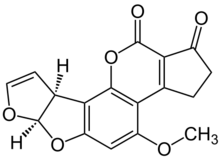

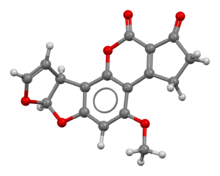

Chemistry:Aflatoxin B1

Chemical structure of (–)-aflatoxin B1

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

(6aR,9aS)-4-Methoxy-2,3,6a,9a-tetrahydrocyclopenta[c]furo[3′,2′:4,5]furo[2,3-h][1]benzopyran-1,11-dione | |

| Other names

NSC 529592

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C17H12O6 | |

| Molar mass | 312.277 g·mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Carcinogen – Mutagen – Acute toxicity / Poison[3] |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

| H300, H310, H330, H340, H350 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P262, P264, P270, P271, P280, P281, P284, P301+330+331, P310, P302+350, P304+340, P311, P308+313, P320, P321, P322, P330, P361, P363, P403+233, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Aflatoxin B1 is an aflatoxin produced by Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. It is a very potent carcinogen with a TD50 3.2 μg/kg/day in rats.[4] This carcinogenic potency varies across species with some, such as rats and monkeys, seemingly much more susceptible than others.[5][6] Aflatoxin B1 is a common contaminant in a variety of foods including peanuts, cottonseed meal, corn, and other grains;[7] as well as animal feeds.[8] Aflatoxin B1 is considered the most toxic aflatoxin and it is highly implicated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in humans.[citation needed] In animals, aflatoxin B1 has also been shown to be mutagenic,[9] teratogenic,[10] and to cause immunosuppression.[11] Several sampling and analytical methods including thin-layer chromatography (TLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), mass spectrometry, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), among others, have been used to test for aflatoxin B1 contamination in foods.[12] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), a division of the United Nations , the worldwide maximum tolerated levels of aflatoxin B1 was reported to be in the range of 1–20 μg/kg (or .001 ppm - 1 part-per-billion) in food, and 5–50 μg/kg (.005 ppm) in dietary cattle feed in 2003.[13]

Sources of exposure

Aflatoxin B1 is mostly found in contaminated food and humans are exposed to aflatoxin B1 almost entirely through their diet.[14] Occupational exposure to aflatoxin B1 has also been reported in swine[15] and poultry production.[16] While aflatoxin B1 contamination is common in many staple foods, its production is maximized in foods stored in hot, humid climates.[17] Exposure is therefore most common in Southeast Asia, South America, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[17]

Pathology

Aflatoxin B1 can permeate through the skin. Dermal exposure to this aflatoxin in particular environmental conditions can lead to major health risks.[18] The liver is the most susceptible organ to aflatoxin B1 toxicity. In animal studies, pathological lesions associated with aflatoxin B1 intoxication include reduction in weight of liver,[19] vacuolation of hepatocytes,[20] and hepatic carcinoma.[21] Other liver lesions include enlargement of hepatic cells, fatty infiltration, necrosis, hemorrhage, fibrosis, regeneration of nodules, and bile duct proliferation/hyperplasia.[22]

Aspergillus flavus

Aspergillus flavus is a fungus of the family Trichocomaceae with a worldwide distribution. The mold lives in soil, surviving off dead plant and animal matter, but spreads through the air via airborne conidia.[23] This fungus grows in long branched hyphae and is capable of surviving on numerous food sources including corn and peanuts.[24] The fungus and its products are pathogenic to a number of species, including humans.[23] While toxicity of its products, aflatoxins, are explored throughout this article, Aspergillus flavus itself also exerts pathogenic effects through aspergillosis, or infection with the mold. This infection largely occurs in the lungs of immune compromised patients but infection may also occur in the skin or other organs.[25] Unlike many mold species, Aspergillus flavus prefers hot and dry conditions. Its optimal growth at 37 °C (99 °F) contributes to its pathogenicity in humans.[23]

Biosynthetic pathway

Aflatoxin B1 is derived from both a dedicated fatty acid synthase (FAS) and a polyketide synthase (PKS), together known as norsolorinic acid synthase. The biosynthesis begins with the synthesis of hexanoate by the FAS, which then becomes the starter unit for the iterative type I PKS.[26][27][28] The PKS adds seven malonyl-CoA extenders to the hexanoate to form the C20 polyketide compound. The PKS folds the polyketide in a particular way to induce cyclization to form the anthraquinone norsolorinic acid. A reductase then catalyzes the reduction of the ketone on the norsolorinic acid side-chain to yield averantin.[26][27][28] Averantin is converted to averufin via a two different enzymes, a hydroxylase and an alcohol dehydrogenase. This will oxygenate and cyclize averantin's side chain to form the ketal in averufin.

From this point on the biosynthetic pathway of aflatoxin B1 becomes much more complicated, with several major skeletal changes. Most of the enzymes have not been characterized and there may be several more intermediates that are still unknown.[26] However, what is known is that averufin is oxidized by a P450-oxidase, AvfA, in a Baeyer-Villiger oxidation. This opens the ether rings and upon rearrangement versiconal acetate is formed. Now an esterase, EstA, catalyzes the hydrolysis of the acetyl, forming the primary alcohol in versiconal.[26][28] The acetal in versicolorin A is formed from the cyclization of the side-chain in versiconal, which is catalyzed by VERB synthase, and then VerB, a desaturase, reduces versicolorin B to form the dihydrobisfuran.[26][28]

There are two more enzymes that catalyze the conversion of versicolorin A to demethylsterigmatocystin: AflN, an oxidase and AflM, a reductase. These enzymes use both molecular oxygen and two NADPH's to dehydrate one of the hydroxyl groups on the anthraquinone and open the quinine with the molecular oxygen.[26][28] Upon forming the aldehyde in the ring opening step, it is oxidized to form the carboxylic acid and subsequently a decarboxylation event occurs to close the ring, forming the six-member ether ring system seen in demethylsterigmatocystin. The next two steps in the biosynthetic pathway is the methylation by S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) of the two hydroxyl groups on the xanthone part of demethysterigmatocystin by two different methyltransferases, OmtB and OmtA.[26][28] This yields O-methylsterigmatocystin. In the final steps there is an oxidative cleavage of the aromatic ring and loss of one carbon in O-methylsterigmatocystin, which is catalyzed by OrdA, an oxidoreductase.[26][28] Then a final recyclization occurs to form aflatoxin B1.

Mechanism of carcinogenicity

Aflatoxin B1 is a potent genotoxic hepatocarcinogen with its exposure strongly linked to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, liver tumors, especially given co-infection with hepatitis B virus.[17] These effects seem to be largely mediated by mutations at guanine in codon 249 of the p53 gene, a tumor suppressing gene,[29] and at several guanine residues in the 12th and 13th codons of the ras gene, a gene whose product controls cellular proliferation signals.[30][31] Aflatoxin B1 must first be metabolized into its reactive electrophilic form, aflatoxin B1-8,9-exo-epoxide by cytochrome p450.[17] This active form then intercalates between DNA base residues and forms adducts with guanine residues, most commonly aflatoxin B1-N7-Gua. These adducts may then rearrange or become removed from the backbone all-together, forming an apurinic site. These adducts and alterations represent lesions which, upon DNA replication cause the insertion of a mis-matched base in the opposing strand. Up to 44% of hepatocellular carcinomas in regions with high aflatoxin exposure bear a GC → TA transversion at codon 249 of p53, a characteristic mutation seen with this toxin.[31]

Prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma in individuals exposed to aflatoxin, increases with co-infection of hepatitis B virus. One study estimated that while individuals with urinary aflatoxin bio-markers were at a threefold greater risk than the normal population for hepatocellular carcinoma; those infected with hepatitis B virus were at a fourfold risk; and those with the aflatoxin bio-markers and infected with hepatitis B virus were at a 60 times greater risk for hepatocellular carcinoma than the normal population.[32][31]

Toxicity

Several aflatoxin B1 toxicity studies have been conducted on various animal species.[33]

- Acute toxicity

- The oral LD50 range of aflatoxin B1 is estimated to be 0.3–17.9 mg/kg body weight for most animal species.[34] For instance, the oral LD50 of aflatoxin B1 is estimated to be 17.9 mg/kg body weight in female rats and 7.2 mg/kg body weight in male rats. Still in male rats, the intraperitoneal LD50 of aflatoxin B1 is estimated to be 6.0 mg/kg body weight.[35] Symptoms include anorexia, malaise, and low-grade fever.[36]

- Subacute toxicity

- Subacute toxicity studies of aflatoxin B1 in animals showed moderate to severe liver damage. In monkeys for instance, subacute toxicity studies showed portal inflammation and fatty change.[37]

- Chronic toxicity

- Chronic toxicity studies of aflatoxin B1 in chickens showed decreased hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450 concentration, reduction in feed consumption and decreased weight gain.[38]

- Subchronic toxicity

- Subchronic toxicity studies of aflatoxin B1 in fish showed fish to present with preneoplastic lesions, concurrently with changes in gill, pancreas, intestine and spleen.[39]

- Genotoxicity

- Treatment of human liver cells with aflatoxin B1 at doses that ranged from 3–5 μmol/L resulted in the formation of aflatoxin B1-DNA adducts, 8-hydroxyguanine lesions and DNA damage.[40]

- Carcinogenicity

- The carcinogenicity of aflatoxin B1, which is characterized by the development of liver cell carcinoma, has been reported in rat studies.[41]

- Embryotoxicity

- Embryonic death and impaired embryonic development of the bursa of Fabricius in chickens by aflatoxin B1 has been reported.[42]

- Teratogenicity

- The teratogenic effects of aflatoxin B1 in rabbits have been reported to include reduced fetal weights, wrist drop, enlarged eye socket, agenesis of caudal vertebrae, micropthalmia, cardiac defects, and lenticular degeneration, among others.[43]

- Immunotoxicity

- Studies in fish showed aflatoxin B1 to have significant immunosuppressive effects including reduced serum total globulin and reduced bactericidal activities.[44]

Risk management and regulations

Aflatoxin B1 exposure is best managed by measures aimed at preventing contamination of crops in the field, post-harvest handling, and storage, or via measures aimed at detecting and decontaminating contaminated commodities or materials used in animal feed. For instance, biological decontamination involving the use of a single bacterial species, Flavobacterium aurantiacum has been used to remove aflatoxin B1 from peanuts and corn.[45]

Several countries around the world have rules and regulations governing aflatoxin B1 in foods and these include the maximum permitted, or recommended levels of aflatoxin B1 for certain foods.[46]

- United States (US)

- US food safety regulations have set a maximum permitted level of 20 μg/kg for aflatoxin B1, in combination with the other aflatoxins (B2, G1 and G2) in all foods, with the exception of milk which has a maximum permitted level of 0.5 μg/kg. Higher levels of 100–300 μg/kg are tolerable for some animal feeds.[47][48]

- European Union (EU)

- The EU has set maximum permitted levels for aflatoxin B1 in nuts, dried fruits, cereals and spices to range from 2–12 μg/kg, while the maximum permitted level for aflatoxin B1 in infant foods is set at 0.1 μg/kg.[45] The maximum permitted levels for aflatoxin B1 in animal feeds set by the EU range from 5–50 μg/kg and these levels are much lower than those set in the US.[49]

- Joint United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)/World Health Organization (WHO) Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA)

- The FAO/WHO JECFA has set the maximum permitted levels of aflatoxin B1 in combination with the other aflatoxins (B2, G1 and G2) to be 15 μg/kg in raw peanuts and 10 μg/kg in processeds peanut; while the tolerance level of aflatoxin B1 alone is 5 μg/kg for dairy cattle feed.[50][51]

Notable exposures

The discovery of aflatoxin B1 came on the heels of the widespread death of turkeys in England in the summer of 1960 to some unknown disease, at the time labeled "Disease X". Over the course of 500 outbreaks, the disease claimed over 100,000 turkeys which appeared to be healthy. The widespread death was later found to be caused by Aspergillus flavus contamination of peanut meal.[52][53]

Twelve patients died of acute aflatoxin poisoning in several hospitals in the Machakos district of Kenya in 1981 following the consumption of contaminated maize. All patients also suffered from hepatitis.[54]

Following outbreaks of aflatoxin contamination in maize reaching 4,400 ppb in the spring of 2004, 125 individuals in Kenya died of acute hepatic failure while some 317 cases in total were reported. To date this was the largest known outbreak of aflatoxicosis in terms of fatalities documented.[36]

References

- ↑ "AFLATC : Aflatoxin B1 chloroform solvate". Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/Search?Ccdcid=AFLATC&DatabaseToSearch=Published.

- ↑ van Soest, T. C.; Peerdeman, A. F. (1970). "The crystal structures of aflatoxin B1. I. The structure of the chloroform solvate of aflatoxin B1 and the absolute configuration of aflatoxin B1". Acta Crystallogr. B 26 (12): 1940–1947. doi:10.1107/S0567740870005228.

- ↑ PubChem

- ↑ "Summary Table by Chemical of Carcinogenicity Results in CPDB on 1547 Chemicals". https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cpdb/pdfs/ChemicalTable.pdf.

- ↑ McLean, M (February 1995). "Cellular interactions and metabolism of aflatoxin: an update". Pharmacology & Therapeutics 65 (2): 163–192. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(94)00054-7. PMID 7540767.

- ↑ Aflatoxin B1 (CAS 1162-65-8) The Carcinogenic Potency Project.

- ↑ Galvano F., Ritieni A., Piva G., Pietri A. Mycotoxins in the human food chain. In: Diaz D.E., editor. The Mycotoxin Blue Book. Nottingham University Press; Nottingham, UK: 2005. pp. 187–224.

- ↑ Azab Rania M.; Tawakkol Wael M.; Abdel-Rahman M. Hamad; Abou-Elmagd Mohamed K.; El-Agrab Hassan M.; Refai Mohamed K. (2005). "Detection and estimation of aflatoxin B1 in feeds and its biodegradation by bacteria and fungi". Egyptian Journal of Natural Toxins 2: 39–56.

- ↑ Chen, Tao; Heflich, Robert H; Moore, Martha M; Mei, Nan (2009). "Differential mutagenicity of aflatoxin B1in the liver of neonatal and adult mice". Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis 51 (2): 156–63. doi:10.1002/em.20518. PMID 19642212.

- ↑ Geissler, Francis; Faustman, Elaine M (1988). "Developmental toxicity of aflatoxin B1 in the rodent embryo in vitro: Contribution of exogenous biotransformation systems to toxicity". Teratology 37 (2): 101–11. doi:10.1002/tera.1420370203. PMID 3127910.

- ↑ "Immunotoxicity of aflatoxin B1: Impairment of the cell-mediated response to vaccine antigen and modulation of cytokine expression". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 231 (2): 142–9. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.04.004. PMID 18501398.

- ↑ Wacoo Alex P.; Wendiro Deborah; Vuzi Peter C.; Hawumba Joseph F. (2014). "Methods for Detection of Aflatoxins in Agricultural Food Crops". Journal of Applied Chemistry 2014: 1–15. doi:10.1155/2014/706291.

- ↑ "Worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 2003". http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5499e/y5499e07.htm#bm07.4.1.

- ↑ Coulombe R. A. (1993). "Biological action of mycotoxins". J Dairy Sci 76 (3): 880–891. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(93)77414-7. PMID 8463495.

- ↑ Viegas, Susana; Veiga, Luísa; Figueredo, Paula; Almeida, Ana; Carolino, Elisabete; Sabino, Raquel; Veríssimo, Cristina; Viegas, Carla (2013). "Occupational Exposure to Aflatoxin B1in Swine Production and Possible Contamination Sources". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 76 (15): 944–951. doi:10.1080/15287394.2013.826569. PMID 24156697.

- ↑ Viegas, Susana; Veiga, Luisa; Malta-Vacas, Joana; Sabino, Raquel; Figueredo, Paula; Almeida, Ana; Viegas, Carla; Carolino, Elisabete (2012). "Occupational Exposure to Aflatoxin (AFB1) in Poultry Production". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A 75 (22–23): 1330–1340. doi:10.1080/15287394.2012.721164. PMID 23095151.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Kew, MC (September 2013). "Aflatoxins as a cause of hepatocellular carcinoma". Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases 22 (3): 305–310. PMID 24078988.

- ↑ Boonen, Jente; Malysheva, Svetlana V.; Taevernier, Lien; Diana Di Mavungu, José; De Saeger, Sarah; De Spiegeleer, Bart (2012). "Human skin penetration of selected model mycotoxins". Toxicology 301 (1–3): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.012. PMID 22749975.

- ↑ Fernández A, Ramos JJ, Sanz M, Saez T, Fernández de Luco D (1996). Alterations in the performance, haematology and clinical biochemistry of growing lambs fed with aflatoxin in the diet. J Appl Toxicol. 16(1): 85-91.

- ↑ Espada Y, Domingo M, Gomez J, Calvo MA (1992). Pathological lesions following an experimental intoxication with aflatoxin B1 in broiler chickens. Res Vet Sci. 53(3): 275-9.

- ↑ "Hepatic and extrahepatic bioactivation and GSH conjugation of aflatoxin B1 in sheep". Carcinogenesis 15 (5): 947–55. 1994. doi:10.1093/carcin/15.5.947. PMID 8200100.

- ↑ Patterson D.S.P. Aflatoxin and related compounds: Introduction. In: Wyllie T.D., Morehouse L.G., editors. Mycotoxic Fungi, Mycotoxins, Mycotoxicoses, an Encyclopaedic Handbook. 1st. Vol. 1. Marcel Dekker Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1977. pp. 131–135.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Hedayati, M. T.; Pasqualotto, A. C.; Warn, P. A.; Bowyer, P.; Denning, D. W. (2007-01-01). "Aspergillus flavus: human pathogen, allergen and mycotoxin producer". Microbiology 153 (6): 1677–1692. doi:10.1099/mic.0.2007/007641-0. PMID 17526826.

- ↑ "Aspergillus flavus :: Center for Integrated Fungal Research". http://www.cifr.ncsu.edu/aflavus/.

- ↑ "Definition of Aspergillosis | Aspergillosis | Types of Fungal Diseases | Fungal Diseases | CDC" (in en-us). https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/aspergillosis/definition.html.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 26.7 Dewick, P.M. (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). Wiley. pp. 122–4. ISBN 978-0470742792. https://books.google.com/books?id=SeKMT1u3dugC&pg=SA3-PA96.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway: elucidation by using blocked mutants of Aspergillus parasiticus". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 178 (1): 285–92. January 1977. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(77)90193-x. PMID 836036.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 "Clustered pathway genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 (3): 1253–62. March 2004. doi:10.1128/AEM.70.3.1253-1262.2004. PMID 15006741. Bibcode: 2004ApEnM..70.1253Y.

- ↑ (us), National Center for Biotechnology Information (1998-01-01). The p53 tumor suppressor protein. National Center for Biotechnology Information (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22268/.

- ↑ Fernández-Medarde, Alberto; Santos, Eugenio (2017-05-08). "Ras in Cancer and Developmental Diseases". Genes & Cancer 2 (3): 344–358. doi:10.1177/1947601911411084. ISSN 1947-6019. PMID 21779504.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Semela, Maryann (2001). "The chemistry and biology of aflatoxin B1: from mutational spectrometry to carcinogenesis". Carcinogenesis 22 (4): 535–545. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.4.535. PMID 11285186. https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/carcin/22/4/10.1093_carcin_22.4.535/1/220535.pdf?Expires=1494259529&Signature=e7izXWvJIoeZRUXuHsOtiSydzP7wsNwf11qMZOjvuYq2lZlNcGiZIUPCpM2WbhYf0TsnLttTSGerCk5qHKIy9VtR0JNT2Z62quROcwgm6mX9TMuUqGHF7CGSvI1Qhg-AtPTGeO2luYVj2NznWhgrHKCgm1rWVSY6p8OsKryOg~OJ27Ige2xDi4sKtLN1yGKz87Mm9y4WdIH7-KieSRQhEkk~UxOMmSVfUEgh5QtWQMKUOC7r~xR06Dxl5mn2gtxNNh0L4cGAnCThiPLsCv5Tq94ocWIVnJA5jjcNU1OTjL8fI5a9Gavw8Vz6fbp6g2jAyHUYQ6zwleUItgA1OllphQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIUCZBIA4LVPAVW3Q.

- ↑ Ross, R. K.; Yuan, J. M.; Yu, M. C.; Wogan, G. N.; Qian, G. S.; Tu, J. T.; Groopman, J. D.; Gao, Y. T. et al. (1992-04-18). "Urinary aflatoxin biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma". Lancet 339 (8799): 943–946. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)91528-g. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 1348796.

- ↑ Wogan Gerald N (1966). "Chemical Nature and Biological Effects of the Aflatoxins". Bacteriol. Rev. 30 (2): 460–470. doi:10.1128/BR.30.2.460-470.1966. PMID 5327461.

- ↑ Agag B.I. (2004). "Mycotoxins in foods and feeds 1-Aflatoxins". Ass Univ. Bull. Environ. Res. 7 (1): 173–205.

- ↑ Butler W. H. (1964). "Acute Toxicity of Aflatoxin B1 in Rats". Br J Cancer 18 (4): 756–762. doi:10.1038/bjc.1964.87. PMID 14264941.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Azziz-Baumgartner, Eduardo; Lindblade, Kimberly; Gieseker, Karen; Rogers, Helen Schurz; Kieszak, Stephanie; Njapau, Henry; Schleicher, Rosemary; McCoy, Leslie F. et al. (2005-01-01). "Case-Control Study of an Acute Aflatoxicosis Outbreak, Kenya, 2004". Environmental Health Perspectives 113 (12): 1779–1783. doi:10.1289/ehp.8384. PMID 16330363.

- ↑ Tulpule P. G.; Madhavan T. V.; Gopalan C. (1964). "Effect of feeding aflatoxin in young monkeys". Lancet 1 (7340): 962–3. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(64)91748-9. PMID 14121357.

- ↑ Dalvi, R. R; McGowan, C (1984). "Experimental Induction of Chronic Aflatoxicosis in Chickens by Purified Aflatoxin B1 and Its Reversal by Activated Charcoal, Phenobarbital, and Reduced Glutathione". Poultry Science 63 (3): 485–91. doi:10.3382/ps.0630485. PMID 6425817.

- ↑ Sahoo PK, Mukherjee SC, Nayak SK, Dey S (2001). Acute and subchronic toxicity of aflatoxin B1 to rohu, Labeo rohita (Hamilton). Indian J Exp Biol. 39(5): 453-8.

- ↑ Gursoy-Yuzugullu, Ozge; Yuzugullu, Haluk; Yilmaz, Mustafa; Ozturk, Mehmet (2011). "Aflatoxin genotoxicity is associated with a defective DNA damage response bypassing p53 activation". Liver International 31 (4): 561–71. doi:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02474.x. PMID 21382167.

- ↑ Newberne Paul M., Wogan Gerald N. (1968). "Sequential Morphologic Changes in Aflatoxin B1 Carcinogenesis in the Rat". Cancer Res 28 (4): 770–781. PMID 4296938.

- ↑ Sur, E; Celik, İ (2003). "Effects of aflatoxin B1on the development of the bursa of Fabricius and blood lymphocyte acid phosphatase of the chicken". British Poultry Science 44 (4): 558–66. doi:10.1080/00071660310001618352. PMID 14584846.

- ↑ Wangikar, P.B; Dwivedi, P; Sinha, N; Sharma, A.K; Telang, A.G (2005). "Effects of aflatoxin B1 on embryo fetal development in rabbits". Food and Chemical Toxicology 43 (4): 607–15. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2005.01.004. PMID 15721209.

- ↑ Sahoo PK, Mukherjee SC (2001). Immunosuppressive effects of aflatoxin B1 in Indian major carp (Labeo rohita). Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 24(3):143-9.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Aflatoxins". http://www.foodsafetywatch.org/factsheets/aflatoxins/.

- ↑ Rustom, Ismail Y.S (1997). "Aflatoxin in food and feed: Occurrence, legislation and inactivation by physical methods". Food Chemistry 59: 57–67. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(96)00096-9.

- ↑ Park, D. L. & Njapau, H. (1989). Contamination issues and padding. J. Am. Oil Chem. Sot. 66: 1402-1405.

- ↑ Park, D. L. & Liang, B. (1993). Perspectives on aflatoxin control for human food and animal feed.Trends Food Sci. Technol. 4: 334-342.

- ↑ EEC (1991). EEC Council Directive 91/126/EEC. Amending the annexes to Council Directive 74/63/EEC on undesirable substances and products in animal nutrition. Off. J. Eur. Commun., No. L 60.

- ↑ FAO/WHO (1990). FAO/WHO Standards Programme. Codex Alimentarius Commission, Alinorm 91/29.

- ↑ FAO/WHO (1992). FAO/WHO Standards Programme. Codex Alimentarius Commission, Alinorm 93/12.

- ↑ Wannop, C. C. (1961-01-01). "The Histopathology of Turkey "X" Disease in Great Britain". Avian Diseases 5 (4): 371–381. doi:10.2307/1587768.

- ↑ Richard, John L. (2008-01-01). "Discovery of Aflatoxins and Significant Historical Features". Toxin Reviews 27 (3–4): 171–201. doi:10.1080/15569540802462040. ISSN 1556-9543.

- ↑ Ngindu Augustine (1982). "Outbreak of Acute Hepatitis Caused by Aflatoxin Poisoning in Kenya" (in en). The Lancet 319 (8285): 1346–1348. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92411-4. PMID 6123648.

External links

|