Biology:RNA

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

| Key components |

| History and topics |

| Research |

| Personalized medicine |

| Personalized medicine |

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) are nucleic acids. The nucleic acids constitute one of the four major macromolecules essential for all known forms of life. RNA is assembled as a chain of nucleotides. Cellular organisms use messenger RNA (mRNA) to convey genetic information (using the nitrogenous bases of guanine, uracil, adenine, and cytosine, denoted by the letters G, U, A, and C) that directs synthesis of specific proteins. Many viruses encode their genetic information using an RNA genome.

Some RNA molecules play an active role within cells by catalyzing biological reactions, controlling gene expression, or sensing and communicating responses to cellular signals. One of these active processes is protein synthesis, a universal function in which RNA molecules direct the synthesis of proteins on ribosomes. This process uses transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules to deliver amino acids to the ribosome, where ribosomal RNA (rRNA) then links amino acids together to form coded proteins.

It has become widely accepted in science[1] that early in the history of life on Earth, prior to the evolution of DNA and possibly of protein-based enzymes as well, an "RNA world" existed in which RNA served as both living organisms' storage method for genetic information—a role fulfilled today by DNA, except in the case of RNA viruses—and potentially performed catalytic functions in cells—a function performed today by protein enzymes, with the notable and important exception of the ribosome, which is a ribozyme.

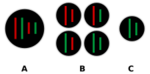

Comparison with DNA

Like DNA, most biologically active RNAs, including mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, snRNAs, and other non-coding RNAs, contain self-complementary sequences that allow parts of the RNA to fold[6] and pair with itself to form double helices. Analysis of these RNAs has revealed that they are highly structured. Unlike DNA, their structures do not consist of long double helices, but rather collections of short helices packed together into structures akin to proteins.

In this fashion, RNAs can achieve chemical catalysis (like enzymes).[7] For instance, determination of the structure of the ribosome—an RNA-protein complex that catalyzes peptide bond formation—revealed that its active site is composed entirely of RNA.[8]

Structure

Each nucleotide in RNA contains a ribose sugar, with carbons numbered 1' through 5'. A base is attached to the 1' position, in general, adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), or uracil (U). Adenine and guanine are purines, cytosine and uracil are pyrimidines. A phosphate group is attached to the 3' position of one ribose and the 5' position of the next. The phosphate groups have a negative charge each, making RNA a charged molecule (polyanion). The bases form hydrogen bonds between cytosine and guanine, between adenine and uracil and between guanine and uracil.[9] However, other interactions are possible, such as a group of adenine bases binding to each other in a bulge,[10] or the GNRA tetraloop that has a guanine–adenine base-pair.[9]

An important structural component of RNA that distinguishes it from DNA is the presence of a hydroxyl group at the 2' position of the ribose sugar. The presence of this functional group causes the helix to mostly take the A-form geometry,[11] although in single strand dinucleotide contexts, RNA can rarely also adopt the B-form most commonly observed in DNA.[12] The A-form geometry results in a very deep and narrow major groove and a shallow and wide minor groove.[13] A second consequence of the presence of the 2'-hydroxyl group is that in conformationally flexible regions of an RNA molecule (that is, not involved in formation of a double helix), it can chemically attack the adjacent phosphodiester bond to cleave the backbone.[14]

RNA is transcribed with only four bases (adenine, cytosine, guanine and uracil),[15] but these bases and attached sugars can be modified in numerous ways as the RNAs mature. Pseudouridine (Ψ), in which the linkage between uracil and ribose is changed from a C–N bond to a C–C bond, and ribothymidine (T) are found in various places (the most notable ones being in the TΨC loop of tRNA).[16] Another notable modified base is hypoxanthine, a deaminated adenine base whose nucleoside is called inosine (I). Inosine plays a key role in the wobble hypothesis of the genetic code.[17]

There are more than 100 other naturally occurring modified nucleosides.[18] The greatest structural diversity of modifications can be found in tRNA,[19] while pseudouridine and nucleosides with 2'-O-methylribose often present in rRNA are the most common.[20] The specific roles of many of these modifications in RNA are not fully understood. However, it is notable that, in ribosomal RNA, many of the post-transcriptional modifications occur in highly functional regions, such as the peptidyl transferase center [21] and the subunit interface, implying that they are important for normal function.[22]

The functional form of single-stranded RNA molecules, just like proteins, frequently requires a specific tertiary structure. The scaffold for this structure is provided by secondary structural elements that are hydrogen bonds within the molecule. This leads to several recognizable "domains" of secondary structure like hairpin loops, bulges, and internal loops.[23] In order create, i.e., design, a RNA for any given secondary structure, two or three bases would not be enough, but four bases are enough.[24] This is likely why nature has "chosen" a four base alphabet: less than four does not allow to create all structures, while more than four bases are not necessary. Since RNA is charged, metal ions such as Mg2+ are needed to stabilise many secondary and tertiary structures.[25]

The naturally occurring enantiomer of RNA is D-RNA composed of D-ribonucleotides. All chirality centers are located in the D-ribose. By the use of L-ribose or rather L-ribonucleotides, L-RNA can be synthesized. L-RNA is much more stable against degradation by RNase.[26]

Like other structured biopolymers such as proteins, one can define topology of a folded RNA molecule. This is often done based on arrangement of intra-chain contacts within a folded RNA, termed as circuit topology.

Synthesis

Synthesis of RNA is usually catalyzed by an enzyme—RNA polymerase—using DNA as a template, a process known as transcription. Initiation of transcription begins with the binding of the enzyme to a promoter sequence in the DNA (usually found "upstream" of a gene). The DNA double helix is unwound by the helicase activity of the enzyme. The enzyme then progresses along the template strand in the 3’ to 5’ direction, synthesizing a complementary RNA molecule with elongation occurring in the 5’ to 3’ direction. The DNA sequence also dictates where termination of RNA synthesis will occur.[27]

Primary transcript RNAs are often modified by enzymes after transcription. For example, a poly(A) tail and a 5' cap are added to eukaryotic pre-mRNA and introns are removed by the spliceosome.

There are also a number of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases that use RNA as their template for synthesis of a new strand of RNA. For instance, a number of RNA viruses (such as poliovirus) use this type of enzyme to replicate their genetic material.[28] Also, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is part of the RNA interference pathway in many organisms.[29]

Types of RNA

Overview

Messenger RNA (mRNA) is the RNA that carries information from DNA to the ribosome, the sites of protein synthesis (translation) in the cell. The mRNA is a copy of DNA. The coding sequence of the mRNA determines the amino acid sequence in the protein that is produced.[30] However, many RNAs do not code for protein (about 97% of the transcriptional output is non-protein-coding in eukaryotes[31][32][33][34]).

These so-called non-coding RNAs ("ncRNA") can be encoded by their own genes (RNA genes), but can also derive from mRNA introns.[35] The most prominent examples of non-coding RNAs are transfer RNA (tRNA) and ribosomal RNA (rRNA), both of which are involved in the process of translation.[5] There are also non-coding RNAs involved in gene regulation, RNA processing and other roles. Certain RNAs are able to catalyse chemical reactions such as cutting and ligating other RNA molecules,[36] and the catalysis of peptide bond formation in the ribosome;[8] these are known as ribozymes.

In length

According to the length of RNA chain, RNA includes small RNA and long RNA.[37] Usually, small RNAs are shorter than 200 nt in length, and long RNAs are greater than 200 nt long.[38] Long RNAs, also called large RNAs, mainly include long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) and mRNA. Small RNAs mainly include 5.8S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), 5S rRNA, transfer RNA (tRNA), microRNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNAs), Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA), tRNA-derived small RNA (tsRNA)[39] and small rDNA-derived RNA (srRNA).[40] There are certain exceptions as in the case of the 5S rRNA of the members of the genus Halococcus (Archaea), which have an insertion, thus increasing its size.[41][42][43]

In translation

Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries information about a protein sequence to the ribosomes, the protein synthesis factories in the cell. It is coded so that every three nucleotides (a codon) corresponds to one amino acid. In eukaryotic cells, once precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) has been transcribed from DNA, it is processed to mature mRNA. This removes its introns—non-coding sections of the pre-mRNA. The mRNA is then exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where it is bound to ribosomes and translated into its corresponding protein form with the help of tRNA. In prokaryotic cells, which do not have nucleus and cytoplasm compartments, mRNA can bind to ribosomes while it is being transcribed from DNA. After a certain amount of time, the message degrades into its component nucleotides with the assistance of ribonucleases.[30]

Transfer RNA (tRNA) is a small RNA chain of about 80 nucleotides that transfers a specific amino acid to a growing polypeptide chain at the ribosomal site of protein synthesis during translation. It has sites for amino acid attachment and an anticodon region for codon recognition that binds to a specific sequence on the messenger RNA chain through hydrogen bonding.[35]

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is the catalytic component of the ribosomes. The rRNA is the component of the ribosome that hosts translation. Eukaryotic ribosomes contain four different rRNA molecules: 18S, 5.8S, 28S and 5S rRNA. Three of the rRNA molecules are synthesized in the nucleolus, and one is synthesized elsewhere. In the cytoplasm, ribosomal RNA and protein combine to form a nucleoprotein called a ribosome. The ribosome binds mRNA and carries out protein synthesis. Several ribosomes may be attached to a single mRNA at any time.[30] Nearly all the RNA found in a typical eukaryotic cell is rRNA.

Transfer-messenger RNA (tmRNA) is found in many bacteria and plastids. It tags proteins encoded by mRNAs that lack stop codons for degradation and prevents the ribosome from stalling.[44]

Regulatory RNA

The earliest known regulators of gene expression were proteins known as repressors and activators – regulators with specific short binding sites within enhancer regions near the genes to be regulated.[45] Later studies have shown that RNAs also regulate genes. There are several kinds of RNA-dependent processes in eukaryotes regulating the expression of genes at various points, such as RNAi repressing genes post-transcriptionally, long non-coding RNAs shutting down blocks of chromatin epigenetically, and enhancer RNAs inducing increased gene expression.[46] Bacteria and archaea have also been shown to use regulatory RNA systems such as bacterial small RNAs and CRISPR.[47] Fire and Mello were awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering microRNAs (miRNAs), specific short RNA molecules that can base-pair with mRNAs.[48]

RNA interference by miRNAs

Post-transcriptional expression levels of many genes can be controlled by RNA interference, in which miRNAs, specific short RNA molecules, pair with mRNA regions and target them for degradation.[49] This antisense-based process involves steps that first process the RNA so that it can base-pair with a region of its target mRNAs. Once the base pairing occurs, other proteins direct the mRNA to be destroyed by nucleases.[46]

Long non-coding RNAs

Next to be linked to regulation were Xist and other long noncoding RNAs associated with X chromosome inactivation. Their roles, at first mysterious, were shown by Jeannie T. Lee and others to be the silencing of blocks of chromatin via recruitment of Polycomb complex so that messenger RNA could not be transcribed from them.[50] Additional lncRNAs, currently defined as RNAs of more than 200 base pairs that do not appear to have coding potential,[51] have been found associated with regulation of stem cell pluripotency and cell division.[51]

Enhancer RNAs

The third major group of regulatory RNAs is called enhancer RNAs.[51] It is not clear at present whether they are a unique category of RNAs of various lengths or constitute a distinct subset of lncRNAs. In any case, they are transcribed from enhancers, which are known regulatory sites in the DNA near genes they regulate.[51][52] They up-regulate the transcription of the gene(s) under control of the enhancer from which they are transcribed.[51][53]

Regulatory RNA in prokaryotes

At first, regulatory RNA was thought to be a eukaryotic phenomenon, a part of the explanation for why so much more transcription in higher organisms was seen than had been predicted. But as soon as researchers began to look for possible RNA regulators in bacteria, they turned up there as well, termed as small RNA (sRNA).[54][47] Currently, the ubiquitous nature of systems of RNA regulation of genes has been discussed as support for the RNA World theory.[46][55] There are indications that the enterobacterial sRNAs are involved in various cellular processes and seem to have significant role in stress responses such as membrane stress, starvation stress, phosphosugar stress and DNA damage. Also, it has been suggested that sRNAs have been evolved to have important role in stress responses because of their kinetic properties that allow for rapid response and stabilisation of the physiological state.[2] Bacterial small RNAs generally act via antisense pairing with mRNA to down-regulate its translation, either by affecting stability or affecting cis-binding ability.[46] Riboswitches have also been discovered. They are cis-acting regulatory RNA sequences acting allosterically. They change shape when they bind metabolites so that they gain or lose the ability to bind chromatin to regulate expression of genes.[56][57]

Archaea also have systems of regulatory RNA.[58] The CRISPR system, recently being used to edit DNA in situ, acts via regulatory RNAs in archaea and bacteria to provide protection against virus invaders.[46][59]

In RNA processing

Many RNAs are involved in modifying other RNAs. Introns are spliced out of pre-mRNA by spliceosomes, which contain several small nuclear RNAs (snRNA),[5] or the introns can be ribozymes that are spliced by themselves.[60] RNA can also be altered by having its nucleotides modified to nucleotides other than A, C, G and U. In eukaryotes, modifications of RNA nucleotides are in general directed by small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNA; 60–300 nt),[35] found in the nucleolus and cajal bodies. snoRNAs associate with enzymes and guide them to a spot on an RNA by basepairing to that RNA. These enzymes then perform the nucleotide modification. rRNAs and tRNAs are extensively modified, but snRNAs and mRNAs can also be the target of base modification.[61][62] RNA can also be methylated.[63][64]

RNA genomes

Like DNA, RNA can carry genetic information. RNA viruses have genomes composed of RNA that encodes a number of proteins. The viral genome is replicated by some of those proteins, while other proteins protect the genome as the virus particle moves to a new host cell. Viroids are another group of pathogens, but they consist only of RNA, do not encode any protein and are replicated by a host plant cell's polymerase.[65]

In reverse transcription

Reverse transcribing viruses replicate their genomes by reverse transcribing DNA copies from their RNA; these DNA copies are then transcribed to new RNA. Retrotransposons also spread by copying DNA and RNA from one another,[66] and telomerase contains an RNA that is used as template for building the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes.[67]

Double-stranded RNA

Double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is RNA with two complementary strands, similar to the DNA found in all cells, but with the replacement of thymine by uracil and the adding of one oxygen atom. dsRNA forms the genetic material of some viruses (double-stranded RNA viruses). Double-stranded RNA, such as viral RNA or siRNA, can trigger RNA interference in eukaryotes, as well as interferon response in vertebrates.[68][69][70][71] In eukaryotes, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) plays a role in the activation of the innate immune system against viral infections.[72]

Circular RNA

In the late 1970s, it was shown that there is a single stranded covalently closed, i.e. circular form of RNA expressed throughout the animal and plant kingdom (see circRNA).[73] circRNAs are thought to arise via a "back-splice" reaction where the spliceosome joins a upstream 3' acceptor to a downstream 5' donor splice site. So far the function of circRNAs is largely unknown, although for few examples a microRNA sponging activity has been demonstrated.

Key discoveries in RNA biology

Research on RNA has led to many important biological discoveries and numerous Nobel Prizes. Nucleic acids were discovered in 1868 by Friedrich Miescher, who called the material 'nuclein' since it was found in the nucleus.[74] It was later discovered that prokaryotic cells, which do not have a nucleus, also contain nucleic acids. The role of RNA in protein synthesis was suspected already in 1939.[75] Severo Ochoa won the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine (shared with Arthur Kornberg) after he discovered an enzyme that can synthesize RNA in the laboratory.[76] However, the enzyme discovered by Ochoa (polynucleotide phosphorylase) was later shown to be responsible for RNA degradation, not RNA synthesis. In 1956 Alex Rich and David Davies hybridized two separate strands of RNA to form the first crystal of RNA whose structure could be determined by X-ray crystallography.[77]

The sequence of the 77 nucleotides of a yeast tRNA was found by Robert W. Holley in 1965,[78] winning Holley the 1968 Nobel Prize in Medicine (shared with Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall Nirenberg).

In the early 1970s, retroviruses and reverse transcriptase were discovered, showing for the first time that enzymes could copy RNA into DNA (the opposite of the usual route for transmission of genetic information). For this work, David Baltimore, Renato Dulbecco and Howard Temin were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1975. In 1976, Walter Fiers and his team determined the first complete nucleotide sequence of an RNA virus genome, that of bacteriophage MS2.[79]

In 1977, introns and RNA splicing were discovered in both mammalian viruses and in cellular genes, resulting in a 1993 Nobel to Philip Sharp and Richard Roberts. Catalytic RNA molecules (ribozymes) were discovered in the early 1980s, leading to a 1989 Nobel award to Thomas Cech and Sidney Altman. In 1990, it was found in Petunia that introduced genes can silence similar genes of the plant's own, now known to be a result of RNA interference.[80][81]

At about the same time, 22 nt long RNAs, now called microRNAs, were found to have a role in the development of C. elegans.[82] Studies on RNA interference gleaned a Nobel Prize for Andrew Fire and Craig Mello in 2006, and another Nobel was awarded for studies on the transcription of RNA to Roger Kornberg in the same year. The discovery of gene regulatory RNAs has led to attempts to develop drugs made of RNA, such as siRNA, to silence genes.[83] Adding to the Nobel prizes awarded for research on RNA in 2009 it was awarded for the elucidation of the atomic structure of the ribosome to Venki Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz, and Ada Yonath.

Relevance for prebiotic chemistry and abiogenesis

In 1968, Carl Woese hypothesized that RNA might be catalytic and suggested that the earliest forms of life (self-replicating molecules) could have relied on RNA both to carry genetic information and to catalyze biochemical reactions—an RNA world.[84][85] In May 2022, scientists reported that they discovered RNA forms spontaneously on prebiotic basalt lava glass which is presumed to have been abundantly available on the early Earth.[86][87]

In March 2015, DNA and RNA nucleobases, including uracil, cytosine and thymine, were reportedly formed in the laboratory under outer space conditions, using starter chemicals, such as pyrimidine, an organic compound commonly found in meteorites. Pyrimidine, like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), is one of the most carbon-rich compounds found in the Universe and may have been formed in red giants or in interstellar dust and gas clouds.[88] In July 2022, astronomers reported the discovery of massive amounts of prebiotic molecules, including possible RNA precursors, in the Galactic Center of the Milky Way Galaxy.[89][90]

See also

- Biomolecular structure

- RNA virus

- DNA

- History of RNA Biology

- List of RNA Biologists

- RNA Society

- Macromolecule

- RNA-based evolution

- Aptamer

- RNA origami

- Transcriptome

- RNA world hypothesis

References

- ↑ "The origin of the RNA world: co-evolution of genes and metabolism". Bioorganic Chemistry 35 (6): 430–443. December 2007. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2007.08.001. PMID 17897696. "The proposal that life on Earth arose from an RNA World is widely accepted.".

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "RNA: The Versatile Molecule". University of Utah. 2015. https://learn.genetics.utah.edu/content/basics/rna/.

- ↑ "Nucleotides and Nucleic Acids". University of California, Los Angeles. http://www.chem.ucla.edu/harding/notes/notes_14C_nucacids.pdf.

- ↑ Analysis of Chromosomes. 2014. ISBN 978-93-84568-17-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=7-UKCgAAQBAJ&q=dna+contains+deoxyribose+rna+ribose&pg=PT386.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Biochemistry (5th ed.). WH Freeman and Company. 2002. pp. 118–19, 781–808. ISBN 978-0-7167-4684-3. OCLC 179705944.

- ↑ "How RNA folds". Journal of Molecular Biology 293 (2): 271–81. October 1999. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1999.3001. PMID 10550208.

- ↑ "RNA secondary structure: physical and computational aspects". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics 33 (3): 199–253. August 2000. doi:10.1017/S0033583500003620. PMID 11191843.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The structural basis of ribosome activity in peptide bond synthesis". Science 289 (5481): 920–30. August 2000. doi:10.1126/science.289.5481.920. PMID 10937990. Bibcode: 2000Sci...289..920N.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Diversity of base-pair conformations and their occurrence in rRNA structure and RNA structural motifs". Journal of Molecular Biology 344 (5): 1225–49. December 2004. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.072. PMID 15561141.

- ↑ RNA biochemistry and biotechnology. Springer. 1999. pp. 73–87. ISBN 978-0-7923-5862-6. OCLC 52403776.

- ↑ "The DNA strand in DNA.RNA hybrid duplexes is neither B-form nor A-form in solution". Biochemistry 32 (16): 4207–15. April 1993. doi:10.1021/bi00067a007. PMID 7682844.

- ↑ "RNA approaches the B-form in stacked single strand dinucleotide contexts". Biopolymers 105 (2): 65–82. February 2016. doi:10.1002/bip.22750. PMID 26443416.

- ↑ "RNA bulges as architectural and recognition motifs". Structure 8 (3): R47–54. March 2000. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(00)00110-6. PMID 10745015.

- ↑ "The mechanism of the metal ion promoted cleavage of RNA phosphodiester bonds involves a general acid catalysis by the metal aquo ion on the departure of the leaving group". Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 (8): 1619–26. 1999. doi:10.1039/a903691a.

- ↑ Clinical gene analysis and manipulation: Tools, techniques and troubleshooting. Cambridge University Press. 1996. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-521-47896-0. OCLC 33838261. https://archive.org/details/clinicalgeneanal0000unse/page/14.

- ↑ "Identification of critical elements in the tRNA acceptor stem and T(Psi)C loop necessary for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity". Journal of Virology 75 (10): 4902–6. May 2001. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.10.4902-4906.2001. PMID 11312362.

- ↑ "Inosine biosynthesis in transfer RNA by an enzymatic insertion of hypoxanthine". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 259 (4): 2407–10. February 1984. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)43367-9. PMID 6365911.

- ↑ "The RNA Modification Database, RNAMDB: 2011 update". Nucleic Acids Research 39 (Database issue): D195-201. January 2011. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq1028. PMID 21071406.

- ↑ TRNA: Structure, biosynthesis, and function. ASM Press. 1995. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-55581-073-3. OCLC 183036381.

- ↑ "Small nucleolar RNA-guided post-transcriptional modification of cellular RNAs". The EMBO Journal 20 (14): 3617–22. July 2001. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.14.3617. PMID 11447102.

- ↑ "The Peptidyl Transferase Center: a Window to the Past.". Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 85 (4): e0010421. November 2021. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00104-21. PMID 34756086.

- ↑ "Ribosome structure and activity are altered in cells lacking snoRNPs that form pseudouridines in the peptidyl transferase center". Molecular Cell 11 (2): 425–35. February 2003. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00040-6. PMID 12620230.

- ↑ "Incorporating chemical modification constraints into a dynamic programming algorithm for prediction of RNA secondary structure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (19): 7287–92. May 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401799101. PMID 15123812. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.7287M.

- ↑ "RNA secondary structure design". Physical Review E 75 (2): 021920. February 2007. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.75.021920. PMID 17358380. Bibcode: 2007PhRvE..75b1920B. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.75.021920.

- ↑ "Salt dependence of nucleic acid hairpin stability". Biophysical Journal 95 (2): 738–52. July 2008. doi:10.1529/biophysj.108.131524. PMID 18424500. Bibcode: 2008BpJ....95..738T.

- ↑ "Turning mirror-image oligonucleotides into drugs: the evolution of Spiegelmer(®) therapeutics". Drug Discovery Today 20 (1): 147–55. January 2015. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.004. PMID 25236655.

- ↑ "Transcription termination and anti-termination in E. coli". Genes to Cells 7 (8): 755–68. August 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00563.x. PMID 12167155.

- ↑ "Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of poliovirus". Structure 5 (8): 1109–22. August 1997. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00261-X. PMID 9309225.

- ↑ "RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, viruses, and RNA silencing". Science 296 (5571): 1270–73. May 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1069132. PMID 12016304. Bibcode: 2002Sci...296.1270A.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 The Cell: A Molecular Approach (3rd ed.). Sinauer. 2004. pp. 261–76, 297, 339–44. ISBN 978-0-87893-214-6. OCLC 174924833.

- ↑ "The evolution of controlled multitasked gene networks: the role of introns and other noncoding RNAs in the development of complex organisms". Molecular Biology and Evolution 18 (9): 1611–30. September 2001. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003951. PMID 11504843.

- ↑ "Non-coding RNAs: the architects of eukaryotic complexity". EMBO Reports 2 (11): 986–91. November 2001. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve230. PMID 11713189.

- ↑ "Challenging the dogma: the hidden layer of non-protein-coding RNAs in complex organisms". BioEssays 25 (10): 930–39. October 2003. doi:10.1002/bies.10332. PMID 14505360. http://www.imb-jena.de/jcb/journal_club/mattick2003.pdf.

- ↑ "The hidden genetic program of complex organisms". Scientific American 291 (4): 60–67. October 2004. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1004-60. PMID 15487671. Bibcode: 2004SciAm.291d..60M.[|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Mining the transcriptome – methods and applications. Stockholm: School of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology. 2006. ISBN 978-91-7178-436-0. OCLC 185406288. http://kth.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:10803/FULLTEXT01.

- ↑ "Ribozyme diagnostics comes of age". Chemistry & Biology 11 (7): 894–95. July 2004. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.07.002. PMID 15271347.

- ↑ "An expanding universe of noncoding RNAs". Science 296 (5571): 1260–63. May 2002. doi:10.1126/science.1072249. PMID 12016301. Bibcode: 2002Sci...296.1260S.

- ↑ "Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development". Nature Reviews Genetics 15 (1): 7–21. January 2014. doi:10.1038/nrg3606. PMID 24296535. https://hal-riip.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-01160208/document.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder". Science 351 (6271): 397–400. January 2016. doi:10.1126/science.aad7977. PMID 26721680. Bibcode: 2016Sci...351..397C. https://escholarship.org/content/qt6x66v4k6/qt6x66v4k6.pdf?t=plrd95.

- ↑ "Profiling and identification of small rDNA-derived RNAs and their potential biological functions". PLOS ONE 8 (2): e56842. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056842. PMID 23418607. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...856842W.

- ↑ "An archaebacterial 5S rRNA contains a long insertion sequence.". Nature 293 (5835): 755–756. 1981. doi:10.1038/293755a0. PMID 6169998. Bibcode: 1981Natur.293..755L.

- ↑ "Very similar strains of Halococcus salifodinae are found in geographically separated permo-triassic salt deposits.". Microbiology 145 (Pt 12): 3565–3574. 1999. doi:10.1099/00221287-145-12-3565. PMID 10627054.

- ↑ "Cryo-Electron Microscopy Visualization of a Large Insertion in the 5S ribosomal RNA of the Extremely Halophilic Archaeon Halococcus morrhuae". FEBS Open Bio 10 (10): 1938–1946. August 2020. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12962. PMID 32865340.

- ↑ "The tmRNA website: reductive evolution of tmRNA in plastids and other endosymbionts". Nucleic Acids Research 32 (Database issue): D104–08. January 2004. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh102. PMID 14681369.

- ↑ "Genetic Regulatory Mechanisms in the Synthesis of Proteins". Journal of Molecular Biology 3 (3): 318–56. 1961. doi:10.1016/s0022-2836(61)80072-7. PMID 13718526.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 "The rise of regulatory RNA". Nature Reviews Genetics 15 (6): 423–37. 2014. doi:10.1038/nrg3722. PMID 24776770.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "Micros for microbes: non-coding regulatory RNAs in bacteria". Trends in Genetics 21 (7): 399–404. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.008. PMID 15913835.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2006". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 6 Aug 2018. http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2006

- ↑ "Potent and Specific Genetic Interference by double stranded RNA in Ceanorhabditis elegans". Nature 391 (6669): 806–11. 1998. doi:10.1038/35888. PMID 9486653. Bibcode: 1998Natur.391..806F.

- ↑ "Polycomb proteins targeted by a short repeat RNA to the mouse X chromosome". Science 322 (5902): 750–56. 2008. doi:10.1126/science.1163045. PMID 18974356. Bibcode: 2008Sci...322..750Z.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 "Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81: 1–25. 2012. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-051410-092902. PMID 22663078.

- ↑ "Evolution, biogenesis and function of promoter- associated RNAs". Cell Cycle 8 (15): 2332–38. 2009. doi:10.4161/cc.8.15.9154. PMID 19597344.

- ↑ "'Long noncoding RNAs with enhancer-like function in human cells". Cell 143 (1): 46–58. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.001. PMID 20887892.

- ↑ EGH Wagner, P Romby. (2015). "Small RNAs in bacteria and archaea: who they are, what they do, and how they do it". Advances in genetics (Vol. 90, pp. 133–208).

- ↑ J.W. Nelson, R.R. Breaker (2017) "The lost language of the RNA World."Sci. Signal.10, eaam8812 1–11.

- ↑ "Riboswitches and the role of noncoding RNAs in bacterial metabolic control". Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 9 (6): 594–602. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.09.016. PMID 16226486.

- ↑ "Riboswitches as versatile gene control elements". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15 (3): 342–48. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2005.05.003. PMID 15919195.

- ↑ "" "Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of archaea, bacteria and mitochondria". Mol. Microbiol. 36 (1): 244–46. 2000. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01838.x. PMID 10760181.

- ↑ "Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes". Science 321 (5891): 960–64. 2008. doi:10.1126/science.1159689. PMID 18703739. Bibcode: 2008Sci...321..960B.

- ↑ "A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 90 (14): 6498–502. July 1993. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. PMID 8341661. Bibcode: 1993PNAS...90.6498S.

- ↑ "Sno/scaRNAbase: a curated database for small nucleolar RNAs and cajal body-specific RNAs". Nucleic Acids Research 35 (Database issue): D183–87. January 2007. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl873. PMID 17099227.

- ↑ "RNA-modifying machines in archaea". Molecular Microbiology 48 (3): 617–29. May 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03483.x. PMID 12694609.

- ↑ "Targeted ribose methylation of RNA in vivo directed by tailored antisense RNA guides". Nature 383 (6602): 732–35. October 1996. doi:10.1038/383732a0. PMID 8878486. Bibcode: 1996Natur.383..732C.

- ↑ "Site-specific ribose methylation of preribosomal RNA: a novel function for small nucleolar RNAs". Cell 85 (7): 1077–88. June 1996. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81308-2. PMID 8674114.

- ↑ "Viroids: an Ariadne's thread into the RNA labyrinth". EMBO Reports 7 (6): 593–98. June 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400706. PMID 16741503.

- ↑ "Large retrotransposon derivatives: abundant, conserved but nonautonomous retroelements of barley and related genomes". Genetics 166 (3): 1437–50. March 2004. doi:10.1534/genetics.166.3.1437. PMID 15082561.

- ↑ "The telomerase database". Nucleic Acids Research 36 (Database issue): D339–43. January 2008. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm700. PMID 18073191.

- ↑ "Four plant Dicers mediate viral small RNA biogenesis and DNA virus induced silencing". Nucleic Acids Research 34 (21): 6233–46. 2006. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl886. PMID 17090584.

- ↑ "RNA interference: potential therapeutic targets". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 65 (6): 649–57. November 2004. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1732-1. PMID 15372214.

- ↑ Virol, J (May 2006). "Double-Stranded RNA Is Produced by Positive-Strand RNA Viruses and DNA Viruses but Not in Detectable Amounts by Negative-Strand RNA Viruses". Journal of Virology 80 (10): 5059–5064. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.10.5059-5064.2006. PMID 16641297.

- ↑ "The interferon system of non-mammalian vertebrates". Developmental and Comparative Immunology 28 (5): 499–508. May 2004. doi:10.1016/j.dci.2003.09.009. PMID 15062646.

- ↑ "Silencing or stimulation? siRNA delivery and the immune system". Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 2: 77–96. 2011. doi:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-061010-114133. PMID 22432611.

- ↑ "Electron microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells" (in En). Nature 280 (5720): 339–40. July 1979. doi:10.1038/280339a0. PMID 460409. Bibcode: 1979Natur.280..339H.

- ↑ "Friedrich Miescher and the discovery of DNA". Developmental Biology 278 (2): 274–88. February 2005. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.028. PMID 15680349.

- ↑ "Pentose nucleotides in the cytoplasm of growing tissues". Nature 143 (3623): 602–03. 1939. doi:10.1038/143602c0. Bibcode: 1939Natur.143..602C.

- ↑ "Enzymatic synthesis of ribonucleic acid". Nobel Lecture. 1959. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1959/ochoa-lecture.pdf.

- ↑ "A New Two-Stranded Helical Structure: Polyadenylic Acid and Polyuridylic Acid". Journal of the American Chemical Society 78 (14): 3548–49. 1956. doi:10.1021/ja01595a086.

- ↑ "Structure of a ribonucleic acid". Science 147 (3664): 1462–65. March 1965. doi:10.1126/science.147.3664.1462. PMID 14263761. Bibcode: 1965Sci...147.1462H.

- ↑ "Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene". Nature 260 (5551): 500–07. April 1976. doi:10.1038/260500a0. PMID 1264203. Bibcode: 1976Natur.260..500F.

- ↑ "Introduction of a Chimeric Chalcone Synthase Gene into Petunia Results in Reversible Co-Suppression of Homologous Genes in trans". The Plant Cell 2 (4): 279–89. April 1990. doi:10.1105/tpc.2.4.279. PMID 12354959.

- ↑ "pSAT RNA interference vectors: a modular series for multiple gene down-regulation in plants". Plant Physiology 145 (4): 1272–81. December 2007. doi:10.1104/pp.107.106062. PMID 17766396.

- ↑ "Molecular biology. Glimpses of a tiny RNA world". Science 294 (5543): 797–99. October 2001. doi:10.1126/science.1066315. PMID 11679654.

- ↑ "The potential of oligonucleotides for therapeutic applications". Trends in Biotechnology 24 (12): 563–70. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.003. PMID 17045686.

- ↑ "Common sequence structure properties and stable regions in RNA secondary structures". Dissertation, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, Freiburg im Breisgau. 2006. p. 1. http://deposit.ddb.de/cgi-bin/dokserv?idn=982323891&dok_var=d1&dok_ext=pdf&filename=982323891.pdf.

- ↑ "The origin of the genetic code: amino acids as cofactors in an RNA world". Trends in Genetics 15 (6): 223–29. June 1999. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01730-8. PMID 10354582.

- ↑ Jerome, Craig A. (19 May 2022). "Catalytic Synthesis of Polyribonucleic Acid on Prebiotic Rock Glasses". Astrobiology 22 (6): 629–636. doi:10.1089/ast.2022.0027. PMID 35588195. Bibcode: 2022AsBio..22..629J.

- ↑ Foundation for Applied Molecular Evolution (3 June 2022). "Scientists announce a breakthrough in determining life's origin on Earth—and maybe Mars". Phys.org. https://phys.org/news/2022-06-scientists-breakthrough-life-earthand-mars.html. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- ↑ Marlaire, Ruth (3 March 2015). "NASA Ames Reproduces the Building Blocks of Life in Laboratory". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/content/nasa-ames-reproduces-the-building-blocks-of-life-in-laboratory.

- ↑ Starr, Michelle (8 July 2022). "Loads of Precursors For RNA Have Been Detected in The Center of Our Galaxy". ScienceAlert. https://www.sciencealert.com/scientists-have-found-a-bunch-of-rna-precursors-in-the-galactic-center. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ Rivilla, Victor M. (8 July 2022). "Molecular Precursors of the RNA-World in Space: New Nitriles in the G+0.693–0.027 Molecular Cloud". Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 9: 876870. doi:10.3389/fspas.2022.876870. Bibcode: 2022FrASS...9.6870R.

External links

- RNA World website Link collection (structures, sequences, tools, journals)

- Nucleic Acid Database Images of DNA, RNA and complexes.

- Anna Marie Pyle's Seminar: RNA Structure, Function, and Recognition

|