Biology:Methionine synthase

Generic protein structure example |

Methionine synthase (MS, MeSe, MTR) is responsible for the regeneration of methionine from homocysteine. In humans it is encoded by the MTR gene (5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase).[1][2] Methionine synthase forms part of the S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) biosynthesis and regeneration cycle,[3] and is the enzyme responsible for linking the cycle to one-carbon metabolism via the folate cycle. There are two primary forms of this enzyme, the Vitamin B12 (cobalamin)-dependent (MetH) and independent (MetE) forms,[4] although minimal core methionine synthases that do not fit cleanly into either category have also been described in some anaerobic bacteria.[5] The two dominant forms of the enzymes appear to be evolutionary independent and rely on considerably different chemical mechanisms.[6] Mammals and other higher eukaryotes express only the cobalamin-dependent form. In contrast, the distribution of the two forms in Archaeplastida (plants and algae) is more complex. Plants exclusively possess the cobalamin-independent form,[7] while algae have either one of the two, depending on species.[8] Many different microorganisms express both the cobalamin-dependent and cobalamin-independent forms.[9]

Mechanism

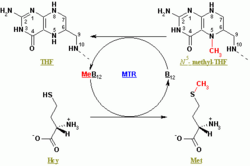

Methionine synthase catalyzes the final step in the regeneration of methionine (Met) from homocysteine (Hcy). Both the cobalamin-dependent and cobalamin-independent forms of the enzyme carry out the same overall chemical reaction, the transfer of a methyl group from 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (N5-MeTHF) to homocysteine, yielding tetrahydrofolate (THF) and methionine.[4] Methionine synthase is the only mammalian enzyme that metabolizes N5-MeTHF to regenerate the active cofactor THF. In the cobalamin-dependent (MetH) form of the enzyme, the reaction proceeds by two steps in a preferred ordered sequential mechanism.[10] The physiological resting state of the enzyme is thought to contain the enzyme-bound(Cob) cofactor in the methylcobalamin form, with the cobalt atom in the formal +3 valence state (Cob(III)-Me). The cobalamin is then demethylated by zinc-activated thiolate homocysteine, generating methionine and reducing the cofactor to a Cob(I) state. When in the Cob(I) form, the enzyme-bound cofactor is now able to abstract a methyl group from activated 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (N5-MeTHF), yielding tetrahydrofolate (THF) and regenerating the methylcoalamin form of the enzyme.[11]

Under physiological conditions, approximately once every 2000 catalytic turnovers the Co(I) may be oxidized into inactive Co(II) in cob-dependent MetH. To account for this effect, the protein contains a self-reactivation mechanism, a reductive methylation process that uses S-adenosylmethionine as a distinct methyl donor. In humans, the enzyme is reduced in this process by methionine synthase reductase (MTRR), which consists of flavodoxin-like and ferrodoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase (FNR)-like domains.[12] In many bacteria, the reduction is carried out by a single domain flavodoxin protein.[13] The reductase protein is responsible for transfer of an electron from a reduced FMN cofactor to the inactive Cob(II), which enables regeneration of the active methylcobalamin enzyme via methyl transfer from S-adenosylmethionine to the reduced Cob(I) intermediate.[14] This process is known as the reactivation cycle, and is thought to be gated from the normal catalytic cycle by large-scale conformational rearrangements within the enzyme.[15] Because the oxidation of Cob(I) inevitably shuts down cob-dependent methionine synthase activity, defects or deficiencies in methionine synthase reductase have been implicated in some of the disease associations for methionine synthase deficiency.[16]

The mechanism of the cobalamin-independent (MetE) form, by contrast, proceeds through a direct methyl transfer from the activated N5-MeTHF to zinc thiolate homocysteine. Although the mechanism is considerably simpler, the direct transfer reaction is much less favorable than the cobalamin-mediated reactions and as a result the turnover rate for MetE is ~100x slower than that of MetH. As it does not contain the cobalamin cofactor, the cobalamin-independent enzyme is not prone to oxidative inactivation [17][4][18][19]

Structure

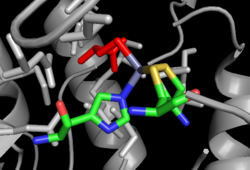

High-resolution structures have been solved by X-ray crystallography for intact MetE both in the absence and presence of substrates[19][18] and for fragments of MetH,[20][21][22][23] although no structural description exists of a fully intact MetH enzyme. The available structures and accompanying bioinformatic analysis indicate minimal similarity in the overall structure, although there are similarities within the substrate-binding sites themselves.[24] Cob-dependent MetH is divided into 4 separate domains. The domains, from N- to C-terminus, are denoted homocysteine binding (Hcy domain), N5-methylTHF binding (MTHF domain) Cobalamin-binding (Cob domain) and the S-adenosymethionine-binding or reactivation domain. The reactivation domain binds SAM and is the site of interaction with flavodoxin or Methionine Synthase Reductase during the reactivation cycle of the enzyme.[13][12][16] The cobalamin-binding domain contains two subdomains, with the cofactor bound to the Rossman-fold B12-binding subdomain, which is in turn capped by the other subdomain, the four-helix bundle cap subdomain.[21] The four-helix bundle serves to protect the cobalamin cofactor from unwanted reactivity, but can significantly change conformations to expose the cofactor allow it access to the other substrates during turnover.[22] Both the Hcy and N5-MeTHF domains adopt a TIM barrel architecture; the Hcy domain contains the zinc-binding site, which in MetH consists of three cysteine residues coordinated to a zinc ion which in turn binds and activates Hcy. The N5-MeTHF binding domain binds and activates N5-MeTHF via a hydrogen bonding network with several asparagine, arginine, and aspartic acid residues. During turnover, the enzyme undergoes significant conformational changes that involve moving the Cob-domain back and forth from the Hcy domain to the N5-MeTHF domain in order for the two methyl transfer reactions to proceed.[20]

The cob-independent MetE consists of two TIM-barrel domains that bind homocysteine and N5-MeTHF individually. The two domains adopt a face-to-face double barrel architecture, which requires a "closing" of the structure upon binding of both substrates to enable the direct methyl transfer.[18] Substrate-binding strategies are similar to MetH, although in the case of MetE the zinc atom is instead coordinated to two cysteines, a histidine and a glutamate,[19] for which an example is shown on the right.

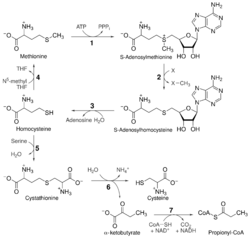

Biochemical function

In humans the enzyme's main purpose is to regenerate Met in the S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) cycle. The SAM cycle in a single turnover consumes Met and ATP and generates Hcy, and can involve any of a number of critical enzymatic reactions that use S-adenosylmethionine as the source of an active methyl group for methylation of nucleic acids, histones, phospholipids and various proteins.[25][26] As such, methionine synthase serves an essential function by allowing the SAM cycle to perpetuate without a constant influx of Met. As a secondary effect, methionine synthase also serves to maintain low levels of Hcy and, because methionine synthase is one of the few enzymes that used N5-MeTHF as a substrate, to indirectly maintain THF levels.[27][28]

In bacteria and plants, methionine synthase serves a dual purpose of both perpetuating the SAM cycle and catalyzing the final synthetic step in the de novo synthesis of Met, which is one of the 20 canonical amino acids.[29][7] While the chemical reaction is exactly the same for both processes, the overall function is distinct from methionine synthase in humans because Met is an essential amino acid that is not synthesized de novo in the body.[30]

Clinical significance

Mutations in the MTR gene have been identified as the underlying cause of methylcobalamin deficiency complementation group G, or methylcobalamin deficiency cblG-type.[1] Deficiency or deregulation of the enzyme due to deficient methionine synthase reductase can directly result in elevated levels of homocysteine (hyperhomocysteinemia), which is associated with blindness, neurological symptoms, and birth defects.[31][32] Methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) or methylene-tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) deficiencies can also result in the condition. Most cases of methionine synthase deficiency are symptomatic within 2 years of birth with many patients rapidly developing severe encephalopathy.[33] One consequence of reduced methionine synthase activity that is measurable by routine clinical blood tests is megaloblastic anemia.

Genetics

Several cblG-associated polymorphisms in the MTR gene have been identified.[34]

- 2756D→G (Asp919Gly)

- 3804C→T (Pro1137Leu)

- Δ2926A-2928T (ΔIle881)

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "MTR 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase (Homo sapiens)". Entrez. 19 May 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=gene&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=4548.

- ↑ "Cloning, mapping and RNA analysis of the human methionine synthase gene". Human Molecular Genetics 5 (12): 1851–1858. December 1996. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.12.1851. PMID 8968735.

- ↑ "Cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase". FASEB Journal 4 (5): 1450–1459. March 1990. doi:10.1096/fasebj.4.5.2407589. PMID 2407589.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Cobalamin-Dependent and Cobalamin-Independent Methionine Synthases: Are There Two Solutions to the Same Chemical Problem?". Helvetica Chimica Acta 86 (12): 3939–3954. 2003. doi:10.1002/hlca.200390329.

- ↑ "Identification and characterization of a bacterial core methionine synthase". Scientific Reports 10 (1): 2100. February 2020. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-58873-z. PMID 32034217. Bibcode: 2020NatSR..10.2100D.

- ↑ "Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (MetE): a face-to-face double barrel that evolved by gene duplication". PLOS Biology 3 (2): e31. February 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030031. PMID 15630480.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The specific features of methionine biosynthesis and metabolism in plants". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95 (13): 7805–7812. June 1998. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.13.7805. PMID 9636232. Bibcode: 1998PNAS...95.7805R.

- ↑ "Insights into the evolution of vitamin B12 auxotrophy from sequenced algal genomes". Molecular Biology and Evolution 28 (10): 2921–2933. October 2011. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr124. PMID 21551270.

- ↑ "Stereochemical analysis of the methyl transfer catalyzed by cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase from Escherichia coli B". Journal of the American Chemical Society 108 (11): 3152–3153. 1986. doi:10.1021/ja00271a081.

- ↑ "Participation of cob(I) alamin in the reaction catalyzed by methionine synthase from Escherichia coli: a steady-state and rapid reaction kinetic analysis". Biochemistry 29 (50): 11101–11109. December 1990. doi:10.1021/bi00502a013. PMID 2271698.

- ↑ Chemistry and biochemistry of B12. Ruma Banerjee. New York: Wiley. 1999. ISBN 0-471-25390-1. OCLC 40397055. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/40397055.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Human methionine synthase reductase is a molecular chaperone for human methionine synthase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (25): 9476–9481. June 2006. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603694103. PMID 16769880. Bibcode: 2006PNAS..103.9476Y.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Interaction of flavodoxin with cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase". Biochemistry 39 (35): 10711–10719. September 2000. doi:10.1021/bi001096c. PMID 10978155.

- ↑ "The mechanism of adenosylmethionine-dependent activation of methionine synthase: a rapid kinetic analysis of intermediates in reductive methylation of Cob(II)alamin enzyme". Biochemistry 37 (36): 12649–12658. September 1998. doi:10.1021/bi9808565. PMID 9730838.

- ↑ "Methionine synthase exists in two distinct conformations that differ in reactivity toward methyltetrahydrofolate, adenosylmethionine, and flavodoxin". Biochemistry 37 (16): 5372–5382. April 1998. doi:10.1021/bi9730893. PMID 9548919.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Protein interactions in the human methionine synthase-methionine synthase reductase complex and implications for the mechanism of enzyme reactivation". Biochemistry 46 (23): 6696–6709. June 2007. doi:10.1021/bi700339v. PMID 17477549.

- ↑ "Mechanism-based design, synthesis and biological studies of N⁵-substituted tetrahydrofolate analogs as inhibitors of cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase and potential anticancer agents". European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 58: 228–236. December 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.09.027. PMID 23124219.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "The cobalamin-independent methionine synthase enzyme captured in a substrate-induced closed conformation". Journal of Molecular Biology 427 (4): 901–909. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2014.12.014. PMID 25545590.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Metal active site elasticity linked to activation of homocysteine in methionine synthases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (9): 3286–3291. March 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709960105. PMID 18296644. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.3286K.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Structures of the N-terminal modules imply large domain motions during catalysis by methionine synthase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101 (11): 3729–3736. March 2004. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308082100. PMID 14752199. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..101.3729E.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "How a protein binds B12: A 3.0 A X-ray structure of B12-binding domains of methionine synthase". Science 266 (5191): 1669–1674. December 1994. doi:10.1126/science.7992050. PMID 7992050.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Domain alternation switches B(12)-dependent methionine synthase to the activation conformation". Nature Structural Biology 9 (1): 53–56. January 2002. doi:10.1038/nsb738. PMID 11731805.

- ↑ "A disulfide-stabilized conformer of methionine synthase reveals an unexpected role for the histidine ligand of the cobalamin cofactor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (11): 4115–4120. March 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800329105. PMID 18332423. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.4115D.

- ↑ "Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase (MetE): a face-to-face double barrel that evolved by gene duplication". PLOS Biology 3 (2): e31. February 2005. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030031. PMID 15630480.

- ↑ "Radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes". Chemical Reviews 114 (8): 4229–4317. April 2014. doi:10.1021/cr4004709. PMID 24476342.

- ↑ "Folate and vitamin B12 metabolism: overview and interaction with riboflavin, vitamin B6, and polymorphisms". Food and Nutrition Bulletin 29 (2 Suppl): S5–S16. June 2008. doi:10.1177/15648265080292S103. PMID 18709878.

- ↑ "Hyperhomocysteinemia due to methionine synthase deficiency, cblG: structure of the MTR gene, genotype diversity, and recognition of a common mutation, P1173L". American Journal of Human Genetics 71 (1): 143–153. July 2002. doi:10.1086/341354. PMID 12068375.

- ↑ "Methionine synthase supports tumour tetrahydrofolate pools". Nature Metabolism 3 (11): 1512–1520. November 2021. doi:10.1038/s42255-021-00465-w. PMID 34799699.

- ↑ "Bacterial methionine biosynthesis". Microbiology 160 (Pt 8): 1571–1584. August 2014. doi:10.1099/mic.0.077826-0. PMID 24939187.

- ↑ "Molecular aspects of methionine biosynthesis". Trends in Plant Science 8 (6): 259–262. June 2003. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00107-9. PMID 12818659.

- ↑ "Cobalamin-dependent methionine synthase". FASEB Journal 4 (5): 1450–1459. March 1990. doi:10.1096/fasebj.4.5.2407589. PMID 2407589.

- ↑ "Causes of hyperhomocysteinemia and its pathological significance". Archives of Pharmacal Research 41 (4): 372–383. April 2018. doi:10.1007/s12272-018-1016-4. PMID 29552692.

- ↑ "Methionine synthase deficiency: a rare cause of adult-onset leukoencephalopathy". Neurology 79 (4): 386–388. July 2012. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318260451b. PMID 22786600.

- ↑ "Defects in human methionine synthase in cblG patients". Human Molecular Genetics 5 (12): 1859–1865. December 1996. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.12.1859. PMID 8968736.

Further reading

- "Structure-based perspectives on B12-dependent enzymes". Annual Review of Biochemistry 66: 269–313. 1997. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.269. PMID 9242908.

- "Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase: biochemistry and molecular biology". European Journal of Pediatrics 157 (Suppl 2): S54–S59. April 1998. doi:10.1007/PL00014305. PMID 9587027. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1120&context=lawfacpub.

- "Methionine auxotrophy in inborn errors of cobalamin metabolism". Clinical and Investigative Medicine 15 (4): 395–400. August 1992. PMID 1516297.

- "The impact of iron deficiency on the flux of folates within the mammary gland". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research 62 (2): 173–180. 1992. PMID 1517041.

- "Aging, chronic administration of ethanol, and acute exposure to nitrous oxide: effects on vitamin B12 and folate status in rats". Mechanisms of Ageing and Development 62 (3): 229–243. March 1992. doi:10.1016/0047-6374(92)90109-Q. PMID 1583909.

- "Lysosomal cobalamin accumulation in fibroblasts from a patient with an inborn error of cobalamin metabolism (cblF complementation group): visualization by electron microscope radioautography". Experimental Cell Research 195 (2): 295–302. August 1991. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(91)90376-6. PMID 2070814.

- "Cloning, mapping and RNA analysis of the human methionine synthase gene". Human Molecular Genetics 5 (12): 1851–1858. December 1996. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.12.1851. PMID 8968735.

- "Defects in human methionine synthase in cblG patients". Human Molecular Genetics 5 (12): 1859–1865. December 1996. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.12.1859. PMID 8968736.

- "Human methionine synthase: cDNA cloning and identification of mutations in patients of the cblG complementation group of folate/cobalamin disorders". Human Molecular Genetics 5 (12): 1867–1874. December 1996. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.12.1867. PMID 8968737.

- "Human methionine synthase. cDNA cloning, gene localization, and expression". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 272 (6): 3628–3634. February 1997. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.6.3628. PMID 9013615.

- "Functionally null mutations in patients with the cblG-variant form of methionine synthase deficiency". American Journal of Human Genetics 63 (2): 409–414. August 1998. doi:10.1086/301976. PMID 9683607.

- "Methionine synthase A2756G and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase A1298C polymorphisms are not risk factors for idiopathic venous thromboembolism". The Hematology Journal 2 (1): 38–41. 2002. doi:10.1038/sj.thj.6200078. PMID 11920232.

- "Hyperhomocysteinemia due to methionine synthase deficiency, cblG: structure of the MTR gene, genotype diversity, and recognition of a common mutation, P1173L". American Journal of Human Genetics 71 (1): 143–153. July 2002. doi:10.1086/341354. PMID 12068375.

- "Study of MTHFR and MS polymorphisms as risk factors for NTD in the Italian population". Journal of Human Genetics 47 (6): 319–324. 2002. doi:10.1007/s100380200043. PMID 12111380.

- "Maternal genetic effects, exerted by genes involved in homocysteine remethylation, influence the risk of spina bifida". American Journal of Human Genetics 71 (5): 1222–1226. November 2002. doi:10.1086/344209. PMID 12375236.

- "Homocysteine remethylation enzyme polymorphisms and increased risks for neural tube defects". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 78 (3): 216–221. March 2003. doi:10.1016/S1096-7192(03)00008-8. PMID 12649067.

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Disorders of Intracellular Cobalamin Metabolism

- ENZYME: EC 2.1.1.13

- 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate-Homocysteine+S-Methyltransferase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

|