Biology:Hemolithin

| Hemolithin | ||

|---|---|---|

| (iron and lithium-containing protein, possibly extraterrestrial[1][2][3][4]) | ||

| ||

| Function | unknown, although possibly able to split water to hydroxyl and hydrogen moieties[1] | |

|

| ||

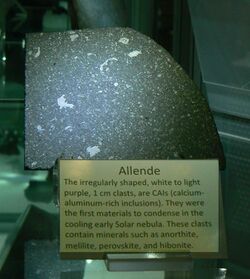

Hemolithin is an iron and lithium-containing protein of extraterrestrial origin according to an unpublished preprint.[1] The protein was purportedly found inside two CV3 meteorites, Allende and Acfer-086,[5][2][3] by a team of scientists led by Harvard University biochemist Julie McGeoch.[1][3] The report of the discovery was met with some skepticism and suggestions that the researchers had extrapolated too far from incomplete data.[7][8] However, X-ray analysis of the crystalized polymer was performed by the same researchers at the APS, Argonne National Laboratory, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357, and published in June 2021.[9]

Sources

The detected hemolithin protein was reported to have been found inside two CV3 meteorites Allende and Acfer 086.[5] Acfer-086, where the complete molecule was detected rather than fragments (Allende), was discovered in Agemour, Algeria in 1990.[3][6]

Structure

According to the researchers' mass spectrometry, hemolithin is largely composed of glycine and hydroxyglycine amino acids.[8] The researchers noted that the protein was related to “very high extraterrestrial" ratios of Deuterium/Hydrogen (D/H);[3] such high D/H ratios are not found anywhere on Earth, but are "consistent with long-period comets"[4] and suggest, as reported, "that the protein was formed in the proto-solar disc or perhaps even earlier, in interstellar molecular clouds that existed long before the Sun’s birth".[3]

A natural development of hemolithin may have started with glycine forming first, and then later linking with other glycine molecules into polymer chains, and later still, combining with iron and oxygen atoms. The iron and oxygen atoms reside at the end of the newly found molecule. The researchers speculate that the iron oxide grouping formed at the end of the molecule may be able to absorb photons, thereby enabling the molecule to split water (H2O) into hydrogen and oxygen and, as a result, produce a source of energy that might be useful to the development of life.[3]

Exobiologist and chemist Jeffrey Bada expressed concerns about the possible protein discovery commenting, "The main problem is the occurrence of hydroxyglycine, which, to my knowledge, has never before been reported in meteorites or in prebiotic experiments. Nor is it found in any proteins. ... Thus, this amino acid is a strange one to find in a meteorite, and I am highly suspicious of the results."[8] Likewise, Lee Cronin of the University of Glasgow stated, "The structure makes no sense."[7]

In June 2021, related X-ray structural studies on purified polymers from meteorites were reported.[9] According to the researchers, the polymer of chains of glycine (rods of glycine) with silicon, iron, oxygen and lithium formed at least 4.5 billion years ago in a molecular cloud prior to the formation of our solar system. It was extracted from micron particles of Acfer-086, a CV3 meteorite. Such meteorites form when matter in molecular clouds accretes in the process of forming a solar system and some fall to Earth, allowing analysis of early space molecules. Further, the researchers noted that this polymer type could be responsible for the accretion of all material in the Universe which would mean it first formed 12.5 billion years ago. The polymer forms a very low-density space filling lattice which at 32 mg/cm3 is 30 times less dense than water. Such a structure as it swept through the near vacuum of space would collect the largest amount of glycine molecules to produce additional rod polymers that could be added to the structure. Carried to completion, such a process would sweep up most of the material in a protoplanetary disc to create planetary bodies, small and large – the “accretion” process not well-explained prior to this work. It's noted that the very existence of our planet may owe a lot to the behavior of a small protein-like molecule in the nascent solar system. Earlier calculations (in 2014) show that a similar process will be possible at the formation of other solar systems throughout the Universe.[10]

History

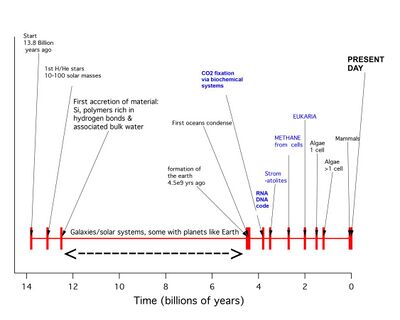

Hemolithin is the name given to a protein molecule isolated from two CV3 meteorites, Allende and Acfer-086. Its deuterium to hydrogen ratio is 26 times terrestrial which is consistent with it having formed in an interstellar molecular cloud, or later in the protoplanetary disk at the start of our solar system 4.567 billion years ago. The elements hydrogen, lithium, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and iron that it is composed of, were all available for the first time 13 billion years ago after the first generation of massive stars ended in nucleosynthetic events. The horizontal arrow in the time line graph below shows, on the scale of the start of the Universe to the present, when Hemolithin could have formed and reformed.

The research leading to the discovery of Hemolithin started in 2007 when another protein, one of the first to form on Earth, was observed to entrap water.[11] That property being useful to chemistry before biochemistry on earth developed, theoretical enthalpy calculations on the condensation of amino acids were performed in gas phase space asking: “whether amino acids could polymerize to protein in space?” - they could, and their water of condensation aided their polymerization.[10] This led to several manuscripts of isotope and mass information on Hemolithin.[1][12][13][14]

See also

- Abiogenesis

- Astrobiology

- Earliest known life forms

- Evolutionary history of life

- Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth

- List of interstellar and circumstellar molecules

- Panspermia

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 McGeoch, Malcolm. W.; Dikler, Sergei; McGeoch, Julie E. M. (22 February 2020). "Hemolithin: a Meteoritic Protein containing Iron and Lithium". arXiv:2002.11688 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McGeoch, Malcolm. W.; Dikler, Sergei; McGeoch, Julie E. M. (21 February 2021). "Meteoritic Proteins with Glycine, Iron and Lithium". arXiv:2102.10700 [physics.chem-ph].

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Ferreira, Becky (28 February 2020). "A Key Ingredient for Life Has Been Found on an 'Extraterrestrial Source,' Scientists Report in this unpublished report.". Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/z3bw38/a-key-ingredient-for-life-has-been-found-on-an-extraterrestrial-source-scientists-report.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Starr, Michelle (2 March 2020). "Scientists Claim to Have Found The First Known Extraterrestrial Protein in a Meteorite". ScienceAlert.com. https://www.sciencealert.com/scientists-claim-to-have-found-the-first-known-extraterrestrial-protein-in-a-meteorite.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Staff (3 March 2020). "Acfer 086". The Meteoritical Society. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meteor/metbull.php?code=95.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wlotza, Frank (1 September 1991). "Meteoritical Bulletin, No. 71". Meteoritical Bulletin 26 (71): 255–262. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1991.tb01047.x. Bibcode: 1991Metic..26..255W. http://adsbit.harvard.edu/cgi-bin/nph-iarticle_query?1991Metic..26..255W. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Crane, Leah (3 March 2020). "Have we really found an alien protein inside a meteorite?". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2235981-have-we-really-found-an-alien-protein-inside-a-meteorite/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Wall, Mike (3 March 2020). "First known extraterrestrial protein possibly spotted in meteorite". Space.com. https://www.space.com/possible-extraterrestrial-protein-meteorite.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 McGeoch, Julie E. M.; McGeoch, Malcolm W. (29 June 2021). "Structural organization of space polymers". Physics of Fluids 33 (6). doi:10.1063/5.0054860. https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0054860. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McGeoch, J.E.M.; McGeoch, M.W. (21 July 2014). "Polymer Amide as an Early Topology". PLOS One 9 (7): e103036. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103036. PMID 25048204. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j3036M.

- ↑ McGeoch, J.E.M.; McGeoch, M.W. (11 September 2007). "Entrapment of water by subunit c of ATP synthase". Journal of the Royal Society Interface 5 (20): 311–318. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.1146. PMID 17848362.

- ↑ McGeoch, J.E.M.; McGeoch, M.W. (2015). "Polymer amide in the Allende and Murchison meteorites.". Meteoritics & Planetary Science 50 (12): 1971–1983. doi:10.1111/maps.12558. Bibcode: 2015M&PS...50.1971M.

- ↑ McGeoch, Julie E. M.; McGeoch, Malcolm W. (28 July 2017). "A 4641Da polymer of amino acids in Acfer-086 and Allende meteorites". arXiv:1707.09080 [astro-ph.EP].

- ↑ McGeoch, Malcolm. W.; Samoril, Tomas; Zapotok, David; McGeoch, Julie E. M. (28 July 2017). "Polymer amide as a carrier of 15N in Allende and Acfer 086 meteorites". arXiv:1811.06578 [astro-ph.EP].

External links

- First known extraterrestrial protein found (video; 4:25) on YouTube, 3 March 2020.

- First possible extraterrestrial protein found (video; 2:33) on YouTube, 2 March 2020.

- "Spreading seeds of life". Harvard University – the Harvard Gazette Journal. 8 July 2019. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/07/harvard-study-suggests-asteroids-might-play-key-role-in-spreading-life/.

- "What if life did not originate on Earth?", Isaac Chotiner & Gary Ruvkun, The New Yorker, 8 July 2019.

|