Chemistry:Hydroxychloroquine

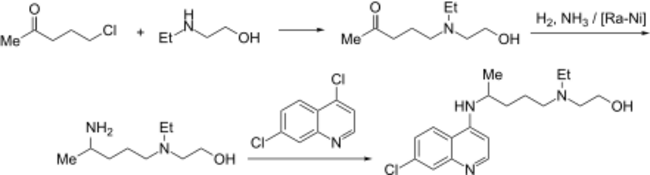

Skeletal formula of hydroxychloroquine | |

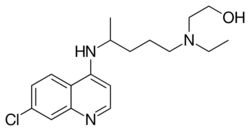

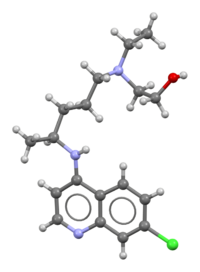

Ball-and-stick model of the hydroxychloroquine freebase molecule | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Plaquenil, others |

| Other names | HCQ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601240 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable (74% on average); Tmax = 2–4.5 hours |

| Protein binding | 45% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 32–50 days |

| Excretion | Mostly kidney (23–25% as unchanged drug), also biliary (<10%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H26ClN3O |

| Molar mass | 335.88 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Hydroxychloroquine, sold under the brand name Plaquenil among others, is a medication used to prevent and treat malaria in areas where malaria remains sensitive to chloroquine. Other uses include treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and porphyria cutanea tarda. It is taken by mouth, often in the form of hydroxychloroquine sulfate.[2]

Common side effects may include vomiting, headache, blurred vision, and muscle weakness.[2] Severe side effects may include allergic reactions, retinopathy, and irregular heart rate.[2][3] Although all risk cannot be excluded, it remains a treatment for rheumatic disease during pregnancy.[4] Hydroxychloroquine is in the antimalarial and 4-aminoquinoline families of medication.[2]

Hydroxychloroquine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1955.[2] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] In 2020, it was the 126th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with 4.99 million prescriptions.[6][7]

Hydroxychloroquine has been studied for an ability to prevent and treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), but clinical trials found it ineffective for this purpose and a possible risk of dangerous side effects.[8] Among studies that deemed hydroxychloroquine intake to cause harmful side effects, a publication by The Lancet was retracted due to data flaws.[9] The speculative use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 threatens its availability for people with established indications.[10]

Medical uses

Hydroxychloroquine treats rheumatic disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and porphyria cutanea tarda, and certain infections such as Q fever and certain types of malaria.[2] It is considered the first-line treatment for systemic lupus erythematosus.[11] Certain types of malaria, resistant strains, and complicated cases require different or additional medication.[2]

It is widely used to treat primary Sjögren syndrome but does not appear to be effective.[12] Hydroxychloroquine is widely used in the treatment of post-Lyme arthritis. It may have both an anti-spirochete activity and an anti-inflammatory activity, similar to the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.[13]

Contraindications

The drug label advises that hydroxychloroquine should not be prescribed to individuals with known hypersensitivity to 4-aminoquinoline compounds.[14] There are several other contraindications,[15][16] and caution is required if the person considered for treatment has certain heart conditions, diabetes, or psoriasis.

Adverse effects

Hydroxychloroquine has a narrow therapeutic index, meaning there is little difference between toxic and therapeutic doses.[17] The most common adverse effects are nausea, stomach cramps, and diarrhea. Other common adverse effects include itching and headache.[10] The most serious adverse effects affect the eye, with dose-related retinopathy as a concern even after hydroxychloroquine use is discontinued.[2] Serious reported neuropsychiatric adverse effects of hydroxychloroquine use include agitation, mania, difficulty sleeping, hallucinations, psychosis, catatonia, paranoia, depression, and suicidal thoughts.[10] In rare situations, hydroxychloroquine has been implicated in cases of serious skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.[10] Reported blood abnormalities with its use include lymphopenia, eosinophilia, and atypical lymphocytosis.[10]

For short-term treatment of acute malaria, adverse effects can include abdominal cramps, diarrhea, heart problems, reduced appetite, headache, nausea and vomiting.[2] Other adverse effects noted with short-term use of Hydroxychloroquine include low blood sugar and QT interval prolongation.[18] Idiosyncratic hypersensitivity reactions have occurred.[10]

For prolonged treatment of lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, adverse effects include the acute symptoms, plus altered eye pigmentation, acne, anemia, bleaching of hair, blisters in mouth and eyes, blood disorders, cardiomyopathy,[18] convulsions, vision difficulties, diminished reflexes, emotional changes, excessive coloring of the skin, hearing loss, hives, itching, liver problems or liver failure, loss of hair, muscle paralysis, weakness or atrophy, nightmares, psoriasis, reading difficulties, tinnitus, skin inflammation and scaling, skin rash, vertigo, weight loss, and occasionally urinary incontinence.[2] Hydroxychloroquine can worsen existing cases of both psoriasis and porphyria.[2]

Children may be especially vulnerable to developing adverse effects from hydroxychloroquine overdoses.[2]

Eyes

One of the most serious side effects is retinopathy (generally with chronic use).[2][19] People taking 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine or less per day generally have a negligible risk of macular toxicity, whereas the risk begins to increase when a person takes the medication over five years or has a cumulative dose of more than 1000 grams. The daily safe maximum dose for eye toxicity can be estimated from a person's height and weight.[20] Macular toxicity is related to the total cumulative dose rather than the daily dose. Regular eye screening, even in the absence of visual symptoms, is recommended to begin when either of these risk factors occurs.[21]

Toxicity from hydroxychloroquine may be seen in two distinct areas of the eye: the cornea and the macula. The cornea may become affected (relatively commonly) by an innocuous cornea verticillata or vortex keratopathy and is characterized by whorl-like corneal epithelial deposits. These changes bear no relationship to dosage and are usually reversible on cessation of hydroxychloroquine.

The macular changes are potentially serious. Advanced retinopathy is characterized by reduction of visual acuity and a "bull's eye" macular lesion which is absent in early involvement.

Overdose

Overdoses of hydroxychloroquine are extremely rare, but extremely toxic.[10] Eight people are known to have overdosed since the drug's introduction in the mid-1950s, of which three have died.[22][23] Chloroquine has a risk of death in overdose in adults of about 20%, while hydroxychloroquine is estimated to be two or threefold less toxic.[24]

Serious signs and symptoms of overdose generally occur within an hour of ingestion.[24] These may include sleepiness, vision changes, seizures, coma, stopping of breathing, and heart problems such as ventricular fibrillation and low blood pressure.[10][24][25] Loss of vision may be permanent.[26] Low blood potassium, to levels of 1 to 2 mmol/L, may also occur.[24][27] Cardiovascular abnormalities such as QRS complex widening and QT interval prolongation may also occur.[10]

Treatment recommendations include early mechanical ventilation, heart monitoring, and activated charcoal.[24] Supportive treatment with intravenous fluids and vasopressors may be required with epinephrine being the vasopressor of choice.[24] Stomach pumping may also be used.[22] Sodium bicarbonate and hypertonic saline may be used in cases of severe QRS complex widening.[10] Seizures may be treated with benzodiazepines.[24] Intravenous potassium chloride may be required, however this may result in high blood potassium later in the course of the disease.[24] Dialysis does not appear to be useful.[24]

Detection

Hydroxychloroquine may be quantified in plasma or serum to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized victims or in whole blood to assist in a forensic investigation of a case of sudden or unexpected death. Plasma or serum concentrations are usually in a range of 0.1-1.6 mg/L during therapy and 6–20 mg/L in cases of clinical intoxication, while blood levels of 20–100 mg/L have been observed in deaths due to acute overdosage.[28]

Interactions

The drug transfers into breast milk.[1] There is no evidence that its use during pregnancy is harmful to the developing fetus and its use is not contraindicated in pregnancy.[10]

The concurrent use of hydroxychloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin appears to increase the risk for certain serious side effects with short-term use, such as an increased risk of chest pain, congestive heart failure, and mortality from cardiovascular causes.[18] Care should be taken if combined with medication altering liver function as well as aurothioglucose (Solganal), cimetidine (Tagamet) or digoxin (Lanoxin). Hydroxychloroquine can increase plasma concentrations of penicillamine which may contribute to the development of severe side effects. It enhances hypoglycemic effects of insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents. Dose altering is recommended to prevent profound hypoglycemia. Antacids may decrease the absorption of hydroxychloroquine. Both neostigmine and pyridostigmine antagonize the action of hydroxychloroquine.[29]

While there may be a link between hydroxychloroquine and hemolytic anemia in those with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, this risk may be low in those of African descent.[30]

Specifically, the US Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) drug label for hydroxychloroquine lists the following drug interactions:[14]

- Digoxin (wherein it may result in increased serum digoxin levels)

- Insulin or anti-diabetic medication (wherein it may enhance the effects of a hypoglycemic treatment)

- Drugs that prolong the QT interval such as methadone, and other arrhythmogenic drugs, as hydroxychloroquine prolongs the QT interval and may increase the risk of inducing serious abnormal heart rhythms (ventricular arrhythmias) if used concurrently.[3]

- Mefloquine and other drugs known to lower the seizure threshold (co-administration with other antimalarials known to lower the convulsion threshold may increase risk of convulsions)

- Antiepileptics (concurrent use may impair the antiepileptic activity)

- Methotrexate (combined use is unstudied and may increase the frequency of side effects)

- Cyclosporin (wherein an increased plasma cyclosporin level was reported when used together).

Pharmacology

Pharmacokinetics

Hydroxychloroquine has similar pharmacokinetics to chloroquine, with rapid gastrointestinal absorption, large distribution volume,[31] and elimination by the kidneys. Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2D6, 2C8, 3A4 and 3A5) metabolize hydroxychloroquine to N-desethylhydroxychloroquine.[32] Both agents also inhibit CYP2D6 activity and may interact with other medications that depend on this enzyme.[10]

Pharmacodynamics

Antimalarials are lipophilic weak bases and easily pass plasma membranes. The free base form accumulates in lysosomes (acidic cytoplasmic vesicles) and is then protonated,[33] resulting in concentrations within lysosomes up to 1000 times higher than in culture media. This increases the pH of the lysosome from four to six.[34] Alteration in pH causes inhibition of lysosomal acidic proteases causing a diminished proteolysis effect.[35] Higher pH within lysosomes causes decreased intracellular processing, glycosylation and secretion of proteins with many immunologic and nonimmunologic consequences.[36] These effects are believed to be the cause of a decreased immune cell functioning such as chemotaxis, phagocytosis and superoxide production by neutrophils.[37] Hydroxychloroquine is a weak diprotic base that can pass through the lipid cell membrane and preferentially concentrate in acidic cytoplasmic vesicles. The higher pH of these vesicles in macrophages or other antigen-presenting cells limits the association of autoantigenic (any) peptides with class II MHC molecules in the compartment for peptide loading and/or the subsequent processing and transport of the peptide-MHC complex to the cell membrane.[38]

Mechanism of action

Hydroxychloroquine increases[39] lysosomal pH in antigen-presenting cells[18] by two mechanisms: As a weak base, it is a proton acceptor and via this chemical interaction, its accumulation in lysozymes raises the intralysosomal pH, but this mechanism does not fully account for the effect of hydroxychloroquine on pH. Additionally, in parasites that are susceptible to hydroxychloroquine, it interferes with the endocytosis and proteolysis of hemoglobin and inhibits the activity of lysosomal enzymes, thereby raising the lysosomal pH by more than 2 orders of magnitude over the weak base effect alone.[40][41] In 2003, a novel mechanism was described wherein hydroxychloroquine inhibits stimulation of the toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 family receptors. TLRs are cellular receptors for microbial products that induce inflammatory responses through activation of the innate immune system.[42]

As with other quinoline antimalarial drugs, the antimalarial mechanism of action of quinine has not been fully resolved. The most accepted model is based on hydrochloroquinine and involves the inhibition of hemozoin biocrystallization, which facilitates the aggregation of cytotoxic heme. Free cytotoxic heme accumulates in the parasites, causing death.[43]

Hydroxychloroquine increases the risk of low blood sugar through several mechanisms. These include decreased clearance of the hormone insulin from the blood, increased insulin sensitivity, and increased release of insulin from the pancreas.[10]

History

After World War I, the German government sought alternatives to quinine as an anti-malarial. Chloroquine, a synthetic analogue with the same mechanism of action was discovered in 1934, by Hans Andersag and coworkers at the Bayer laboratories.[44][45]: 130–131 This was introduced into clinical practice in 1947 for the prophylactic treatment of malaria.[46] Researchers subsequently attempted to discover structural analogs with superior properties and one of these was hydroxychloroquine.[47]

Chemical synthesis

The first synthesis of hydroxychloroquine was disclosed in a patent filed by Sterling Drug in 1949.[48] In the final step, 4,7-dichloroquinoline was reacted with a primary amine which in turn had been made from the chloro-ketone shown:

Manufacturing

It is frequently sold as a sulfate salt known as hydroxychloroquine sulfate.[2] In the sulfate salt form, 200 mg is equal to 155 mg of the pure form.[2]

Brand names of hydroxychloroquine include Plaquenil, Hydroquin, Axemal (in India), Dolquine, Quensyl, and Quinoric.[49]

COVID-19

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Hydroxychloroquine Use During Pregnancy". 28 February 2020. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/hydroxychloroquine.html.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 "Hydroxychloroquine Sulfate Monograph for Professionals". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 20 March 2020. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/hydroxychloroquine-sulfate.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Guidance on patients at risk of drug-induced sudden cardiac death from off-label COVID-19 treatments". 25 March 2020. https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/mayo-clinic-provides-urgent-guidance-approach-to-identify-patients-at-risk-of-drug-induced-sudden-cardiac-death-from-use-of-off-label-covid-19-treatments/.

- ↑ "BSR and BHPR guideline on prescribing drugs in pregnancy and breastfeeding-Part I: standard and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and corticosteroids". Rheumatology 55 (9): 1693–7. September 2016. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kev404. PMID 26750124.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. World Health Organization. 2019.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Hydroxychloroquine – Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Hydroxychloroquine.

- ↑ "Chloroquine or Hydroxychloroquine". National Institutes of Health. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/antiviral-therapy/chloroquine-or-hydroxychloroquine-with-or-without-azithromycin/.

- ↑ "The Lancet retracts large study on hydroxychloroquine". NBC News. 4 June 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/lancet-retracts-large-study-hydroxychloroquine-n1225091.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 "Safety considerations with chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in the management of SARS-CoV-2 infection". CMAJ 192 (17): E450–E453. April 2020. doi:10.1503/cmaj.200528. PMID 32269021.

- ↑ "Hydroxychloroquine in dermatology: New perspectives on an old drug". The Australasian Journal of Dermatology 61 (2): e150–e157. May 2020. doi:10.1111/ajd.13168. PMID 31612996.

- ↑ "Is hydroxychloroquine effective in treating primary Sjogren's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 18 (1): 186. May 2017. doi:10.1186/s12891-017-1543-z. PMID 28499370.

- ↑ "Therapy for Lyme arthritis: strategies for the treatment of antibiotic-refractory arthritis". Arthritis and Rheumatism 54 (10): 3079–86. October 2006. doi:10.1002/art.22131. PMID 17009226.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Plaquenil- hydroxychloroquine sulfate tablet". 3 January 2020. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=34496b43-05a2-45fb-a769-52b12e099341.

- ↑ "Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine sulfate) dose, indications, adverse effects, interactions". https://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/Plaquenil-hydroxychloroquine-sulfate-1911.

- ↑ "Drugs & Medications". https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-5482/hydroxychloroquine-oral/details.

- ↑ "The Approved Dose of Ivermectin Alone is not the Ideal Dose for the Treatment of COVID-19". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 108 (4): 762–765. October 2020. doi:10.1002/cpt.1889. PMID 32378737.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Rethinking the role of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19". FASEB Journal 34 (5): 6027–6037. May 2020. doi:10.1096/fj.202000919. PMID 32350928.

- ↑ "Improving the risk-benefit relationship and informed consent for patients treated with hydroxychloroquine". Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 105: 191–4; discussion 195–7. December 2007. PMID 18427609.

- ↑ "Plaquenil Risk Calculators". https://www.eyedock.com/plaquenil-calcs.

- ↑ "Revised recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy". Ophthalmology 118 (2): 415–22. February 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.11.017. PMID 21292109.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs: The International Encyclopedia of Adverse Drug Reactions and Interactions. Elsevier. 2015. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-444-53716-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=NOKoBAAAQBAJ&dq=Hydroxychloroquine+overdose&pg=RA1-PA261.

- ↑ "Treatment of hydroxychloroquine overdose". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 19 (5): 420–4. September 2001. doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.25774. PMID 11555803.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 "Hydroxychloroquine overdose: case report and recommendations for management". European Journal of Emergency Medicine 15 (1): 16–8. February 2008. doi:10.1097/MEJ.0b013e3280adcb56. PMID 18180661.

- ↑ "Are 1-2 dangerous? Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine exposure in toddlers". The Journal of Emergency Medicine 28 (4): 437–43. May 2005. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.12.011. PMID 15837026.

- ↑ Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity at eMedicine

- ↑ Modern Medical Toxicology. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. 2012. p. 458. ISBN 978-93-5025-965-8. http://www.prip.edu.in/img/ebooks/VV-Pillay-Modern-Medical-Toxicology-4th-Edition.pdf#page=474. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 12th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2020, pp. 1024-1026.

- ↑ "Russian Register of Medicines: Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine) Film-coated Tablets for Oral Use. Prescribing Information" (in ru). Sanofi-Synthelabo. http://www.rlsnet.ru/tn_index_id_2615.htm.

- ↑ "Examination of Hydroxychloroquine Use and Hemolytic Anemia in G6PDH-Deficient Patients". Arthritis Care & Research 70 (3): 481–485. March 2018. doi:10.1002/acr.23296. PMID 28556555.

- ↑ "Mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine: implications for rheumatology". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology 16 (3): 155–166. March 2020. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0372-x. PMID 32034323.

- ↑ "New concepts in antimalarial use and mode of action in dermatology". Dermatologic Therapy 20 (4): 160–74. July 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8019.2007.00131.x. PMID 17970883.

- ↑ "Lysosomal sequestration of amine-containing drugs: analysis and therapeutic implications". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 96 (4): 729–46. April 2007. doi:10.1002/jps.20792. PMID 17117426.

- ↑ "Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 75 (7): 3327–31. July 1978. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. PMID 28524. Bibcode: 1978PNAS...75.3327O.

- ↑ "The effects of basic substances and acidic ionophores on the digestion of exogenous and endogenous proteins in mouse peritoneal macrophages". The Journal of Cell Biology 102 (3): 959–66. March 1986. doi:10.1083/jcb.102.3.959. PMID 3949884.

- ↑ "Effects of weakly basic amines on proteolytic processing and terminal glycosylation of secretory proteins in cultured rat hepatocytes". The Biochemical Journal 240 (3): 739–45. December 1986. doi:10.1042/bj2400739. PMID 3493770.

- ↑ "Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine inhibit multiple sites in metabolic pathways leading to neutrophil superoxide release". The Journal of Rheumatology 15 (1): 23–7. January 1988. INIST:7127371. PMID 2832600.

- ↑ "Anti-malarial drugs: possible mechanisms of action in autoimmune disease and prospects for drug development". Lupus 5 (1 Suppl): S4-10. June 1996. doi:10.1177/0961203396005001031. PMID 8803903.

- ↑ Medical Pharmacology and Therapeutics (2nd ed.). p. 370.

- ↑ "The basis of antimalarial action: non-weak base effects of chloroquine on acid vesicle pH". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 36 (2): 213–20. March 1987. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.213. PMID 2435182.

- ↑ "Targeting endosomal acidification by chloroquine analogs as a promising strategy for the treatment of emerging viral diseases". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives 5 (1): e00293. February 2017. doi:10.1002/prp2.293. PMID 28596841.

- ↑ "Toll-like receptors". Annual Review of Immunology 21 (1): 335–76. April 2003. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126. PMID 12524386.

- ↑ "Theories on malarial pigment formation and quinoline action". International Journal for Parasitology 32 (13): 1645–53. December 2002. doi:10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00193-5. PMID 12435449.

- ↑ "Antimalarials: construction of molecular hybrids based on chloroquine". Universitas Scientiarum 13 (3): 306–320. September 2008. http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0122-74832008000300010&script=sci_arttext.

- ↑ Saving lives, buying time : economics of malaria drugs in an age of resistance. National Academies Press. 2004. doi:10.17226/11017. ISBN 9780309092180.

- ↑ "The History of Malaria, an Ancient Disease". Centers for Disease Control. 29 July 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/history/index.htm#chloroquine.

- ↑ "The Preparation of 7-Chloro-4-(4-(N-ethyl-N-β-hydroxyethylamino)-1- methylbutylamino)-quinoline and Related Compounds". Journal of the American Chemical Society 72 (4): 1814–1815. 1950. doi:10.1021/ja01160a116.

- ↑ "7-chloro-4-[5-(N-ethyl-N-2-hydroxyethylamino)-2-pentyl] aminoquinoline, its acid addition salts, and method of preparation" US patent 2546658, issued 1951-03-27, assigned to Sterling Drug Inc.

- ↑ "Hydroxychloroquine trade names". https://drugs-about.com/ing/hydroxychloroquine.html.

External links

- "Hydroxychloroquine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/hydroxychloroquine.

|