Biology:Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase

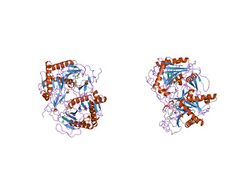

Generic protein structure example |

| Galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase, N-terminal domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | GalP_UDP_transf | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01087 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0265 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00108 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1hxp / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase, C-terminal domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

structure of nucleotidyltransferase complexed with udp-galactose | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | GalP_UDP_tr_C | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02744 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0265 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR005850 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00108 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1hxp / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (or GALT, G1PUT) is an enzyme (EC 2.7.7.12) responsible for converting ingested galactose to glucose.[1]

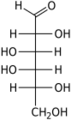

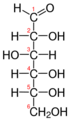

Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) catalyzes the second step of the Leloir pathway of galactose metabolism, namely:

- UDP-glucose + galactose 1-phosphate [math]\displaystyle{ \rightleftharpoons }[/math] glucose 1-phosphate + UDP-galactose

The expression of GALT is controlled by the actions of the FOXO3 gene. The absence of this enzyme results in classic galactosemia in humans and can be fatal in the newborn period if lactose is not removed from the diet. The pathophysiology of galactosemia has not been clearly defined.[1]

Mechanism

GALT catalyzes the second reaction of the Leloir pathway of galactose metabolism through ping pong bi-bi kinetics with a double displacement mechanism.[2] This means that the net reaction consists of two reactants and two products (see the reaction above) and it proceeds by the following mechanism: the enzyme reacts with one substrate to generate one product and a modified enzyme, which goes on to react with the second substrate to make the second product while regenerating the original enzyme.[3] In the case of GALT, the His166 residue acts as a potent nucleophile to facilitate transfer of a nucleotide between UDP-hexoses and hexose-1-phosphates.[4]

- UDP-glucose + E-His ⇌ Glucose-1-phosphate + E-His-UMP

- Galactose-1-phosphate + E-His-UMP ⇌ UDP-galactose + E-His[4]

Structural studies

The three-dimensional structure at 180 pm resolution (x-ray crystallography) of GALT was determined by Wedekind, Frey, and Rayment, and their structural analysis found key amino acids essential for GALT function.[4] Among these are Leu4, Phe75, Asn77, Asp78, Phe79, and Val108, which are consistent with residues that have been implicated both in point mutation experiments as well as in clinical screening that play a role in human galactosemia.[4][6]

GALT also has minimal (~0.1%) GalNAc transferase activity. X-ray crystallography revealed that the side chain of Tyr289 forms a hydrogen bond with the N-acetyl group of UDP-GalNAc. Point mutation of residue Tyr289 to Leu, Ile, or Asn eliminates this interaction, enhancing GalNAc transferase activity, with the Y289L mutation showing comparable GalNAc transferase activity as the wild-type enzyme's Gal transferase activity.[7]

Clinical significance

Deficiency of GALT causes classic galactosemia. Galactosemia is an autosomal recessive inherited disorder detectable in newborns and childhood.[8] It occurs at approximately 1 in every 40,000-60,000 live-born infants. Classical galactosemia (G/G) is caused by a deficiency in GALT activity, whereas the more common clinical manifestations, Duarte (D/D) and the Duarte/Classical variant (D/G) are caused by the attenuation of GALT activity.[9] Symptoms include ovarian failure, developmental coordination disorder (difficulty speaking correctly and consistently),[10] and neurologic deficits.[9] A single mutation in any of several base pairs can lead to deficiency in GALT activity.[11] For example, a single mutation from A to G in exon 6 of the GALT gene changes Glu188 to an arginine and a mutation from A to G in exon 10 converts Asn314 to an aspartic acid.[9] These two mutations also add new restriction enzyme cut sites, which enable detection by and large-scale population screening with PCR (polymerase chain reaction).[9] Screening has mostly eliminated neonatal death by G/G galactosemia, but the disease, due to GALT’s role in the biochemical metabolism of ingested galactose (which is toxic when accumulated) to the energetically useful glucose, can certainly be fatal.[8][12] However, those afflicted with galactosemia can live relatively normal lives by avoiding milk products and anything else containing galactose (because it cannot be metabolized), but there is still the potential for problems in neurological development or other complications, even in those who avoid galactose.[13]

Disease database

Galactosemia (GALT) Mutation Database

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Entrez Gene: GALT galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=2592.

- ↑ "Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase: rate studies confirming a uridylyl-enzyme intermediate on the catalytic pathway". Biochemistry 13 (19): 3889–94. September 1974. doi:10.1021/bi00716a011. PMID 4606575.

- ↑ "Double displacement mechanism - Definition". http://www.mondofacto.com/facts/dictionary?double+displacement+mechanism.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Three-dimensional structure of galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase from Escherichia coli at 1.8 A resolution". Biochemistry 34 (35): 11049–61. September 1995. doi:10.1021/bi00035a010. PMID 7669762.

- ↑ "Untitled Document". http://web.virginia.edu/Heidi/chapter19/chp19frameset.htm.

- ↑ "Identification of mutations in the galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) gene in 16 Turkish patients with galactosemia, including a novel mutation of F294Y. Mutation in brief no. 235. Online". Human Mutation 13 (4): 339. 1999. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:4<339::AID-HUMU18>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 10220154.

- ↑ Ramakrishnan, Boopathy; Qasba, Pradman K. (2002-06-07). "Structure-based Design of β1,4-Galactosyltransferase I (β4Gal-T1) with Equally Efficient N-Acetylgalactosaminyltransferase Activity: POINT MUTATION BROADENS β4Gal-T1 DONOR SPECIFICITY*" (in en). Journal of Biological Chemistry 277 (23): 20833–20839. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111183200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 11916963.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Galactosemia: the good, the bad, and the unknown". Journal of Cellular Physiology 209 (3): 701–5. December 2006. doi:10.1002/jcp.20820. PMID 17001680.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "A molecular approach to galactosemia". European Journal of Pediatrics 154 (7 Suppl 2): S21-7. 1995. doi:10.1007/BF02143798. PMID 7671959.

- ↑ "Apraxia of Speech". http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/voice/apraxia.htm.

- ↑ "Analysis of common mutations in the galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase gene: new assays to increase the sensitivity and specificity of newborn screening for galactosemia". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 5 (1): 42–7. February 2003. doi:10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60450-3. PMID 12552079.

- ↑ "Galactose toxicity in animals". IUBMB Life 61 (11): 1063–74. November 2009. doi:10.1002/iub.262. PMID 19859980.

- ↑ "Galactosemia - Treatment". http://www.umm.edu/ency/article/000366trt.htm.

Further reading

- "Genetic basis of galactosemia". Human Mutation 1 (3): 190–6. 1993. doi:10.1002/humu.1380010303. PMID 1301925.

- "Classical galactosemia and mutations at the galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT) gene". Human Mutation 13 (6): 417–30. 1999. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:6<417::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 10408771.

- "Characterization of two missense mutations in human galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase: different molecular mechanisms for galactosemia". Genomics 12 (3): 596–600. March 1992. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(92)90453-Y. PMID 1373122.

- "The human galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase gene". Genomics 14 (2): 474–80. October 1992. doi:10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80244-7. PMID 1427861.

- "Molecular characterization of two galactosemia mutations and one polymorphism: implications for structure-function analysis of human galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase". Biochemistry 31 (24): 5430–3. June 1992. doi:10.1021/bi00139a002. PMID 1610789.

- "Molecular characterization of two galactosemia mutations: correlation of mutations with highly conserved domains in galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase". American Journal of Human Genetics 49 (4): 860–7. October 1991. PMID 1897530.

- "Molecular basis of galactosemia: mutations and polymorphisms in the gene encoding human galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88 (7): 2633–7. April 1991. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.7.2633. PMID 2011574. Bibcode: 1991PNAS...88.2633R.

- "Sequence of a cDNA encoding human galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase". Molecular Biology & Medicine 7 (4): 365–9. August 1990. PMID 2233247.

- "Cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding human galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase". Molecular Biology & Medicine 5 (2): 107–22. April 1988. PMID 2840550.

- "A new variant of galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase in man: the Los Angeles variant". Annals of Human Genetics 37 (1): 1–8. July 1973. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.1973.tb01808.x. PMID 4759900.

- "Gene dosage studies supporting localization of the structural gene for galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT) to band p13 of chromosome 9". American Journal of Medical Genetics 19 (3): 539–43. November 1984. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320190316. PMID 6095663.

- "Molecular characterization of galactosemia (type 1) mutations in Japanese". Human Mutation 6 (1): 36–43. 1995. doi:10.1002/humu.1380060108. PMID 7550229.

- "A molecular approach to galactosemia". European Journal of Pediatrics 154 (7 Suppl 2): S21-7. 1995. doi:10.1007/BF02143798. PMID 7671959.

- "Galactosemia: a strategy to identify new biochemical phenotypes and molecular genotypes". American Journal of Human Genetics 56 (3): 630–9. March 1995. PMID 7887416.

- "Identification and functional analysis of three distinct mutations in the human galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase gene associated with galactosemia in a single family". American Journal of Human Genetics 56 (3): 640–6. March 1995. PMID 7887417.

- "Regulatory effects of galactose on galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase activity on human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells". FEBS Letters 354 (2): 232–6. November 1994. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(94)01133-8. PMID 7957929.

- "On the molecular nature of the Duarte variant of galactose-1-phosphate uridyl transferase (GALT)". Human Genetics 93 (2): 167–9. February 1994. doi:10.1007/BF00210604. PMID 8112740.

- "A common mutation associated with the Duarte galactosemia allele". American Journal of Human Genetics 54 (6): 1030–6. June 1994. PMID 8198125.

- "Molecular characterization of the H319Q galactosemia mutation". Human Molecular Genetics 2 (3): 325–6. March 1993. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.3.325. PMID 8499924.

External links

- Galactose-1-P-Uridyltransferase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Galactosemia

- Galactosemia (GALT) Mutation Database

- GALT Protein Database

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase

|