Power Architecture

Power Architecture is a registered trademark for similar reduced instruction set computing (RISC) instruction sets for microprocessors developed and manufactured by such companies as IBM, Freescale/NXP, AppliedMicro, LSI, Teledyne e2v and Synopsys. The governing body is Power.org, comprising over 40 companies and organizations.

"Power Architecture" is a broad term including all products based on newer POWER, PowerPC and Cell processors. The term "Power Architecture" should not be confused with IBM's different generations of "POWER Instruction Set Architecture", an earlier instruction set for IBM RISC processors of the 1990s from which the PowerPC instruction set was derived.

Power Architecture is a family name describing processor architecture, software, toolchain, community and end-user appliances and not a strict term describing specific products or technologies.

More details and documentation on the Power Architecture can be found on the IBM Portal for OpenPOWER.

Glossary

There can be misunderstanding of the meaning of the terms, POWER, PowerPC and Power Architecture. The following glossary gives brief descriptions of each term, along with links to articles with details.

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| POWER | Performance Optimization With Enhanced RISC. An old microprocessor instruction set architecture designed by IBM. |

| PowerPC | Power Performance Computing. A 32/64-bit instruction set for microprocessors derived from the POWER ISA, including some new elements. Designed by the AIM alliance; Apple, IBM and Motorola. |

| PowerPC-AS | PowerPC-Advanced Series. Codename "Amazon". A purely 64-bit variant of PowerPC, with the addition of features for the use of the AS/400 software. Used in IBM's RS64 family processors and newer POWER processors. |

| POWERn | Where n is a number from 1 to 9. A series of high-end microprocessors built by IBM using different combinations of POWER, PowerPC, PowerPC-AS and Power instruction sets.

Main articles: POWER processors, POWER1, POWER2, POWER3, POWER4, POWER5, POWER6, POWER7, POWER8 and POWER9 |

| Cell | Cell Broadband Engine Architecture (CBEA), a microprocessor architecture designed by IBM, Sony and Toshiba, which has Power Architecture as a part. |

| Power Architecture | The broad term designating all that is POWER, PowerPC and Cell including software, toolchain and end-user appliances. These are the focus of this article. |

| Power ISA | A new instruction set, combining the PowerPC and PowerPC Book E instruction sets. Designed by IBM and Freescale. |

History

Power Architecture originated at IBM in the late 1980s when that company wanted a high-performance RISC architecture for their mid-range workstations and servers. The result was the "POWER architecture". Its first implementation featured in the RS/6000 computers introduced in 1990. This was the 10-chip RIOS-1 processor, later called POWER1. The RISC Single Chip (RSC) processor was developed from RIOS-1.

In 1992 Apple, IBM and Motorola formed the AIM alliance to develop a mass-market version of the POWER processor. This resulted in the "PowerPC architecture", a modified version of the POWER architecture. The first PowerPC implementation was the PowerPC 601 of 1993. Based heavily on RSC, it found its way into Apple's Power Mac computers as well as into IBM RS/6000 systems. The differences between the POWER instruction set and PowerPC is outlined in Appendix E of the manual for PowerPC ISA v.2.02.[1]

IBM expanded their POWER architecture for their RS/6000 systems, which resulted in the eight-chip POWER2 processor in 1993 and in a single-chip version called P2SC, "POWER2 Super Chip", in 1996.

In the early 1990s IBM sought to replace its CISC-based AS/400 minicomputers with a RISC architecture. This new architecture, developed under the code name "Amazon", came to be referred to as the PowerPC-AS ("Advanced Series" or "Amazon Series") amongst engineers working on the project. PowerPC-AS was to be a multi-processor server platform based on RSC. As development continued at IBM Research labs to extend RSC to support a 64-processor inter-connect and to add features specific to AS/400, RS/6000 developers joined in and added some POWER2 features. It all ended up with the 64-bit A10 and A30 processors introduced in 1995 and with the later RS64 line in 1997, used in AS/400 and RS/6000 systems.

The AIM Alliance continued to develop PowerPC from 1995 through 1997 and released the second-generation PowerPC processors: The PowerPC 602 for set-top boxes and game consoles; the PowerPC 603 geared towards the embedded market and portable computers; the PowerPC 604 for workstations; and PowerPC 620, a 64-bit high-performance processor for servers. The 602 and 620 never found widespread use, but the 603, 604 and their successors became very popular in their respective fields. Motorola and IBM also made the "Book E"[2] extension of PowerPC, used in embedded implementations: Motorola's PowerQUICC processors and IBM's PowerPC 400 family.

The last effort of the AIM Alliance was the third generation PowerPC 750 in 1997. Motorola and IBM went their separate ways in developing the PowerPC architecture after that. The PowerPC 750 processors found widespread use in both computer and embedded markets and IBM kept evolving the 750 family in the years to come. Motorola, however, chose to focus on the embedded market with PowerPC SoC designs and the PowerPC 7400, which they called the fourth generation PowerPC. This processor incorporated AltiVec, a SIMD unit. The PowerPC 7400 came in 1999 and was used by Apple in workstations and laptops and by various companies in the telecom market.

In 1998 came POWER3, which unified the PowerPC and POWER2 architectures but was only used in IBM's RS/6000 servers.

2000 saw the last implementation of the PowerPC-AS architecture, the RS64-IV, used in the AS/400 and in the RS/6000, now renamed the eServer iSeries and the eServer pSeries respectively. IBM also produced the Gekko processor - based on the PowerPC 750CXe - for use in Nintendo's GameCube game console. IBM built the Rivina, experimental 64-bit PowerPC processor, which became the first microprocessor to surpass the 1 GHz mark.

In 2001 IBM introduced the POWER4, which unified and replaced the PowerPC-AS and POWER3 architectures.

In 2002 Apple needed a new high-end PowerPC part and got IBM to make the 64-bit PowerPC 970 and Apple described it as the fifth-generation PowerPC or "G5". The PowerPC 970 derives from POWER4. It lacks some server-oriented features, but does have an AltiVec unit. The 970 and its descendants are used by Apple and IBM and some high-end embedded applications.

In 2003 Tundra Semiconductor bought the PowerPC 100 family of microcontrollers from Motorola, while Culturecom licensed PowerPC technology from IBM for their V-Dragon processor.

Motorola spun off its semiconductor division into a new company called Freescale Semiconductor in 2004, while IBM introduced POWER5, an evolution from POWER4. It bumped the PowerPC specification to v.2.01,[3] and again to v.2.02[4] in 2005 with the POWER5+. AMCC during 2004 licensed IP and staff from IBM concerning the PowerPC 400 family.[5] Motorola/Freescale renamed its PowerPC families to e200, e300, e500 and e600 and announced the future 64-bit e700. In 2004 IBM and 15 other companies founded Power.org as an organization with the mission of developing products revolving around the Power Architecture and with the purpose of developing, enabling and promoting Power Architecture technology.[6]

2005 saw the specifications of the Cell processor,[7] jointly developed by IBM, Sony and Toshiba over a four-year period. Its primary use is for Sony's PlayStation 3. Cell uses a single 64-bit Power Architecture core, and adds 8 independent SIMD cores called SPEs. IBM also revealed the Xenon processor, a tri-core 64-bit processor for use in Microsoft's Xbox 360. With the 32-bit PowerPC based Broadway processor that Nintendo would use for its Wii console, IBM had put Power Architecture processors in all three of the major seventh-generation game consoles.

P.A. Semi licensed[when?] Power Architecture technology from IBM for use in its PWRficient processors.

Freescale joined Power.org in 2006 and IBM made the specifications of PowerPC 405 freely available to researchers and to academia.

Power.org released the Power ISA version 2.03.[8] in September 2006. All previous PowerPC specifications are compatible with the 64-bit Power ISA. This added, among other things, VMX, virtualization and variable-length encoding (VLE, 2-byte instructions added to previously 4-byte instructions) to the specification.

Power.org released the Power Architecture Platform Reference, PAPR, in the fourth quarter of 2006. It provided the foundation for development of computers based on Power Architecture-based using the Linux operating system.

In April 2007, Freescale and IPextreme opened up a licensing program for Freescale's PowerPC e200 core.[9] In May 2007 IBM launched its POWER6 high-end microprocessor with speeds up to 5.0 GHz, doubling the performance of the previous POWER5. The POWER6 added AltiVec to the POWER series and an FPU supporting decimal arithmetic. The same day AMCC announced its Titan high-end embedded processor, reaching 2 GHz while consuming very little power. It uses innovative logic design from Intrinsity and would become available in 2008. The members of Power.org finalized the Power ISA v.2.04[10] specification in June 2007. Improvements focused mainly on server applications and virtualization. At the Power Architecture Developer Conference in September 2007, drafts to Power ISA v.2.05 and ePAPR specification were shown, and a Linux-based reference design based on PowerPC 970MP was revealed.[11] The Power ISA v.2.05 specification was released in December 2007.[12]

In April 2008, IBM rebranded their Power Architecture-based hardware, System p and System i. They are now called "Power Systems". At the same time IBM rebranded the i5/OS operating system as "IBM i". On May 25, 2008, IBM became the first vendor to break the 1 Petaflops barrier with the Roadrunner supercomputer.[13] In June 2008 Roadrunner entered the Top500 list of the fastest computers in the world in first place, replacing the BlueGene/L which had held that position since November 2004. On June 16, 2008, Freescale announced QorIQ families P1, P2, P3, P4 and P5, the evolution of PowerQUICC, featuring the eight-core P4080.[14]

According to the June 2008 TOP500 list, the third- and sixth-fastest supercomputers in the world, and 22 of the 50 fastest supercomputers, used IBM's technologies based on Power Architecture. Of the top ten, five used Power Architecture processors as computing elements and one used them as communications processors.

In September 2008, a new supercomputer, Blue Waters, originally intended to be POWER7-based, got the green light.[15] For a cost of $208 million, it will contain 200,000 processors, bringing multi-petaflops performance in 2010-2011. In December 2008, the ePAPR v.1.0 specification for embedded computers based on Power Architecture was finalized.[16] In 2011 IBM dropped out of the project;[17] Cray Research provided the actual processors used.[18]

The Power ISA v.2.06 specification was released in February 2009, and revised in July 2010.[19] Mentor Graphics enables the Android mobile operating system on Freescale's QorIQ and PowerQUICC III platforms in July 2009.[20]

At the ISSCC 2010 conference in February 2010 IBM released the POWER7 processor and revealed the A2 "wire-speed processor" - both massively multicore and multithreaded server-oriented processors comprising over 1 billion transistors each. In June Freescale announced their first 64-bit core, the e5500, implemented in the QorIQ P5 family processors.[21]

Freescale announced the multithreaded 64-bit e6500 core in June 2011 under the QorIQ AMP brand. It will reintroduce AltiVec SIMD units into Freescale's offerings, and be integrated in multiple products manufactured in a 28 nm process beginning 2012.[22]

At the E3 trade show in June 2011 Nintendo announced the Wii U game console, which uses a multicore Power Architecture processor of unknown characteristics, designed and manufactured by IBM.[23]

In August 2013 IBM founded the OpenPOWER Foundation, an initiative to spur innovation and collaboration in the server and data-center space, opening up for licensing of their future POWER8 processor and related technologies. They also revealed the POWER8 processor itself, manufactured on a 22 nm process, with 12 eight-way multithreaded cores running at 4 GHz.

IBM released servers based on POWER8 in June 2014.[24] Tyan, a founding member of the OpenPOWER Foundation, released the first third-party POWER8 based hardware in October 2014.[25] Suzhou PowerCore, a Chinese company, released CP1, the first POWER8 derived processor, in late 2015.[26][27]

The OpenPOWER Foundation released the Power ISA version 3.0 in December 2015. Among a great number of changes and additions it removes the different server and embedded categories and adds support for future processors while keeping backward compatibility.[28]

Licensing

The Power Architecture is open for licensing by third parties. Licensees can choose to license anything from a single predefined core, to a complete new family of Power Architecture products. [citation needed]

IBM licenses hard (predefined chip designs) and soft (synthesized design that can be used in different foundries) core implementations of both the 32-bit and 64-bit Power Architecture, either directly or through Power Design Center partners such as HCL Technologies or Synopsys[citation needed]. On a strategic basis, IBM also provide both microarchitecture and architecture licenses. A microarchitecture license enables licensees to implement a new pipeline for a core, but not to add or subtract instructions from the Power Instruction Set Architecture (ISA). Microarchitecture licenses cover both 64-bit and 32-bit, although individual licenses are available if necessary/desired.

IBM has announced plans to make the specifications of the PowerPC 405 core freely available to the academic and research community.

In April 2007 Freescale and IPextreme opened up the PowerPC e200 cores for licensing to other manufacturers.[9]

Companies that have developed or are developing their own processors based on the Power Architecture under license include Tundra Semiconductor, Applied Micro Circuits Corporation, HCL Enterprise, Culturecom, P.A. Semi, Xilinx, Microsoft, Rapport, Sony, Honeywell, Toshiba and Cray.

Description

| Designer | Power.org |

|---|---|

| Bits | 32-bit/64-bit (32 → 64) |

| Introduced | 2006 |

| Version | 3.0 |

| Design | RISC |

| Type | Register-Register |

| Encoding | Fixed/Variable |

| Branching | Condition code |

| Endianness | Big/Bi |

| Extensions | AltiVec, APU, DSP, CBEA |

| Open | Yes |

| Registers | |

| |

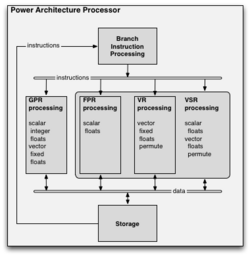

The instruction set architecture is divided into several categories and every component is defined as a part of a category; each category resides within a certain Book. Processors implement a set of these categories. Different classes of processors are required to implement certain categories, for example a server class processor includes the categories Base, Server, Floating-Point, 64-Bit, etc. All processors implement the Base category.

Power is a RISC load/store architecture. It has multiple sets of registers:

- thirty-two 32-bit or 64-bit general purpose registers (GPRs) for integer operations.

- sixty-four 128-bit vector scalar registers (VSRs) for vector operations and floating point operations.

- thirty-two 64-bit floating-point registers (FPRs) as part of the VSRs for floating point operations.

- thirty-two 128-bit vector registers (VRs) as part of the VSRs for vector operations.

- Eight 4-bit condition register fields (CRs) for comparison and control flow.

- Special registers: counter register (CTR), link register (LR), time base (TBU, TBL), alternate time base (ATBU, ATBL), accumulator (ACC), status registers (XER, FPSCR, VSCR, SPEFSCR).

Instructions have a length of 32 bits, with the exception of the VLE (variable-length encoding) subset that provides for higher code density for low-end embedded applications. Most instructions are triadic, i.e. have two source operands and one destination. Single and double precision IEEE-754 compliant floating point operations are supported, including additional fused multiply–add (FMA) and decimal floating-point instructions. There are provisions for SIMD operations on integer and floating point data on up to 16 elements in a single instruction.

Support for Harvard cache, i.e. split data and instruction caches, as well as support for unified caches. Memory operations are strictly load/store, but allow for out-of-order execution. Support for both big and little-endian addressing with separate categories for moded and per-page endianness. Support for both 32-bit and 64-bit addressing.

Different modes of operation include user, supervisor and hypervisor.

Categories

- Base – Most of Book I and Book II

- Server – Book III-S

- Embedded – Book III-E

- Misc – floating point, vector, signal processing, cache locking, decimal floating point, etc.

Books

The Power Architecture specification is divided into five parts, called "books":

- Book I – User Instruction Set Architecture covers the base instruction set available to the application programmer. Memory reference, flow control, Integer, floating point, numeric acceleration, application-level programming. It includes chapters regarding auxiliary processing units like DSPs and the AltiVec extension.

- Book II – Virtual Environment Architecture defines the storage model available to the application programmer, including timing, synchronization, cache management, storage features, byte ordering.

- Book III – Operating Environment Architecture includes exceptions, interrupts, memory management, debug facilities and special control functions. It's divided into two parts.

- Book III-S – Defines the supervisor instructions used for general purpose/server implementations. It is mainly the contents of the Book III of the former PowerPC ISA.

- Book III-E – Defines the supervisor instructions used for embedded applications. It is derived from the former PowerPC Book E.

- Book VLE – Variable Length Encoded Instruction Architecture defines alternative instructions and definitions from Book I-III, intended for higher instruction density and very-low-end applications. They use 16-bit instructions and big endian byte ordering.

Specifications

Power ISA v.2.03

The specification for Power ISA v.2.03[8] is based on the former PowerPC ISA v.2.02[4] in POWER5+ and the Book E[2] extension of the PowerPC specification. The Book I included five new chapters regarding auxiliary processing units like DSPs and the AltiVec extension.

Compliant cores

Power ISA v.2.04

The specification for Power ISA v.2.04[10] was finalized in June 2007. It is based on Power ISA v.2.03 and includes changes primarily to the Book III-S part regarding virtualization, hypervisor functionality, logical partitioning and virtual page handling.

Compliant cores

- All cores that comply with previous versions of the Power ISA

- The PA6T core from P.A. Semi

- Titan from AMCC

Power ISA v.2.05

The specification for Power ISA v.2.05[12] was released in December 2007. It is based on Power ISA v.2.04 and includes changes primarily to Book I and Book III-S, including significant enhancements such as decimal arithmetic (Category: Decimal Floating-Point in Book I) and server hypervisor improvements.

Compliant cores

- All cores that comply with previous versions of the Power ISA

- POWER6

- PowerPC 476

Power ISA v.2.06

The specification for Power ISA v.2.06[11] was released in February 2009, and revised in July 2010.[19] It is based on Power ISA v.2.05 and includes extensions for the POWER7 processor and e500-mc core. One significant new feature is vector-scalar floating-point instructions (VSX).[29] Book III-E also includes significant enhancement for the embedded specification regarding hypervisor and virtualisation on single and multi core implementations.

The spec was revised in November 2010 to the Power ISA v.2.06 revision B spec, enhancing virtualization features.[30]

Compliant cores

Power ISA v.2.07

The specification for Power ISA v.2.07[31] was released in May 2013. It is based on Power ISA v.2.06 and includes major enhancements to logical partition functionality, transactional memory, expanded performance monitoring, new storage control features, additions to the VMX and VSX vector facilities (VSX-2), along with AES[31]: 257 [32] and Galois Counter Mode (GCM), SHA-224, SHA-256,[31]: 258 SHA-384 and SHA-512[31]: 258 (SHA-2) cryptographic extensions and cyclic redundancy check (CRC) algorithms.[33]

The spec was revised in April 2015 to the Power ISA v.2.07 B spec.[34]

Compliant cores

Power ISA v.3.0

The specification for Power ISA v.3.0[28][35] was released in November 2015,[36] It is the first to come out after the founding of the OpenPOWER Foundation and includes enhancements for a broad spectrum of workloads and removes the server and embedded categories while retaining backwards compatibility and adds support for VSX-3 instructions. New functions include 128-bit quad-precision floating point operations, a random number generator, hardware assisted garbage collection and hardware enforced trusted computing.

Compliant cores

Implementations

Processors

- MPC5000, PowerQUICC and QorIQ processors from Freescale

- BlueGene/L and BlueGene/P processors for supercomputers by IBM

- Virtex FPGAs from Xilinx

- V-Dragon CPU from Culturecom

- SeaStar, SeaStar2 and SeaStar+ communications processors in Cray XT3, XT4 and XT5 supercomputers

Systems

- AmigaOne line of computers designed for AmigaOS 4.

- System i, System p, and Power Systems servers, and Blue Gene supercomputers, from IBM

- Power Mac, iBook, eMac, and PowerBook computers, and pre-Intel iMac, Mac Mini, and Xserve computers, from Apple

- Bandai Pippin game system from Bandai (hardware and OS design by Apple)

- BeBox from Be Inc. (discontinued)

- Pegasos/Open Desktop Workstation and Efika PowerPC based computers from Genesi

- TiVo series 1 DVR

- Cell BE and PowerPC based computers from Mercury

- GameCube, Wii and Wii U game consoles from Nintendo

- Xbox 360 from Microsoft

- PlayStation 3 and ZEGO from Sony

- QPACE, a PowerXCell 8i processor based supercomputer for quantum chromodynamics calculations.

- RAD6000 and RAD750, radiation hardened platforms by BAE Systems for use in space

- Routers from Cisco

- Printers, cars, aircraft, medical imaging, telecom equipment, spacecraft, RIPs, set top boxes, etc., from a multitude of companies.

Operating systems

IBM Power architecture supports the following operating systems:[38][39][40]

Other operating systems ported to the Power architecture include:

- AmigaOS 4

- AROS

- eCos open source RTOS

- FreeBSD[41]

- INTEGRITY from Green Hills Software

- Linux from various vendors

- Alpine Linux (supports ppc64le since v3.6)

- Debian (8 and later support ppc64el)

- LynxOS from LynuxWorks

- uC/OS-II from Micrium

- MorphOS

- NetBSD

- OpenBSD

- OS-9 from RadiSys

- OSE from ENEA

- Plan 9 from Bell Labs

- QNX

- RTEMS

- Sony Playstation 3 OS

- VxWorks from Wind River

Historical operating systems include:

- BeOS[42] from Be Inc.

- Linux from various vendors

- CRUX PPC[43] which has been considered eligible to adopt and use Power Source Logo from Power.org

- Yellow Dog Linux from Terra Soft which is specialized for Power Architecture hardware

- MkLinux[44] from Apple, based on Mach micro kernel

- MintPPC from developer Jeroen Diederen

- Debian 8 and earlier includes a PowerPC port[45]

- Mac OS X[44] and Classic Mac OS[42] from Apple

- OpenDarwin

- OpenSolaris

- OS/2 (Workplace OS personality),[42] and i5/OS from IBM

- Solaris[44] from Sun

- Windows NT[44] from Microsoft (until Windows 2000)

See also

- IBM POWER Instruction Set Architecture

- OpenPOWER Foundation

References

- ↑ PowerPC User Instruction Set Architecture Book I, version 2.02

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "PowerPC Book E v.1.0". IBM. 2002-05-07. https://www.nxp.com/docs/en/user-guide/BOOK_EUM.pdf?&fsrch=1. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "PowerPC Architecture Book". IBM. 2003-12-10. Archived from the original on 2007-03-04. https://web.archive.org/web/20070304142505/http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/eserver/articles/archguide.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "PowerPC Architecture Book, Version 2.02". IBM. 2005-02-24. http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/eserver/library/es-archguide-v2.html. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ "AMCC and Power Architecture technology". IBM. http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/pa-nljun04-amcc.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ "Power.org initiative to advance community of electronics innovation" (Press release). Power.org. 2004-12-02. Archived from the original on 2006-05-03. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ "Cell BE Architecture v.1.0". IBM. 2006-03-10. http://www.ibm.com/chips/techlib/techlib.nsf/techdocs/1AEEE1270EA2776387257060006E61BA. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Power ISA v.2.03". Power.org. 2006-09-29. https://www.power.org/technology-introduction/standards-specifications/. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Freescale opened licensing of Power Architecture e200 core family through IPextreme". Power.org. 2007-04-02. http://www.power.org/news/pr/view?item_key=68b01acc02e0cc96b4f0e72103ee2182ea74c08b. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Power ISA Version 2.04". Power.org. 2007-06-12. http://www.power.org/resources/downloads/PowerISA_Public.pdf. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Power.org Debuts Specification Advances and New Services At Power Architecture Developer Conference" (Press release). Power.org. 2007-09-24. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Power ISA Version 2.05". Power.org. 2007-10-23. https://www.power.org/technology-introduction/standards-specifications/. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet & Background: Roadrunner Smashes the Petaflop Barrier". IBM. http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/24405.wss. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ "Freescale QorIQ communications platforms signal a new way forward for embedded multicore technology". Freescale. http://media.freescale.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=196520&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1165849. Retrieved 2008-06-16.

- ↑ "Massive $208 million petascale computer gets green light". http://www.networkworld.com/community/node/32152.

- ↑ http://www.eetimes.com/news/design/rss/showArticle.jhtml?articleID=212300381

- ↑ Feldman, Michael (August 8, 2011). "IBM Bails on Blue Waters Supercomputer". HPCWire. http://www.hpcwire.com/hpcwire/2011-08-08/ibm_bails_on_blue_waters_supercomputer.html. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ↑ "About Blue Waters". https://bluewaters.ncsa.illinois.edu/blue-waters.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Power ISA Version 2.06 Revision B". Power.org. 2010-07-23. https://www.power.org/technology-introduction/standards-specifications/. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ↑ "Mentor Graphics Enables Android on Freescale Products Based on Power Architecture Technology, Reaching New Applications and Audiences". Mentor Graphics. 2009-07-30. http://www.mentor.com/company/news/android-freescale. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

- ↑ "Freescale unveils 64-bit QorIQ platform and extends high-performance product portfolio for multicore processors". Freescale. 2010-10-22. Archived from the original on 2013-01-02. https://archive.is/20130102181726/http://media.freescale.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=196520&p=irol-newsArticle_print&ID=1440425. Retrieved 2010-06-24.

- ↑ "Freescale Drives Embedded Multicore Innovation with New QorIQ Advanced Multiprocessing Series". Freescale. 2011-06-21. http://media.freescale.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=196520&p=irol-newsArticle_print&ID=1576370. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- ↑ "IBM works with Nintendo". nintendoworldreport.com. http://www.nintendoworldreport.com/news/26618. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ IBM Tackles Big Data Challenges with Open Server Innovation Model

- ↑ Tyan Ships First Non-IBM Power8 Server

- ↑ OpenPower Collective Opens For System Business / nextplatform.com, 2015-03

- ↑ Foundation Unveils Slew of OpenPOWER Firsts

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Announcing a New Era of Openness with Power 3.0

- ↑ "Workload acceleration with the IBM POWER vector-scalar architecture". IBM. 2016-03-01. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299472451_Workload_acceleration_with_the_IBM_POWER_vector-scalar_architecture. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- ↑ "Power ISA 2.06 Rev. B enables full hardware virtualization for embedded space". EETimes. 2010-11-03. http://www.eetimes.com/electronics-products/electronic-product-reviews/power-products/4210382/Power-ISA-2-06-Rev-B. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Power ISA Version 2.07". Power.org. 2013-05-15. http://fileadmin.cs.lth.se/cs/education/EDAN25/PowerISA_V2.07_PUBLIC.pdf. Retrieved 2015-05-23.

- ↑ Leonidas Barbosa (2014-09-21). "POWER8 in-core cryptography". IBM. http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/library/se-power8-in-core-cryptography/index.html.

- ↑ Performance Optimization and Tuning Techniques for IBM Power Systems Processors Including IBM POWER8. IBM. August 2015. p. 48. https://books.google.com/books?id=7ph0CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA48&dq=Power+ISA+v.2.07+aes+gcm+sha&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi_nq2hua_RAhUIrFQKHaSuD1gQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=Power%20ISA%20v.2.07%20aes%20gcm%20sha&f=false.

- ↑ "Power ISA Version 2.07 B". Power.org. 2015-04-09. https://openpowerfoundation.org/?resource_lib=ibm-power-isa-version-2-07-b. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ↑ "Power ISA Version 3.0". openpowerfoundation.org. 2016-11-30. https://openpowerfoundation.org/?resource_lib=power-isa-version-3-0. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ↑ "Power ISA version 3.0". IBM. 30 November 2015. https://www.docdroid.net/tWT7hjD/powerisa-v30.pdf.

- ↑ [PATCH, COMMITTED] Add full Power ISA 3.0 / POWER9 binutils support

- ↑ "Power Operating Systems | IBM" (in en-us). https://www.ibm.com/power/operating-systems.

- ↑ "Linux Operating System | IBM" (in en-us). https://www.ibm.com/power/operating-systems/linux.

- ↑ "Supported Linux distributions and virtualization options for POWER8 and POWER9 Linux on Power systems". https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/linuxonibm/liaam/liaamdistros.htm.

- ↑ "POWER8 - FreeBSD Wiki". https://wiki.freebsd.org/POWER8.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 These operating systems have been completely discontinued

- ↑ "CRUX PPC got Power Source logo". CRUXPPC. 2009-07-01. http://cruxppc.org/News#Power_source-logo. Retrieved 2009-07-01.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 These operating systems are discontinued on Power Architecture

- ↑ "Debian -- PowerPC Port". https://www.debian.org/ports/powerpc/.

External links

- Great moments in microprocessor history at IBM

- Power Architecture Primer

- Power.org

- IBM's Power Architecture site

- NXP's Power Architecture site

- STMicroelectronics Power Architecture site

- Applied Micro's embedded processor site

- Mercury's Cell BE site

- Integrated Device Technology Serial RapidIO® Solutions

- Genesi's homepage

- Linux/PPC homepage[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]