Biology:Cutinase

The enzyme cutinase (systematic name: cutin hydrolase, EC 3.1.1.74) is a member of the hydrolase family. It catalyzes the following reaction:

| Cutinase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Cutinase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01083 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000675 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00140 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1cex / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| OPM superfamily | 127 | ||||||||

| OPM protein | 1oxm | ||||||||

| |||||||||

[math]\ce{ R1COOR2 + H2O -> R1COOH + R2OH }[/math]

In biological systems, the reactant carboxylic ester is a constituent of the cutin polymer, and the hydrolysis of cutin results in the formation of alcohol and carboxylic acid monomer products.

Nomenclature

Cutinase has an assigned enzyme commission number of EC 3.1.1.74.[2] Cutinase is in the third class of enzymes, meaning that its primary function is to hydrolyze its substrate (in this case, cutin).[3] Within the third class, cutinase is further categorized into the first subclass, which indicates that it specifically hydrolyzes ester bonds.[2] It is then placed in the first sub-subclass, meaning that it targets carboxylic esters, which are those that join together cutin polymers.[2]

Function

Most plants have a layer composed of cutin, called the cuticle, on their aboveground surfaces such as stems, leaves, and fruits.[4] This layer of cutin is formed by a matrix-like structure that contains waxy components embedded in the carbohydrate layers.[5] The molecule, cutin, which composes most of the cuticle matrix (40-80%), is composed primarily of fatty acid chains that are polymerized via carboxylic ester bonds.[4][6]

Research suggests that cutin plays a critical role in preventing pathogenic infections in plant systems.[7] For instance, experiments conducted on tomato plants that had a substantial inability to synthesize cutin found that that tomatoes produced by those plants were significantly more susceptible to infection by both opportunistic pathogens and intentionally inoculated fungal spores.[8]

Cutinase is produced by a variety of fungal plant pathogens, and its activity was first detected in the fungus, Penicillium spinulosum.[9] In studies of Nectria haematococca, a fungal pathogen that is the cause of foot rot in pea plants, cutinase has been shown to play key roles in facilitating the early stages of plant infection.[9] It is also suggested that fungal spores that make initial contact with plant surfaces, a small amount of catalytic cutinase produces cutin monomers which in turn up-regulate the expression of the cutinase gene.[9] This proposes that the expression pathway of cutinase in fungal spores is characterized by a positive feedback loop until the fungus successfully breaches the cutin layer; however, the specific mechanism of this pathway is unclear.[9][10] Inhibition of cutinase has been shown to prevent fungal infection through intact cuticles.[10] Conversely, the supplementation of cutinase to fungi that are not able to produce it naturally had been shown to enhance fungal infection success rates.[9]

Cutinases have also been observed in a few plant pathogenic bacterial species, such as Streptomyces scabies, Thermobifida fusca, Pseudomonas mendocina, and Pseudomonas putida, but these have not been studied to the extent as those found in fungi.[11][12] The molecular structure of the Thermobifida fusca cutinase shows similarities to the Fusarium solani pisi fungal cutinase, with congruencies in their active sites and overall mechanisms.[11]

Structure

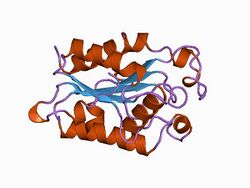

Cutinase belongs to the α-β class of proteins, with a central β-sheet of 5 parallel strands covered by 5 alpha helices on either side of the sheet.[13] Fungal cutinase is generally composed of around 197 amino acid residues, and its native form consists of a single domain.[14] The protein also contains 4 invariant cysteine residues that form 2 disulfide bridges, whose cleavage results in a complete loss of enzymatic activity.[15][14]

Crystal structures have shown that the active site of cutinases is found on one end of the ellipsoid shape of the enzyme.[16] This active site is seen flanked by two hydrophobic loop structures and partly covered by 2 thin bridges formed by amino acid side chains.[13][16] It does not possess a hydrophobic lid, which is a common constituent feature among other lipases.[13] Instead, the catalytic serine in the active site is exposed to open solvent, and the cutinase enzyme does not show interfacial activation behaviors at an aqueous-nonpolar interface.[13][14] Cutinase activation is believed to be derived from slight shifts in the conformation of hydrophobic residues, acting as a miniature lid.[13] The oxyanion hole in the active site is a constituent feature of the binding site, which differs from most lipolytic enzymes whose oxyanion holes are induced upon substrate binding.[17]

Mechanism

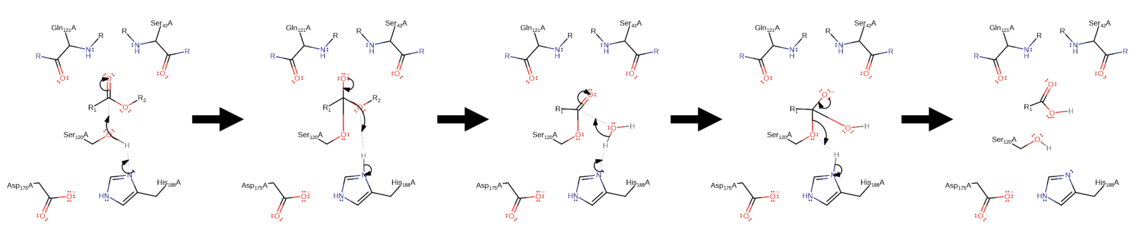

Cutinase is a serine esterase, and the active site contains a serine-histidine-aspartate triad and an oxyanion hole, which are signature elements of serine hydrolases.[15][18] The binding site of the cutin lipid polymer consists of two hydrophobic loops characterized by nonpolar amino acids such as leucine, alanine, isoleucine, and proline.[18] These hydrophobic residues show a higher degree of flexibility, suggesting an induced fit model to facilitate cutin bonding to the active site.[13] In the cutinase active site, histidine deprotonates serine, allowing the serine to undergo a nucleophilic attack on the cutin carboxylic ester.[19] This is followed by an elimination reaction whereby the charged oxygen (stabilized by the oxyanion hole) creates a double bond, removing an R group from the cutin polymer in the form of an alcohol.[19] The process repeats with a nucleophilic attack on the new carboxylic ester by a deprotonated water molecule.[19] Following this, the charged oxygen reforms its double bond, removing the serine attachment and releasing the carboxylic acid R monomer.[19]

Applications

The stability of cutinases in higher temperatures (20-50 °C) and its compatibility with other hydrolytic enzymes has potential applications in the detergent industry.[20] In fact, it has been shown that cutinases are more efficient at cleaving and eliminating non-calcium fats from clothing when compared against other industrial lipases.[21] Another advantage of cutinase in this industry is its ability to be catalytically active with both water- and lipid-soluble ester compounds, making it a more versatile degradative agent.[20] This versatility is also subjecting cutinase to experiments in enhancing the biofuel industry because of its ability to facilitate transesterification of biofuels in various solubility environments.[20]

Rather unexpectedly, the ability to degrade the cutin layer of plants and their fruits holds the potential to be beneficial to the fruit industry.[20] This is because the cuticle layer of fruits is a putative mechanism of water regulation, and the degradation of this layer subjects the fruits to water movement across its membrane.[22] By using cutinase to degrade the cuticle of fruits, industry makers can enhance the drying of fruits and more easily deliver preservatives and additives to the flesh of the fruit.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ "Atomic resolution (1.0 A) crystal structure of Fusarium solani cutinase: stereochemical analysis". Journal of Molecular Biology 268 (4): 779–799. May 1997. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1000. PMID 9175860.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "EC 3.1.1.74: Cutinase". IUBMB Nomenclature Home Page. 2018-10-10. http://www.sbcs.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/EC3/1/1/74.html.

- ↑ "Enzyme nomenclature and classification: the state of the art". The FEBS Journal 290 (9): 2214–2231. November 2021. doi:10.1111/febs.16274. PMID 34773359.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Biophysical and biochemical characteristics of cutin, a plant barrier biopolymer". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1620 (1–3): 1–7. March 2003. doi:10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00510-x. PMID 12595066.

- ↑ "Waxes, cutin and suberin". Methods Plant Biochemisry 4: 105–158. 1990. https://www.academia.edu/24494725.

- ↑ Plant cuticles : an integrated functional approach. BIOS Scientific Publishers. 1996. ISBN 1-85996-130-4. OCLC 36076660. http://worldcat.org/oclc/36076660.

- ↑ "The Plant Polyester Cutin: Biosynthesis, Structure, and Biological Roles". Annual Review of Plant Biology 67 (1): 207–233. April 2016. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111929. PMID 26865339.

- ↑ "Cutin deficiency in the tomato fruit cuticle consistently affects resistance to microbial infection and biomechanical properties, but not transpirational water loss". The Plant Journal 60 (2): 363–377. October 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03969.x. PMID 19594708.; Lay summary in: "Faculty Opinions". doi:10.3410/f.1164954.625804. https://facultyopinions.com/article/1164954#related-articles.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "The role of cutinase in fungal pathogenicity". Trends in Microbiology 1 (2): 69–71. May 1993. doi:10.1016/0966-842x(93)90037-r. ISSN 0966-842X. PMID 8044466.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Cloning and analysis of CUT1, a cutinase gene from Magnaporthe grisea". Molecular & General Genetics 232 (2): 174–182. March 1992. doi:10.1007/bf00279994. PMID 1557023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Identification and characterization of bacterial cutinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 (38): 25854–25862. September 2008. doi:10.1074/jbc.m800848200. PMID 18658138.

- ↑ "Production of cutinase byThermomonospora fuscaATCC 27730". Journal of Applied Microbiology 86 (4): 561–568. April 1999. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00690.x. ISSN 1364-5072.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 "Fusarium solani cutinase is a lipolytic enzyme with a catalytic serine accessible to solvent". Nature 356 (6370): 615–618. April 1992. doi:10.1038/356615a0. PMID 1560844. Bibcode: 1992Natur.356..615M.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Cutinase structure, function and biocatalytic applications". Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 1 (2): 160–173. 1998-12-15. doi:10.2225/vol1-issue3-fulltext-8. ISSN 0717-3458. http://www.bioline.org.br/abstract?id=ej98020.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Structure of cutinase gene, cDNA, and the derived amino acid sequence from phytopathogenic fungi". Biochemistry 26 (24): 7883–7892. 1987-12-01. doi:10.1021/bi00398a052. ISSN 0006-2960.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Packing forces in nine crystal forms of cutinase". Proteins 31 (3): 320–333. May 1998. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980515)31:3<320::aid-prot8>3.0.co;2-m. PMID 9593202.

- ↑ "Contribution of cutinase serine 42 side chain to the stabilization of the oxyanion transition state". Biochemistry 35 (2): 398–410. January 1996. doi:10.1021/bi9515578. PMID 8555209.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Cutinase, a lipolytic enzyme with a preformed oxyanion hole". Biochemistry 33 (1): 83–89. January 1994. doi:10.1021/bi00167a011. PMID 8286366.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Cutinase" (in en). https://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/m-csa/entry/631/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 "Production, characterization and applications of microbial cutinases". Process Biochemistry 44 (2): 127–134. February 2009. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2008.09.008. ISSN 1359-5113.

- ↑ "[6] Impact of structural information on understanding lipolytic function". Impact of structural information on understanding lipolytic function. Methods in Enzymology. 284. Elsevier. 1997. pp. 119–129. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(97)84008-6. ISBN 9780121821852.

- ↑ "5510131 Enzyme assisted degradation of surface membranes of harvested fruits and vegetables". Biotechnology Advances 15 (1): 273. January 1997. doi:10.1016/s0734-9750(97)88551-5. ISSN 0734-9750.

Further reading

- Sulaiman, S.; Yamato, S.; Kanaya, E.; Kim, J. J.; Koga, Y.; Takano, K.; Kanaya, S. (2012). "Isolation of a Novel Cutinase Homolog with Polyethylene Terephthalate-Degrading Activity from Leaf-Branch Compost by Using a Metagenomic Approach". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 78 (5): 1556–1562. doi:10.1128/AEM.06725-11. PMID 22194294. Bibcode: 2012ApEnM..78.1556S.

- Shirke, Abhijit N.; White, Christine; Englaender, Jacob A.; Zwarycz, Allison; Butterfoss, Glenn L.; Linhardt, Robert J.; Gross, Richard A. (2018). "Stabilizing Leaf and Branch Compost Cutinase (LCC) with Glycosylation: Mechanism and Effect on PET Hydrolysis". Biochemistry 57 (7): 1190–1200. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01189. PMID 29328676.

|