Physics:Two-body problem in general relativity

| General relativity |

|---|

|

The two-body problem in general relativity (or relativistic two-body problem) is the determination of the motion and gravitational field of two bodies as described by the field equations of general relativity. Solving the Kepler problem is essential to calculate the bending of light by gravity and the motion of a planet orbiting its sun. Solutions are also used to describe the motion of binary stars around each other, and estimate their gradual loss of energy through gravitational radiation.

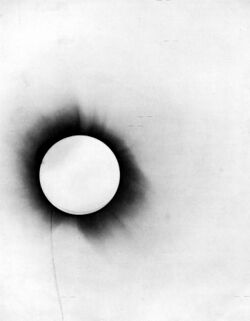

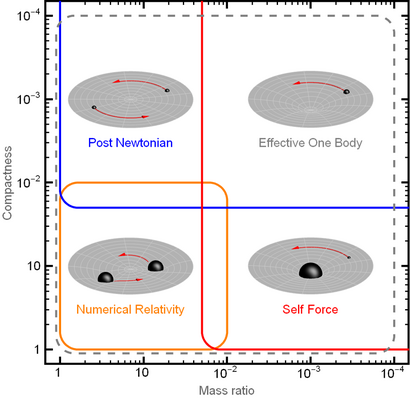

General relativity describes the gravitational field by curved space-time; the field equations governing this curvature are nonlinear and therefore difficult to solve in a closed form. No exact solutions of the Kepler problem have been found, but an approximate solution has: the Schwarzschild solution. This solution pertains when the mass M of one body is overwhelmingly greater than the mass m of the other. If so, the larger mass may be taken as stationary and the sole contributor to the gravitational field. This is a good approximation for a photon passing a star and for a planet orbiting its sun. The motion of the lighter body (called the "particle" below) can then be determined from the Schwarzschild solution; the motion is a geodesic ("shortest path between two points") in the curved space-time. Such geodesic solutions account for the anomalous precession of the planet Mercury, which is a key piece of evidence supporting the theory of general relativity. They also describe the bending of light in a gravitational field, another prediction famously used as evidence for general relativity.

If both masses are considered to contribute to the gravitational field, as in binary stars, the Kepler problem can be solved only approximately. The earliest approximation method to be developed was the post-Newtonian expansion, an iterative method in which an initial solution is gradually corrected. More recently, it has become possible to solve Einstein's field equation using a computer[1][2][3] instead of mathematical formulae. As the two bodies orbit each other, they will emit gravitational radiation; this causes them to lose energy and angular momentum gradually, as illustrated by the binary pulsar PSR B1913+16.

For binary black holes, the numerical solution of the two-body problem was achieved in 2005 after four decades of research when three groups devised breakthrough techniques.[1][2][3]

Historical context

Classical Kepler problem

The Kepler problem derives its name from Johannes Kepler, who worked as an assistant to the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. Brahe took extraordinarily accurate measurements of the motion of the planets of the Solar System. From these measurements, Kepler was able to formulate Kepler's laws, the first modern description of planetary motion:

- The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

- A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

- The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Kepler published the first two laws in 1609 and the third law in 1619. They supplanted earlier models of the Solar System, such as those of Ptolemy and Copernicus. Kepler's laws apply only in the limited case of the two-body problem. Voltaire and Émilie du Châtelet were the first to call them "Kepler's laws".

Nearly a century later, Isaac Newton had formulated his three laws of motion. In particular, Newton's second law states that a force F applied to a mass m produces an acceleration a given by the equation F = ma. Newton then posed the question: what must the force be that produces the elliptical orbits seen by Kepler? His answer came in his law of universal gravitation, which states that the force between a mass M and another mass m is given by the formula where r is the distance between the masses and G is the gravitational constant. Given this force law and his equations of motion, Newton was able to show that two point masses attracting each other would each follow perfectly elliptical orbits. The ratio of sizes of these ellipses is m/M, with the larger mass moving on a smaller ellipse. If M is much larger than m, then the larger mass will appear to be stationary at the focus of the elliptical orbit of the lighter mass m. This model can be applied approximately to the Solar System. Since the mass of the Sun is much larger than those of the planets, the force acting on each planet is principally due to the Sun; the gravity of the planets for each other can be neglected to first approximation.

Apsidal precession

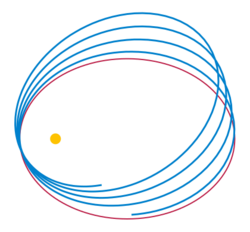

If the potential energy between the two bodies is not exactly the 1/r potential of Newton's gravitational law but differs only slightly, then the ellipse of the orbit gradually rotates (among other possible effects). This apsidal precession is observed for all the planets orbiting the Sun, primarily due to the oblateness of the Sun (it is not perfectly spherical) and the attractions of the other planets to one another. The apsides are the two points of closest and furthest distance of the orbit (the periapsis and apoapsis, respectively); apsidal precession corresponds to the rotation of the line joining the apsides. It also corresponds to the rotation of the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector, which points along the line of apsides.

Newton's law of gravitation soon became accepted because it gave very accurate predictions of the motion of all the planets. These calculations were carried out initially by Pierre-Simon Laplace in the late 18th century, and refined by Félix Tisserand in the later 19th century. Conversely, if Newton's law of gravitation did not predict the apsidal precessions of the planets accurately, it would have to be discarded as a theory of gravitation. Such an anomalous precession was observed in the second half of the 19th century.

Anomalous precession of Mercury

In 1859, Urbain Le Verrier discovered that the orbital precession of the planet Mercury was not quite what it should be; the ellipse of its orbit was rotating (precessing) slightly faster than predicted by the traditional theory of Newtonian gravity, even after all the effects of the other planets had been accounted for.[4] The effect is small (roughly 43 arcseconds of rotation per century), but well above the measurement error (roughly 0.1 arcseconds per century). Le Verrier realized the importance of his discovery immediately, and challenged astronomers and physicists alike to account for it. Several classical explanations were proposed, such as interplanetary dust, unobserved oblateness of the Sun, an undetected moon of Mercury, or a new planet named Vulcan.[5] After these explanations were discounted, some physicists were driven to the more radical hypothesis that Newton's inverse-square law of gravitation was incorrect. For example, some physicists proposed a power law with an exponent that was slightly different from 2.[6]

Others argued that Newton's law should be supplemented with a velocity-dependent potential. However, this implied a conflict with Newtonian celestial dynamics. In his treatise on celestial mechanics, Laplace had shown that if the gravitational influence does not act instantaneously, then the motions of the planets themselves will not exactly conserve momentum (and consequently some of the momentum would have to be ascribed to the mediator of the gravitational interaction, analogous to ascribing momentum to the mediator of the electromagnetic interaction). As seen from a Newtonian point of view, if gravitational influence does propagate at a finite speed, then at all points in time a planet is attracted to a point where the Sun was some time before, and not towards the instantaneous position of the Sun. On the assumption of the classical fundamentals, Laplace had shown that if gravity would propagate at a velocity on the order of the speed of light then the solar system would be unstable, and would not exist for a long time. The observation that the solar system is old enough allowed him to put a lower limit on the speed of gravity that turned out to be many orders of magnitude faster than the speed of light.[5][7]

Laplace's estimate for the speed of gravity is not correct in a field theory which respects the principle of relativity. Since electric and magnetic fields combine, the attraction of a point charge which is moving at a constant velocity is towards the extrapolated instantaneous position, not to the apparent position it seems to occupy when looked at.[note 1] To avoid those problems, between 1870 and 1900 many scientists used the electrodynamic laws of Wilhelm Eduard Weber, Carl Friedrich Gauss, Bernhard Riemann to produce stable orbits and to explain the perihelion shift of Mercury's orbit. In 1890, Maurice Lévy succeeded in doing so by combining the laws of Weber and Riemann, whereby the speed of gravity is equal to the speed of light in his theory. And in another attempt Paul Gerber (1898) even succeeded in deriving the correct formula for the perihelion shift (which was identical to that formula later used by Einstein). However, because the basic laws of Weber and others were wrong (for example, Weber's law was superseded by Maxwell's theory), those hypotheses were rejected.[8] Another attempt by Hendrik Lorentz (1900), who already used Maxwell's theory, produced a perihelion shift which was too low.[5]

Einstein's theory of general relativity

Around 1904–1905, the works of Hendrik Lorentz, Henri Poincaré and finally Albert Einstein's special theory of relativity, exclude the possibility of propagation of any effects faster than the speed of light. It followed that Newton's law of gravitation would have to be replaced with another law, compatible with the principle of relativity, while still obtaining the Newtonian limit for circumstances where relativistic effects are negligible. Such attempts were made by Henri Poincaré (1905), Hermann Minkowski (1907) and Arnold Sommerfeld (1910).[9] In 1907 Einstein came to the conclusion that to achieve this a successor to special relativity was needed. From 1907 to 1915, Einstein worked towards a new theory, using his equivalence principle as a key concept to guide his way. According to this principle, a uniform gravitational field acts equally on everything within it and, therefore, cannot be detected by a free-falling observer. Conversely, all local gravitational effects should be reproducible in a linearly accelerating reference frame, and vice versa. Thus, gravity acts like a fictitious force such as the centrifugal force or the Coriolis force, which result from being in an accelerated reference frame; all fictitious forces are proportional to the inertial mass, just as gravity is. To effect the reconciliation of gravity and special relativity and to incorporate the equivalence principle, something had to be sacrificed; that something was the long-held classical assumption that our space obeys the laws of Euclidean geometry, e.g., that the Pythagorean theorem is true experimentally. Einstein used a more general geometry, pseudo-Riemannian geometry, to allow for the curvature of space and time that was necessary for the reconciliation; after eight years of work (1907–1915), he succeeded in discovering the precise way in which space-time should be curved in order to reproduce the physical laws observed in Nature, particularly gravitation. Gravity is distinct from the fictitious forces centrifugal force and coriolis force in the sense that the curvature of spacetime is regarded as physically real, whereas the fictitious forces are not regarded as forces. The very first solutions of his field equations explained the anomalous precession of Mercury and predicted an unusual bending of light, which was confirmed after his theory was published. These solutions are explained below.

General relativity, special relativity and geometry

In the normal Euclidean geometry, triangles obey the Pythagorean theorem, which states that the square distance ds2 between two points in space is the sum of the squares of its perpendicular components where dx, dy and dz represent the infinitesimal differences between the x, y and z coordinates of two points in a Cartesian coordinate system. Now imagine a world in which this is not quite true; a world where the distance is instead given by where F, G and H are arbitrary functions of position. It is not hard to imagine such a world; we live on one. The surface of the earth is curved, which is why it is impossible to make a perfectly accurate flat map of the earth. Non-Cartesian coordinate systems illustrate this well; for example, in the spherical coordinates (r, θ, φ), the Euclidean distance can be written

Another illustration would be a world in which the rulers used to measure length were untrustworthy, rulers that changed their length with their position and even their orientation. In the most general case, one must allow for cross-terms when calculating the distance ds where the nine functions gxx, gxy, ..., gzz constitute the metric tensor, which defines the geometry of the space in Riemannian geometry. In the spherical-coordinates example above, there are no cross-terms; the only nonzero metric tensor components are grr = 1, gθθ = r2 and gφφ = r2 sin2 θ.

In his special theory of relativity, Albert Einstein showed that the distance ds between two spatial points is not constant, but depends on the motion of the observer. However, there is a measure of separation between two points in space-time — called "proper time" and denoted with the symbol dτ — that is invariant; in other words, it does not depend on the motion of the observer. which may be written in spherical coordinates as

This formula is the natural extension of the Pythagorean theorem and similarly holds only when there is no curvature in space-time. In general relativity, however, space and time may have curvature, so this distance formula must be modified to a more general form just as we generalized the formula to measure distance on the surface of the Earth. The exact form of the metric gμν depends on the gravitating mass, momentum and energy, as described by the Einstein field equations. Einstein developed those field equations to match the then known laws of Nature; however, they predicted never-before-seen phenomena (such as the bending of light by gravity) that were confirmed later.

Geodesic equation

According to Einstein's theory of general relativity, particles of negligible mass travel along geodesics in the space-time. In uncurved space-time, far from a source of gravity, these geodesics correspond to straight lines; however, they may deviate from straight lines when the space-time is curved. The equation for the geodesic lines is[10] where Γ represents the Christoffel symbol and the variable q parametrizes the particle's path through space-time, its so-called world line. The Christoffel symbol depends only on the metric tensor gμν, or rather on how it changes with position. The variable q is a constant multiple of the proper time τ for timelike orbits (which are traveled by massive particles), and is usually taken to be equal to it. For lightlike (or null) orbits (which are traveled by massless particles such as the photon), the proper time is zero and, strictly speaking, cannot be used as the variable q. Nevertheless, lightlike orbits can be derived as the ultrarelativistic limit of timelike orbits, that is, the limit as the particle mass m goes to zero while holding its total energy fixed.

Schwarzschild solution

An exact solution to the Einstein field equations is the Schwarzschild metric, which corresponds to the external gravitational field of a stationary, uncharged, non-rotating, spherically symmetric body of mass M. It is characterized by a length scale rs, known as the Schwarzschild radius, which is defined by the formula where G is the gravitational constant. The classical Newtonian theory of gravity is recovered in the limit as the ratio rs/r goes to zero. In that limit, the metric returns to that defined by special relativity.

In practice, this ratio is almost always extremely small. For example, the Schwarzschild radius rs of the Earth is roughly 9 mm; at the surface of the Earth, the corrections to Newtonian gravity are only one part in a billion. The Schwarzschild radius of the Sun is much larger, roughly 2953 meters, but at its surface, the ratio rs/r is roughly 4 parts in a million. A white dwarf star is much denser, but even here the ratio at its surface is roughly 250 parts in a million. The ratio only becomes large close to ultra-dense objects such as neutron stars (where the ratio is roughly 50%) and black holes.

Orbits about the central mass

The orbits of a test particle of infinitesimal mass about the central mass is given by the equation of motion where is the specific relative angular momentum, and is the reduced mass. This can be converted into an equation for the orbit where, for brevity, two length-scales, and have been introduced. They are constants of the motion and depend on the initial conditions (position and velocity) of the test particle. Hence, the solution of the orbit equation is

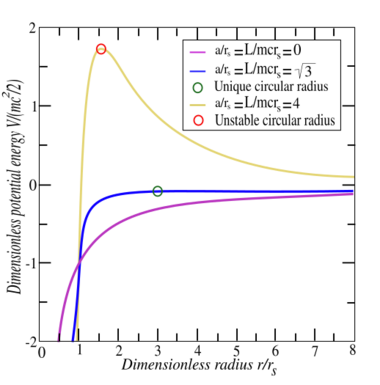

Effective radial potential energy

The equation of motion for the particle derived above can be rewritten using the definition of the Schwarzschild radius rs as which is equivalent to a particle moving in a one-dimensional effective potential The first two terms are well-known classical energies, the first being the attractive Newtonian gravitational potential energy and the second corresponding to the repulsive "centrifugal" potential energy; however, the third term is an attractive energy unique to general relativity. As shown below and elsewhere, this inverse-cubic energy causes elliptical orbits to precess gradually by a small angle δ ω per revolution: where a is the orbital semi-major axis and e is the eccentricity. Here, δω is not the change in the φ-coordinate from the spherical coordinates ( t, r, θ, φ ) but close to it: It's the change in the argument of periapsis of the classical closed orbit.

The third term is attractive and dominates at small r values, giving a critical inner radius rinner at which a particle is drawn inexorably inwards to r = 0 ; this inner radius is a function of the particle's angular momentum per unit mass or, equivalently, the a length-scale defined above.

Circular orbits and their stability

The effective potential V can be re-written in terms of the length

Circular orbits are possible when the effective force is zero: i.e., when the two attractive forces – Newtonian gravity (first term) and the attraction unique to general relativity (third term) – are exactly balanced by the repulsive centrifugal force (second term). There are two radii at which this balancing can occur, denoted here as rinner and router: which are obtained using the quadratic formula. The inner radius rinner is unstable, because the attractive third force strengthens much faster than the other two forces when r becomes small; if the particle slips slightly inwards from rinner (where all three forces are in balance), the third force dominates the other two and draws the particle inexorably inwards to r = 0 . At the outer radius, however, the circular orbits are stable; the third term is less important and the system behaves more like the non-relativistic Kepler problem.

When A is much greater than rs (the classical case), these formulae become approximately

Substituting the definitions of A and rs into router yields the classical formula for a particle of mass m orbiting a body of mass M.

The following equation where ωφ is the orbital angular speed of the particle, is obtained in non-relativistic mechanics by setting the centrifugal force equal to the Newtonian gravitational force: where is the reduced mass.

In our notation, the classical orbital angular speed equals

At the other extreme, when approaches 3 rs2 from above, the two radii converge to a single value The quadratic solutions above ensure that router is always greater than 3 rs , whereas rinner lies between 3 / 2 rs and 3 rs . Circular orbits smaller than 3 / 2 rs are not possible. For massless particles, goes to infinity, implying that there is a circular orbit for photons at rinner = 3 / 2 rs . The sphere of this radius is sometimes known as the photon sphere.

Precession of elliptical orbits

The orbital precession rate may be derived using this radial effective potential V, which includes the non-Newtonian centrifugal force. A small radial deviation from a circular orbit of radius router will oscillate in a stable manner with an angular frequency which equals

Taking the square root of both sides and expanding using the binomial theorem yields the formula Multiplying by the period T of one revolution gives the precession of the orbit per revolution where we have used Ωφ T ≈ 2 π (exact for circular orbits) and the definition of the length-scale set by a. Substituting the definition of the Schwarzschild radius rs gives

This may be simplified using the elliptical orbit's semi-major axis a, eccentricity e, and specific relative angular momentum h, which are related by the formula to give the precession angle

Since the closed classical orbit is generally an ellipse, the quantity a ( 1 − e2) is the semi-latus rectum of the ellipse.

Hence, the final formula of angular apsidal precession for a unit complete revolution is

Beyond the Schwarzschild solution

Post-Newtonian expansion

In the Schwarzschild solution, it is assumed that the larger mass M is stationary and it alone determines the gravitational field (i.e., the geometry of space-time) and, hence, the lesser mass m follows a geodesic path through that fixed space-time. This is a reasonable approximation for photons and the orbit of Mercury, which is roughly 6 million times lighter than the Sun. However, it is inadequate for binary stars, in which the masses may be of similar magnitude.

The metric for the case of two comparable masses cannot be solved in closed form and therefore one has to resort to approximation techniques such as the post-Newtonian approximation or numerical approximations. In passing, we mention one particular exception in lower dimensions (see R = T model for details). In (1+1) dimensions, i.e. a space made of one spatial dimension and one time dimension, the metric for two bodies of equal masses can be solved analytically in terms of the Lambert W function.[11] However, the gravitational energy between the two bodies is exchanged via dilatons rather than gravitons which require three-space in which to propagate.

The post-Newtonian expansion is a calculational method that provides a series of ever more accurate solutions to a given problem.[12] The method is iterative; an initial solution for particle motions is used to calculate the gravitational fields; from these derived fields, new particle motions can be calculated, from which even more accurate estimates of the fields can be computed, and so on. This approach is called "post-Newtonian" because the Newtonian solution for the particle orbits is often used as the initial solution.

The theory can be divided into two parts: first one finds the two-body effective potential that captures the GR corrections to the Newtonian potential. Secondly, one should solve the resulting equations of motion.

Modern computational approaches

Einstein's equations can also be solved on a computer using sophisticated numerical methods.[1][2][3] Given sufficient computer power, such solutions can be more accurate than post-Newtonian solutions. However, such calculations are demanding because the equations must generally be solved in a four-dimensional space. Nevertheless, beginning in the late 1990s, it became possible to solve difficult problems such as the merger of two black holes, which is a very difficult version of the Kepler problem in general relativity.

Gravitational radiation

If there is no incoming gravitational radiation, according to general relativity, two bodies orbiting one another will emit gravitational radiation, causing the orbits to gradually lose energy.

The formulae describing the loss of energy and angular momentum due to gravitational radiation from the two bodies of the Kepler problem have been calculated.[13] The rate of losing energy (averaged over a complete orbit) is given by[14] where e is the orbital eccentricity and a is the semimajor axis of the elliptical orbit. The angular brackets on the left-hand side of the equation represent the averaging over a single orbit. Similarly, the average rate of losing angular momentum equals

The rate of period decrease is given by[13][15] where Pb is orbital period.

The losses in energy and angular momentum increase significantly as the eccentricity approaches one, i.e., as the ellipse of the orbit becomes ever more elongated. The radiation losses also increase significantly with a decreasing size a of the orbit.

-

Experimentally observed changes in the time of the periastron of the binary pulsar PSR B1913+16 (red dots) matches the change due to the reduction in orbital period predicted by general relativity (blue curve) almost exactly.

-

Two neutron stars rotating rapidly around one another gradually lose energy by emitting gravitational radiation. As they lose energy, they orbit each other more quickly and more closely to one another.

See also

- Binet equation

- Center of mass (relativistic)

- Gravitational two-body problem

- Kepler problem

- Newton's theorem of revolving orbits

- Schwarzschild geodesics

Notes

- ↑ Feynman Lectures on Physics vol. II gives a thorough treatment of the analogous problem in electromagnetism. Feynman shows that for a moving charge, the non-radiative field is an attraction/repulsion not toward the apparent position of the particle, but toward the extrapolated position assuming that the particle continues in a straight line in a constant velocity. This is a notable property of the Liénard–Wiechert potentials which are used in the Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory. Presumably the same holds in linearized gravity: e.g., see Gravitoelectromagnetism.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Pretorius, Frans (2005). "Evolution of Binary Black-Hole Spacetimes". Physical Review Letters 95 (12). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.121101. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16197061. Bibcode: 2005PhRvL..95l1101P.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Campanelli, M.; Lousto, C. O.; Marronetti, P.; Zlochower, Y. (2006). "Accurate Evolutions of Orbiting Black-Hole Binaries without Excision". Physical Review Letters 96 (11). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.111101. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16605808. Bibcode: 2006PhRvL..96k1101C.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Baker, John G.; Centrella, Joan; Choi, Dae-Il; Koppitz, Michael; van Meter, James (2006). "Gravitational-Wave Extraction from an Inspiraling Configuration of Merging Black Holes". Physical Review Letters 96 (11). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.111102. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 16605809. Bibcode: 2006PhRvL..96k1102B.

- ↑ Le Verrier, UJJ (1859). "Lettre de M. Le Verrier à M. Faye sur la théorie de Mercure et sur le mouvement du périhélie de cette planète". Comptes Rendus 49: 379–383.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Pais 1982, pp. 253–256.

- ↑ Pais 1982, p. 254.

- ↑ Kopeikin, Efroimsky & Kaplan 2011, p. 177.

- ↑ Roseveare 1982, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Walter 2007, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Weinberg 1972, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Ohta, T.; Mann, R. B. (1997). "Exact solution for the metric and the motion of two bodies in (1+1)-dimensional gravity". Phys. Rev. D 55 (8): 4723–4747. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.55.4723. Bibcode: 1997PhRvD..55.4723M.

- ↑ Kopeikin, Efroimsky & Kaplan 2011, p. [page needed].

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Gravitational Radiation from Point Masses in a Keplerian Orbit". Physical Review 131 (1): 435–440. 1963. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.131.435. Bibcode: 1963PhRv..131..435P.

- ↑ Landau & Lifshitz 1975, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ Weisberg, J.M.; Taylor, J.H. (July 2005). "The Relativistic Binary Pulsar B1913+16: Thirty Years of Observations and Analysis". 328. San Francisco: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. p. 25. Bibcode: 2005ASPC..328...25W. http://aspbooks.org/custom/publications/paper/328-0025.html.

Bibliography

- Adler, R; Bazin M; Schiffer M (1965). Introduction to General Relativity. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 177–193. ISBN 978-0-07-000420-7. https://archive.org/details/introductiontoge0000adle.

- Einstein, A (1956). The Meaning of Relativity (5th ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 92–97. ISBN 978-0-691-02352-6.

- Hagihara, Y (1931). "Theory of the relativistic trajectories in a gravitational field of Schwarzschild". Japanese Journal of Astronomy and Geophysics 8: 67–176. ISSN 0368-346X. Bibcode: 1931AOTok..31...67H.

- Kopeikin, Sergei; Efroimsky, Michael; Kaplan, George (25 October 2011). Relativistic Celestial Mechanics of the Solar System. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-63457-6.

- Lanczos, C (1986). The Variational Principles of Mechanics (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 330–338. ISBN 978-0-486-65067-8.

- Landau, LD; Lifshitz, EM (1975). The Classical Theory of Fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. 2 (revised 4th English ed.). New York: Pergamon Press. pp. 299–309. ISBN 978-0-08-018176-9.

- Misner, CW; Thorne, K; Wheeler, JA (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. pp. Chapter 25 (pp. 636–687), §33.5 (pp. 897–901), and §40.5 (pp. 1110–1116). ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0. (See Gravitation (book).)

- Pais, A. (1982). Subtle is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. Oxford University Press. pp. 253–256. ISBN 0-19-520438-7. https://archive.org/details/subtleislordscie00pais.

- Pauli, W (1958). Theory of Relativity. Translated by G. Field. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 40–41, 166–169. ISBN 978-0-486-64152-2.

- Rindler, W (1977). Essential Relativity: Special, General, and Cosmological (revised 2nd ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. pp. 143–149. ISBN 978-0-387-10090-6.

- Roseveare, N. T. (1982). Mercury's perihelion, from Leverrier to Einstein. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 0-19-858174-2. https://archive.org/details/mercurysperiheli0000rose.

- Synge, JL (1960). Relativity: The General Theory. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing. pp. 289–298. ISBN 978-0-7204-0066-3.

- Wald, RM (1984). General Relativity. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 136–146. ISBN 978-0-226-87032-8. https://archive.org/details/generalrelativit0000wald.

- Walter, S. (2007). "Breaking in the 4-vectors: the four-dimensional movement in gravitation, 1905–1910". in Renn, J.. The Genesis of General Relativity. 3. Berlin: Springer. pp. 193–252. http://www.univ-nancy2.fr/DepPhilo/walter/. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- Weinberg, S (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology. New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 185–201. ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5. https://archive.org/details/gravitationcosmo00stev_0/page/185.

- Whittaker, ET (1937). A Treatise on the Analytical Dynamics of Particles and Rigid Bodies, with an Introduction to the Problem of Three Bodies (4th ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 389–393. ISBN 978-1-114-28944-4.

External links

- Animation showing relativistic precession of stars around the Milky Way supermassive black hole

- Excerpt from Reflections on Relativity by Kevin Brown.

|