Chemistry:Xenon hexafluoroplatinate

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Xenon(I) hexafluoroplatinate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

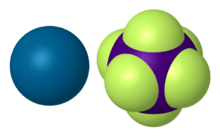

| Xe+[PtF6]− | |

| Molar mass | 440.367 |

| Appearance | orange solid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Xenon hexafluoroplatinate is the product of the reaction of platinum hexafluoride with xenon, in an experiment that proved the chemical reactivity of the noble gases. This experiment was performed by Neil Bartlett at the University of British Columbia, who formulated the product as "Xe+[PtF6]−", although subsequent work suggests that Bartlett's product was probably a salt mixture and did not in fact contain this specific salt.[1]

Preparation

"Xenon hexafluoroplatinate" is prepared from xenon and platinum hexafluoride (PtF6) as gaseous solutions in SF6. The reactants are combined at 77 K and slowly warmed to allow for a controlled reaction.

Structure

The material described originally as "xenon hexafluoroplatinate" is probably not Xe+[PtF6]−. The main problem with this formulation is "Xe+", which would be a radical and would dimerize or abstract a fluorine atom to give XeF+. Thus, Bartlett discovered that Xe undergoes chemical reactions, but the nature and purity of his initial mustard yellow product remains uncertain.[2] Further work indicates that Bartlett's product probably contained [XeF]+[PtF5]−, [XeF]+[Pt2F11]−, and [Xe2F3]+[PtF6]−.[3] The title "compound" is a salt, consisting of an octahedral anionic fluoride complex of platinum and various xenon cations.[4]

It has been proposed that the platinum fluoride forms a negatively charged polymeric network with xenon or xenon fluoride cations held in its interstices. A preparation of "XePtF6" in HF solution results in a solid which has been characterized as a [PtF5]− polymeric network associated with XeF+. This result is evidence for such a polymeric structure of xenon hexafluoroplatinate.[2]

History

In 1962, Neil Bartlett discovered that a mixture of platinum hexafluoride gas and oxygen formed a red solid.[5][6] The red solid turned out to be dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate, O+2[PtF6]−. Bartlett noticed that the ionization energy for O2 (1175 kJ mol−1) was very close to the ionization energy for Xe (1170 kJ mol−1). He then asked his colleagues to give him some xenon "so that he could try out some reactions",[7] whereupon he established that xenon indeed reacts with PtF6. Although, as discussed above, the product was probably a mixture of several compounds, Bartlett's work was the first proof that compounds could be prepared from a noble gas. Since Bartlett's observation, many well-defined compounds of xenon have been reported including XeF2, XeF4, and XeF6.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. ISBN 0080379419.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Graham, Lionell; Graudejus, Oliver; Jha, Narendra K.; Bartlett, Neil (2000). "Concerning the nature of XePtF6". Coordination Chemistry Reviews 197 (1): 321–334. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00190-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Holleman, Arnold Frederick; Wiberg, Egon (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑ Sampson, Mark T. (May 23, 2006). Neil Bartlett and the Reactive Noble Gases. National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. https://www.acs.org/content/dam/acsorg/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/bartlettnoblegases/neil-bartlett-reactive-noble-gases-commemorative-booklet.pdf. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ↑ Bartlett, Neil (1962). "Xenon hexafluoroplatinate(V) Xe+[PtF6]−". Proceedings of the Chemical Society 1962 (6): 197–236. doi:10.1039/PS9620000197.

- ↑ Bartlett, Neil; Lohmann, D. H. (1962). "Dioxygenyl hexafluoroplatinate(V), O+2[PtF6]−". Proceedings of the Chemical Society 1962 (3): 97–132. doi:10.1039/PS9620000097.

- ↑ Clugston, Michael; Flemming, Rosalind (2000). Advanced Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0199146338.

|