Medicine:Hepatitis A

| Hepatitis A | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Infectious hepatitis |

| |

| A case of jaundice caused by hepatitis A | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease, gastroenterology |

| Symptoms | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dark urine, jaundice, fever, abdominal pain[1] |

| Complications | Acute liver failure[1] |

| Usual onset | 2–6 weeks after infection[2] |

| Duration | 8 weeks[1] |

| Causes | Eating food or drinking water contaminated with Hepatovirus A infected feces[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests[1] |

| Prevention | Hepatitis A vaccine, hand washing, properly cooking food[1][3] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, liver transplantation[1] |

| Frequency | 114 million symptomatic and nonsymptomatic (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 11,200[5] |

Hepatitis A is an infectious disease of the liver caused by Hepatovirus A (HAV);[6] it is a type of viral hepatitis.[7] Many cases have few or no symptoms, especially in the young.[1] The time between infection and symptoms, in those who develop them, is 2–6 weeks.[2] When symptoms occur, they typically last 8 weeks and may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, fever, and abdominal pain.[1] Around 10–15% of people experience a recurrence of symptoms during the 6 months after the initial infection.[1] Acute liver failure may rarely occur, with this being more common in the elderly.[1]

It is usually spread by eating food or drinking water contaminated with infected feces.[1] Undercooked or raw shellfish are relatively common sources.[8] It may also be spread through close contact with an infectious person.[1] While children often do not have symptoms when infected, they are still able to infect others.[1] After a single infection, a person is immune for the rest of their life.[9] Diagnosis requires blood testing, as the symptoms are similar to those of a number of other diseases.[1] It is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E.

The hepatitis A vaccine is effective for prevention.[1][3][needs update] Some countries recommend it routinely for children and those at higher risk who have not previously been vaccinated.[1][10] It appears to be effective for life.[1] Other preventive measures include hand washing and properly cooking food.[1] No specific treatment is available, with rest and medications for nausea or diarrhea recommended on an as-needed basis.[1] Infections usually resolve completely and without ongoing liver disease.[1] Treatment of acute liver failure, if it occurs, is with liver transplantation.[1]

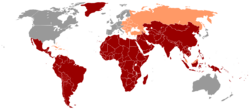

Globally, around 1.4 million symptomatic cases occur each year[1] and about 114 million infections (symptomatic and asymptomatic).[4] It is more common in regions of the world with poor sanitation and not enough safe water.[10] In the developing world, about 90% of children have been infected by age 10, thus are immune by adulthood.[10] It often occurs in outbreaks in moderately developed countries where children are not exposed when young and vaccination is not widespread.[10] Acute hepatitis A resulted in 11,200 deaths in 2015.[5] World Hepatitis Day occurs each year on July 28 to bring awareness to viral hepatitis.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Early symptoms of hepatitis A infection can be mistaken for influenza, but some people, especially children, exhibit no symptoms at all. Symptoms typically appear 2–6 weeks (the incubation period) after the initial infection.[11] About 90% of children do not have symptoms. The time between infection and symptoms, in those who develop them, is 2–6 weeks, with an average of 28 days.[2]

The risk for symptomatic infection is directly related to age, with more than 80% of adults having symptoms compatible with acute viral hepatitis and the majority of children having either asymptomatic or unrecognized infections.[12]

Symptoms usually last less than 2 months, although some people can be ill for as long as 6 months:[13]

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Nausea

- Appetite loss

- Jaundice, a yellowing of the skin or the whites of the eyes owing to hyperbilirubinemia

- Bile is removed from the bloodstream and excreted in the urine, giving it a dark amber color

- Diarrhea

- Light or clay-colored faeces (acholic faeces)

- Abdominal discomfort[14]

Extrahepatic manifestations

Joint pains, red cell aplasia, pancreatitis and generalized lymphadenopathy are the possible extrahepatic manifestations. Kidney failure and pericarditis are very uncommon.[15] If they occur, they show an acute onset and disappear upon resolution of the disease.[citation needed]

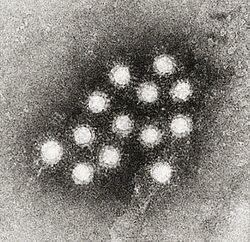

Virology

| Hepatovirus A | |

|---|---|

| |

| Electron micrograph of Hepatovirus A virions | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Picornavirales |

| Family: | Picornaviridae |

| Genus: | Hepatovirus |

| Species: | Hepatovirus A

|

| Synonyms | |

Taxonomy

Hepatovirus A is a species of virus in the order Picornavirales, family Picornaviridae, genus Hepatovirus. Humans and other vertebrates serve as natural hosts.[18][19]

Nine members of Hepatovirus are recognized.[20] These species infect bats, rodents, hedgehogs, and shrews. Phylogenetic analysis suggests a rodent origin for Hepatitis A.[citation needed]

A member virus of hepatovirus B (Phopivirus) has been isolated from a seal.[21][22] This virus shared a common ancestor with Hepatovirus A about 1800 years ago.[citation needed]

Another hepatovirus – Marmota himalayana hepatovirus – has been isolated from the woodchuck Marmota himalayana.[23] This virus appears to have had a common ancestor with the primate-infecting species around 1000 years ago.[citation needed]

Genotypes

One serotype and seven different genetic groups (four human and three simian) have been described.[24] The human genotypes are numbered I–III. Six subtypes have been described (IA, IB, IIA, IIB, IIIA, IIIB). The simian genotypes have been numbered IV–VI. A single isolate of genotype VII isolated from a human has also been described.[25] Genotype III has been isolated from both humans and owl monkeys. Most human isolates are of genotype I.[26] Of the type I isolates subtype IA accounts for the majority.

The mutation rate in the genome has been estimated to be 1.73–9.76 × 10−4 nucleotide substitutions per site per year.[27][28] The human strains appear to have diverged from the simian about 3600 years ago.[28] The mean age of genotypes III and IIIA strains has been estimated to be 592 and 202 years, respectively.[28]

Structure

Hepatovirus A is a picornavirus; it is not enveloped and contains a positive-sense, single-strand of RNA packaged in a protein shell.[24] Only one serotype of the virus has been found, but multiple genotypes exist.[29] Codon use within the genome is biased and unusually distinct from its host. It also has a poor internal ribosome entry site.[30] In the region that codes for the HAV capsid, highly conserved clusters of rare codons restrict antigenic variability.[18][31]

| Genus | Structure | Symmetry | Capsid | Genomic arrangement | Genomic segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatovirus | Icosahedral | Pseudo T=3 | Nonenveloped | Linear | Monopartite |

Replication cycle

Vertebrates such as humans serve as the natural hosts. Transmission routes are fecal-oral and blood.[18]

Following ingestion, HAV enters the bloodstream through the epithelium of the oropharynx or intestine.[32] The blood carries the virus to its target, the liver, where it multiplies within hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (liver macrophages). Viral replication is cytoplasmic. Entry into the host cell is achieved by attachment of the virus to host receptors, which mediates endocytosis. Replication follows the positive-stranded RNA virus replication model. Translation takes place by viral initiation. The virus exits the host cell by lysis and viroporins. Virions are secreted into the bile and released in stool. HAV is excreted in large numbers about 11 days prior to the appearance of symptoms or anti-HAV IgM antibodies in the blood. The incubation period is 15–50 days and risk of death in those infected is less than 0.5%.[citation needed]

Within the liver hepatocytes, the RNA genome is released from the protein coat and is translated by the cell's own ribosomes. Unlike other picornaviruses, this virus requires an intact eukaryotic initiation factor 4G (eIF4G) for the initiation of translation.[33] The requirement for this factor results in an inability to shut down host protein synthesis, unlike other picornaviruses. The virus must then inefficiently compete for the cellular translational machinery, which may explain its poor growth in cell culture. Aragonès et al. (2010) theorize that the virus has evolved a naturally highly deoptimized codon usage with respect to that of its cellular host in order to negatively influence viral protein translation kinetics and allow time for capsid proteins to fold optimally.[33]

No apparent virus-mediated cytotoxicity occurs, presumably because of the virus' own requirement for an intact eIF4G, and liver pathology is likely immune-mediated.

| Genus | Host details | Tissue tropism | Entry details | Release details | Replication site | Assembly site | Transmission |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatovirus | Humans; vertebrates | Liver | Cell receptor endocytosis | Lysis | Cytoplasm | Cytoplasm | Oral-fecal; blood |

Transmission

The virus spreads by the fecal–oral route, and infections often occur in conditions of poor sanitation and overcrowding. Hepatitis A can be transmitted by the parenteral route, but very rarely by blood and blood products. Food-borne outbreaks are common,[34] and ingestion of shellfish cultivated in polluted water is associated with a high risk of infection.[35] About 40% of all acute viral hepatitis is caused by HAV.[32] Infected individuals are infectious prior to onset of symptoms, roughly 10 days following infection. The virus is resistant to detergent, acid (pH 1), solvents (e.g., ether, chloroform), drying, and temperatures up to 60 °C. It can survive for months in fresh and salt water. Common-source (e.g., water, restaurant) outbreaks are typical. Infection is common in children in developing countries, reaching 100% incidence, but following infection, lifelong immunity results. HAV can be inactivated by chlorine treatment (drinking water), formalin (0.35%, 37 °C, 72 hours), peracetic acid (2%, 4 hours), beta-propiolactone (0.25%, 1 hour), and UV radiation (2 μW/cm2/min). HAV can also be spread through sexual contact specifically oroanal sexual acts.[citation needed]

In developing countries, and in regions with poor hygiene standards, the rates of infection with this virus are high[36] and the illness is usually contracted in early childhood. As incomes rise and access to clean water increases, the incidence of HAV decreases.[37] In developed countries, though, the infection is contracted primarily by susceptible young adults, most of whom are infected with the virus during trips to countries with a high incidence of the disease[2] or through contact with infectious persons.

Humans are the only natural reservoir of the virus. No known insect or other animal vectors can transmit the virus. A chronic HAV state has not been reported.[38]

Diagnosis

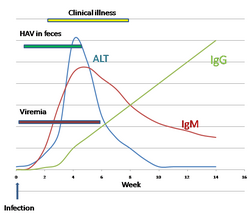

Although HAV is excreted in the feces towards the end of the incubation period, specific diagnosis is made by the detection of HAV-specific IgM antibodies in the blood.[39] IgM antibody is only present in the blood following an acute hepatitis A infection. It is detectable from 1–2 weeks after the initial infection and persists for up to 14 weeks. The presence of IgG antibodies in the blood means the acute stage of the illness has passed and the person is immune to further infection. IgG antibodies to HAV are also found in the blood following vaccination, and tests for immunity to the virus are based on the detection of these antibodies.[39]

During the acute stage of the infection, the liver enzyme alanine transferase (ALT) is present in the blood at levels much higher than is normal. The enzyme comes from the liver cells damaged by the virus.[40]

Hepatovirus A is present in the blood (viremia) and feces of infected people up to 2 weeks before clinical illness develops.[40]

Prevention

Hepatitis A can be prevented by vaccination, good hygiene, and sanitation.[6][41]

Vaccination

The two types of vaccines contain either inactivated Hepatovirus A or a live but attenuated virus.[3] Both provide active immunity against a future infection. The vaccine protects against HAV in more than 95% of cases for longer than 25 years.[42] In the United States, the vaccine developed by Maurice Hilleman and his team was licensed in 1995,[43][44] and the vaccine was first used in 1996 for children in high-risk areas, and in 1999 it was spread to areas with elevating levels of infection.[45]

The vaccine is given by injection. An initial dose provides protection lasting one year starting 2–4 weeks after vaccination; the second booster dose, given six to 12 months later, provides protection for over 20 years.[45]

The vaccine was introduced in 1992 and was initially recommended for persons at high risk. Since then, Bahrain and Israel have embarked on elimination programmes.[46] In countries where widespread vaccination has been practised, the incidence of hepatitis A has decreased dramatically.[47][48][49][50]

In the United States, vaccination of children is recommended at 1 and 2 years of age;[1] hepatitis A vaccination is not recommended in those younger than 12 months of age.[51] It is also recommended in those who have not been previously immunized and who have been exposed or are likely to be exposed due to travel.[1] The CDC recommends vaccination against infection for men who have sex with men.[52]

Treatment

No specific treatment for hepatitis A is known. Recovery from symptoms following infection may take several weeks or months. Therapy is aimed at maintaining comfort and adequate nutritional balance, including replacement of fluids lost from vomiting and diarrhea.[14]

Prognosis

In the United States in 1991, the mortality rate for hepatitis A was estimated to be 0.015% for the general population, but ranged up to 1.8–2.1% for those aged 50 and over who were hospitalized with icteric hepatitis.[53] The risk of death from acute liver failure following HAV infection increases with age and when the person has underlying chronic liver disease.[citation needed]

Young children who are infected with hepatitis A typically have a milder form of the disease, usually lasting 1–3 weeks, whereas adults tend to experience a much more severe form of the disease.[34]

Epidemiology

Globally, symptomatic HAV infections are believed to occur in around 1.4 million people a year.[1] About 114 million infections (asymptomatic and symptomatic) occurred all together in 2015.[4] Acute hepatitis A resulted in 11,200 deaths in 2015.[5] Developed countries have low circulating levels of hepatovirus A, while developing countries have higher levels of circulation.[54] Most adolescents and adults in developing countries have already had the disease, thus are immune.[54] Adults in midlevel countries may be at risk of disease with the potential of being exposed.[54]

Countries

Over 30,000 cases of hepatitis A were reported to the CDC in the US in 1997, but the number has since dropped to less than 2,000 cases reported per year.[55]

The most widespread hepatitis A outbreak in the United States occurred in 2018, in the state of Kentucky. The outbreak is believed to have started in November 2017.[56] By July 2018 48% of the state's counties had reported at least one case of hepatitis A, and the total number of suspected cases was 969 with six deaths (482 cases in Louisville, Kentucky).[57] By July 2019 the outbreak had reached 5,000 cases and 60 deaths, but had slowed to just a few new cases per month.[56]

Another widespread outbreak in the United States, the 2003 US hepatitis outbreak, affected at least 640 people (killing four) in northeastern Ohio and southwestern Pennsylvania in late 2003. The outbreak was blamed on tainted green onions at a restaurant in Monaca, Pennsylvania.[58][59] In 1988, more than 300,000 people in Shanghai, China, were infected with HAV after eating clams (Anadara subcrenata) from a contaminated river.[32] In June 2013, frozen berries sold by US retailer Costco and purchased by around 240,000 people were the subject of a recall, after at least 158 people were infected with HAV, 69 of whom were hospitalized.[60][61] In April 2016, frozen berries sold by Costco were once again the subject of a recall, after at least 13 people in Canada were infected with HAV, three of whom were hospitalized.[62] In Australia in February 2015, a recall of frozen berries was issued after at least 19 people contracted the illness following their consumption of the product.[63] In 2017, California (particularly around San Diego), Michigan, and Utah reported outbreaks of hepatitis A that have led to over 800 hospitalizations and 40 deaths.[64][65][66]

See also

- 2019 United States hepatitis A outbreak

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 Matheny, SC; Kingery, JE (1 December 2012). "Hepatitis A.". Am Fam Physician 86 (11): 1027–34; quiz 1010–1012. PMID 23198670. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1201/p1027.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Connor BA (2005). "Hepatitis A vaccine in the last-minute traveler". Am. J. Med. 118 (Suppl 10A): 58S–62S. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.018. PMID 16271543.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Hepatitis A immunisation in persons not previously exposed to hepatitis A.". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7 (7): CD009051. 2012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009051.pub2. PMID 22786522.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 ((GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators)) (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 ((GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators)) (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. 2004. pp. 541–4. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ "Hepatitis MedlinePlus". https://medlineplus.gov/hepatitis.html.

- ↑ Bellou, M.; Kokkinos, P.; Vantarakis, A. (March 2013). "Shellfish-borne viral outbreaks: a systematic review.". Food Environ Virol 5 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1007/s12560-012-9097-6. PMID 23412719.

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Hepatitis and Other Liver Diseases. Infobase. 2006. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8160-6990-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=HfPU99jIfboC&pg=PA105.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Hepatitis A Fact sheet N°328". World Health Organization. July 2013. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs328/en/.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Symptoms". eMedicineHealth. 2007-05-17. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/hepatitis_a/page3_em.htm#Hepatitis%20A%20Symptoms.

- ↑ Ciocca M. (2000). "Clinical course and consequences of hepatitis A infection". Vaccine 18: 71–4. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00470-3. PMID 10683554.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Information for the Public". Center for Disease Control. 2009-09-17. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/A/aFAQ.htm.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Hepatitis A". https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs328/en/.

- ↑ Mauss, Stefan; Berg, Thomas; Rockstroh, Juergen; Sarrazin, Christoph (2012). Hepatology: A clinical textbook. Germany: Flying publisher. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-3-924774-73-8.

- ↑ Knowles, Nick (7 July 2014). "Rename12 Picornavirus species" (in en). https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/2014.016aV.A.v1.Picornaviridae_spren.pdf.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 van Regenmortel, M.H.V., Fauquet, C.M., Bishop, D.H.L., Carstens, E.B., Estes, M.K., Lemon, S.M., Maniloff, J., Mayo, M.A., McGeoch, D.J., Pringle, C.R. and Wickner, R.B. (2000). Virus taxonomy. Seventh report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego. p672 https://ictv.global/ictv/proposals/ICTV%207th%20Report.pdf.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Viral Zone". ExPASy. http://viralzone.expasy.org/all_by_species/94.html.

- ↑ ICTV. "Virus Taxonomy: 2014 Release". http://ictvonline.org/virusTaxonomy.asp.

- ↑ "Virus Taxonomy: 2019 Release". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. https://ictv.global/taxonomy.

- ↑ "Discovery of a novel hepatovirus (Phopivirus of seals) related to human hepatitis A virus". mBio 6 (4): e01180–15. 2015. doi:10.1128/mBio.01180-15. PMID 26307166.

- ↑ "Genus: Hepatovirus" (in en). https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/positive-sense-rna-viruses/picornavirales/w/picornaviridae/709/genus-hepatovirus.

- ↑ "A novel hepatovirus identified in wild woodchuck Marmota himalayana". Sci Rep 6: 22361. 2016. doi:10.1038/srep22361. PMID 26924426. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...622361Y.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Genetic variability and molecular evolution of hepatitis A virus". Virus Res. 127 (2): 151–7. August 2007. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.005. PMID 17328982.

- ↑ "Genetic characterization of wild-type genotype VII hepatitis A virus". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 1): 53–60. January 2002. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-83-1-53. PMID 11752700.

- ↑ "Characterization of hepatitis A virus isolates from subgenotypes IA and IB in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil". J. Med. Virol. 66 (1): 22–7. January 2002. doi:10.1002/jmv.2106. PMID 11748654.

- ↑ "Bayesian coalescent inference of hepatitis A virus populations: evolutionary rates and patterns". J. Gen. Virol. 88 (Pt 11): 3039–42. November 2007. doi:10.1099/vir.0.83038-0. PMID 17947528.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "Full length genomes of genotype IIIA Hepatitis A Virus strains (1995–2008) from India and estimates of the evolutionary rates and ages". Infect. Genet. Evol. 9 (6): 1287–94. December 2009. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.08.009. PMID 19723592.

- ↑ "Genetic variability of hepatitis A virus". J. Gen. Virol. 84 (Pt 12): 3191–201. December 2003. doi:10.1099/vir.0.19532-0. PMID 14645901.

- ↑ "Low efficiency of the 5' nontranslated region of hepatitis A virus RNA in directing cap-independent translation in permissive monkey kidney cells". J. Virol. 68 (8): 5253–63. August 1994. doi:10.1128/JVI.68.8.5253-5263.1994. PMID 8035522.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A virus mutant spectra under the selective pressure of monoclonal antibodies: codon usage constraints limit capsid variability". J. Virol. 82 (4): 1688–700. February 2008. doi:10.1128/JVI.01842-07. PMID 18057242.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Murray, P.R., Rosenthal, K.S. & Pfaller, M.A. (2005). Medical Microbiology 5th ed., Elsevier Mosby.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Andino, Raul, ed (March 2010). "Fine-tuning translation kinetics selection as the driving force of codon usage bias in the hepatitis A virus capsid". PLOS Pathog. 6 (3): e1000797. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000797. PMID 20221432.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Hepatitis A". Am Fam Physician 73 (12): 2162–8. 2006. PMID 16848078. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0615/p2162.html.

- ↑ Lees D (2000). "Viruses and bivalve shellfish". Int. J. Food Microbiol. 59 (1–2): 81–116. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(00)00248-8. PMID 10946842.

- ↑ Steffen R (October 2005). "Changing travel-related global epidemiology of hepatitis A". Am. J. Med. 118 (Suppl 10A): 46S–49S. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.016. PMID 16271541.

- ↑ "The effects of socioeconomic development on worldwide hepatitis A virus seroprevalence patterns". Int J Epidemiol 34 (3): 600–9. 2005. doi:10.1093/ije/dyi062. PMID 15831565.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015. Web. 25 Oct. 2016.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Stapleton JT (1995). "Host immune response to hepatitis A virus". J. Infect. Dis. 171 (Suppl 1): S9–14. doi:10.1093/infdis/171.Supplement_1.S9. PMID 7876654.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Tests of Liver Injury". Clin Med Res 2 (2): 129–31. 2004. doi:10.3121/cmr.2.2.129. PMID 15931347.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A — Prevention". NHS Choices. National Health Service (England). 21 March 2012. http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Hepatitis-A/Pages/Prevention.aspx?url=Pages/What-is-it.aspx.

- ↑ Nothdurft HD (July 2008). "Hepatitis A vaccines". Expert Rev Vaccines 7 (5): 535–45. doi:10.1586/14760584.7.5.535. PMID 18564009.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A: Vaccine Licensed | History of Vaccines" (in en). https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/hepatitis-vaccine-licensed.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). "Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World". Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 978-0-12-804571-8.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Hepatitis A Vaccine: What you need to know". Vaccine Information Statement. CDC. 2006-03-21. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/downloads/vis-hep-a.pdf.

- ↑ André FE (2006). "Universal mass vaccination against hepatitis A". Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 304: 95–114. doi:10.1007/3-540-36583-4_6. ISBN 978-3-540-29382-8. PMID 16989266.

- ↑ "Changing epidemiology of hepatitis A and hepatitis E in urban and rural India (1982-98)". Journal of Viral Hepatitis 8 (4): 293–303. 21 December 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2893.2001.00279.x. PMID 11454182.

- ↑ Estripeaut, Dora; Contreras, Rodolfo; Tinajeros, Olga; Castrejón, Maria Mercedes; Shafi, Fakrudeen; Ortega-Barria, Eduardo; Deantonio, Rodrigo (22 June 2015). "Impact of Hepatitis A vaccination with a two-dose schedule in Panama: Results of epidemiological surveillance and time trend analysis". Vaccine (Elseiver) 33 (28): 3200–3207. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.100. PMID 25981490.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A surveillance and vaccine use in China from 1990 through 2007". J Epidemiol 19 (4): 189–195. 2009. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20080087. PMID 19561383.

- ↑ "Surveillance for acute viral hepatitis — United States, 2007". MMWR Surveill Summ 58 (3): 1–27. May 2009. PMID 19478727. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss5803.pdf.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Questions and Answers for Health Professionals | Division of Viral Hepatitis | CDC" (in en-us). 2018-07-27. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/havfaq.htm.

- ↑ "Men Who Have Sex with Men | Populations and Settings | Division of Viral Hepatitis | CDC" (in en-us). 31 May 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/populations/msm.htm.

- ↑ "AABB". https://www.aabb.org/tm/eid/Documents/hepatitis-a-virus.pdf.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Jacobsen, KH; Wiersma, ST (24 September 2010). "Hepatitis A virus seroprevalence by age and world region, 1990 and 2005". Vaccine 28 (41): 6653–7. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.037. PMID 20723630.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A Information for Health Professionals — Statistics and Surveillance". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HAV/StatisticsHAV.htm.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Wymer, Garrett (December 11, 2019). "Hepatitis A numbers down in Kentucky; health officials still urge vaccination". WKYT. https://www.wkyt.com/content/news/Hepatitis-A-numbers-down-in-Kentucky-health-officials-still-urge-vaccination-566096281.html.

- ↑ "Officials: Kentucky's hepatitis A outbreak now worst in US". Associated Press. June 28, 2018. http://www.wkyt.com/content/news/Officials-Kentuckys-hepatitis-A-outbreak-now-worst-in-US-486818101.html.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (November 2003). "Hepatitis A outbreak associated with green onions at a restaurant—Monaca, Pennsylvania, 2003". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52 (47): 1155–7. PMID 14647018. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5247.pdf.

- ↑ "An outbreak of hepatitis A associated with green onions". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (9): 890–7. September 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050855. PMID 16135833.

- ↑ Weise, Elizabeth (18 June 2013). "118 sickened in hepatitis A outbreak linked to berries". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/06/18/hepatitis-a-frozen-berries-118-sick/2434267/.

- ↑ "Outbreak Cases". Viral Hepatitis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 October 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Outbreaks/2013/A1b-03-31/index.html.

- ↑ "Recalled Costco frozen berries linked to 13 cases of Hepatitis A". The Canadian Press. 19 April 2016. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/04/19/recalled-costco-frozen-berries-linked-to-13-cases-of-hepatitis-a.html/.

- ↑ "Frozen berries Heptitus A scare". 17 February 2015. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-02-17/fourth-frozen-berry-product-recalled-in-hepatitis-a-scare/6126272.

- ↑ Ramseth, Luke (November 19, 2017). "Utah's hepatitis A outbreak among the homeless is one of three big flare-ups around the country". The Salt Lake Tribune. http://www.sltrib.com/news/health/2017/11/19/utahs-hepatitis-a-outbreak-among-the-homeless-is-one-of-three-big-flare-ups-around-the-country/.

- ↑ "San Diego is struggling with a huge hepatitis A | Word Range" (in en-US). http://wordrange.us/san-diego-is-struggling-with-a-huge-hepatitis-a-outbreak-is-it-coming-to-l-a/.

- ↑ Smith, Joshua Emerson. "Grim conditions in public restrooms hurt fight to halt deadly hepatitis outbreak in San Diego". LA Times. http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-san-diego-hepatitis-restrooms-20170924-story.html.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Wikidata ☰ Q24722353 entry

|