 14: 469–495. 24 January 2019. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012955. PMID 30355151.

- ↑ "Brain Cells for Socializing". Smithsonian. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/brain-cells-for-socializing-133855450/?no-ist=&onsite_medium=internallink&page=3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "What are the Different Types of Frontotemporal Disorders?" (in en). https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/types-frontotemporal-disorders.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "What is frontotemporal dementia". https://www.dementiauk.org/understanding-dementia/types-and-symptoms/frontotemporal-dementia/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Finger, EC (April 2016). "Frontotemporal Dementias.". Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.) 22 (2 Dementia): 464–89. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000300. PMID 27042904.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 "Frontotemporal dementia". Br J Psychiatry 180 (2): 140–3. February 2002. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.2.140. PMID 11823324.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "FRONTotemporal dementia Incidence European Research Study-FRONTIERS: Rationale and design". Alzheimers Dement 18 (3): 498–506. March 2022. doi:10.1002/alz.12414. PMID 34338439.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "History of Pick's disease" (in en). Revue Neurologique 174 (10): 740–741. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2018.09.009. ISSN 0035-3787. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0035378718308245#bib0130.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "Pick's disease". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 74 (2): 169. 2003. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.2.169. PMID 12531941.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology (eleventh ed.). McGraw Hill. 2019. p. 1096.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Frontotemporal dementia: a review for primary care physicians". Am Fam Physician 82 (11): 1372–7. December 2010. PMID 21121521. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2010/1201/p1372.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management". CNS Drugs 24 (5): 375–98. May 2010. doi:10.2165/11533100-000000000-00000. PMID 20369906.

- ↑ "Focus on Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD) | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Current-Research/Focus-Disorders/Alzheimers-Related-Dementias/Focus-Frontotemporal-Dementia-FTD.

- ↑ Drs; Sartorius, Norman; Henderson, A.S.; Strotzka, H.; Lipowski, Z.; Yu-cun, Shen; You-xin, Xu; Strömgren, E.; Glatzel, J. et al.. "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines". Microsoft Word. p. 51. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/classification/other-classifications/9241544228_eng.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Olney, Nicholas T.; Spina, Salvatore; Miller, Bruce L. (May 2017). "Frontotemporal Dementia". Neurologic Clinics 35 (2): 339–374. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2017.01.008. PMID 28410663.

- ↑ "Frontotemporal Dementia Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Frontotemporal-Dementia-Information-Page.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 "Molecular Pathways of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration". Annual Review of Neuroscience 33 (1): 71–88. 2010. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153144. PMID 20415586.

- ↑ Bang, J.; Spina, S.; Miller, B. L. (24 October 2015). "Frontotemporal dementia.". Lancet 386 (10004): 1672–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4. PMID 26595641.

- ↑ Gaillard, Frank. "Pick bodies | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". https://radiopaedia.org/articles/pick-bodies?lang=gb.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Cairns, N. J.; Grossman, M.; Arnold, S. E.; Burn, D. J.; Jaros, E.; Perry, R. H.; Duyckaerts, C.; Stankoff, B. et al. (26 October 2004). "Clinical and neuropathologic variation in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease". Neurology 63 (8): 1376–1384. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000139809.16817.dd. PMID 15505152.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Armstrong, Richard A.; Gearing, Marla; Bigio, Eileen H.; Cruz-Sanchez, Felix F.; Duyckaerts, Charles; Mackenzie, Ian R. A.; Perry, Robert H.; Skullerud, Kari et al. (November 2011). "Spatial patterns of FUS-immunoreactive neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCI) in neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease (NIFID)". Journal of Neural Transmission 118 (11): 1651–1657. doi:10.1007/s00702-011-0690-x. PMID 21792670.

- ↑ Ito, H (December 2014). "Basophilic inclusions and neuronal intermediate filament inclusions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration". Neuropathology 34 (6): 589–95. doi:10.1111/neup.12119. PMID 24673472.

- ↑ Munoz, D. G. (November 2009). "FUS pathology in basophilic inclusion body disease". Neuropathology 118 (5): 617–27. doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0598-9. PMID 19830439.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Piguet O (November 2011). "Eating disturbance in behavioural-variant frontotemporal dementia". J. Mol. Neurosci. 45 (3): 589–93. doi:10.1007/s12031-011-9547-x. PMID 21584651.

- ↑ Neary, David; Snowden, Julie; Mann, David (November 2005). "Frontotemporal dementia". The Lancet Neurology 4 (11): 771–780. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70223-4. PMID 16239184.

- ↑ Kramer, Joel H.; Jurik, Jennifer; Sha, Sharon J.; Rankin, Kate P.; Rosen, Howard J.; Johnson, Julene K.; Miller, Bruce L. (December 2003). "Distinctive Neuropsychological Patterns in Frontotemporal Dementia, Semantic Dementia, And Alzheimer Disease". Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology 16 (4): 211–218. doi:10.1097/00146965-200312000-00002. PMID 14665820.

- ↑ Olney, R. K.; Murphy, J.; Forshew, D.; Garwood, E.; Miller, B. L.; Langmore, S.; Kohn, M. A.; Lomen-Hoerth, C. (13 December 2005). "The effects of executive and behavioral dysfunction on the course of ALS". Neurology 65 (11): 1774–1777. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000188759.87240.8b. PMID 16344521.

- ↑ Buée, Luc; Delacourte, André (October 1999). "Comparative Biochemistry of Tau in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, Corticobasal Degeneration, FTDP-17 and Pick's Disease". Brain Pathology 9 (4): 681–693. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00550.x. PMID 10517507.

- ↑ Hardy, John; Momeni, Parastoo; Traynor, Bryan J. (1 April 2006). "Frontal temporal dementia: dissecting the aetiology and pathogenesis". Brain 129 (4): 830–831. doi:10.1093/brain/awl035. PMID 16543401.

- ↑ Darwich, Nabil F.; Phan, Jessica M.; Kim, Boram; Suh, EunRan; Papatriantafyllou, John D.; Changolkar, Lakshmi; Nguyen, Aivi T.; O'Rourke, Caroline M. et al. (20 November 2020). "Autosomal dominant VCP hypomorph mutation impairs disaggregation of PHF-tau". Science 370 (6519): eaay8826. doi:10.1126/science.aay8826. PMID 33004675.

- ↑ Convery, R.; Mead, S.; Rohrer, J. D. (February 2019). "Review: Clinical, genetic and neuroimaging features of frontotemporal dementia". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 45 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1111/nan.12535. PMID 30582889. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10068269/1/Convery_FTD_review_versrev1-3.pdf.

- ↑ "How do C9ORF72 repeat expansions cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: can we learn from other noncoding repeat expansion disorders?". Current Opinion in Neurology 25 (6): 689–700. December 2012. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835a3efb. PMID 23160421.

- ↑ "DNA repair and neurological disease: From molecular understanding to the development of diagnostics and model organisms". DNA Repair 81: 102669. September 2019. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102669. PMID 31331820.

- ↑ Dobson-Stone, Carol; Hallupp, Marianne; Shahheydari, Hamideh; Ragagnin, Audrey M G; Chatterton, Zac; Carew-Jones, Francine; Shepherd, Claire E; Stefen, Holly et al. (1 March 2020). "CYLD is a causative gene for frontotemporal dementia – amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Brain 143 (3): 783–799. doi:10.1093/brain/awaa039. PMID 32185393.

- ↑ Feng, Tuancheng; Lacrampe, Alexander; Hu, Fenghua (March 2021). "Physiological and pathological functions of TMEM106B: a gene associated with brain aging and multiple brain disorders". Acta Neuropathologica 141 (3): 327–339. doi:10.1007/s00401-020-02246-3. ISSN 1432-0533. PMID 33386471.

- ↑ "Clinical and psychometric distinction of frontotemporal and Alzheimer dementias". Arch. Neurol. 64 (4): 535–40. April 2007. doi:10.1001/archneur.64.4.535. PMID 17420315.

- ↑ Rohrer, J. D.; Lashley, T.; Schott, J. M.; Warren, J. E.; Mead, S.; Isaacs, A. M.; Beck, J.; Hardy, J. et al. (1 September 2011). "Clinical and neuroanatomical signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration". Brain 134 (9): 2565–2581. doi:10.1093/brain/awr198. PMID 21908872.

- ↑ van der Zee, Julie; Van Broeckhoven, Christine (February 2014). "Frontotemporal lobar degeneration—building on breakthroughs". Nature Reviews Neurology 10 (2): 70–72. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2013.270. PMID 24394289.

- ↑ Wang H, Kodavati M, Britz GW, Hegde ML. DNA Damage and Repair Deficiency in ALS/FTD-Associated Neurodegeneration: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implication. Front Mol Neurosci. 2021 Dec 16;14:784361. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.784361. PMID 34975400; PMCID: PMC8716463

- ↑ "Neural networks in frontotemporal dementia – A meta-analysis". Neurobiology of Aging 29 (3): 418–426. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.10.023. PMID 17140704.

- ↑ Rahman, Shibley; Sahakian, Barbara J.; Hodges, John R.; Rogers, Robert D.; Robbins, Trevor W. (August 1999). "Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia". Brain 122 (8): 1469–1493. doi:10.1093/brain/122.8.1469. PMID 10430832.

- ↑ "Towards a nosology for frontotemporal lobar degenerations – A meta-analysis involving 267 subjects". NeuroImage 36 (3): 497–510. 2007. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.024. PMID 17478101.

- ↑ "Impact of DNA testing for early-onset familial Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal dementia". Arch. Neurol. 58 (11): 1828–31. November 2001. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.11.1828. PMID 11708991.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Frontotemporal dementia

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Rascovsky, Katya; Hodges, John R.; Knopman, David; Mendez, Mario F.; Kramer, Joel H.; Neuhaus, John; van Swieten, John C.; Seelaar, Harro et al. (September 2011). "Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia". Brain 134 (9): 2456–2477. doi:10.1093/brain/awr179. PMID 21810890.

- ↑ Cousins, Katheryn A. Q.; Phillips, Jeffrey S.; Irwin, David J.; Lee, Edward B.; Wolk, David A.; Shaw, Leslie M.; Zetterberg, Henrik; Blennow, Kaj et al. (May 2021). "ATN incorporating cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light chain detects frontotemporal lobar degeneration". Alzheimer's & Dementia 17 (5): 822–830. doi:10.1002/alz.12233. ISSN 1552-5279. PMID 33226735.

- ↑ Krueger, C.E.; Bird, A.C.; Growdon, M.E.; Jang, J.Y.; Miller, B.L.; Kramer, J.K. (2009). "Conflict in monitoring early frontotemporal dementia". Neurology 73 (5): 349–55. doi:10.1212/wnl.0b013e3181b04b24. PMID 19652138.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Torralva, T; Roca, M; Gleichgerrcht, E; Bekinschtein, T; Manes, F (2009). "A neuropsychological battery to detect specific executive and social cognitive impairments in early frontotemporal dementia". Brain 132 (5): 1299–1309. doi:10.1093/brain/awp041. PMID 19336463. https://academic.oup.com/brain/article-pdf/132/5/1299/17862773/awp041.pdf.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Beer, J.S.; John, O.P.; Scabini, D.; Knight, R.T. (2006). "Orbitofrontal cortex and Social behaviour: Integrating Self-monitoring and Emotion-cognition interactions". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 18 (6): 871–888. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.871. PMID 16839295.

- ↑ Damasio, A.R.; Everitt, B. J.; Bishop, D. (29 October 1996). "The Somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 351 (1346): 1413–20. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0125. PMID 8941953.

- ↑ "Frontotemporal dementia: treatment response to serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors". J Clin Psychiatry 58 (5): 212–6. May 1997. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0506. PMID 9184615.

- ↑ "Medications for behavioral symptoms". ucsf.edu. http://memory.ucsf.edu/ftd/overview/ftd/treatment/multiple/behavioral.

- ↑ Kertesz A (June 2004). "Frontotemporal dementia/Pick's disease". Arch. Neurol. 61 (6): 969–71. doi:10.1001/archneur.61.6.969. PMID 15210543.

- ↑ Samson, K. (2002). "Hypotension May Cause Frontotemporal Dementia". Neurology Today 2 (9): 35–36. doi:10.1097/00132985-200209000-00013.

- ↑ PICK, A. (1892). "Uber die Beziehungen der senilen Hirnatrophie zur Aphasie". Prag Med Wochenschr 17: 165–167. https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10021235320/amp/ja.

- ↑ Oyebode, Jan (31 May 2016). "Beastie Boy John Berry Died of Frontal Lobe Dementia – But What Is It?". https://scitechconnect.elsevier.com/beastie-boy-died-frontal-lobe-dementia/.

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard. Don Cardwell, 72, Pitcher for 1969 Mets, Is Dead. The New York Times . January 16, 2008

- ↑ "Sugarloaf frontman Jerry Corbetta dead at 68 – The Denver Post". 2016-09-20. http://www.denverpost.com/2016/09/20/colorado-hitmaker-jerry-corbetta-dead-at-68/.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald E. (December 2003). "Robert W Floyd, In Memoriam". ACM SIGACT News 34 (4): 3–13. doi:10.1145/954092.954488. http://www-cs-faculty.stanford.edu/~uno/papers/floyd.ps.gz.

- ↑ Sipple, George (March 6, 2009). "Fans mourn loss of "Mrs. Hockey," Colleen Howe". http://www.freep.com/article/20090306/SPORTS05/90306069?imw=Y.

- ↑ Farooq, Mohammad Omar. "Kazi Nazrul Islam: Illness and Treatment". http://www.nazrul.org/nazrul_life/illness.htm.

- ↑ Sportsteam. "Grimsby Town legend Kevin Moore passes away". http://www.thisisgrimsby.co.uk/Grimsby-Town-legend-Kevin-Moore-passes-away/story-18838049-detail/story.html#axzz2RsGaeCI7.

- ↑ "Support for Valiants hero Ernie Moss after he is diagnosed with Pick's Disease". The Sentinel. 11 October 2014. http://www.stokesentinel.co.uk/Port-Vale-Support-Valiants-hero-Ernie-Moss/story-23091273-detail/story.html.

- ↑ Sally Potter (22 January 2013). "Nic Potter obituary | Music | guardian.co.uk". London: Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/jan/22/nic-potter.

- ↑ "The Sexy, Proto-Feminist Art Of Christina Ramberg's Tragically Short Life". https://www.wbur.org/artery/2014/02/27/the-sexy-proto-feminist-art-of-christina-rambergs-tragically-short-life.

- ↑ Gordon Rayner, "Sir Nicholas Wall, once Britain's top family law judge, commits suicide after dementia diagnosis", The Daily Telegraph, 23 February 2017.

- ↑ Moreau, Jordan (2023-02-16). "Bruce Willis Diagnosed With Dementia After Retiring Due to Aphasia". https://variety.com/2023/film/news/bruce-willis-dementia-aphasia-retire-1235525599/.

- ↑ obituary, The Daily Telegraph, 13 Aug 2020

Further reading

- Liu, W; Miller, B. L.; Kramer, J. H.; Rankin, K.; Wyss-Coray, C.; Gearhart, R.; Phengrasamy, L.; Weiner, M. et al. (1 March 2004). "Behavioral disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia". Neurology. 5 62 (5): 742–748. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000113729.77161.C9. PMID 15007124.

- Hodges, J.R (2 April 2003). "A study of stereotypic behaviours in Alzheimer's disease and frontal and temporal variant frontotemporal dementia". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 74 (10): 1398–1402. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.10.1398. PMID 14570833.

- "GRN Frontotemporal Dementia". GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington. 1993. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1371/.

- "MAPT-Related Frontotemporal Dementia". GeneReviews. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle. 1993. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1505/.

- Marilyn Reynolds. "'Til Death or Dementia Do us Part, a memoir". River Rock Books. https://www.riverrockbooks.com/prints/til-death-or-dementia-do-us-part-a-memoir-by-marilyn-reynolds.

- Upson, Sandra (15 April 2020). "The Devastating Decline of a Brilliant Young Coder". Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/lee-holloway-devastating-decline-brilliant-young-coder/. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

de:Frontotemporale Demenz

|