Chemistry:Daclatasvir

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dəˈklætəsvɪər/ də-KLAT-əs-veer |

| Trade names | Daklinza |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a615044 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 67%[3] |

| Protein binding | 99%[3] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A |

| Elimination half-life | 12–15 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal (53% as unchanged drug), kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C40H50N8O6 |

| Molar mass | 738.890 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Daclatasvir, sold under the brand name Daklinza, is an antiviral medication used in combination with other medications to treat hepatitis C (HCV).[4] The other medications used in combination include sofosbuvir, ribavirin, and interferon, vary depending on the virus type and whether the person has cirrhosis.[2] It is taken by mouth.[4]

Common side effects when used with sofusbivir and daclatasvir include headache, feeling tired, and nausea.[3] With daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, and ribavirin the most common side effects are headache, feeling tired, nausea, and red blood cell breakdown.[3] It should not be used with St. John's wort, rifampin, or carbamazepine.[4] It works by inhibiting the HCV protein NS5A.[2]

Daclatasvir was approved for use in the European Union in 2014, and the United States and India in 2015.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6]

The brand Daklinza is being withdrawn by Bristol Myers Squibb in countries where the drug is not typically prescribed, and Bristol Myers Squibb says it will not enforce its patents in those countries.[7]

Medical use

Daclatasvir is used only in combination therapy for the treatment of hepatitis C genotype 1, 3, or 4 infections; the agents used in combination, which include sofosbuvir, ribavirin, and interferon, vary based on the virus genotype, whether the person has cirrhosis and if a liver transplantation took place.[8][2][9]

It is not known whether daclatasvir passes into breastmilk or has any effect on infants.[3]

Adverse effects

There is a serious risk of bradycardia when daclatasvir is used with sofosbuvir and amiodarone.[3]

Because it has not been extensively studied as a single agent, it is unknown what specific side effects are linked to this medication alone. Adverse events on daclatasvir have only been reported on combination therapy with sofosbuvir or triple therapy with sofosbuvir/ribavirin.[3]

Common adverse events occurring in >5% of people on combination therapy (sofosbuvir + daclatasvir) include headache and fatigue; in triple therapy (daclatasvir + sofosbuvir + ribavirin) the most common adverse events (>10%) include headache, fatigue, nausea and hemolytic anemia.[3]

Daclatasvir could cause hepatitis B re-activation in people co-infected with hepatitis B and C viruses. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended screening all people for hepatitis B before starting daclatasvir for hepatitis C in order to minimize the risk of hepatitis B reactivation.[10]

Interactions

Concomitant use of drugs that are strong inducers of the cytochrome P450 CYP3A is contraindicated due to decreased therapeutic effect and resistance of drug.[3] Some common drugs that are strong CYP3A inducers include dexamethasone, phenytoin, carbamazepine, rifampin and St. John's Wort.[3]

Daclatasvir is a CYP3A and p-glycoprotein substrate, therefore, drugs that are strong inducers or inhibitors of these enzyme will interfere with daclatasvir levels in the body.[3] Dose modifications are made with concomitant use of daclatasvir and drugs that affect CYP3A or p-gp. When taking daclatasvir with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, the dose of daclatasvir is increased to overcome CYP3A induction. The dose for daclatasvir should be lowered when taking with antifungals, such as ketoconazole. Currently, there are no required dosage adjustments with concurrent use of daclatasvir and immunosuppressants, narcotic analgesics, antidepressants, sedatives, and cardiovascular agents.[11]

Concurrent use with amiodarone, sofosbuvir and daclatasvir has may result in an increased risk for serious slowing of the heart rate.[3]

Pharmacology

The role of NS5A in HCV replication

NS5A is a zinc-binding protein dimer serving as a regulator in the replication cycle of HCV. It contains an amino-terminal amphipathic helix and three different domains with different binding affinities. The N-terminus binds to cellular membranes and is essential for the formation of replication complexes. Domain 1 (amino acid 401–60012) is an RNA binding region of NS5A and domain 2 serves in the RNA replication. Virus assembly is associated with domain 3.[12]

NS5A not only binds to cellular membranes, other non-structural proteins of the HCV replication-complex and viral RNA, but also to co-factors like PI4KA. PI4KA is a kinase, which phosphorylates a hydroxyl group of phosphatidylinositol in its inositol-ring at position four. This phosphorylation generates phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), a docking site normally located at the Golgi membrane. PI4P is necessary for the recruitment of effector proteins participating in transport vesicles of lipid transfer. Resulting from that PI4P is crucial for maintaining the Golgi membrane structure and Golgi-secretion.[13]

By binding PI4KA on its domain 1 and accumulating PI4P away from the Golgi apparatus, NS5A induces the formation of a membranous web, a membrane structure arising from the endoplasmic reticulum via recruitment of lipid vesicles. The replication complex of HCV is located on this web-like structure. Out of these membranes and lipid drops, which had been recruited via PI4P, the virions can be assembled after viral-RNA replication.[14]

The RNA replication and assembly of virions depend on the ratio between two different forms of NS5A. Depending on the phosphorylation rate of NS5A, it is differentiated between NS5A (p56) and the hyperphosphorylated NS5A (p58). A higher rate of p58 seems to induce HCV assembly, whereas a lack of p58 leads to RNA replication. But the actual role of phosphorylation of NS5A is not clear.[15][16]

However, NS5A does not only regulate HCV replication and assembly, it also inhibits apoptosis, so the infected cell cannot disintegrate by itself and contain the infection, as cells normally do. Because of the lack of apoptosis, mutations within the cellular genome also do not trigger cells death. This causes the promotion of tumours.[15]

Mechanism of action

NS5A contains a binding pocket in domain 1, where daclatasvir can insert. Because of the symmetric and amino acid related structure of daclatasvir, it comes to H-bond interactions between daclatasvir and the amino acids of the binding pocket. That causes a structural modification of NS5A, leading to a loss of action and resulting in an inhibition of virion formation.[17]

By altering the structure of NS5A, the recruitment of PI4KA and therefore the accumulation of PI4P get disabled. New lipid-drops and membranous components can no longer get recruited by PI4P in the membranous web and the web can no longer maintain. But it is important to mention that daclatasvir does not inhibit PI4KA directly, because it was observed that in cells, which were treated with daclatasvir, PI4P is still present in the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus. Daclatasvir also does not inhibit the initial PI4KA delocalization induced by NS5A because it was witnessed that daclatasvir had no impact on the function of NS5A within cells expressing only NS5A. It is likely that daclatasvir merely inhibits functions of NS5A associated with other proteins within the HCV replication complex just like the RNA-replicase NS4B. Concluding, daclatasvir presumably only inhibits PI4P hyper-accumulation in the context of full HCV polypeptide expression.[citation needed]

This phenomenon is associated with the structure of domain 1 of NS5A. It was observed that domain 1 has two different conformations. Daclatasvir binds to one of these and as a result, locks domain 1 in this conformation. Though, NS5A is still able to bind PI4KA, what can explain the remaining function of NS5A in uninfected cells mentioned before. The second conformation of domain 1, which appears in non-treated cells, is then most likely to be associated with PI4P hyper-accumulation that is necessary for the formation and maintainment of the replication-complex and membranous web. So, PI4KA can still interact with NS5A, but due to the structural blockade, NS5A is not able to activate PI4KA as efficiently as normal.[16]

The inhibition of hyper-accumulation of PI4P results in the collapse of the membranous web and the formation of large aggregated structures formed out of the proteins of the replication complex. Moreover, NS5A seems to delocalize from the membranous web to lipid drops within the cytosol.[15] Resulting from this observation, it is likely that the HCV replication-complex and virion hulls still get formed but are highly impaired by the treatment with daclatasvir.[16]

Furthermore, it has been observed, that the treatment of HCV infected cells with daclatasvir leads to a lack of the hyper-phosphorylated form of NS5A (p58). It is not clear if the formation of p58 is directly inhibited by daclatasvir or if it is just a side effect. But it is likely that the lack of p58 is crucial for the inhibition of virion assembly.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

Daclatasvir reaches steady state in human subjects after about 4 days of once-daily 60 mg oral administration, with a peak dose in concentration occurring about 2 hours after administration.[3] It comes in the form of an oral tablet, with a bioavailability of 67%.[3] Daclatasvir is predominantly metabolized by the liver enzyme CYP3A4, and is also a P-gp substrate.[3] It is highly protein bound. Protein binding was measured to be around 99% in people dosed multiple times with daclatasvir independent of dose strength.[3] Daclatasvir has a volume of distribution of 47L following an oral dose of 60 mg and an IV dose of 100 μg.[3]

History

Daklinza was discovered by scientists at Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS); the precursor was identified using phenotypic screening in which the GT-1b replicon system was implemented in Huh7 cells and bovine viral diarrhea virus also in Huh7 cells was used as a counterscreen for specificity.[17] Bristol Myers Squibb also developed the drug, with the first Phase I trial publishing in 2010.[17]

It was approved for use in Europe in August 2014, in the US in July 2015, and in India in December 2015; it was first in the class of NS5A inhibitors to reach the market.[5]

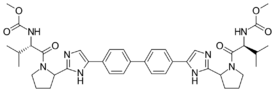

Synthesis

The daclatasvir molecule contains the two amino acids proline and valine in their natural L-form which makes it easier to synthesize in the right stereo configuration.[17] The following describes one exemplary mechanism of synthesizing daclatasvir as its free base. The first step is a Friedel-Crafts acylation of biphenyl with chloroacetyl chloride and aluminium chloride used as a catalyst. As biphenyl is a solid crystal it is solved in 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE). The mixture of chloroacetyl chloride and aluminium chloride is also used in a solution with DCE. To separate the product from the other compounds the outcoming reaction mixture is treated with 2N HCl solution.[citation needed]

In the next step, the symmetrically acetylated product from the first step reacts with an N-methoxycarbonyl dipeptide in an esterification reaction. The dipeptide consists of the amino acids L-proline and L-valine and is solved in acetonitrile (MeCN). While the amino terminus of valine is protected by the methoxycarbonyl group the carboxy terminus of proline reacts with the product of step one forming the esterified product of both chemicals. In this reaction triethylamine works as a basic solvent.[citation needed]

As a final step, the present molecule reacts with ammonium acetate in water forming the imidazole heterocycles on both sides of the molecule.[18]

Another option is to esterify it with boc-protected proline first, then form the imidazole heterocycles with ammonium acetate and add valine in the end after acidic deprotection of prolines N-terminus. In both cases, the final product is the daclatasvir free base. In the drug, daclatasvir is present in the hydrochloride salt form.[17]

Society and culture

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[6]

Economics

In December 2014, Bristol Myers Squibb announced that it would offer the drug for sale at different prices in different countries, depending on the level of economic development, and that it would license the drug to generics manufacturers for sale in the developing world.[19][20]

As of January 2016, a twelve-week course cost around $63,000 in the US, around $39,000 in the UK, around $37,000 in France, and $525 in Egypt.[21]

Research

Daclatasvir has been tested in combination regimens with pegylated interferon and ribavirin,[22] as well as with other direct-acting antiviral agents including asunaprevir and sofosbuvir.[23]

References

- ↑ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2015". 21 June 2022. https://www.tga.gov.au/prescription-medicines-registration-new-chemical-entities-australia-2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Daklinza film-coated tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". Electronic Medicines Compendium. September 2016. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29129.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 "Daklinza (daclatasvir) tablets, for oral useInitial U.S. Approval: 2015". 16 October 2019. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/archives/fdaDrugInfo.cfm?archiveid=433227.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Daclatasvir Dihydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/daclatasvir-dihydrochloride.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Hepatitis C Treatment Snapshots: Daclatasvir". amFAR TreatAsia. February 2016. http://www.amfar.org/uploadedFiles/_amfarorg/Around_the_World/TREAT_Asia/TA_Snapshots_Daclatasvir_for%20online.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Important information about the discontinuation of Daklinza". 9 March 2020. https://www.bms.com/patient-and-caregivers/our-medicines/discontinuation-of-daklinza.html.

- ↑ "Daklinza, INN-daclatasvir". https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/daklinza-epar-productinformation_en.pdf.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Daclatasvir-sofosbuvir combination therapy with or without ribavirin for hepatitis C virus infection: from the clinical trials to real life". Hepatic Medicine: Evidence and Research 8: 21–6. March 2016. doi:10.2147/HMER.S62014. PMID 27019602.

- ↑ "Direct-acting antivirals indicated for treatment of hepatitis C (interferon-free)". 17 September 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/direct-acting-antivirals-indicated-treatment-hepatitis-c-interferon-free.

- ↑ "A Review of Daclatasvir Drug-Drug Interactions". Advances in Therapy 33 (11): 1867–1884. November 2016. doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0407-5. PMID 27664109.

- ↑ "Hepatitis C virus and host cell lipids: an intimate connection". RNA Biology 8 (2): 258–69. 2011. doi:10.4161/rna.8.2.15011. PMID 21593584.

- ↑ "Structural Basis for Regulation of Phosphoinositide Kinases and Their Involvement in Human Disease". Molecular Cell 71 (5): 653–673. September 2018. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.005. PMID 30193094.

- ↑ "Phosphoinositides in the hepatitis C virus life cycle". Viruses 4 (10): 2340–58. October 2012. doi:10.3390/v4102340. PMID 23202467.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "NS5A inhibitors in the treatment of hepatitis C". Journal of Hepatology 59 (2): 375–82. August 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.030. PMID 23567084.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Daclatasvir inhibits hepatitis C virus NS5A motility and hyper-accumulation of phosphoinositides". Virology 476: 168–179. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2014.12.018. PMID 25546252.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 "Discovery of daclatasvir, a pan-genotypic hepatitis C virus NS5A replication complex inhibitor with potent clinical effect". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 57 (12): 5057–71. June 2014. doi:10.1021/jm500335h. PMID 24749835.

- ↑ "Integrated multi-step continuous flow synthesis of daclatasvir without intermediate purification and solvent exchange". Reaction Chemistry & Engineering 5 (11): 2109–14. 2020. doi:10.1039/d0re00323a.

- ↑ "Access to hepatitis C medicines". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93 (11): 799–805. November 2015. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.157784. PMID 26549908. PMC 4622162. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/93/11/15-157784/en/.

- ↑ "MSF Briefing Document May 2015". Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. https://www.msfaccess.org/sites/default/files/MSF_assets/HepC/Docs/HepC_brief_OvercomingbarriersToAccess_ENG_2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C". Journal of Virus Eradication 2 (1): 28–31. January 2016. doi:10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30691-9. PMID 27482432.

- ↑ "Daclatasvir combined with peginterferon-α and ribavirin for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: a meta-analysis". SpringerPlus 5 (1): 1569. 15 September 2016. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3218-x. PMID 27652142.

- ↑ "Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for previously treated or untreated chronic HCV infection". The New England Journal of Medicine 370 (3): 211–21. January 2014. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1306218. PMID 24428467.

External links

- "Daclatasvir". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/daclatasvir.

- "Daclatasvir dihydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/daclatasvir%20dihydrochloride.

|