Astronomy:Bekenstein bound

In physics, the Bekenstein bound (named after Jacob Bekenstein) is an upper limit on the thermodynamic entropy S, or Shannon entropy H, that can be contained within a given finite region of space which has a finite amount of energy—or conversely, the maximal amount of information required to perfectly describe a given physical system down to the quantum level.[1] It implies that the information of a physical system, or the information necessary to perfectly describe that system, must be finite if the region of space and the energy are finite. In computer science this implies that non-finite models such as Turing machines are not realizable as finite devices.

Equations

The universal form of the bound was originally found by Jacob Bekenstein in 1981 as the inequality[1][2][3] where S is the entropy, k is the Boltzmann constant, R is the radius of a sphere that can enclose the given system, E is the total mass–energy including any rest masses, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, and c is the speed of light. Note that while gravity plays a significant role in its enforcement, the expression for the bound does not contain the gravitational constant G, and so, it ought to apply to quantum field theory in curved spacetime.

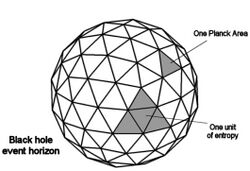

The Bekenstein–Hawking boundary entropy of three-dimensional black holes exactly saturates the bound. The Schwarzschild radius is given by and so the two-dimensional area of the black hole's event horizon is and using the Planck length the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy is

One interpretation of the bound makes use of the microcanonical formula for entropy, where is the number of energy eigenstates accessible to the system. This is equivalent to saying that the dimension of the Hilbert space describing the system is[4][5]

The bound is closely associated with black hole thermodynamics, the holographic principle and the covariant entropy bound of quantum gravity, and can be derived from a conjectured strong form of the latter.[4]

Origins

Bekenstein derived the bound from heuristic arguments involving black holes. If a system exists that violates the bound, i.e., by having too much entropy, Bekenstein argued that it would be possible to violate the second law of thermodynamics by lowering it into a black hole. In 1995, Ted Jacobson demonstrated that the Einstein field equations (i.e., general relativity) can be derived by assuming that the Bekenstein bound and the laws of thermodynamics are true.[6][7] However, while a number of arguments were devised which show that some form of the bound must exist in order for the laws of thermodynamics and general relativity to be mutually consistent, the precise formulation of the bound was a matter of debate until Casini's work in 2008.[2][3] [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

The following is a heuristic derivation that shows for some constant . Showing that requires a more technical analysis.

Suppose we have a black hole of mass , then the Schwarzschild radius of the black hole is , and the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy of the black hole is .

Now take a box of energy , entropy , and side length . If we throw the box into the black hole, the mass of the black hole goes up to , and the entropy goes up by . Since entropy does not decrease, .

In order for the box to fit inside the black hole, . If the sizes are comparable, then .

Proof in quantum field theory

A proof of the Bekenstein bound in the framework of quantum field theory was given in 2008 by Casini.[17] One of the crucial insights of the proof was to find a proper interpretation of the quantities appearing on both sides of the bound.

Naive definitions of entropy and energy density in Quantum Field Theory suffer from ultraviolet divergences. In the case of the Bekenstein bound, ultraviolet divergences can be avoided by taking differences between quantities computed in an excited state and the same quantities computed in the vacuum state. For example, given a spatial region , Casini defines the entropy on the left-hand side of the Bekenstein bound as where is the Von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix associated with in the excited state , and is the corresponding Von Neumann entropy for the vacuum state .

On the right-hand side of the Bekenstein bound, a difficult point is to give a rigorous interpretation of the quantity , where is a characteristic length scale of the system and is a characteristic energy. This product has the same units as the generator of a Lorentz boost, and the natural analog of a boost in this situation is the modular Hamiltonian of the vacuum state . Casini defines the right-hand side of the Bekenstein bound as the difference between the expectation value of the modular Hamiltonian in the excited state and the vacuum state,

With these definitions, the bound reads which can be rearranged to give

This is simply the statement of positivity of quantum relative entropy, which proves the Bekenstein bound.

However, the modular Hamiltonian can only be interpreted as a weighted form of energy for conformal field theories, and when V is a sphere.

This construction allows us to make sense of the Casimir effect[4] where the localized energy density is lower than that of the vacuum, i.e. a negative localized energy. The localized entropy of the vacuum is nonzero, and so, the Casimir effect is possible for states with a lower localized entropy than that of the vacuum. Hawking radiation can be explained by dumping localized negative energy into a black hole.

See also

- Margolus–Levitin theorem

- Landauer's principle

- Bremermann's limit

- Kolmogorov complexity

- Beyond black holes

- Digital physics

- Limits of computation

- Chandrasekhar limit

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bekenstein, Jacob D. (1981). "Universal upper bound on the entropy-to-energy ratio for bounded systems". Physical Review D 23 (2): 287–298. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.23.287. Bibcode: 1981PhRvD..23..287B. http://www.phys.huji.ac.il/~bekenste/PRD23-287-1981.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bekenstein, Jacob D. (2005). "How does the Entropy/Information Bound Work?". Foundations of Physics 35 (11): 1805–1823. doi:10.1007/s10701-005-7350-7. Bibcode: 2005FoPh...35.1805B.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bekenstein, Jacob (2008). "Bekenstein bound". Scholarpedia 3 (10): 7374. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.7374. Bibcode: 2008SchpJ...3.7374B.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Bousso, Raphael (2004-02-12). "Bound states and the Bekenstein bound". Journal of High Energy Physics 2004 (2): 025. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2004/02/025. ISSN 1029-8479. Bibcode: 2004JHEP...02..025B.

- ↑ 't Hooft, G. (1993-10-19). "Dimensional reduction in quantum gravity". arXiv:gr-qc/9310026.

{{cite arXiv}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ↑ Jacobson, Ted (1995). "Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State". Physical Review Letters 75 (7): 1260–1263. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1260. PMID 10060248. Bibcode: 1995PhRvL..75.1260J. http://www.gravityresearchfoundation.org/pdf/awarded/1995/jacobson.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Lee Smolin, Three Roads to Quantum Gravity (New York, N.Y.: Basic Books, 2002), pp. 173 and 175, ISBN 0-465-07836-2, LCCN 2007-310371.

- ↑ Bousso, Raphael (1999). "Holography in general space-times". Journal of High Energy Physics 1999 (6): 028. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/1999/06/028. Bibcode: 1999JHEP...06..028B.

- ↑ Bousso, Raphael (1999). "A covariant entropy conjecture". Journal of High Energy Physics 1999 (7): 004. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/1999/07/004. Bibcode: 1999JHEP...07..004B.

- ↑ Bousso, Raphael (2000). "The holographic principle for general backgrounds". Classical and Quantum Gravity 17 (5): 997–1005. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/17/5/309. Bibcode: 2000CQGra..17..997B.

- ↑ Bekenstein, Jacob D. (2000). "Holographic bound from second law of thermodynamics". Physics Letters B 481 (2–4): 339–345. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(00)00450-0. Bibcode: 2000PhLB..481..339B.

- ↑ Bousso, Raphael (2002). "The holographic principle". Reviews of Modern Physics 74 (3): 825–874. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.74.825. Bibcode: 2002RvMP...74..825B. http://bib.tiera.ru/DVD-005/Bousso_R._The_holographic_principle_(2002)(en)(50s).pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ↑ Jacob D. Bekenstein, "Information in the Holographic Universe: Theoretical results about black holes suggest that the universe could be like a gigantic hologram", Scientific American, Vol. 289, No. 2 (August 2003), pp. 58-65. Mirror link.

- ↑ Bousso, Raphael; Flanagan, Éanna É.; Marolf, Donald (2003). "Simple sufficient conditions for the generalized covariant entropy bound". Physical Review D 68 (6): 064001. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.68.064001. Bibcode: 2003PhRvD..68f4001B.

- ↑ Bekenstein, Jacob D. (2004). "Black holes and information theory". Contemporary Physics 45 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1080/00107510310001632523. Bibcode: 2004ConPh..45...31B.

- ↑ Tipler, F. J. (2005). "The structure of the world from pure numbers". Reports on Progress in Physics 68 (4): 897–964. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/68/4/R04. Bibcode: 2005RPPh...68..897T. http://math.tulane.edu/~tipler/theoryofeverything.pdf.. Tipler gives a number of arguments for maintaining that Bekenstein's original formulation of the bound is the correct form. See in particular the paragraph beginning with "A few points ..." on p. 903 of the Rep. Prog. Phys. paper (or p. 9 of the arXiv version), and the discussions on the Bekenstein bound that follow throughout the paper.

- ↑ Casini, Horacio (2008). "Relative entropy and the Bekenstein bound". Classical and Quantum Gravity 25 (20): 205021. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/25/20/205021. Bibcode: 2008CQGra..25t5021C.

External links

- Jacob D. Bekenstein, "Bekenstein-Hawking entropy", Scholarpedia, Vol. 3, No. 10 (2008), p. 7375, doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.7375.

- Jacob D. Bekenstein's website at the Racah Institute of Physics, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which contains a number of articles on the Bekenstein bound.

|