Astronomy:SpaceX Mars program

This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. (November 2022) |

The SpaceX Mars program is a set of projects through which the aerospace company SpaceX hopes to facilitate the colonization of Mars. The company claims that this is necessary for the long-term survival of the human species and that its Mars program, including the ongoing development of the SpaceX Starship, will reduce space transportation costs, thereby making travel to Mars a more realistic possibility.

Elon Musk, who founded SpaceX, first presented his goal of enabling Mars colonization in 2001 as a member of the Mars Society's board of directors. In the 2000s and early 2010s, SpaceX made many vehicle concepts for delivering payloads and crews to Mars, including space tugs, heavy-lift launch vehicles, and Red Dragon capsules. The company's current Mars plan was first formally proposed at the 2016 International Astronautical Congress alongside a fully-reusable launch vehicle, the Interplanetary Transport System. Since then, the launch vehicle proposal was altered and renamed to "Starship", and has been in development since. The company has given many estimates of dates of the first human landing on Mars.

SpaceX plans for early missions to Mars to involve small fleets of Starship spacecraft, funded by public–private partnerships. The company hopes that once infrastructure is established on Mars and the launch cost is reduced further, colonization can begin.

The program has been criticized as impractical, both because of uncertainties regarding its financing[1] and because it only addresses transportation to Mars and not the problem of sustaining human life there.

Background

Growth of private spaceflight

Before founding SpaceX, Musk joined the Mars Society's board of directors for a short time. He was offered a plenary talk at their convention where he announced Mars Oasis, a project to land a miniature experimental greenhouse and grow plants on Mars, to revive public interest in space exploration.[2] Musk initially attempted to acquire a Dnepr ICBM for the project through Russian contacts from Jim Cantrell.[3] Russian officials were unreceptive to Musk's approach and on the flight back from Moscow, Musk worked on a spreadsheet and concluded that they could build their own rockets.[4] Over time, Musk's goal evolved from a small publicity mission to generate interest in going to Mars, to a full-scale effort to create an architecture that would enable a self-sustaining human settlement on Mars.[5] This led to the formation of SpaceX.[6]: 30–31

Reusable launch system

Tenets

As early as 2007, Elon Musk stated a personal goal of eventually enabling human exploration and settlement of Mars,[7] although his personal public interest in Mars goes back at least to 2001 at the Mars Society.[6]: 30–31 SpaceX has stated its goal is to colonize Mars to ensure the long-term survival of the human species.[1]

Starship's reusability is expected to reduce launch costs, expanding space access to more payloads and entities.[8] According to Robert Zubrin, aerospace engineer and advocate for human exploration of Mars, Starship's lower launch cost would make space-based economy, colonization, and mining practical.[6]: 25, 26 Lower cost to space may potentially make space research profitable, allowing major advancements in medicine, computers, material science, and more.[6]: 47, 48 Musk has stated that a Starship orbital launch will cost less than $2 million. Pierre Lionnet, director of research at Eurospace, claimed otherwise, citing the rocket's multi-billion-dollar development cost and its current lack of external demand.[9]

Launch vehicle

Starship is designed to be a fully reusable and orbital rocket, aiming to drastically reduce launch costs and maintenance between flights.[10]: 2 The rocket consists of a Super Heavy first stage booster and a Starship second stage spacecraft,[11] powered by Raptor and Raptor Vacuum engines.[12] Both the rocket stages' body are made from stainless steel, giving Starship its shine and strength for atmospheric entry.[13]

Methane was chosen for the Raptor engines because it is relatively cheap, produces low amount of soot as compared to other hydrocarbons,[14] and can be created on Mars from carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and hydrogen via the Sabatier reaction.[15] The engine family uses a new alloy for the main combustion chamber, allowing it to contain 300 bar (4,400 psi) of pressure, the highest of all current engines.[14] In the future, it may be mass-produced[14] and cost about $230,000 per engine or $100 per kilonewton.[16]

Starship is the launch vehicle's second stage and will serve as a long-duration spacecraft on some missions.[17] The spacecraft is 50 m (160 ft) tall[18] and has a dry mass of less than 100 t (220,000 lb).[16] Starship's payload volume is about 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft),[19] larger than the International Space Station's pressurized volume by 80 m3 (2,800 cu ft),[20] and can be even bigger with an extended 22 m (72 ft)-tall volume.[21]: 2 By refueling the Starship spacecraft in orbit using tanker spacecraft, Starship will be able to transport larger payloads and more astronauts to other Earth orbits, to the Moon (Starship HLS), and Mars.[21]: 5

Program manifest

SpaceX plans to build a crewed base on Mars for an extended surface presence, which it hopes will grow into a self-sufficient colony.[22][23] A successful colonization, meaning an established human presence on Mars growing over many decades, would ultimately involve many more economic actors than SpaceX.[24][25][26] Musk has made many tentative predictions about the date of Starship's first Mars landing,[13] including 2029.[27]

Exploration

Musk plans for the first crewed Mars missions to have approximately 12 people, with the goals of "build[ing] out and troubleshoot[ing] the propellant plant and Mars Base Alpha power system" and establishing a "rudimentary base." He has claimed that, in the event of an emergency during travel, the spaceship would be able to safely return to Earth.[28] The company plans to process resources on Mars into fuel for return journeys,[29] and use similar technologies on Earth to create carbon-neutral propellant.[30]

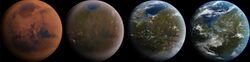

Colonization and terraforming

The program aims to send a million people to Mars, using a thousand Starships sent during a Mars launch window.[31] Proposed journeys would require 80 to 150 days of transit time,[26] with averaging approximately 115 days (for the nine synodic periods occurring between 2020 and 2037).[32]

Prior launch vehicle proposals

Early heavy-lift concepts

In November 2005,[33] before SpaceX launched the Falcon 1, its first rocket,[34] CEO Elon Musk first referenced a long-term and high-capacity rocket concept named BFR. The BFR would be able to launch 100 t (220,000 lb) to low Earth orbit and equipped with Merlin 2 engines. The Merlin 2 is in direct lineage to the Merlin engines used in the Falcon 9 and comparable to the F-1 engines used in the Saturn V.[33]

In July 2010,[35] after the final launch of Falcon 1 a year prior,[36] SpaceX presented launch vehicle and Mars space tug concepts at a conference. The launch vehicle concepts were called Falcon X, Falcon X Heavy, and Falcon XX; the largest of all is the Falcon XX with a 140 t (310,000 lb) capacity to low Earth orbit. To deliver such payload, the rocket was going to be as tall as the Saturn V and use six powerful Merlin 2 engines.[35] Around 2012,[37] the company first mentioned the Mars Colonial Transporter rocket concept in public. It was going to be able to carry 100 people or 100 t (220,000 lb) of cargo to Mars and powered by methane-fueled Raptor engines.[38]

Red Dragon capsule

Interplanetary Transport System

On 26 September 2016, a day before the 67th International Astronautical Congress, the Raptor engine fired for the first time.[39] At the event, Musk announced SpaceX was developing a new rocket using Raptor engines called the Interplanetary Transport System. It would have two stages, a reusable booster and spacecraft. The stages' tanks were to be made from carbon composite, storing liquid methane and liquid oxygen. Despite the rocket's 300 t (660,000 lb) launch capacity to low Earth orbit, it was expected to have a low launch price. The spacecraft featured three variants: crew, cargo, and tanker; the tanker variant is used to transfer propellant to spacecraft in orbit.[40] The concept, especially the technological feats required to make such a system possible and the funds needed, garnered a large amount of skepticism.[41]

Big Falcon Rocket

In September 2017, at the 68th Annual International Astronautical Congress, Musk announced the BFR (Big Falcon Rocket),[42] a revision to the Interplanetary Transport System's design. The rocket was still going to be reusable, but its launch capacity to low Earth orbit was reduced to 150 t (330,000 lb), and its body was smaller. Unlike its conceptual predecessor, the potential applications for the BFR were more varied. Variants of the BFR would be able to send satellites to orbit, resupply the International Space Station, land on the Moon, travel between spaceports on Earth, and ferry crew to Mars.[43] In April 2018, the Mayor of Los Angeles confirmed plan for a BFR rocket production facility at the Port of Los Angeles,[44] but it was cancelled around May 2020.[45]

A year later in September 2018, Musk updated about the spacecraft's new two forward flaps at the top and three larger aft flaps at the bottom. Both set of flaps help control the spacecraft's descent, and the aft flaps are used as landing legs for the final touchdown.[46] Two months later in November 2018, the rocket booster was first termed Super Heavy and the spacecraft was termed Starship.[42]

Development

Uncrewed flight tests

Starship's development is iterative and incremental, marked by tests on rocket prototypes.[47][13] The first prototype to fly using a Raptor engine was called Starhopper.[48] The vehicle had three non-retractable legs and was shorter than the final spacecraft design.[49] The craft performed two tethered hops in early April 2019 and three months later, it hopped without a tether to around 25 m (80 ft).[50] In August 2019, the vehicle hopped to 150 m (500 ft) and traveled to a landing pad nearby.[51]

Mk1 was destroyed November 2019 during a pressure stress test and Mk2 did not fly because the Florida facility was deconstructed throughout 2020.[52][53] SpaceX began naming its new Starship upper-stage prototypes with the prefix "SN", short for "serial number".[47] No prototypes between SN1 and SN4 flew; SN1 and SN3 collapsed during pressure stress tests and SN4 exploded after its fifth engine firing.[54] Starship SN5 was built with no flaps or nose cone, giving it a cylindrical shape. The test vehicle consisted of one Raptor engine, propellant tanks, and a mass simulator. On 5 August 2020, SN5 performed a 150 m (500 ft)-high flight, successfully landing on a nearby pad.[55] On 3 September 2020, the similar-looking Starship SN6 successfully repeated the hop.[56]

SN8 was the first complete Starship prototype and underwent four static fire tests between October and November 2020.[54] On 9 December 2020, SN8 flew, slowly turning off its three engines one by one, and reaching to an altitude of 12.5 km (7.8 mi). The craft then performed the belly-flop maneuver and dove back through the atmosphere. As it tried to land, an issue with fuel tank pressure caused the prototype to lose thrust and impact the pad.[57] On 2 February 2021, Starship SN9 launched to 10 km (6.2 mi) and crashed on landing, similar to SN8.[58]

A month later, on 3 March 2021, Starship SN10 launched on the same flight path and landed hard, crushing its landing legs[59] and exploded, probably due to a propellant tank rupture.[59] Starship SN11, on 30 March 2021, flew into thick fog along the same flight path. During descent, the vehicle exploded, scattering debris up to 8 km (5 mi) away.[60] Starship prototypes SN12, SN13, and SN14 were scrapped before completion, and Starship SN15 was selected to fly instead.[61] The prototype features general improvement on its avionics, structure, and engines, incorporating prior prototype's failures.[62] On 5 May 2021, SN15 launched, completed the same maneuvers as older prototypes, and landed softly[61] after six minutes.[62]

In July 2021, Super Heavy BN3 conducted its first full-duration static firing, lighting three engines.[63] A month later, using cranes, Starship SN20 was stacked atop Super Heavy BN4 for the first time. SN20 was the first to include a body-tall heat shield, made of hexagonal heat tiles.[64] In October 2021, the catching mechanical arms were installed onto the integration tower, and the first tank farm's construction was completed.[65]

Planned launches

On April 20th 2023, SpaceX attempted the first Starship orbital test flight.[66] The rocket lifted off the pad at Starbase in Texas at 8:32 on Thursday 4/20, the rocket hovered on the pad for 8 seconds, sending debris flying. At lift off the rocket became the most powerful rocket ever flown, upon lifting off the pad the rocket had lost 3 of the 33 raptor engines. As the rocket rose through the atmosphere 3 more raptor engines were lost. Around 31km and two and a half minutes into the flight the rocket began to tumble midair. The rocket was unable to recover from this tumble and the flight termination system was activated, ending the inaugural test flight.[67]: 2–4

Reception and feasibility

SpaceX has not detailed plans for the spacecraft's life-support systems, radiation protection, and in situ resource utilization, technologies which are essential for space colonization.[68]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chang, Kenneth (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/28/science/elon-musk-spacex-mars-exploration.html.

- ↑ Elon Musk (30 May 2009). "Risky Business". IEEE Spectrum. https://spectrum.ieee.org/aerospace/space-flight/risky-business.

- ↑ Keith Cowing (30 August 2001). "Millionaires and billionaires: the secret to sending humans to Mars?". SPACEREF. http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewnews.html?id=383.

- ↑ Ball, Molly; Kluger, Jeffrey; de la Garza, Alejandro (13 December 2021). "Elon Musk: Person of the Year 2021". Time (magazine). https://time.com/person-of-the-year-2021-elon-musk/. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ↑ Bierend, Doug (17 July 2014). "SpaceX Was Born Because Elon Musk Wanted to Grow Plants on Mars". Vice. https://www.vice.com/en/article/jp5g8k/spacex-is-because-elon-musk-wanted-to-grow-plants-on-mars.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Zubrin, Robert (14 May 2019). The Case for Space: How the Revolution in Spaceflight Opens Up a Future of Limitless Possibility. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-63388-534-9. OCLC 1053572666.

- ↑ Hoffman, Carl (2007-05-22). "Elon Musk Is Betting His Fortune on a Mission Beyond Earth's Orbit". Wired Magazine. https://www.wired.com/science/space/magazine/15-06/ff_space_musk?currentPage=all.

- ↑ Mann, Adam (20 May 2020). "SpaceX now dominates rocket flight, bringing big benefits—and risks—to NASA" (in en). Science. doi:10.1126/science.abc9093. https://www.science.org/content/article/spacex-now-dominates-rocket-flight-bringing-big-benefits-and-risks-nasa. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ↑ Bender, Maddie (16 September 2021). "SpaceX's Starship Could Rocket-Boost Research in Space" (in en). Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/spacexs-starship-could-rocket-boost-research-in-space/.

- ↑ Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (24 August 2021). "SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship)". Game Changing Development Annual Program Review 2021. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20210020835. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (6 August 2021). "Biggest ever rocket is assembled briefly in Texas". BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-58120874.

- ↑ Ryan, Jackson (21 October 2021). "SpaceX Starship Raptor vacuum engine fired for the first time". https://www.cnet.com/science/spacex-starship-raptor-vacuum-engine-fired-for-the-first-time/.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Chang, Kenneth (Sep 28, 2019). "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/28/science/elon-musk-spacex-starship.html.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 O'Callaghan, Jonathan (31 July 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". https://www.wired.co.uk/article/spacex-raptor-engine-starship.

- ↑ Sommerlad, Joe (28 May 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/space/elon-musk-starship-sn16-mars-b1855721.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ↑ Petrova, Magdalena (13 March 2022). "Why Starship is the holy grail for SpaceX". https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/13/why-starship-is-the-holy-grail-for-spacex.html.

- ↑ Dvorsky, George (6 August 2021). "SpaceX Starship Stacking Produces the Tallest Rocket Ever Built". https://gizmodo.com/spacex-starship-stacking-produces-the-tallest-rocket-ev-1847438954.

- ↑ O'Callaghan, Jonathan (7 December 2021). "How SpaceX's massive Starship rocket might unlock the solar system—and beyond". MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/12/07/1041420/spacex-starship-rocket-solar-system-exploration/.

- ↑ Garcia, Mark (5 November 2021). "International Space Station Facts and Figures". http://www.nasa.gov/feature/facts-and-figures.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Starship Users Guide". March 2020. https://www.spacex.com/media/starship_users_guide_v1.pdf.

- ↑ "SpaceX wants to use the first Mars-bound BFR spaceships as Martian habitats" . Eric Ralph, TeslaRati. August 27, 2018.

- ↑ "We're going to Mars by 2024 if Elon Musk has anything to say about it" . Elizabeth Rayne, SyFy Wire. August 15, 2018.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (2016-09-28). "Musk's Mars moment: Audacity, madness, brilliance—or maybe all three". Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/science/2016/09/musks-mars-moment-audacity-madness-brilliance-or-maybe-all-three/.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (2016-10-10). "Can Elon Musk get to Mars?". SpaceNews. http://www.spacenewsmag.com/feature/can-elon-musk-get-to-mars/.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Boyle, Alan (September 27, 2016). "SpaceX's Elon Musk makes the big pitch for his decades-long plan to colonize Mars". GeekWire. http://www.geekwire.com/2016/spacex-elon-musk-colonize-mars/.

- ↑ Torchinsky, Rina (17 March 2022). "Elon Musk hints at a crewed mission to Mars in 2029" (in en). NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/03/17/1087167893/elon-musk-mars-2029.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (2016-10-23). "SpaceX's Elon Musk geeks out over Mars interplanetary transport plan on Reddit". GeekWire. http://www.geekwire.com/2016/spacex-elon-musk-geeks-out-mars-reddit/.

- ↑ Sommerlad, Joe (28 May 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft" (in en). The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/space/elon-musk-starship-sn16-mars-b1855721.html.

- ↑ Killelea, Eric (16 December 2021). "Musk looks to Earth's atmosphere as source of rocket fuel" (in en-US). https://www.expressnews.com/business/article/Elon-Musk-SpaceX-rocket-fuel-16707544.php.

- ↑ Kooser, Amanda (16 January 2020). "Elon Musk breaks down the Starship numbers for a million-person SpaceX Mars colony" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/elon-musk-drops-details-for-spacexs-million-person-mars-mega-colony/.

- ↑ "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species". SpaceX. 2016-09-27. http://www.spacex.com/sites/spacex/files/mars_presentation.pdf.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Foust, Jeff (14 November 2005). "Big plans for SpaceX". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/497/1.

- ↑ "SpaceX rocket fails first flight" (in en-GB). BBC News. 24 March 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4698736.stm.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Norris, Guy (5 August 2010). "SpaceX Unveils Heavy-Lift Vehicle Plan For Future Exploration". https://aviationweek.com/spacex-unveils-heavy-lift-vehicle-plan-future-exploration.

- ↑ Spudis, Paul D. (22 July 2012). "The Tale of Falcon 1" (in en). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/the-tale-of-falcon-1-5193845/.

- ↑ Coppinger, Rob (23 November 2012). "Huge Mars Colony Eyed by SpaceX Founder Elon Musk" (in en). https://www.space.com/18596-mars-colony-spacex-elon-musk.html.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (29 December 2015). "Speculation mounts over Elon Musk's plan for SpaceX's Mars Colonial Transporter" (in en-US). https://www.geekwire.com/2015/speculation-mounts-over-elon-musks-plans-for-spacexs-mars-colonial-transporter/.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (26 September 2016). "SpaceX performs first test of Raptor engine" (in en-US). SpaceNews. https://spacenews.com/spacex-performs-first-test-of-raptor-engine/.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (27 September 2016). "SpaceX's Mars plans call for massive 42-engine reusable rocket" (in en-US). https://spacenews.com/spacex-unveils-mars-mission-plans/.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond" (in en-US). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/28/science/elon-musk-spacex-mars-exploration.html.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Elon Musk renames his BFR spacecraft Starship" (in en-GB). BBC News. 20 November 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-46274158.

- ↑ Boyle, Alan (29 September 2017). "Elon Musk's updated vision for Mars also shoots for the moon and much, much more" (in en-US). https://www.geekwire.com/2017/elon-musks-updated-vision-mars-also-shoots-moon-much/.

- ↑ Masunaga, Samantha (16 April 2018). "SpaceX will build BFR spaceships and rocket boosters at Port of Los Angeles" (in en-US). https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-spacex-bfr-20180416-story.html.

- ↑ Masunaga, Samantha (8 June 2020). "SpaceX scraps its plan to build Mars spaceship at Port of L.A. — again" (in en-US). https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2020-06-08/spacex-exits-port-of-la-lease-again.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (18 September 2018). "SpaceX signs up Japanese billionaire for circumlunar BFR flight" (in en-US). SpaceNews. https://spacenews.com/spacex-signs-up-japanese-billionaire-for-circumlunar-bfr-flight/.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Berger, Eric (2020-02-21). "SpaceX pushing iterative design process, accepting failure to go fast" (in en-us). https://arstechnica.com/science/2020/02/elon-musk-says-spacex-driving-toward-orbital-starship-flight-in-2020/.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (28 August 2019). "Starhopper aces test, sets up full-scale prototype flights this year" (in en-us). Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/08/starhopper-aces-test-sets-up-full-scale-prototype-flights-this-year/.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (3 April 2019). "SpaceX just fired up the engine on its test Starship vehicle for the first time" (in en). https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/3/18271547/spacex-starship-starhopper-raptor-engine-ignition-hop-static-fire-test.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (26 July 2019). "SpaceX's Starship prototype has taken flight for the first time" (in en-us). Ars Technica. https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/07/spacexs-starship-prototype-has-taken-flight-for-the-first-time/.

- ↑ Harwood, William (27 August 2019). "SpaceX launches "Starhopper" on dramatic test flight" (in en-US). CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/spacex-launches-starhopper-dramatic-test-flight-today-2019-08-27/.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (20 November 2019). "SpaceX's prototype Starship rocket partially bursts during testing in Texas" (in en). The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/11/20/20974884/spacex-starship-rocket-prototype-failure-test-texas.

- ↑ Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities" (in en-US). NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/04/new-permits-spacex-cidco-roberts/.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Kanayama, Lee; Beil, Adrian (28 August 2021). "SpaceX continues forward progress with Starship on Starhopper anniversary" (in en-US). https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/08/starship-starhopper/.

- ↑ Mack, Eric (4 August 2020). "SpaceX Starship prototype takes big step toward Mars with first tiny 'hop'" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/spacex-starship-prototype-takes-big-step-toward-mars-tuesday-with-first-hop/.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (3 September 2020). "SpaceX launches and lands another Starship prototype, the second flight test in under a month" (in en). CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/03/spacex-launches-and-lands-starship-sn6-prototype-in-flight-test.html.

- ↑ Wattles, Jackie (10 December 2020). "Space X's Mars prototype rocket exploded yesterday. Here's what happened on the flight". CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/10/tech/spacex-starship-sn8-test-flight-recap-scn/index.html.

- ↑ Mack, Eric (2 February 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN9 flies high, explodes on landing just like SN8" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/spacex-starship-sn9-rocket-flies-high-explodes-on-landing-just-like-sn8/.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Chang, Kenneth (3 March 2021). "SpaceX Mars Rocket Prototype Explodes, but This Time It Lands First" (in en-US). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/03/science/spacex-starship-launch-sn10.html.

- ↑ Mack, Eric (30 March 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN11 test flight flies high and explodes in the fog" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/spacex-starship-sn11-test-flight-flies-high-tuesday-then-explodes/.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Mack, Eric (7 May 2021). "SpaceX's Mars prototype rocket, Starship SN15, might fly again soon" (in en). CNET. https://www.cnet.com/news/spacexs-mars-prototype-rocket-starship-sn15-might-fly-again-soon/.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Foust, Jeff (5 May 2021). "Starship survives test flight" (in en-US). https://spacenews.com/starship-survives-test-flight/.

- ↑ Berger, Eric (23 July 2021). "Rocket Report: Super Heavy lights up, China tries to recover a fairing" (in en-us). https://arstechnica.com/science/2021/07/rocket-report-super-heavy-lights-up-china-tries-to-recover-a-fairing/.

- ↑ Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2021). "Musk: 'Dream come true' to see fully stacked SpaceX Starship rocket during prep for orbital launch" (in en). CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/06/elon-musk-spacex-starship-fully-stacked-is-dream-come-true.html.

- ↑ Weber, Ryan (31 October 2021). "Major elements of Starship Orbital Launch Pad in place as launch readiness draws nearer" (in en-US). NASASpaceFlight.com. https://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2021/10/starship-orbital-launch-pad/.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (13 June 2022). "FAA requiring SpaceX to make changes to Texas launch site ahead of future launches" (in en). https://www.theverge.com/2022/6/13/22994460/spacex-faa-starbase-boca-chica-texas-environmental-review-mitigated-fonsi.

- ↑ "Starship Orbital – First Flight FCC Exhibit". SpaceX. 13 May 2021. https://apps.fcc.gov/els/GetAtt.html?id=273481.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (4 October 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival" (in en). https://www.theverge.com/2019/10/4/20895056/elon-musk-starship-spacex-human-health-life-support-radiation.

External links