Biography:Rainer Weiss

Rainer Weiss | |

|---|---|

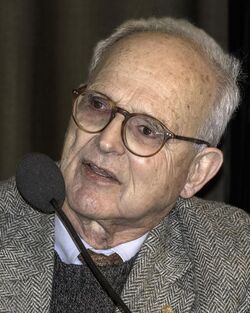

Weiss in 2017 | |

| Born | September 29, 1932 Berlin, Germany |

| Died | August 25, 2025 (aged 92) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Pioneering laser interferometric gravitational wave observation |

| Spouse(s) | Rebecca Young (m. 1959) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics Laser physics Experimental gravitation Cosmic background measurements |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Stark Effect and Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Fluoride (1962) |

| Doctoral advisor | Jerrold R. Zacharias |

| Doctoral students | Nergis Mavalvala Philip K. Chapman Rana X. Adhikari |

| Other notable students | Bruce Allen Sarah Veatch |

Rainer Weiss (/waɪs/ WYSSE, de; September 29, 1932 – August 25, 2025) was a German-American physicist, known for his contributions in gravitational physics and astrophysics. He was a professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an adjunct professor at Louisiana State University. He is best known for inventing the laser interferometric technique which is the basic operation of LIGO. He was Chair of the COBE Science Working Group.[1][2][3]

In 2017, Weiss was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, along with Kip Thorne and Barry Barish, "for decisive contributions to the LIGO detector and the observation of gravitational waves".[4][5][6][7]

Weiss helped realize a number of challenging experimental tests of fundamental physics. He was a member of the Fermilab Holometer experiment, which uses a 40m laser interferometer to measure properties of space and time at quantum scale and provide Planck-precision tests of quantum holographic fluctuation.[8][9]

Early life and education

Rainer Weiss was born in Berlin, Brandenburg, Prussia, Germany, on September 29, 1932, the son of Gertrude Loesner and Frederick A. Weiss.[10][11][12] His father, a physician, neurologist, and psychoanalyst, was forced out of Germany by Nazis because he was Jewish and an active member of the Communist Party. His mother, an actress, was Christian.[13] His aunt was the sociologist Hilda Weiss.[citation needed] His younger sister is playwright Sybille Pearson.[10]

The family fled first to Prague, but Germany's occupation of Czechoslovakia after the 1938 Munich Agreement caused them to flee again; the philanthropic Stix family of St. Louis helped them obtain visas to enter the United States.[14] Weiss spent his youth in New York City, where he attended Columbia Grammar School.[10]

He studied at MIT, dropping out at the beginning of his junior year[15] with the excuse that he had abandoned his coursework to pursue a romantic relationship with a music student from Chicago.[16] While this affair was a contributing factor, Weiss's concurrent vacillation between MIT's engineering and physics tracks may also have played a significant role. Jerrold Zacharias, then an influential physicist and MIT professor, intervened, and Weiss, after working as a technician in Zacharias's lab, eventually returned to receive his S.B. degree in 1955. He would complete his PhD in 1962, still with Zacharias as advisor/mentor.[17][16]

Career

Weiss taught at Tufts University from 1960 to 1962, was a postdoctoral scholar at Princeton University from 1962 to 1964, and then joined the faculty at MIT in 1964.[11]

For Weiss's initial work at MIT, he started a group studying cosmology and gravitation. Needing to develop new technology, particularly in regards to the stabilization of equipment set to measure minute fluctuations, his lab included machine and electronics shop, with a hands-on expectation of his students for fabrication and design.[16]

By 1966, Weiss's tenure at MIT was at risk because of the failure of his group to produce publications. On advice from Bernard Burke, then head of the division on astrophysics in the Physics Department, Weiss recalibrated his standards for submitting articles for publication, eventually finding grounds for publication that he believed met his personal standards as scientifically worthy and publishable. He was then able to qualify for tenure and remain at MIT.[16]

That same year Joseph Weber claimed to have invented a way to detect gravitational waves.[18] When Weiss’s students asked him about Weber’s work, he was unable to explain it to them, as it seemed to contradict his understanding of general relativity. In 1967, to illustrate the principle of gravitational wave detection in a simpler way, Weiss devised a thought experiment involving time of flight measurements of light between free masses in space, which in principle required “impossibly precise clocks”. About a year later, as Weber’s claims remained unconfirmed, Weiss started to realize that maybe Weber was wrong. He eventually revisited his idea and replaced the clocks with laser interferometry and concluded that such an approach could realistically detect gravitational waves, at sensitivities beyond what Weber’s resonant bars could achieve.[19]

Vietnam Era cuts to science grants

In 1973, Weiss was forced to pivot with his work as the US military cut funding for any science that was not determined to be "directly relevant to its core mission." Weiss wrote a proposal to the NSF that described "a new way to measure gravitational waves." This was the work that would eventually lead to his 2017 Nobel Prize, though it was many years before the interferometers Weiss and his students built were sensitive enough to actually detect gravitational waves, making for numerous unpleasant doctoral thesis defenses where Weiss's graduate students were unable to present positive (in layman's terms: any) results.[16]

MIT/Caltech collaboration

Weiss proposed the concept of LIGO to Kip Thorne in 1972, but it took three years before Thorne was convinced it could work.[20] After the study of prototypes at MIT, Caltech, Garching, and Glasgow, and Weiss's estimates what it would take to build a full scale interferometer, Caltech and MIT signed an agreement about the design and construction of LIGO in 1984, with joint leadership by Ronald Drever, Weiss, and Thorne.[21]

In a 2022 interview given to Federal University of Pará in Brazil, Weiss talks about his life and career, the memories of his childhood and youth, his undergraduate and graduate studies at MIT, and the future of gravitational waves astronomy.[22]

Achievements

Weiss brought two fields of fundamental physics research from birth to maturity: characterization of the cosmic background radiation,[3] and interferometric gravitational wave observation.

In 1973 he made pioneering measurements of the spectrum of the cosmic microwave background radiation, taken from a weather balloon, showing that the microwave background exhibited the thermal spectrum characteristic of the remnant radiation from the Big Bang.[15] He later became co-founder and science advisor of the NASA Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) satellite,[1] which made detailed mapping of the radiation.

Weiss also pioneered the concept of using lasers for an interferometric gravitational wave detector, suggesting that the path length required for such a detector would necessitate kilometer-scale arms. He built a prototype in the 1970s, following earlier work by Robert L. Forward.[23][24] He co-founded the NSF LIGO (gravitational-wave detection) project,[25] which was based on his report "A study of a long Baseline Gravitational Wave Antenna System".[26]

Both of these efforts couple challenges in instrument science with physics important to the understanding of the Universe.[27]

In February 2016, he was one of the four scientists of the LIGO/Virgo collaboration presenting at the press conference for the announcement that the first direct gravitational wave observation had been made in September 2015.[28][29][30][31][lower-alpha 1]

Kip Thorne described Weiss as "by a large margin, the most influential person this field [the study of gravitational waves] has seen."[32]

Personal life and death

Classical music was a profound influence and shaping force in Weiss's life, from his early youth in an immigrant family,[clarification needed] through his shared love of Beethoven's Spring Sonata, which cemented his deep personal relationship with mentor Jerrold Zacharias.[16]

He married and had his first child while still in graduate school, "the best time of my life." He was married to Rebecca Young from 1959 until his death, and they had two children.[10]

Weiss died at a hospital in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on August 25, 2025, at the age of 92.[10]

Honors and awards

Weiss has been recognized by numerous awards including:

- In 2006, with John C. Mather, he and the COBE team received the Gruber Prize in Cosmology.[2]

- In 2007, with Ronald Drever, he was awarded the APS Einstein Prize for his work.[33]

- In 2016 and 2017, for the achievement of gravitational waves detection, he received:

- The Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics,[34]

- Gruber Prize in Cosmology,[35]

- Shaw Prize,[36]

- Kavli Prize in Astrophysics[37]

- The Harvey Prize together with Kip Thorne and Ronald Drever.[38]

- The Smithsonian magazine's American Ingenuity Award in the Physical Science category, with Kip Thorne and Barry Barish.[39]

- The Willis E. Lamb Award for Laser Science and Quantum Optics, 2017.[40]

- Princess of Asturias Award (2017) (jointly with Kip Thorne and Barry Barish).[41]

- The Nobel Prize in Physics (2017) (jointly with Kip Thorne and Barry Barish)[4]

- Fellowship of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters[42]

- In 2018, he was awarded the American Astronomical Society's Joseph Weber Award for Astronomical Instrumentation "for his invention of the interferometric gravitational-wave detector, which led to the first detection of long-predicted gravitational waves."[43]

- In 2020 he was elected a Legacy Fellow of the American Astronomical Society.[44]

Selected publications

- Weiss, R.; Stroke, H.H.; Jaccarino, V.; Edmonds, D.S. (1957). "Magnetic Moments and Hyperfine Structures Anomalies of Cs133, Cs135 and Cs137". Phys. Rev. 105 (2): 590–603. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.590. Bibcode: 1957PhRv..105..590S.

- R. Weiss (1961). "Molecular Beam Electron Bombardment Detector". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 32 (4): 397–401. doi:10.1063/1.1717386. Bibcode: 1961RScI...32..397W.

- R. Weiss; L. Grodzins (1962). "A Search for a Frequency Shift of 14.4 keV Photons on Traversing Radiation Fields". Physics Letters 1 (8): 342. doi:10.1016/0031-9163(62)90420-1. Bibcode: 1962PhL.....1..342W.

- Weiss, Rainer (1963). "Stark Effect and Hyperfine Structure of Hydrogen Fluoride". Phys. Rev. 131 (2): 659–665. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.131.659. Bibcode: 1963PhRv..131..659W.

- R. Weiss; B. Block (1965). "A Gravimeter to Monitor the OSO Dilational Model of the Earth". J. Geophys. Res. 70 (22): 5615. doi:10.1029/JZ070i022p05615. Bibcode: 1965JGR....70.5615W.

- R. Weiss; G. Blum (1967). "Experimental Test of the Freundlich Red-Shift Hypothesis". Phys. Rev. 155 (5): 1412. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.155.1412. Bibcode: 1967PhRv..155.1412B.

- R. Weiss (1967). "Electric and Magnetic Field Probes". Am. J. Phys. 35 (11): 1047–1048. doi:10.1119/1.1973723. Bibcode: 1967AmJPh..35.1047W.

- R.Weiss and S. Ezekiel (1968). "Laser-Induced Fluorescence in a Molecular Beam of Iodine". Phys. Rev. Lett. 20 (3): 91–93. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.20.91. Bibcode: 1968PhRvL..20...91E.

- R. Weiss; D. Muehlner (1970). "A Measurement of the Isotropic Background Radiation in the Far Infrared". Phys. Rev. Lett. 24 (13): 742. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.24.742. Bibcode: 1970PhRvL..24..742M.

- R. Weiss (1972). "Electromagnetically Coupled Broadband Gravitational Antenna". Quarterly Progress Report, Research Laboratory of Electronics, MIT 105: 54. https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/56271/RLE_QPR_105_V.pdf?sequence=1#page=38. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- R. Weiss; D. Muehlner (1973). "Balloon Measurements of the Far Infrared Background Radiation". Phys. Rev. D 7 (2): 326. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.7.326. Bibcode: 1973PhRvD...7..326M.

- R. Weiss; D. Muehlner (1973). "Further Measurements of the Submillimeter Background at Balloon Altitude". Phys. Rev. Lett. 30 (16): 757. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.30.757. Bibcode: 1973PhRvL..30..757M.

- R. Weiss; D.K. Owens (1974). "Measurements of the Phase Fluctuations on a He-Ne Zeeman Laser". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 45 (9): 1060. doi:10.1063/1.1686809. Bibcode: 1974RScI...45.1060O.

- R. Weiss, D.K. Owens; D. Muehlner (1979). "A Large Beam Sky Survey at Millimeter and Submillimeter Wavelengths Made from Balloon Altitudes". Astrophysical Journal 231: 702. doi:10.1086/157235. Bibcode: 1979ApJ...231..702O.

- Weiss, R.; Downey, P.M.; Bachner, F.J.; Donnelly, J.P.; Lindley, W.T.; Mountain, R.W.; Silversmith, D.J. (1980). "Monolithic Silicon Bolometers". Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves 1 (6): 910. doi:10.1364/ao.23.000910. PMID 18204660.

- R. Weiss (1980). "Measurements of the Cosmic Background Radiation". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 18: 489–535. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.18.090180.002421. Bibcode: 1980ARA&A..18..489W.

- R. Weiss (1980). "The COBE Project". Physica Scripta 21 (5): 670. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/21/5/016. Bibcode: 1980PhyS...21..670W.

- R. Weiss, S.S. Meyer; A.D. Jeffries (1983). "A Search for the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich Effect at Millimeter Wavelengths". Astrophys. J. Lett. 271: L1. doi:10.1086/184080. Bibcode: 1983ApJ...271L...1M.

- Weiss, R.; Halpern, M.; Benford, R.; Meyer, S.; Muehlner, D. (1988). "Measurements of the Anisotropy of the Cosmic Background Radiation and Diffuse Galactic Emission at Millimeter and Submillimeter Wavelengths". Astrophys. J. 332: 596. doi:10.1086/166679. Bibcode: 1988ApJ...332..596H.

- Mather, J. C.; Cheng, E. S.; Eplee, R. E. (Jr.); Isaacman, R. B.; Meyer, S. S.; Shafer, R. A.; Weiss, R.; Wright, E. L. et al. (1990). "A Preliminary Measurement of the Cosmic Microwave Background Spectrum by the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE) Satellite". Astrophys. J. 354: L37. doi:10.1086/185717. Bibcode: 1990ApJ...354L..37M.

- Smoot, G.; Bennett, C.; Weber, R.; Maruschak, J.; Ratliff, R.; Janssen, M.; Chitwood, J. et al. (1990). "COBE Differential Microwave Radiometers: Instrument Design and Implementation". Astrophys. J. 360: 685. doi:10.1086/169154. Bibcode: 1990ApJ...360..685S.

- R. Weiss (1990). "Interferometric Gravitational Wave Detectors". Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on General Relativity and Gravitation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 331. ISBN 9780521384285. https://archive.org/details/generalrelativit00ashb.

- Shoemaker, David; Fritschel, Peter; Giaime, Joseph; Christensen, Nelson; Weiss, Rainer (1991). "Prototype Michelson Interferometer with Fabry-Perot Cavities". Applied Optics 30 (22): 3133–8. doi:10.1364/AO.30.003133. PMID 20706365. Bibcode: 1991ApOpt..30.3133S.

Notes

- ↑ Other physicists presenting were Gabriela González, David Reitze, Kip Thorne, and France A. Córdova from the NSF.

See also

- List of Jewish Nobel laureates

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lars Brink (June 2, 2014). Nobel Lectures in Physics (2006–2010). World Scientific. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-981-4612-70-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=yRS3CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA25.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "NASA and COBE Scientists Win Top Cosmology Prize". NASA. 2006. http://www.nasa.gov/centers/goddard/news/topstory/2006/gruber_award.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weiss, Rainer (1980). "Measurements of the Cosmic Background Radiation". Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 18: 489–535. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.18.090180.002421. Bibcode: 1980ARA&A..18..489W. http://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/level5/March03/Weiss/Weiss5.html. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2017". The Nobel Foundation. October 3, 2017. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2017/press.html.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul; Amos, Jonathan (October 3, 2017). "Einstein's waves win Nobel Prize". BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-41476648.

- ↑ Overbye, Dennis (October 3, 2017). "2017 Nobel Prize in Physics Awarded to LIGO Black Hole Researchers". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/03/science/nobel-prize-physics.html.

- ↑ Kaiser, David (October 3, 2017). "Learning from Gravitational Waves". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/03/opinion/gravitational-waves-ligo-funding.html.

- ↑ Emily Tapp (October 6, 2017). "Why we built the Holometer". IOP, Classical and Quantum Gravity journal. https://cqgplus.com/2017/10/06/why-we-built-the-holometer/.

- ↑ Aaron Chou (2017). "The Holometer: an instrument to probe Planckian quantum geometry". Class. Quantum Grav. 34 (6): 065005. doi:10.1088/1361-6382/aa5e5c. Bibcode: 2017CQGra..34f5005C.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 McCain, Dylan Loeb (August 26, 2025). "Rainer Weiss, Who Gave a Nod to Einstein and the Big Bang, Dies at 92". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/26/science/rainer-weiss-dead.html. Retrieved August 26, 2025.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Weiss CV at mit.edu". http://emvogil-3.mit.edu/~weiss/rw/rwbiog.pdf.

- ↑ "MIT physicist Rainer Weiss shares Nobel Prize in physics". MIT News. October 3, 2017. https://news.mit.edu/2017/mit-physicist-rainer-weiss-shares-nobel-prize-physics-1003.

- ↑ "Rainer Weiss Biography". kavliprize.org. http://www.kavliprize.org/sites/default/files/Rainer%20Weiss%20autobiography.pdf.

- ↑ Shirley K. Cohen (May 10, 2000). "Interview with Rainer Weiss". Oral History Project, California Institute of Technology. http://oralhistories.library.caltech.edu/183/1/Weiss_OHO.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cho, Adrian (August 4, 2016). "Meet the College Dropout who Invented the Gravitational Wave Detector ", Science. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Goodman, Daniel (2019). "Find Your Path: Unconventional Lessons from 36 Leading Scientists and Engineers" (in en-US). pp. 239–51. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262537544/find-your-path/.

- ↑ Weiss, Rainer (1962). Stark effect and hyperfine structure of hydrogen fluoride (Ph.D.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. OCLC 33374441. ProQuest 302113994. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ↑ The freest of free-falls | NASA Blueshift

- ↑ Q&A: Rainer Weiss on LIGO’s origins

- ↑ Ten Years Later, LIGO is a Black-Hole Hunting Machine

- ↑ A Brief History of LIGO

- ↑ Interview with Rainer Weiss (2017 Physics Nobel Prize Laureate). Federal University of Pará. 2022.

- ↑ Cho, Adrian (October 3, 2017). "Ripples in space: U.S. trio wins physics Nobel for discovery of gravitational waves ," Science. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ↑ Cervantes-Cota, Jorge L., Galindo-Uribarri, Salvador, and Smoot, George F. (2016). "A Brief History of Gravitational Waves," Universe, 2, no. 3, 22. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ↑ Mervis, Jeffrey. "Got gravitational waves? Thank NSF's approach to building big facilities". Science Magazine. ISSN 1095-9203. https://www.science.org/content/article/got-gravitational-waves-thank-nsf-s-approach-building-big-facilities.

- ↑ Linsay, P., Saulson, P., and Weiss, R. (1983). "A Study of a Long Baseline Gravitational Wave Antenna System , NSF. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ↑ David Shoemaker (2012). "The Evolution of Advanced LIGO". LIGO Magazine (1). http://www.ligo.org/magazine/LIGO-magazine-issue-1.pdf#page=8. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ Twilley, Nicola. "Gravitational Waves Exist: The Inside Story of How Scientists Finally Found Them". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/gravitational-waves-exist-heres-how-scientists-finally-found-them.

- ↑ Abbott, B.P. (2016). "Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger". Phys. Rev. Lett. 116 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.061102. PMID 26918975. Bibcode: 2016PhRvL.116f1102A.

- ↑ Naeye, Robert (February 11, 2016). "Gravitational Wave Detection Heralds New Era of Science". Sky and Telescope. http://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/gravitational-wave-detection-heralds-new-era-of-science-0211201644/.

- ↑ Castelvecchi, Davide; Witze, Alexandra (February 11, 2016). "Einstein's gravitational waves found at last". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19361. http://www.nature.com/news/einstein-s-gravitational-waves-found-at-last-1.19361. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Rainer Weiss, Nobel Prize-winner who helped unlock secrets of the universe, dies at 92 - The Boston Globe" (in en-US). https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/08/31/metro/mit-nobel-prize-winner-rainer-weiss-passes-away/.

- ↑ "Prize Recipient". aps.org. http://www.aps.org/programs/honors/prizes/prizerecipient.cfm?last_nm=Weiss&first_nm=Rainer&year=2007.

- ↑ "Breakthrough Prize – Special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics Awarded For Detection of Gravitational Waves 100 Years After Albert Einstein Predicted Their Existence" (in en). San Francisco. May 2, 2016. https://breakthroughprize.org/News/32.

- ↑ "2016 Gruber Cosmology Prize Press Release" (in en). The Gruber Foundation. May 4, 2016. http://gruber.yale.edu/cosmology/press/2016-gruber-cosmology-prize-press-release.

- ↑ "Shaw Prize 2016". http://www.shawprize.org/en/shaw.php?tmp=3&twoid=102&threeid=254&fourid=476.

- ↑ Prize, The Kavli. "9 Scientific Pioneers Receive The 2016 Kavli Prizes". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ↑ "Harvey Prize 2016". https://harveypz.net.technion.ac.il/harvey-prize-laureates/.

- ↑ "Meet the Team of Scientists Who Discovered Gravitational Waves". http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/wave-catchers-ligo-team-winner-smithsonian-ingenuity-awards-2016-physical-sciences-180961124/.

- ↑ "The Willis E. Lamb Award for Laser Science and Quantum Optics". http://lambaward.org/.

- ↑ "The Princess of Asturias Foundation". https://www.fpa.es/en/error404.do.

- ↑ "Group 2: Astronomy, Physics and Geophysics". Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters. http://english.dnva.no/c40134/artikkel/vis.html?tid=40149.

- ↑ "Joseph Weber Award for Astronomical Instrumentation". American Astronomical Society. https://aas.org/grants-and-prizes/joseph-weber-award-astronomical-instrumentation.

- ↑ "AAS Fellows". AAS. https://aas.org/grants-and-prizes/aas-fellows.

Further reading

- Cho, A. (August 5, 2016). "The storyteller". Science 353 (6299): 532–537. doi:10.1126/science.353.6299.532. PMID 27493164.

- Mather, J.; Boslough, J. (2008). The very first light: The true inside story of the scientific journey back to the dawn of the universe. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01576-4. https://archive.org/details/veryfirstlight00john.

- Bartusiak, M. (2000). Einstein's unfinished symphony: Listening to the sounds of space-time. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-425-18620-6. https://archive.org/details/einsteinsunfinis00bart_0.

External links

- Rainer Weiss on IMDb

- Rainer Weiss's website at MIT

- LIGO Group at the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research

- Rainer Weiss at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Q&A: Rainer Weiss on LIGO's origins at news.mit.edu

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine{{cbignore} b|title=UW Frontiers of Physics Lecture: Dr. Rainer Weiss, Fall 2016, recorded October 25, U. Washington College of Arts & Sciences|website=YouTube|date=November 10, 2016|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTqTx1gX1wY}} * Miss nobel-id as parameter including the Nobel Lecture 8 December 2017 LIGO and Gravitational Waves I

|