Superscalar processor

A superscalar processor is a CPU that implements a form of parallelism called instruction-level parallelism within a single processor.[1] In contrast to a scalar processor, which can execute at most one single instruction per clock cycle, a superscalar processor can execute more than one instruction during a clock cycle by simultaneously dispatching multiple instructions to different execution units on the processor. It therefore allows more throughput (the number of instructions that can be executed in a unit of time) than would otherwise be possible at a given clock rate. Each execution unit is not a separate processor (or a core if the processor is a multi-core processor), but an execution resource within a single CPU such as an arithmetic logic unit.

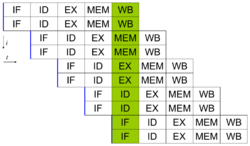

While a superscalar CPU is typically also pipelined, superscalar and pipelining execution are considered different performance enhancement techniques. The former executes multiple instructions in parallel by using multiple execution units, whereas the latter executes multiple instructions in the same execution unit in parallel by dividing the execution unit into different phases.

The superscalar technique is traditionally associated with several identifying characteristics (within a given CPU):

- Instructions are issued from a sequential instruction stream

- The CPU dynamically checks for data dependencies between instructions at run time (versus software checking at compile time)

- The CPU can execute multiple instructions per clock cycle

History

Seymour Cray's CDC 6600 from 1964 is often mentioned as the first superscalar design. The 1967 IBM System/360 Model 91 was another superscalar mainframe. The Intel i960CA (1989),[2] the AMD 29000-series 29050 (1990), and the Motorola MC88110 (1991),[3] microprocessors were the first commercial single-chip superscalar microprocessors. RISC microprocessors like these were the first to have superscalar execution, because RISC architectures free transistors and die area which can be used to include multiple execution units (this was why RISC designs were faster than CISC designs through the 1980s and into the 1990s).

Except for CPUs used in low-power applications, embedded systems, and battery-powered devices, essentially all general-purpose CPUs developed since about 1998 are superscalar.

The P5 Pentium was the first superscalar x86 processor; the Nx586, P6 Pentium Pro and AMD K5 were among the first designs which decode x86-instructions asynchronously into dynamic microcode-like micro-op sequences prior to actual execution on a superscalar microarchitecture; this opened up for dynamic scheduling of buffered partial instructions and enabled more parallelism to be extracted compared to the more rigid methods used in the simpler P5 Pentium; it also simplified speculative execution and allowed higher clock frequencies compared to designs such as the advanced Cyrix 6x86.

Scalar to superscalar

The simplest processors are scalar processors. Each instruction executed by a scalar processor typically manipulates one or two data items at a time. By contrast, each instruction executed by a vector processor operates simultaneously on many data items. An analogy is the difference between scalar and vector arithmetic. A superscalar processor is a mixture of the two. Each instruction processes one data item, but there are multiple execution units within each CPU thus multiple instructions can be processing separate data items concurrently.

Superscalar CPU design emphasizes improving the instruction dispatcher accuracy, and allowing it to keep the multiple execution units in use at all times. This has become increasingly important as the number of units has increased. While early superscalar CPUs would have two ALUs and a single FPU, a later design such as the PowerPC 970 includes four ALUs, two FPUs, and two SIMD units. If the dispatcher is ineffective at keeping all of these units fed with instructions, the performance of the system will be no better than that of a simpler, cheaper design.

A superscalar processor usually sustains an execution rate in excess of one instruction per machine cycle. But merely processing multiple instructions concurrently does not make an architecture superscalar, since pipelined, multiprocessor or multi-core architectures also achieve that, but with different methods.

In a superscalar CPU the dispatcher reads instructions from memory and decides which ones can be run in parallel, dispatching each to one of the several execution units contained inside a single CPU. Therefore, a superscalar processor can be envisioned having multiple parallel pipelines, each of which is processing instructions simultaneously from a single instruction thread.

Limitations

Available performance improvement from superscalar techniques is limited by three key areas:

- The degree of intrinsic parallelism in the instruction stream (instructions requiring the same computational resources from the CPU)

- The complexity and time cost of dependency checking logic and register renaming circuitry

- The branch instruction processing

Existing binary executable programs have varying degrees of intrinsic parallelism. In some cases instructions are not dependent on each other and can be executed simultaneously. In other cases they are inter-dependent: one instruction impacts either resources or results of the other. The instructions a = b + c; d = e + f can be run in parallel because none of the results depend on other calculations. However, the instructions a = b + c; b = e + f might not be runnable in parallel, depending on the order in which the instructions complete while they move through the units.

Although the instruction stream may contain no inter-instruction dependencies, a superscalar CPU must nonetheless check for that possibility, since there is no assurance otherwise and failure to detect a dependency would produce incorrect results.

No matter how advanced the semiconductor process or how fast the switching speed, this places a practical limit on how many instructions can be simultaneously dispatched. While process advances will allow ever greater numbers of execution units (e.g. ALUs), the burden of checking instruction dependencies grows rapidly, as does the complexity of register renaming circuitry to mitigate some dependencies. Collectively the power consumption, complexity and gate delay costs limit the achievable superscalar speedup.

However even given infinitely fast dependency checking logic on an otherwise conventional superscalar CPU, if the instruction stream itself has many dependencies, this would also limit the possible speedup. Thus the degree of intrinsic parallelism in the code stream forms a second limitation.

Alternatives

Collectively, these limits drive investigation into alternative architectural changes such as very long instruction word (VLIW), explicitly parallel instruction computing (EPIC), simultaneous multithreading (SMT), and multi-core computing.

With VLIW, the burdensome task of dependency checking by hardware logic at run time is removed and delegated to the compiler. Explicitly parallel instruction computing (EPIC) is like VLIW with extra cache prefetching instructions.

Simultaneous multithreading (SMT) is a technique for improving the overall efficiency of superscalar processors. SMT permits multiple independent threads of execution to better utilize the resources provided by modern processor architectures.

Superscalar processors differ from multi-core processors in that the several execution units are not entire processors. A single processor is composed of finer-grained execution units such as the ALU, integer multiplier, integer shifter, FPU, etc. There may be multiple versions of each execution unit to enable execution of many instructions in parallel. This differs from a multi-core processor that concurrently processes instructions from multiple threads, one thread per processing unit (called "core"). It also differs from a pipelined processor, where the multiple instructions can concurrently be in various stages of execution, assembly-line fashion.

The various alternative techniques are not mutually exclusive—they can be (and frequently are) combined in a single processor. Thus a multicore CPU is possible where each core is an independent processor containing multiple parallel pipelines, each pipeline being superscalar. Some processors also include vector capability.

See also

- Eager execution

- Hyper-threading

- Simultaneous multithreading

- Out-of-order execution

- Shelving buffer

- Speculative execution

- Software lockout, a multiprocessor issue similar to logic dependencies on superscalars

- Super-threading

References

- ↑ "What is a Superscalar Processor? - Definition from Techopedia" (in en). http://www.techopedia.com/definition/2897/superscalar-processor.

- ↑ McGeady, Steven (Spring 1990). "The i960CA SuperScalar implementation of the 80960 architecture". Digest of Papers Compcon Spring '90. Thirty-Fifth IEEE Computer Society International Conference on Intellectual Leverage. 232–240. doi:10.1109/CMPCON.1990.63681. ISBN 0-8186-2028-5.

- ↑ Diefendorff, K.; Allen, M. (Spring 1992). "The Motorola 88110 Superscalar RISC microprocessor". Digest of Papers COMPCON Spring 1992. 157–162. doi:10.1109/CMPCON.1992.186702. ISBN 0-8186-2655-0.

- Mike Johnson, Superscalar Microprocessor Design, Prentice-Hall, 1991, ISBN:0-13-875634-1

- Sorin Cotofana, Stamatis Vassiliadis, "On the Design Complexity of the Issue Logic of Superscalar Machines", EUROMICRO 1998: 10277-10284

- Steven McGeady, et al., "Performance Enhancements in the Superscalar i960MM Embedded Microprocessor," ACM Proceedings of the 1991 Conference on Computer Architecture (Compcon), 1991, pp. 4–7

External links

- Eager Execution / Dual Path / Multiple Path, By Mark Smotherman

|