Liouville field theory

In physics, Liouville field theory (or simply Liouville theory) is a two-dimensional conformal field theory whose classical equation of motion is a generalization of Liouville's equation.

Liouville theory is defined for all complex values of the central charge of its Virasoro symmetry algebra, but it is unitary only if

and its classical limit is

Although it is an interacting theory with a continuous spectrum, Liouville theory has been solved. In particular, its three-point function on the sphere has been determined analytically.

Introduction

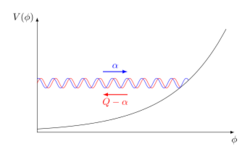

Liouville theory describes the dynamics of a field called the Liouville field, which is defined on a two-dimensional space. This field is not a free field due to the presence of an exponential potential

where the parameter is called the coupling constant. In a free field theory, the energy eigenvectors are linearly independent, and the momentum is conserved in interactions. In Liouville theory, momentum is not conserved.

Moreover, the potential reflects the energy eigenvectors before they reach , and two eigenvectors are linearly dependent if their momenta are related by the reflection

where the background charge is

While the exponential potential breaks momentum conservation, it does not break conformal symmetry, and Liouville theory is a conformal field theory with the central charge

Under conformal transformations, an energy eigenvector with momentum transforms as a primary field with the conformal dimension by

The central charge and conformal dimensions are invariant under the duality

The correlation functions of Liouville theory are covariant under this duality, and under reflections of the momenta. These quantum symmetries of Liouville theory are however not manifest in the Lagrangian formulation, in particular the exponential potential is not invariant under the duality.

Spectrum and correlation functions

Spectrum

The spectrum of Liouville theory is a diagonal combination of Verma modules of the Virasoro algebra,

where and denote the same Verma module, viewed as a representation of the left- and right-moving Virasoro algebra respectively. In terms of momenta,

corresponds to

The reflection relation is responsible for the momentum taking values on a half-line, instead of a full line for a free theory.

Liouville theory is unitary if and only if . The spectrum of Liouville theory does not include a vacuum state. A vacuum state can be defined, but it does not contribute to operator product expansions.

Fields and reflection relation

In Liouville theory, primary fields are usually parametrized by their momentum rather than their conformal dimension, and denoted . Both fields and correspond to the primary state of the representation , and are related by the reflection relation

where the reflection coefficient is[1]

(The sign is if and otherwise, and the normalization parameter is arbitrary.)

Correlation functions and DOZZ formula

For , the three-point structure constant is given by the DOZZ formula (for Dorn–Otto[2] and Zamolodchikov–Zamolodchikov[3]),

where the special function is a kind of multiple gamma function.

For , the three-point structure constant is[1]

where

-point functions on the sphere can be expressed in terms of three-point structure constants, and conformal blocks. An -point function may have several different expressions: that they agree is equivalent to crossing symmetry of the four-point function, which has been checked numerically[3][4] and proved analytically.[5][6]

Liouville theory exists not only on the sphere, but also on any Riemann surface of genus . Technically, this is equivalent to the modular invariance of the torus one-point function. Due to remarkable identities of conformal blocks and structure constants, this modular invariance property can be deduced from crossing symmetry of the sphere four-point function.[7][4]

Uniqueness of Liouville theory

Using the conformal bootstrap approach, Liouville theory can be shown to be the unique conformal field theory such that[1]

- the spectrum is a continuum, with no multiplicities higher than one,

- the correlation functions depend analytically on and the momenta,

- degenerate fields exist.

Lagrangian formulation

Action and equation of motion

Liouville theory is defined by the local action

where is the metric of the two-dimensional space on which the theory is formulated, is the Ricci scalar of that space, and is the Liouville field. The parameter , which is sometimes called the cosmological constant, is related to the parameter that appears in correlation functions by

The equation of motion associated to this action is

where is the Laplace–Beltrami operator. If is the Euclidean metric, this equation reduces to

which is equivalent to Liouville's equation.

Once compactified on a cylinder, Liouville field theory can be equivalently formulated as a worldline theory.[8]

Conformal symmetry

Using a complex coordinate system and a Euclidean metric

the energy–momentum tensor's components obey

The non-vanishing components are

Each one of these two components generates a Virasoro algebra with the central charge

For both of these Virasoro algebras, a field is a primary field with the conformal dimension

For the theory to have conformal invariance, the field that appears in the action must be marginal, i.e. have the conformal dimension

This leads to the relation

between the background charge and the coupling constant. If this relation is obeyed, then is actually exactly marginal, and the theory is conformally invariant.

Path integral

The path integral representation of an -point correlation function of primary fields is

It has been difficult to define and to compute this path integral. In the path integral representation, it is not obvious that Liouville theory has exact conformal invariance, and it is not manifest that correlation functions are invariant under and obey the reflection relation. Nevertheless, the path integral representation can be used for computing the residues of correlation functions at some of their poles as Dotsenko–Fateev integrals in the Coulomb gas formalism, and this is how the DOZZ formula was first guessed in the 1990s. It is only in the 2010s that a rigorous probabilistic construction of the path integral was found, which led to a proof of the DOZZ formula[9] and the conformal bootstrap.[6][10]

Relations with other conformal field theories

Some limits of Liouville theory

When the central charge and conformal dimensions are sent to the relevant discrete values, correlation functions of Liouville theory reduce to correlation functions of diagonal (A-series) Virasoro minimal models.[1]

On the other hand, when the central charge is sent to one while conformal dimensions stay continuous, Liouville theory tends to Runkel–Watts theory, a nontrivial conformal field theory (CFT) with a continuous spectrum whose three-point function is not analytic as a function of the momenta.[11] Generalizations of Runkel-Watts theory are obtained from Liouville theory by taking limits of the type .[4] So, for , two distinct CFTs with the same spectrum are known: Liouville theory, whose three-point function is analytic, and another CFT with a non-analytic three-point function.

WZW models

Liouville theory can be obtained from the Wess–Zumino–Witten model by a quantum Drinfeld–Sokolov reduction. Moreover, correlation functions of the model (the Euclidean version of the WZW model) can be expressed in terms of correlation functions of Liouville theory.[12][13] This is also true of correlation functions of the 2d black hole coset model.[12] Moreover, there exist theories that continuously interpolate between Liouville theory and the model.[14]

Conformal Toda theory

Liouville theory is the simplest example of a Toda field theory, associated to the Cartan matrix. More general conformal Toda theories can be viewed as generalizations of Liouville theory, whose Lagrangians involve several bosons rather than one boson , and whose symmetry algebras are W-algebras rather than the Virasoro algebra.

Supersymmetric Liouville theory

Liouville theory admits two different supersymmetric extensions called supersymmetric Liouville theory and supersymmetric Liouville theory.[15]

Relations with integrable models

Sinh-Gordon model

In flat space, the sinh-Gordon model is defined by the local action:

The corresponding classical equation of motion is the sinh-Gordon equation. The model can be viewed as a perturbation of Liouville theory. The model's exact S-matrix is known in the weak coupling regime , and it is formally invariant under . However, it has been argued that the model itself is not invariant.[16]

Applications

Liouville gravity

In two dimensions, Liouville theory can be used to build a quantum theory of gravity called Liouville gravity. It should not be confused[17][18] with the CGHS model or Jackiw–Teitelboim gravity.

In two dimensions, the Einstein-Hilbert action is topological, i.e. it is proportional to the Euler characteristic. Nevertheless, after quantization, general relativity is no longer topological, because of the Weyl anomaly: under a rescaling of the metric , while the action is invariant, the functional integration measure is not, and gives rise to a term proportional to the Liouville action for . This leads to the construction of Liouville gravity as a product of three CFTs: Liouville theory for the gravitational sector, Faddeev-Popov ghosts for Weyl invariance (viewed as a gauge symmetry), and an arbitrary CFT that describes matter. The central charges of these CFTs must sum to zero in order to cancel the Weyl anomaly, and ensure that the quantum theory is topological.[15]

The observables of Liouville gravity are correlation numbers: correlation functions of the product CFT, integrated over the moduli. Correlation numbers can be computed explicitly in some examples, such as the Virasoro minimal string.[19] Correlation numbers at fixed Euler characteristic are the coefficients of quantum gravity correlators, when expanded in powers of the gravitational constant.

String theory

Liouville theory appears in the context of string theory when trying to formulate a non-critical version of the theory in the path integral formulation.[20] The theory also appears as the description of bosonic string theory in two spacetime dimensions with a linear dilaton and a tachyon background. The tachyon field equation of motion in the linear dilaton background requires it to take an exponential solution. The Polyakov action in this background is then identical to Liouville field theory, with the linear dilaton being responsible for the background charge term while the tachyon contributing the exponential potential.[21]

Random energy models

There is an exact mapping between Liouville theory with , and certain log-correlated random energy models.[22] These models describe a thermal particle in a random potential that is logarithmically correlated. In two dimensions, such potential coincides with the Gaussian free field. In that case, certain correlation functions between primary fields in the Liouville theory are mapped to correlation functions of the Gibbs measure of the particle. This has applications to extreme value statistics of the two-dimensional Gaussian free field, and allows to predict certain universal properties of the log-correlated random energy models (in two dimensions and beyond).

Other applications

Liouville theory is related to other subjects in physics and mathematics, such as three-dimensional general relativity in negatively curved spaces, the uniformization problem of Riemann surfaces, and other problems in conformal mapping. It is also related to instanton partition functions in a certain four-dimensional superconformal gauge theories by the AGT correspondence.

Naming confusion for c ≤ 1

Liouville theory with first appeared as a model of time-dependent string theory under the name timelike Liouville theory.[23] It has also been called a generalized minimal model.[24] It was first called Liouville theory when it was found to actually exist, and to be spacelike rather than timelike.[4] As of 2022, not one of these three names is universally accepted.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ribault, Sylvain (2014). "Conformal field theory on the plane". arXiv:1406.4290 [hep-th].

- ↑ Dorn, H.; Otto, H.-J. (1994). "Two and three point functions in Liouville theory". Nucl. Phys. B 429 (2): 375–388. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(94)00352-1. Bibcode: 1994NuPhB......375D.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zamolodchikov, A.; Zamolodchikov, Al. (1996). "Conformal bootstrap in Liouville field theory". Nuclear Physics B 477 (2): 577–605. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(96)00351-3. Bibcode: 1996NuPhB.477..577Z.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Ribault, Sylvain; Santachiara, Raoul (2015). "Liouville theory with a central charge less than one". Journal of High Energy Physics 2015 (8): 109. doi:10.1007/JHEP08(2015)109. Bibcode: 2015JHEP...08..109R.

- ↑ Teschner, J (2003). "A lecture on the Liouville vertex operators". International Journal of Modern Physics A 19 (2): 436–458. doi:10.1142/S0217751X04020567. Bibcode: 2004IJMPA..19S.436T.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Guillarmou, C; Kupiainen, A; Rhodes, R; V, Vargas (2020). "Conformal Bootstrap in Liouville Theory". arXiv:2005.11530 [math.PR].

- ↑ Hadasz, Leszek; Jaskolski, Zbigniew; Suchanek, Paulina (2010). "Modular bootstrap in Liouville field theory". Physics Letters B 685 (1): 79–85. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.01.036. Bibcode: 2010PhLB..685...79H.

- ↑ Andrei Ioan, Dogaru; Campos Delgado, Ruben (2022). "Cylinder quantum field theories at small coupling". J. High Energy Phys. 2022 (10): 110. doi:10.1007/JHEP10(2022)110.

- ↑ Kupiainen, Antti; Rhodes, Rémi; Vargas, Vincent (2017). "Integrability of Liouville theory: Proof of the DOZZ Formula". arXiv:1707.08785 [math.PR].

- ↑ Guillarmou, Colin; Kupiainen, Antti; Rhodes, Rémi; Vargas, Vincent (2021-12-29). "Segal's axioms and bootstrap for Liouville Theory". arXiv:2112.14859v1 [math.PR].

- ↑ Schomerus, Volker (2003). "Rolling Tachyons from Liouville theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2003 (11): 043. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2003/11/043. Bibcode: 2003JHEP...11..043S.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ribault, Sylvain; Teschner, Joerg (2005). "H(3)+ correlators from Liouville theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2005 (6): 014. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2005/06/014. Bibcode: 2005JHEP...06..014R.

- ↑ Hikida, Yasuaki; Schomerus, Volker (2007). "H^+_3 WZNW model from Liouville field theory". Journal of High Energy Physics 2007 (10): 064. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2007/10/064. Bibcode: 2007JHEP...10..064H.

- ↑ Ribault, Sylvain (2008). "A family of solvable non-rational conformal field theories". Journal of High Energy Physics 2008 (5): 073. doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2008/05/073. Bibcode: 2008JHEP...05..073R.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Nakayama, Yu (2004). "Liouville Field Theory: A Decade After the Revolution". International Journal of Modern Physics A 19 (17n18): 2771–2930. doi:10.1142/S0217751X04019500. Bibcode: 2004IJMPA..19.2771N.

- ↑ Bernard, Denis; LeClair, André (2021-12-10). "The sinh-Gordon model beyond the self dual point and the freezing transition in disordered systems". Journal of High Energy Physics 2022 (5): 22. doi:10.1007/JHEP05(2022)022. Bibcode: 2022JHEP...05..022B.

- ↑ Grumiller, Daniel; Kummer, Wolfgang; Vassilevich, Dmitri (October 2002). "Dilaton Gravity in Two Dimensions". Physics Reports 369 (4): 327–430. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00267-3. Bibcode: 2002PhR...369..327G. https://cds.cern.ch/record/549532.

- ↑ Grumiller, Daniel; Meyer, Rene (2006). "Ramifications of Lineland". Turkish Journal of Physics 30 (5): 349–378. Bibcode: 2006TJPh...30..349G. http://mistug.tubitak.gov.tr/bdyim/abs.php?dergi=fiz&rak=0604-8.

- ↑ Collier, Scott; Eberhardt, Lorenz; Mühlmann, Beatrix; Rodriguez, Victor A. (2024-02-26). "The Virasoro minimal string". SciPost Physics (Stichting SciPost) 16 (2). doi:10.21468/scipostphys.16.2.057. ISSN 2542-4653.

- ↑ Polyakov, A.M. (1981). "Quantum geometry of bosonic strings". Physics Letters B 103 (3): 207–210. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(81)90743-7. Bibcode: 1981PhLB..103..207P.

- ↑ Polchinski, J. (1998). "9". String Theory Volume I: An Introduction to the Bosonic String. Cambridge University Press. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-0-14-311379-9.

- ↑ Cao, Xiangyu; Doussal, Pierre Le; Rosso, Alberto; Santachiara, Raoul (2018-01-30). "Operator Product Expansion in Liouville Field Theory and Seiberg type transitions in log-correlated Random Energy Models". Physical Review E 97 (4). doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.97.042111. PMID 29758633. Bibcode: 2018PhRvE..97d2111C.

- ↑ Strominger, Andrew; Takayanagi, Tadashi (2003). "Correlators in Timelike Bulk Liouville Theory". Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 7 (2): 369–379. doi:10.4310/atmp.2003.v7.n2.a6. Bibcode: 2003hep.th....3221S. https://projecteuclid.org/download/pdf_1/euclid.atmp/1112627637.

- ↑ Zamolodchikov, Al (2005). "On the Three-point Function in Minimal Liouville Gravity". Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 142 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1007/s11232-005-0048-3. Bibcode: 2005TMP...142..183Z.

External links

- Mathematicians Prove 2D Version of Quantum Gravity Really Works, Quanta Magazine article by Charlie Wood, June 2021.

- An Introduction to Liouville Theory, Talk at Institute for Advanced Study by Antti Kupiainen, May 2018.

|