Chemistry:Dimethyl ether

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

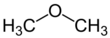

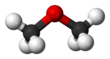

| Preferred IUPAC name

Methoxymethane[1] | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| Abbreviations | DME | ||

| 1730743 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Dimethyl+ether | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1033 | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2H6O | |||

| Molar mass | 46.069 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Ethereal[2] | ||

| Density | 2.1146 kg m−3 (gas, 0 °C, 1013 mbar)[2] 0.735 g/mL (liquid, −25 °C)[2] | ||

| Melting point | −141 °C; −222 °F; 132 K | ||

| Boiling point | −24 °C; −11 °F; 249 K | ||

| 71 g/L (at 20 °C (68 °F)) | |||

| log P | 0.022 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 592.8 kPa[3] | ||

| −26.3×10−6 cm3 mol−1 | |||

| 1.30 D | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

65.57 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−184.1 kJ mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−1460.4 kJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet | ≥99% Sigma-Aldrich | ||

| GHS pictograms |

| ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

| HH220Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors | |||

| PP210Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors, PP377Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors, PP381Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors, PP403Script error: No such module "Preview warning".Category:GHS errors | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −41 °C (−42 °F; 232 K) | ||

| 350 °C (662 °F; 623 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 27 % | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related ethers

|

Diethyl ether | ||

Related compounds

|

Ethanol | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Dimethyl ether (DME; also known as methoxymethane) is the organic compound with the formula CH3OCH3, (sometimes ambiguously simplified to C2H6O as it is an isomer of ethanol). The simplest ether, it is a colorless gas that is a useful precursor to other organic compounds and an aerosol propellant that is currently being demonstrated for use in a variety of fuel applications.

Dimethyl ether was first synthesised by Jean-Baptiste Dumas and Eugene Péligot in 1835 by distillation of methanol and sulfuric acid.[5]

Production

Approximately 50,000 tons were produced in 1985 in Western Europe by dehydration of methanol:[6]

- 2 CH

3OH → (CH

3)

2O + H

2O

The required methanol is obtained from synthesis gas (syngas).[7] Other possible improvements call for a dual catalyst system that permits both methanol synthesis and dehydration in the same process unit, with no methanol isolation and purification.[7][8] Both the one-step and two-step processes above are commercially available. The two-step process is relatively simple and start-up costs are relatively low. A one-step liquid-phase process is in development.[7][9]

From biomass

Dimethyl ether is a synthetic second generation biofuel (BioDME), which can be produced from lignocellulosic biomass.[10] The EU is considering BioDME in its potential biofuel mix in 2030;[11] It can also be made from biogas or methane from animal, food, and agricultural waste,[12][13] or even from shale gas or natural gas.[14]

The Volvo Group is the coordinator for the European Community Seventh Framework Programme project BioDME[15][16] where Chemrec's BioDME pilot plant is based on black liquor gasification in Piteå, Sweden.[17]

Applications

The largest use of dimethyl ether is as the feedstock for the production of the methylating agent, dimethyl sulfate, which entails its reaction with sulfur trioxide:

- CH

3OCH

3 + SO

3 → (CH

3)

2SO

4

Dimethyl ether can also be converted into acetic acid using carbonylation technology related to the Monsanto acetic acid process:[6]

- (CH

3)

2O + 2 CO + H

2O → 2 CH

3CO

2H

Laboratory reagent and solvent

Dimethyl ether is a low-temperature solvent and extraction agent, applicable to specialised laboratory procedures. Its usefulness is limited by its low boiling point (−23 °C (−9 °F)), but the same property facilitates its removal from reaction mixtures. Dimethyl ether is the precursor to the useful alkylating agent, trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate.[18]

Niche applications

A mixture of dimethyl ether and propane is used in some over-the-counter "freeze spray" products to treat warts by freezing them.[19][20] In this role, it has supplanted halocarbon compounds (Freon).

Dimethyl ether is also a component of certain high temperature "Map-Pro" blowtorch gas blends, supplanting the use of methyl acetylene and propadiene mixtures.[21]

Dimethyl ether is also used as a propellant in aerosol products. Such products include hair spray, bug spray and some aerosol glue products.

Research

Fuel

A potentially major use of dimethyl ether is as substitute for propane in LPG used as fuel in household and industry.[22] Dimethyl ether can also be used as a blendstock in propane autogas.[23]

It is also a promising fuel in diesel engines,[24] and gas turbines. For diesel engines, an advantage is the high cetane number of 55, compared to that of diesel fuel from petroleum, which is 40–53.[25] Only moderate modifications are needed to convert a diesel engine to burn dimethyl ether. The simplicity of this short carbon chain compound leads to very low emissions of particulate matter during combustion. For these reasons as well as being sulfur-free, dimethyl ether meets even the most stringent emission regulations in Europe (EURO5), U.S. (U.S. 2010), and Japan (2009 Japan).[26]

At the European Shell Eco Marathon, an unofficial World Championship for mileage, a vehicle running on 100 % dimethyl ether drove 589 km/L (0.170 L per 100 km), fuel equivalent to gasoline with a 50 cm3 displacement 2-stroke engine. As well as winning they beat the old standing record of 306 km/L (0.327 L per 100 km), set by the same team in 2007.[27]

To study the dimethyl ether for the combustion process a chemical kinetic mechanism[28] is required which can be used for Computational fluid dynamics calculation.

Refrigerant

Dimethyl ether is a refrigerant with ASHRAE refrigerant designation R-E170.[29] It is also used in refrigerant blends with e.g. ammonia, carbon dioxide, butane and propene. Dimethyl ether was the first refrigerant. In 1876, the French engineer Charles Tellier bought the ex-Elder-Dempster a 690 tons cargo ship Eboe and fitted a methyl-ether refrigerating plant of his design. The ship was renamed Le Frigorifique and successfully imported a cargo of refrigerated meat from Argentina. However the machinery could be improved and in 1877 another refrigerated ship called Paraguay with a refrigerating plant improved by Ferdinand Carré was put into service on the South American run.[30]

Safety

Unlike other alkyl ethers, dimethyl ether resists autoxidation.[31] Dimethyl ether is also relatively non-toxic, although it is highly flammable. On July 28, 1948, a BASF factory in Ludwigshafen suffered an explosion after 30 tonnes of dimethyl ether leaked from a tank and ignited in the air. 200 people died, and a third of the industrial plant was destroyed.[32]

Data sheet

Routes to produce dimethyl ether

600px

Vapor pressure

| Temperature (K) | Pressure (kPa) |

|---|---|

| 233.128 | 54.61 |

| 238.126 | 68.49 |

| 243.157 | 85.57 |

| 248.152 | 105.59 |

| 253.152 | 129.42 |

| 258.16 | 157.53 |

| 263.16 | 190.44 |

| 268.161 | 228.48 |

| 273.153 | 272.17 |

| 278.145 | 321.87 |

| 283.16 | 378.66 |

| 288.174 | 443.57 |

| 293.161 | 515.53 |

| 298.172 | 596.21 |

| 303.16 | 687.37 |

| 305.16 | 726.26 |

| 308.158 | 787.07 |

| 313.156 | 897.59 |

| 316.154 | 968.55 |

| 318.158 | 1018.91 |

| 323.148 | 1152.35 |

| 328.149 | 1298.23 |

| 333.157 | 1457.5 |

| 333.159 | 1457.76 |

| 338.154 | 1631.01 |

| 343.147 | 1818.8 |

| 348.147 | 2022.45 |

| 353.146 | 2242.74 |

| 353.158 | 2243.07 |

| 358.145 | 2479.92 |

| 363.148 | 2735.67 |

| 368.158 | 3010.81 |

| 373.154 | 3305.67 |

| 378.15 | 3622.6 |

| 383.143 | 3962.25 |

| 388.155 | 4331.48 |

| 393.158 | 4725.02 |

| 398.157 | 5146.82 |

| 400.378 | 5355.8 |

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "CHAPTER P-6. Applications to Specific Classes of Compounds". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 703. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-00648. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ↑ "Dimethylether". 19 October 2018. https://encyclopedia.airliquide.com/dimethylether.

- ↑ GHS: Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ↑ Ann. chim. phys., 1835, [2] 58, p. 19

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Manfred Müller, Ute Hübsch, "Dimethyl Ether" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_541

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "CHEMSYSTEMS.COM". http://www.chemsystems.com/reports/search/docs/abstracts/0708S3_abs.pdf.

- ↑ P.S. Sai Prasad et al., Fuel Processing Technology, 2008, 89, 1281.

- ↑ "Air Products Technology Offerings". http://www.airproducts.com/Technology/product_offering.asp?reg=GBL&intProductTypeCategoryId=95&intRegionalMarketSegment=0.

- ↑ "BioDME". http://www.biodme.eu/.

- ↑ "Biofuels in the European Union, 2006". http://ec.europa.eu/research/energy/pdf/draft_vision_report_en.pdf.

- ↑ "Oberon Fuels Brings Production Units Online, Launching the First North American Fuel-grade DME Facilities". 7 June 2013. http://oberonfuels.com/2013/06/07/oberon-fuels-brings-production-units-online-launching-the-first-north-american-fuel-grade-dme-facilities/.

- ↑ "Associated Gas Utilization via mini GTL". http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTGGFR/Resources/AG_utilization_via_mini_GTL.pdf?resourceurlname=AG_utilization_via_mini_GTL.pdf.

- ↑ Ogawa, Takashi; Inoue, Norio; Shikada, Tutomu; Inokoshi, Osamu; Ohno, Yotaro (2004). "Direct Dimethyl Ether (DME) synthesis from natural gas". Natural Gas Conversion VII, Proceedings of the 7th Natural Gas Conversion Symposium. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis. 147. pp. 379–384. doi:10.1016/S0167-2991(04)80081-8. ISBN 9780444515995.

- ↑ "Home | Volvo Group". http://www.volvo.com/group/global/en-gb/newsmedia/pressreleases/NewsItemPage.htm?channelId=2184&ItemID=47984&sl=en-gb.

- ↑ "Volvo Group - Driving prosperity through transport solutions". http://www.volvo.com/group/global/en-gb/volvo+group/ourvalues/environment/renewable_fuels/biodme/biodme.htm.

- ↑ Chemrec press release September 9, 2010

- ↑ T. J. Curphey (1988). "Trimethyloxonium tetrafluoroborate". Organic Syntheses. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV6P1019.; Collective Volume, 6, pp. 1019

- ↑ "A Pharmacist's Guide to OTC Therapy: OTC Treatments for Warts". July 2006. http://www.pharmacytimes.com/issue/pharmacy/2006/2006-07/2006-07-5674.

- ↑ "Archived copy". https://www.fda.gov/cdrh/pdf3/K030838.pdf.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://images.toolbank.com/downloads/cossh/0482.pdf.

- ↑ "IDA Fact Sheet DME/LPG Blends 2010 v1". http://aboutdme.org/aboutdme/files/ccLibraryFiles/Filename/000000001519/IDA_Fact_Sheet_1_LPG_DME_Blends.pdf.

- ↑ Fleisch, T. H.; Basu, A.; Sills, R. A. (November 2012). "The Status of DME developments in China and beyond, 2012". Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 9: 94–107. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2012.05.012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2012.05.012. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ↑ nycomb.se, Nycomb Chemicals company

- ↑ "Haldor Topsoe - Products & Services - Technologies - DME - Applications - DME as Diesel Fuel". http://www.topsoe.com/site.nsf/all/BBNN-5PNJ3F?OpenDocument. topsoe.com

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.japantransport.com/conferences/2006/03/dme_detailed_information.pdf., Conference on the Development and Promotion of Environmentally Friendly Heavy Duty Vehicles such as DME Trucks, Washington DC, March 17, 2006

- ↑ "The Danish Ecocar Team - List of achievements". http://www.ecocar.mek.dtu.dk/Achievements.aspx.

- ↑ Shrestha, Krishna P.; Eckart, Sven; Elbaz, Ayman M.; Giri, Binod R.; Fritsche, Chris; Seidel, Lars; Roberts, William L.; Krause, Hartmut et al. (2020). "A comprehensive kinetic model for dimethyl ether and dimethoxymethane oxidation and NO interaction utilizing experimental laminar flame speed measurements at elevated pressure and temperature". Combustion and Flame 218: 57–74. doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2020.04.016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.combustflame.2020.04.016. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ↑ "ASHRAE Refrigerant Designations". ASHRAE. 2021-05-25. https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/standards-and-guidelines/ashrae-refrigerant-designations.

- ↑ A history of the frozen meat trade, page 26-28

- ↑ A comparative study on the autoxidation of dimethyl ether (DME) comparison with diethyl ether (DEE) and diisopropyl ether (DIPE), Michie Naito, Claire Radcliffe, Yuji Wada, Takashi Hoshino, Xiongmin Liu, Mitsuru Arai, Masamitsu Tamura. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, Volume 18, Issues 4–6, July–November 2005, Pages 469–473 DOI

- ↑ Welt im Film 167/1948 . filmothek.bundesarchiv.de

- ↑ Wu, Jiangtao; Liu, Zhigang; Pan, Jiang; Zhao, Xiaoming (2003-11-25). "Vapor Pressure Measurements of Dimethyl Ether from (233 to 399) K". J. Chem. Eng. Data 49: 32–34. doi:10.1021/je0340046. https://doi.org/10.1021/je0340046. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

External links

|