Astronomy:Alpheratz

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox (celestial coordinates) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Andromeda |

| Right ascension | 00h 08m 23.25988s[1] |

| Declination | +29° 05′ 25.5520″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 2.06 (2.22 + 4.21)[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| U−B color index | −0.46[3] |

| B−V color index | −0.11[3] |

| R−I color index | −0.10[3] |

| Primary | |

| Spectral type | B8IV-VHgMn[4] |

| Secondary | |

| Spectral type | A3V[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Primary | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −10.6 ± 0.3[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 135.68[7] mas/yr Dec.: −162.95[7] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 33.62 ± 0.35[1] mas |

| Distance | 97 ± 1 ly (29.7 ± 0.3 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −0.19 ± 0.30[8] |

| Secondary | |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 2.00 ± 0.30[8] |

| Orbit[2] | |

| Period (P) | 96.7015 ± 0.0044 days |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 24.0 ± 0.13 mas |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.535 ± 0.0046 |

| Inclination (i) | 105.6 ± 0.23° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 284.4 ± 0.21° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | MJD 47374.563 ± 0.095 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 257.4 ± 0.31° |

| Details | |

| Primary | |

| Mass | 3.8 ± 0.2[9] M☉ |

| Radius | 2.7 ± 0.4[9] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 240[9] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.75[9] cgs |

| Temperature | 13,800[9] K |

| Metallicity | [M/H] = 0.2 |

| Rotation | 2.38195 d[10] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 52 km/s |

| Age | 60[9] Myr |

| Secondary | |

| Mass | 1.85 ± 0.13[9] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.65 ± 0.3[9] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 13[9] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.0[9] cgs |

| Temperature | 8,500[9] K |

| Metallicity | [M/H] = 0.2 |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 110 ± 5 km/s |

| Age | 70[9] Myr |

| Other designations | |

Alpheratz, Sirrah, Sirah, α And, Alpha Andromedae, Alpha And, δ Pegasi, δ Peg, Delta Pegasi, Delta Peg, 21 Andromedae, 21 And, H 5 32A, MKT 11, ADS 94 A, BD+28°4, CCDM J00083+2905A, FK5 1, GC 127, HD 358, HIP 677, HR 15, IDS 00032+2832 A, LTT 10039, NLTT 346, PPM 89441, SAO 73765, WDS 00084+2905A/Aa[7][11][12] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

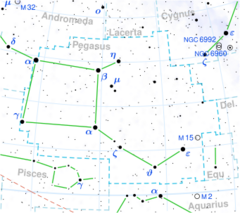

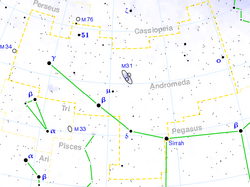

Alpheratz /ælˈfɪəræts/,[13][14] or Alpha Andromedae (α Andromedae, abbreviated Alpha And or α And), is a bright star 97 light-years from the Sun and is the brightest star in the constellation of Andromeda when Beta Andromedae undergoes its periodical dimming. Immediately northeast of the constellation of Pegasus, it is the upper left star of the Great Square of Pegasus.

Although it appears to the naked eye as a single star, with overall apparent visual magnitude +2.06, it is actually a binary system composed of two stars in close orbit. The chemical composition of the brighter of the two stars is unusual as it is a mercury-manganese star whose atmosphere contains abnormally high levels of mercury, manganese, and other elements, including gallium and xenon.[15] It is the brightest mercury-manganese star known.[15]

Nomenclature

α Andromedae (Latinised to Alpha Andromedae) is the star's Bayer designation. Ptolemy considered the star (system) to be shared by Pegasus and Johann Bayer assigned it a designation in both constellations: Alpha Andromedae (α And) and Delta Pegasi (δ Peg). Since the IAU standardized constellation boundaries and widely published them two years after in 1930, the Pegasi alternate name has dropped from use, putting it slightly outside of that constellation.[16]

To most European centres of learning the star bore names Alpheratz (/ælˈfiːræts/[17]) or the cognate simplification Alpherat or the other part of the fabled description: Sirrah /ˈsɪrə/.

The origin of these three, the Arabic phrasal name, is سرة الفرس surrat al-faras "navel of the mare/horse", attracting a hard consonant not present above due to a following vowel. The horse corresponds equivalently to the winged horse of the Greeks, Pegasus. The star is in almost all depictions part of the main asterism of Pegasus and Andromeda.[18] In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[19] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[20] confirmed Alpheratz as the name for the main star.

Other terms for this star used by some medieval astronomers writing were راس المراة المسلسلة rās al-mar'a al-musalsala (head of the woman in chains),[18] al-kaff al-khaḍīb and kaff al-naṣīr (palm of the faithful). The chained woman referenced Andromeda.[21]

In the Hindu lunar zodiac, this star, together with the other stars in the Great Square of Pegasus (α, β, and γ Pegasi), makes up the nakshatras of Pūrva Bhādrapadā and Uttara Bhādrapadā.[18]

In Chinese, 壁宿 (Bì Sù), meaning wall, refers to an asterism consisting of α Andromedae and γ Pegasi.[22] Consequently, the Chinese name for α Andromedae itself is 壁宿二 (Bì Sù èr, English: the second star of the wall.)[23]

It is also known as one of the "Three Guides" that mark the prime meridian of the heavens, the other two being Beta Cassiopeiae and Gamma Pegasi. It was believed to bless those born under its influence with honour and riches.[24]

System

The radial velocity of a star away from or towards the observer can be determined by measuring the red shift or blue shift of its spectrum. The American astronomer Vesto Slipher made a series of such measurements from 1902 to 1904 and discovered that the radial velocity of α Andromedae varied periodically. He concluded that it was in orbit in a spectroscopic binary star system with a period of about 100 days.[25] A preliminary orbit was published by Hans Ludendorff in 1907,[26] and a more precise orbit was later published by Robert Horace Baker.[27]

The fainter star in the system was first resolved interferometrically by Xiaopei Pan and his coworkers during 1988 and 1989, using the Mark III Stellar Interferometer at the Mount Wilson Observatory, California , United States. This work was published in 1992.[28] Because of the difference in luminosity between the two stars, its spectral lines were not observed until the early 1990s, in observations made by Jocelyn Tomkin, Xiaopei Pan, and James K. McCarthy between 1991 and 1994 and published in 1995.[5]

The two stars are now known to orbit each other with a period of 96.7 days.[2] The larger, brighter star, called the primary, has a spectral type of B8IV-VHgMn,[4] a mass of approximately 3.6 solar masses, a surface temperature of about 13,800 K, and, measured over all wavelengths, a luminosity of about 200 times the Sun's. Its smaller, fainter companion, the secondary, has a mass of approximately 1.8 solar masses and a surface temperature of about 8,500 K, and, again measured over all wavelengths, a luminosity of about 10 times the Sun's. It is an early-type A star whose spectral type has been estimated as A3V.[5]

Chemical peculiarities

In 1906, Norman Lockyer and F. E. Baxandall reported that α Andromedae had a number of unusual lines in its spectrum.[29] In 1914, Baxandall pointed out that most of the unusual lines came from manganese, and that similar lines were present in the spectrum of μ Leporis.[30] In 1931, W. W. Morgan identified 12 additional stars with lines from manganese appearing in their spectra.[31] Many of these stars were subsequently identified as part of the group of mercury-manganese stars,[32] a class of chemically peculiar stars which have an excess of elements such as mercury, manganese, phosphorus, and gallium in their atmospheres.[33], §3.4. In the case of α Andromedae, the brighter primary star is a mercury-manganese star which, as well as the elements already mentioned, has excess xenon.

In 1970, Georges Michaud suggested that such chemically peculiar stars arose from radiative diffusion. According to this theory, in stars with unusually calm atmospheres, some elements sink under the force of gravity, while others are pushed to the surface by radiation pressure.[33], §4.[34] This theory has successfully explained many observed chemical peculiarities, including those of mercury-manganese stars.[33], §4.

Variability of primary

α Andromedae has been reported to be slightly variable,[35] but observations from 1990 to 1994 found its brightness to be constant to within less than 0.01 magnitude.[36] However, Adelman and his co-workers have discovered, in observations made between 1993 and 1999 and published in 2002, that the mercury line in its spectrum at 398.4 nm varies as the primary rotates. This is because the distribution of mercury in its atmosphere is not uniform. Applying Doppler imaging to the observations allowed Adelman et al. to find that it was concentrated in clouds near the equator.[37] Subsequent Doppler imaging studies, published in 2007, showed that these clouds drift slowly over the star's surface.[10]

Observation

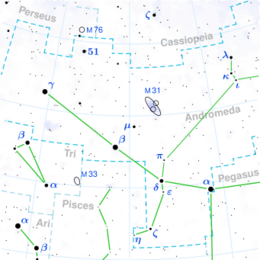

The location of α Andromedae in the sky is shown on the left. It can be seen by the naked eye and is theoretically visible at all latitudes north of 60° S. During evening from August to October, it will be high in the sky as seen from the northern midlatitudes.[38]

Optical companion

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Andromeda |

| Right ascension | 00h 08m 16.626s[39] |

| Declination | +29° 05′ 45.49″[39] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 10.8[39] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G5[39] |

| B−V color index | 1.0[39] |

| Astrometry | |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3.9[39] mas/yr Dec.: −24.0[39] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 2.3990 ± 0.0369[40] mas |

| Distance | 1,360 ± 20 ly (417 ± 6 pc) |

| Position (relative to A) | |

| Epoch of observation | 2000 |

| Angular distance | 89.3″ [11] |

| Position angle | 284° [11] |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

The binary system described above has an optical visual companion, discovered by William Herschel on July 21, 1781.[11][41][42] Designated as ADS 94 B in the Aitken Double Star Catalogue, it is a G-type star with an apparent visual magnitude of approximately 10.8.[39] Although by coincidence it appears near to the other two stars in the sky, it's much more distant from Earth; the parallax observed by Gaia place this star more than 1,300 light years away.[41]

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Entry, WDS identifier 00084+2905, Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars , William I. Hartkopf & Brian D. Mason, U.S. Naval Observatory. Accessed on line August 12, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. Jr.. "HR 15". The Bright Star Catalogue. VizieR. http://webviz.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR-S?HR%2015. and Hoffleit, D.; Warren, W. H. Jr.. "Detailed Description of V/50". The Bright Star Catalogue. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/Cat?V/50.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Simbad - Object view". https://simbad.cds.unistra.fr/mobile/object.html?object_name=HR+15.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tomkin, J.; Pan, X.; McCarthy, J. K. (1995). "Spectroscopic detection of the secondaries of the Hyades interferometric spectroscopic binary theta2 Tauri and of the interferometric spectroscopic binary alpha Andromedae". Astronomical Journal 109: 780. doi:10.1086/117321. Bibcode: 1995AJ....109..780T.

- ↑ Value is for the center of mass of the system.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "* alf And". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=%2A+alf+And.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ryabchikova, T. A.; Malanushenko, V. P.; Adelman, S. J. (1999). "Orbital elements and abundance analyses of the double-lined spectroscopic binary alpha Andromedae". Astronomy and Astrophysics 351: 963. Bibcode: 1999A&A...351..963R.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 Ryabchikova, T.; Malanushenko, V.; Adelman, S. J. (1998). "The double-lined spectroscopic binary alpha Andromedae: Orbital elements and elemental abundances". Contributions of the Astronomical Observatory Skalnate Pleso 27 (3): 356. Bibcode: 1998CoSka..27..356R.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kochukhov, O. (2007). "Weather in stellar atmosphere revealed by the dynamics of mercury clouds in α Andromedae". Nature Physics 3 (8): 526–529. doi:10.1038/nphys648. Bibcode: 2007NatPh...3..526K.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Entry 00084+2905, discoverer code H 5 32, components Aa-B, The Washington Double Star Catalog , United States Naval Observatory. Accessed on line August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Entry 00084+2905, discoverer code MKT 11, components Aa, The Washington Double Star Catalog , United States Naval Observatory. Accessed on line August 15, 2017.

- ↑ Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/IAU-CSN.txt.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Alpheratz, Kaler Stars [1] 2/14/2013

- ↑ Bayer's Uranometria and Bayer letters

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Dictionary 2017 – Alpheratz

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Allen, R. A. (1899). Star-names and Their Meanings. G. E. Stechert. p. 35. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5xQuAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/WGSN_bulletin1.pdf.

- ↑ Goldstein, B. R. (1985). "Star Lists in Hebrew". Centaurus 28 (3): 185–208. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1985.tb00745.x. Bibcode: 1985Cent...28..185G.

- ↑ 陳久金 (2005) (in zh). 台灣書房出版有限公司. p. 170. ISBN 978-986-7332-25-7.

- ↑

"Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in zh). Hong Kong Space Museum. http://www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/Museum/Space/Research/StarName/c_research_chinengstars_ala_alz.htm. - ↑ Olcott, W. T. (1911). Star Lore of All Ages. G.P. Putnam's Sons. p. 26. https://archive.org/details/starloreofallage00olcouoft.

- ↑ Slipher, V. M. (1904). "A list of five stars having variable radial velocities". The Astrophysical Journal 20: 146. doi:10.1086/141148. Bibcode: 1904ApJ....20..146S.

- ↑ Ludendorff, H. (1907). "Provisorische Bahnelemente des spektroskopischen Doppelsterns α Andromedae". Astronomische Nachrichten 176 (20): 327–328. doi:10.1002/asna.19071762007. Bibcode: 1907AN....176..327L. https://zenodo.org/record/1424851.

- ↑ Baker, R. H. (1910). "The orbit of α Andromedae". Publications of the Allegheny Observatory of the Western University of Pennsylvania 1 (3): 17. Bibcode: 1910PAllO...1...17B.

- ↑ Pan, X. (1992). "Determination of the visual orbit of the spectroscopic binary Alpha Andromedae with submilliarcsecond precision". The Astrophysical Journal 384: 624. doi:10.1086/170904. Bibcode: 1992ApJ...384..624P.

- ↑ Lockyer, N.; Baxandall, F. E. (1906). "Some Stars with Peculiar Spectra". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A 77 (520): 550. doi:10.1098/rspa.1906.0049. Bibcode: 1906RSPSA..77..550L.

- ↑ Baxandall, F. E. (1914). "Stars, Spectra of, on the enhanced lines of Manganese in the spectrum of α Andromedae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 74 (3): 250. doi:10.1093/mnras/74.3.250. Bibcode: 1914MNRAS..74..250B.

- ↑ Morgan, W. W. (1931). "Studies in Peculiar Stellar Spectra. I. The Manganese Lines in α Andromedae". The Astrophysical Journal 73: 104. doi:10.1086/143299. Bibcode: 1931ApJ....73..104M.

- ↑ Cowley, C. R.; Aikman, G. C. L. (1975). "A study of the lambda 3984 feature in the mercury-manganese stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 87: 513. doi:10.1086/129801. Bibcode: 1975PASP...87..513C.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Smith, K. C. (1996). "Chemically peculiar hot stars". Astrophysics and Space Science 237 (1–2): 77–105. doi:10.1007/BF02424427. Bibcode: 1996Ap&SS.237...77S.

- ↑ Michaud, G. (1970). "Diffusion Processes in Peculiar a Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 160: 641. doi:10.1086/150459. Bibcode: 1970ApJ...160..641M.

- ↑ "alf And * (entry 019001)". General Catalogue of Variable Stars. Sternberg Astronomical Institute. http://www.sai.msu.su/groups/cluster/gcvs/gcvs/iii/iii.dat.

- ↑ Adelman, S. J. (1994). "uvby photometry of the chemically peculiar stars Alpha Andromedae, HD 184905, HR 8216, and HR 8434". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement 106: 333. Bibcode: 1994A&AS..106..333A.

- ↑ Adelman, S. J. (2002). "The Variability of the Hgiiλ3984 Line of the Mercury-Manganese Star α Andromedae". The Astrophysical Journal 575 (1): 449–460. doi:10.1086/341140. Bibcode: 2002ApJ...575..449A.

- ↑ "Alpheratz". MSN Encarta. http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761587658/Alpheratz.html.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 39.8 "TYC 1735-3181-1". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=TYC+1735-3181-1.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. A. (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 616: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Bibcode: 2018A&A...616A...1G.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Burnham, R. (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook: An Observer's Guide to the Universe Beyond the Solar System. 1. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 111. ISBN 0-486-23567-X.

- ↑ See p.140, entry 32 in Herschel, M.; Watson, D. (1782). "Catalogue of Double Stars. By Mr. Herschel, F. R. S. Communicated by Dr. Watson, Jun". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 72: 112–162. doi:10.1098/rstl.1782.0014. Bibcode: 1782RSPT...72..112H. https://zenodo.org/record/1432266.

External links

Coordinates: ![]() 00h 08m 23.2586s, 29° 05′ 25.555″

00h 08m 23.2586s, 29° 05′ 25.555″

|