Biology:Parakaryon myojinensis

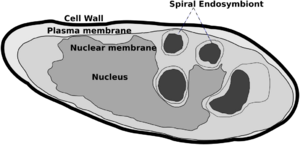

Drawing showing unique cell structure with cell wall, single nuclear membrane, and a single large spiral endosymbiont (seen in section), a combination found neither in prokaryotes nor eukaryotes. Cell is 10 μm long. | |

| Scientific classification | |

|---|---|

| Higher classification: | incertae sedis |

| Genus: | Parakaryon Yamaguchi et al. 2012[1] |

| Species: | P. myojinensis Yamaguchi et al. 2012[1] |

Parakaryon myojinensis, also known as the Myojin parakaryote, is a highly unusual species of single-celled organism known only from a single specimen, described in 2012. It has features of both prokaryotes and eukaryotes but is apparently distinct from either group, making it unique among organisms discovered thus far.[1] It is the sole species in the genus Parakaryon.

Etymology

The generic name Parakaryon comes from Greek παρά (pará, "beside", "beyond", "near") and κάρυον (káryon, "nut", "kernel", "nucleus"), and reflects its distinction from eukaryotes and prokaryotes. The specific name myojinensis reflects the locality where the only sample was collected: from the bristle of a scale worm collected from hydrothermal vents at Myōjin Knoll (明神海丘,[2] [ ⚑ ] 32°06.2′N 139°52.1′E / 32.1033°N 139.8683°E), about 1,240 metres (4,070 ft) deep in the Pacific Ocean, near Aogashima island, southeast of the Japanese archipelago. The authors explain the full binomial as "next to (eu)karyote from Myojin".[1]

Structure

Parakaryon myojinensis has some structural features unique to eukaryotes, some features unique to prokaryotes, and some features different to both. The table below details these structures, with matching traits coloured beige.[1][3]

| Structure | Prokaryotes | Eukaryotes | Parakaryon myojinensis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus present | No | Yes | Yes |

| No. of nuclear membrane layers | N/A | 2 | 1 |

| Nuclear pores present | N/A | Yes | No |

| Ribosome location | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic and intranuclear |

| Endosymbionts present | No | Yes | Yes |

| Endoplasmic reticulum present | No | Yes | No |

| Golgi apparatus present | No | Yes | No |

| Mitochondria present | No | Usually | No |

| Chromosome structure | Variable | Linear | Filamentous |

| Cytoskeleton present | Yes | Yes | No |

Yamaguchi et al proposed in their 2012 paper[1] that there were three reasons why the single frozen specimen they named Parakaryon myojinensis was not simply a result of parasitic or predatory bacteria living within another prokaryote host - which they acknowledged is known from several examples:

- "It is difficult to imagine that multiple bacteria of different species attacked a host at the same time." They referred to Figure 2d, showing the isolated forms of the inclusions, one large helix with three turns (volume 2.3 μm³) and two much smaller pieces (volumes 0.2 & 0.1 μm³).

- "Secondly, because the cytoplasms of the host and the endosymbionts show orderly and electron-dense cellular structures, no digestion in either host or endosymbionts appears to have occurred."

- "Lastly, if P. myojinensis originated due to a current interaction between predators and hosts, then there must be dense populations of predators and hosts, because predators need to find hosts quickly for survival once they are released from the previous host."[1]

Another paper with Masashi Yamaguchi as the lead author was published in 2016. Detailing the discovery of helical bacteria on polychaetes collected from the same location on Myojin Knoll, they named them "Myojin spiral bacteria".[4] In 2020, Yamaguchi and two others published a new short paper on their studies of the microbiota of polychaetes from Myojin Knoll. The authors stated "Among them, we often observed bacteria that contained intracellular bacteria on ultrathin sections." They studied one such specimen and concluded that the "host" bacterium was dead and its cell wall broken. The smaller bacteria could have been feeding on the larger bacterium but they also suggest "The association of the bacteria with dead bacteria could also have been artificially caused by the centrifugation steps used for the preparation of specimens for electron microscopy." In this paper, all five mentions of Parakaryon myojinensis were as a valid taxon without any doubt implied.[5]

Classification

It is not clear whether P. myojinensis can or should be classified as a eukaryote or a prokaryote, the two categories to which all other cellular life belongs. Excluding viruses, which are non-cellular and often distinguished from cellular life, and excluding several fossils that contain disputed evidence of ancient life (nanobacteria, nanobes), P. myojinensis is the only organism to have a completely unknown position in the tree of life.[citation needed] Adding to the difficulties of classification, only one instance of this organism has been discovered to date, and so scientists have been unable to study it further.[1]

British evolutionary biochemist Nick Lane hypothesized in a 2015 book that the existence of P. myojinensis may be an important clue to the origins of life on Earth, perhaps as an example of the abiogenesis of simple organisms from organic compounds continuing in the present day. The fact that P. myojinensis was discovered near hydrothermal vents, which have been proposed as possible primordial reaction chambers for the earliest ancestors of prokaryotes and eukaryotes, lends credence to this idea.[6]

See also

- Anatoma fujikurai, a species of gastropod discovered at the same location

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 "Prokaryote or eukaryote? A unique microorganism from the deep sea.". J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 61 (6): 423–431. 2012. doi:10.1093/jmicro/dfs062. PMID 23024290.

- ↑ Fumitoshi, Murakami (1997). "Fumitoshi MURAKAMI, The Forming Mechanism of the Submarine Caldera on Myojin Knoll in the Northern Part of the Izu-Ogasawara (Bonin) Arc". Journal of Geography (Chigaku Zasshi) 106 (1): 70–86. doi:10.5026/jgeography.106.70. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10002234999/en.

- ↑ Evolution of complex life on Earth, take 2

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Masashi; Yamada, Hiroyuki; Higuchi, Kimitaka; Yamamoto, Yuta; Arai, Shigeo; Murata, Kazuyoshi; Mori, Yuko; Furukawa, Hiromitsu et al. (2016). "High-voltage electron microscopy tomography and structome analysis of unique spiral bacteria from the deep sea". Microscopy 65 (4): 363–369. doi:10.1093/jmicro/dfw016. https://www.academia.edu/download/84596997/eee6e7177b7a9f2d5f7704bb2a2f3ed0a8ce.pdf. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Masashi; Yamada, Hiroyuki; Chibana, Hiroki (2020). "Deep-Sea Bacteria Harboring Bacterial Endosymbionts in a Cytoplasm?: 3D Electron Microscopy by Serial Ultrathin Sectioning of Freeze-Substituted Specimen". Cytologia 85 (3): 209–211. doi:10.1508/cytologia.85.20. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345449815. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ Nick Lane (2015). "Epilogue: From the Deep". The Vital Question: Energy, Evolution, and the Origins of Complex Life. W.W.Norton and Company. pp. 281–290. ISBN 978-0-393-08881-6.

Further reading

- Yamaguchi, Masashi; Yamada, Hiroyuki; Uematsu, Katsuyuki; Horinouchi, Yusuke; Chibana, Hiroji (2018-09-25). "Electron Microscopy and Structome Analysis of Unique Amorphous Bacteria from the Deep Sea in Japan". Cytologia 83 (3): 336–341. doi:10.1508/cytologia.83.337.

|