Biology:Cnidaria

| Cnidaria | |

|---|---|

| |

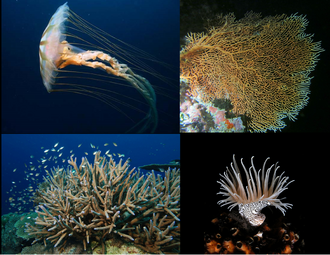

Four examples of cnidaria (clockwise, from top left):

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria Hatschek, 1888 |

| Type species | |

| Nematostella vectensis[4] | |

| Subphyla and classes[3] | |

| |

Cnidaria (/nɪˈdɛəriə, naɪ-/)[5] is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species[6] of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), including jellyfish, hydroids, sea anemone, corals and some of the smallest marine parasites. Their distinguishing features are a decentralized nervous system distributed throughout a gelatinous body and the presence of cnidocytes or cnidoblasts, specialized cells with ejectable flagella used mainly for envenomation and capturing prey. Their bodies consist of mesoglea, a non-living jelly-like substance, sandwiched between two layers of epithelium that are mostly one cell thick.

Cnidarians mostly have two basic body forms: swimming medusae and sessile polyps, both of which are radially symmetrical with mouths surrounded by tentacles that bear cnidocytes. Both forms have a single orifice and body cavity that are used for digestion and respiration. Many cnidarian species produce colonies that are single organisms composed of medusa-like or polyp-like zooids, or both (hence they are trimorphic). Cnidarians' activities are coordinated by a decentralized nerve net and simple receptors. Several free-swimming species of Cubozoa and Scyphozoa possess balance-sensing statocysts, and some have simple eyes. Not all cnidarians reproduce sexually, but many species have complex life cycles of asexual polyp stages and sexual medusae stages. Some, however, omit either the polyp or the medusa stage, and the parasitic classes evolved to have neither form.

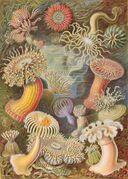

Cnidarians were formerly grouped with ctenophores in the phylum Coelenterata, but increasing awareness of their differences caused them to be placed in separate phyla.[7] Cnidarians are classified into four main groups: the almost wholly sessile Anthozoa (sea anemones, corals, sea pens); swimming Scyphozoa (jellyfish); Cubozoa (box jellies); and Hydrozoa (a diverse group that includes all the freshwater cnidarians as well as many marine forms, and which has both sessile members, such as Hydra, and colonial swimmers, such as the Portuguese man o' war). Staurozoa have recently been recognised as a class in their own right rather than a sub-group of Scyphozoa, and the highly derived parasitic Myxozoa and Polypodiozoa were firmly recognized as cnidarians only in 2007.[8]

Most cnidarians prey on organisms ranging in size from plankton to animals several times larger than themselves, but many obtain much of their nutrition from dinoflagellates, and a few are parasites. Many are preyed on by other animals including starfish, sea slugs, fish, turtles, and even other cnidarians. Many scleractinian corals—which form the structural foundation for coral reefs—possess polyps that are filled with symbiotic photo-synthetic zooxanthellae. While reef-forming corals are almost entirely restricted to warm and shallow marine waters, other cnidarians can be found at great depths, in polar regions, and in freshwater.

Cnidarians are a very ancient phylum, with fossils having been found in rocks formed about 580 million years ago during the Ediacaran period, preceding the Cambrian Explosion. Other fossils show that corals may have been present shortly before 490 million years ago and diversified a few million years later. Molecular clock analysis of mitochondrial genes suggests an even older age for the crown group of cnidarians, estimated around 741 million years ago, almost 200 million years before the Cambrian period, as well as before any fossils.[9] Recent phylogenetic analyses support monophyly of cnidarians, as well as the position of cnidarians as the sister group of bilaterians.[10]

Distinguishing features

Cnidarians form a phylum of animals that are more complex than sponges, about as complex as ctenophores (comb jellies), and less complex than bilaterians, which include almost all other animals. Both cnidarians and ctenophores are more complex than sponges as they have: cells bound by inter-cell connections and carpet-like basement membranes; muscles; nervous systems; and some have sensory organs. Cnidarians are distinguished from all other animals by having cnidocytes that fire harpoon-like structures that are mainly used to capture prey. In some species, cnidocytes can also be used as anchors.[11] Cnidarians are also distinguished by the fact that they have only one opening in their body for ingestion and excretion i.e. they do not have a separate mouth and anus.

Like sponges and ctenophores, cnidarians have two main layers of cells that sandwich a middle layer of jelly-like material, which is called the mesoglea in cnidarians; more complex animals have three main cell layers and no intermediate jelly-like layer. Hence, cnidarians and ctenophores have traditionally been labelled diploblastic, along with sponges.[11][12] However, both cnidarians and ctenophores have a type of muscle that, in more complex animals, arises from the middle cell layer.[13] As a result, some recent text books classify ctenophores as triploblastic,[12]:182–195 and it has been suggested that cnidarians evolved from triploblastic ancestors.[13]

| Sponges[12]:76–97[14] | Cnidarians[11][12] | Ctenophores[11][12]:182–195 | Bilateria[11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cnidocytes | No | Yes | No | |

| Colloblasts | No | Yes | No | |

| Digestive and circulatory organs | No | Yes | ||

| Number of main cell layers | Two, with jelly-like layer between them | Two | Two | Three |

| Cells in each layer bound together | cell-adhesion molecules, but no basement membranes except Homoscleromorpha.[15] | inter-cell connections; basement membranes | ||

| Sensory organs | No | Yes | ||

| Number of cells in middle "jelly" layer | Many | Few | (Not applicable) | |

| Cells in outer layers can move inwards and change functions | Yes | No | (Not applicable) | |

| Nervous system | No | Yes, simple | Simple to complex | |

| Muscles | None | Mostly epitheliomuscular | Mostly myoepithelial | Mostly myocytes |

Description

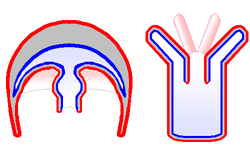

Basic body forms

Most adult cnidarians appear as either free-swimming medusae or sessile polyps, and many hydrozoans species are known to alternate between the two forms.

Both are radially symmetrical, like a wheel and a tube respectively. Since these animals have no heads, their ends are described as "oral" (nearest the mouth) and "aboral" (furthest from the mouth).

Most have fringes of tentacles equipped with cnidocytes around their edges, and medusae generally have an inner ring of tentacles around the mouth. Some hydroids may consist of colonies of zooids that serve different purposes, such as defense, reproduction and catching prey. The mesoglea of polyps is usually thin and often soft, but that of medusae is usually thick and springy, so that it returns to its original shape after muscles around the edge have contracted to squeeze water out, enabling medusae to swim by a sort of jet propulsion.[12]

Skeletons

In medusae the only supporting structure is the mesoglea. Hydra and most sea anemones close their mouths when they are not feeding, and the water in the digestive cavity then acts as a hydrostatic skeleton, rather like a water-filled balloon. Other polyps such as Tubularia use columns of water-filled cells for support. Sea pens stiffen the mesoglea with calcium carbonate spicules and tough fibrous proteins, rather like sponges.[12]

In some colonial polyps, a chitinous epidermis gives support and some protection to the connecting sections and to the lower parts of individual polyps. Stony corals secrete massive calcium carbonate exoskeletons. A few polyps collect materials such as sand grains and shell fragments, which they attach to their outsides. Some colonial sea anemones stiffen the mesoglea with sediment particles.[12]

Main cell layers

Cnidaria are diploblastic animals; in other words, they have two main cell layers, while more complex animals are triploblasts having three main layers. The two main cell layers of cnidarians form epithelia that are mostly one cell thick, and are attached to a fibrous basement membrane, which they secrete. They also secrete the jelly-like mesoglea that separates the layers. The layer that faces outwards, known as the ectoderm ("outside skin"), generally contains the following types of cells:[11]

- Epitheliomuscular cells whose bodies form part of the epithelium but whose bases extend to form muscle fibers in parallel rows.[12]: 103–104 The fibers of the outward-facing cell layer generally run at right angles to the fibers of the inward-facing one. In Anthozoa (anemones, corals, etc.) and Scyphozoa (jellyfish), the mesoglea also contains some muscle cells.[12]

- Cnidocytes, the harpoon-like "nettle cells" that give the phylum Cnidaria its name. These appear between or sometimes on top of the muscle cells.[11]

- Nerve cells. Sensory cells appear between or sometimes on top of the muscle cells,[11] and communicate via synapses (gaps across which chemical signals flow) with motor nerve cells, which lie mostly between the bases of the muscle cells.[12] Some form a simple nerve net.

- Interstitial cells, which are unspecialized and can replace lost or damaged cells by transforming into the appropriate types. These are found between the bases of muscle cells.[11]

In addition to epitheliomuscular, nerve and interstitial cells, the inward-facing gastroderm ("stomach skin") contains gland cells that secrete digestive enzymes. In some species it also contains low concentrations of cnidocytes, which are used to subdue prey that is still struggling.[11][12]

The mesoglea contains small numbers of amoeba-like cells,[12] and muscle cells in some species.[11] However, the number of middle-layer cells and types are much lower than in sponges.[12]

Polymorphism

Polymorphism refers to the occurrence of structurally and functionally more than two different types of individuals within the same organism. It is a characteristic feature of Cnidarians, particularly the polyp and medusa forms, or of zooids within colonial organisms like those in Hydrozoa.[16] In Hydrozoans, colonial individuals arising from individuals zooids will take on separate tasks.[17] For example, in Obelia there are feeding individuals, the gastrozooids; the individuals capable of asexual reproduction only, the gonozooids, blastostyles and free-living or sexually reproducing individuals, the medusae.

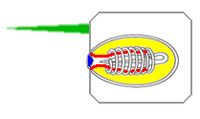

Cnidocytes

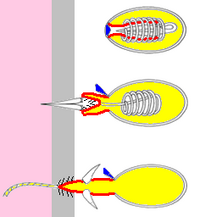

These "nettle cells" function as harpoons, since their payloads remain connected to the bodies of the cells by threads. Three types of cnidocytes are known:[11][12]

Operculum (lid)

"Finger" that turns inside out

/ / / Barbs

Venom

Victim's skin

Victim's tissues

- Nematocysts inject venom into prey, and usually have barbs to keep them embedded in the victims. Most species have nematocysts.[11]

- Spirocysts do not penetrate the victim or inject venom, but entangle it by means of small sticky hairs on the thread.

- Ptychocysts are not used for prey capture — instead the threads of discharged ptychocysts are used for building protective tubes in which their owners live. Ptychocysts are found only in the order Ceriantharia, tube anemones.[12]

The main components of a cnidocyte are:[11][12]

- A cilium (fine hair) which projects above the surface and acts as a trigger. Spirocysts do not have cilia.

- A tough capsule, the cnida, which houses the thread, its payload and a mixture of chemicals that may include venom or adhesives or both. ("cnida" is derived from the Greek word κνίδη, which means "nettle"[18])

- A tube-like extension of the wall of the cnida that points into the cnida, like the finger of a rubber glove pushed inwards. When a cnidocyte fires, the finger pops out. If the cell is a venomous nematocyte, the "finger"'s tip reveals a set of barbs that anchor it in the prey.

- The thread, which is an extension of the "finger" and coils round it until the cnidocyte fires. The thread is usually hollow and delivers chemicals from the cnida to the target.

- An operculum (lid) over the end of the cnida. The lid may be a single hinged flap or three flaps arranged like slices of pie.

- The cell body, which produces all the other parts.

It is difficult to study the firing mechanisms of cnidocytes as these structures are small but very complex. At least four hypotheses have been proposed:[11]

- Rapid contraction of fibers round the cnida may increase its internal pressure.

- The thread may be like a coiled spring that extends rapidly when released.

- In the case of Chironex (the "sea wasp"), chemical changes in the cnida's contents may cause them to expand rapidly by polymerization.

- Chemical changes in the liquid in the cnida make it a much more concentrated solution, so that osmotic pressure forces water in very rapidly to dilute it. This mechanism has been observed in nematocysts of the class Hydrozoa, sometimes producing pressures as high as 140 atmospheres, similar to that of scuba air tanks, and fully extending the thread in as little as 2 milliseconds (0.002 second).[12]

Cnidocytes can only fire once, and about 25% of a hydra's nematocysts are lost from its tentacles when capturing a brine shrimp. Used cnidocytes have to be replaced, which takes about 48 hours. To minimise wasteful firing, two types of stimulus are generally required to trigger cnidocytes: nearby sensory cells detect chemicals in the water, and their cilia respond to contact. This combination prevents them from firing at distant or non-living objects. Groups of cnidocytes are usually connected by nerves and, if one fires, the rest of the group requires a weaker minimum stimulus than the cells that fire first.[11][12]

Locomotion

File:Chrysaora quinquecirrha-Sea nettle (jellyfish).ogg Medusae swim by a form of jet propulsion: muscles, especially inside the rim of the bell, squeeze water out of the cavity inside the bell, and the springiness of the mesoglea powers the recovery stroke. Since the tissue layers are very thin, they provide too little power to swim against currents and just enough to control movement within currents.[12]

Hydras and some sea anemones can move slowly over rocks and sea or stream beds by various means: creeping like snails, crawling like inchworms, or by somersaulting. A few can swim clumsily by waggling their bases.[12]

Nervous system and senses

Cnidarians are generally thought to have no brains or even central nervous systems. However, they do have integrative areas of neural tissue that could be considered some form of centralization. Most of their bodies are innervated by decentralized nerve nets that control their swimming musculature and connect with sensory structures, though each clade has slightly different structures.[19] These sensory structures, usually called rhopalia, can generate signals in response to various types of stimuli such as light, pressure, and much more. Medusa usually have several of them around the margin of the bell that work together to control the motor nerve net, that directly innervates the swimming muscles. Most Cnidarians also have a parallel system. In scyphozoans, this takes the form of a diffuse nerve net, which has modulatory effects on the nervous system.[20] As well as forming the "signal cables" between sensory neurons and motoneurons, intermediate neurons in the nerve net can also form ganglia that act as local coordination centers. Communication between nerve cells can occur by chemical synapses or gap junctions in hydrozoans, though gap junctions are not present in all groups. Cnidarians have many of the same neurotransmitters as bilaterians, including chemicals such as glutamate, GABA, and acetylcholine.[21] Serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, octopamine, histamine, and acetylcholine, on the other hand, are absent.[22]

This structure ensures that the musculature is excited rapidly and simultaneously, and can be directly stimulated from any point on the body, and it also is better able to recover after injury.[19][20]

Medusae and complex swimming colonies such as siphonophores and chondrophores sense tilt and acceleration by means of statocysts, chambers lined with hairs which detect the movements of internal mineral grains called statoliths. If the body tilts in the wrong direction, the animal rights itself by increasing the strength of the swimming movements on the side that is too low. Most species have ocelli ("simple eyes"), which can detect sources of light. However, the agile box jellyfish are unique among Medusae because they possess four kinds of true eyes that have retinas, corneas and lenses.[23] Although the eyes probably do not form images, Cubozoa can clearly distinguish the direction from which light is coming as well as negotiate around solid-colored objects.[11][23]

Feeding and excretion

Cnidarians feed in several ways: predation, absorbing dissolved organic chemicals, filtering food particles out of the water, obtaining nutrients from symbiotic algae within their cells, and parasitism. Most obtain the majority of their food from predation but some, including the corals Hetroxenia and Leptogorgia, depend almost completely on their endosymbionts and on absorbing dissolved nutrients.[11] Cnidaria give their symbiotic algae carbon dioxide, some nutrients, and protection against predators.[12]

Predatory species use their cnidocytes to poison or entangle prey, and those with venomous nematocysts may start digestion by injecting digestive enzymes. The "smell" of fluids from wounded prey makes the tentacles fold inwards and wipe the prey off into the mouth. In medusae the tentacles round the edge of the bell are often short and most of the prey capture is done by "oral arms", which are extensions of the edge of the mouth and are often frilled and sometimes branched to increase their surface area. Medusae often trap prey or suspended food particles by swimming upwards, spreading their tentacles and oral arms and then sinking. In species for which suspended food particles are important, the tentacles and oral arms often have rows of cilia whose beating creates currents that flow towards the mouth, and some produce nets of mucus to trap particles.[11] Their digestion is both intra and extracellular.

Once the food is in the digestive cavity, gland cells in the gastroderm release enzymes that reduce the prey to slurry, usually within a few hours. This circulates through the digestive cavity and, in colonial cnidarians, through the connecting tunnels, so that gastroderm cells can absorb the nutrients. Absorption may take a few hours, and digestion within the cells may take a few days. The circulation of nutrients is driven by water currents produced by cilia in the gastroderm or by muscular movements or both, so that nutrients reach all parts of the digestive cavity.[12] Nutrients reach the outer cell layer by diffusion or, for animals or zooids such as medusae which have thick mesogleas, are transported by mobile cells in the mesoglea.[11]

Indigestible remains of prey are expelled through the mouth. The main waste product of cells' internal processes is ammonia, which is removed by the external and internal water currents.[12]

Respiration

There are no respiratory organs, and both cell layers absorb oxygen from and expel carbon dioxide into the surrounding water. When the water in the digestive cavity becomes stale it must be replaced, and nutrients that have not been absorbed will be expelled with it. Some Anthozoa have ciliated grooves on their tentacles, allowing them to pump water out of and into the digestive cavity without opening the mouth. This improves respiration after feeding and allows these animals, which use the cavity as a hydrostatic skeleton, to control the water pressure in the cavity without expelling undigested food.[11]

Cnidaria that carry photosynthetic symbionts may have the opposite problem, an excess of oxygen, which may prove toxic. The animals produce large quantities of antioxidants to neutralize the excess oxygen.[11]

Regeneration

All cnidarians can regenerate, allowing them to recover from injury and to reproduce asexually. Medusae have limited ability to regenerate, but polyps can do so from small pieces or even collections of separated cells. This enables corals to recover even after apparently being destroyed by predators.[11]

Reproduction

Sexual

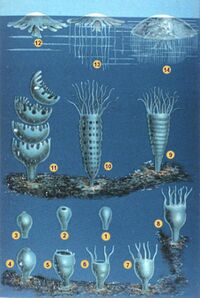

Cnidarian sexual reproduction often involves a complex life cycle with both polyp and medusa stages. For example, in Scyphozoa (jellyfish) and Cubozoa (box jellies) a larva swims until it finds a good site, and then becomes a polyp. This grows normally but then absorbs its tentacles and splits horizontally into a series of disks that become juvenile medusae, a process called strobilation. The juveniles swim off and slowly grow to maturity, while the polyp re-grows and may continue strobilating periodically. The adult medusae have gonads in the gastroderm, and these release ova and sperm into the water in the breeding season.[11][12]

This phenomenon of succession of differently organized generations (one asexually reproducing, sessile polyp, followed by a free-swimming medusa or a sessile polyp that reproduces sexually)[24] is sometimes called "alternation of asexual and sexual phases" or "metagenesis", but should not be confused with the alternation of generations as found in plants.

Shortened forms of this life cycle are common, for example some oceanic scyphozoans omit the polyp stage completely, and cubozoan polyps produce only one medusa. Hydrozoa have a variety of life cycles. Some have no polyp stages and some (e.g. hydra) have no medusae. In some species, the medusae remain attached to the polyp and are responsible for sexual reproduction; in extreme cases these reproductive zooids may not look much like medusae. Meanwhile, life cycle reversal, in which polyps are formed directly from medusae without the involvement of sexual reproduction process, was observed in both Hydrozoa (Turritopsis dohrnii[25] and Laodicea undulata[26]) and Scyphozoa (Aurelia sp.1[27]). Anthozoa have no medusa stage at all and the polyps are responsible for sexual reproduction.[11]

Spawning is generally driven by environmental factors such as changes in the water temperature, and their release is triggered by lighting conditions such as sunrise, sunset or the phase of the moon. Many species of Cnidaria may spawn simultaneously in the same location, so that there are too many ova and sperm for predators to eat more than a tiny percentage — one famous example is the Great Barrier Reef, where at least 110 corals and a few non-cnidarian invertebrates produce enough gametes to turn the water cloudy. These mass spawnings may produce hybrids, some of which can settle and form polyps, but it is not known how long these can survive. In some species the ova release chemicals that attract sperm of the same species.[11]

The fertilized eggs develop into larvae by dividing until there are enough cells to form a hollow sphere (blastula) and then a depression forms at one end (gastrulation) and eventually becomes the digestive cavity. However, in cnidarians the depression forms at the end further from the yolk (at the animal pole), while in bilaterians it forms at the other end (vegetal pole).[12] The larvae, called planulae, swim or crawl by means of cilia.[11] They are cigar-shaped but slightly broader at the "front" end, which is the aboral, vegetal-pole end and eventually attaches to a substrate if the species has a polyp stage.[12]

Anthozoan larvae either have large yolks or are capable of feeding on plankton, and some already have endosymbiotic algae that help to feed them. Since the parents are immobile, these feeding capabilities extend the larvae's range and avoid overcrowding of sites. Scyphozoan and hydrozoan larvae have little yolk and most lack endosymbiotic algae, and therefore have to settle quickly and metamorphose into polyps. Instead, these species rely on their medusae to extend their ranges.[12]

Asexual

All known cnidaria can reproduce asexually by various means, in addition to regenerating after being fragmented. Hydrozoan polyps only bud, while the medusae of some hydrozoans can divide down the middle. Scyphozoan polyps can both bud and split down the middle. In addition to both of these methods, Anthozoa can split horizontally just above the base. Asexual reproduction makes the daughter cnidarian a clone of the adult.[11][12]

DNA repair

Two classical DNA repair pathways, nucleotide excision repair and base excision repair, are present in hydra,[28] and these repair pathways facilitate unhindered reproduction. The identification of these pathways in hydra is based, in part, on the presence in the hydra genome of genes homologous to genes in other genetically well studied species that have been demonstrated to play key roles in these DNA repair pathways.[28]

Classification

Cnidarians were for a long time grouped with Ctenophores in the phylum Coelenterata, but increasing awareness of their differences caused them to be placed in separate phyla. Modern cnidarians are generally classified into four main classes:[11] sessile Anthozoa (sea anemones, corals, sea pens); swimming Scyphozoa (jellyfish) and Cubozoa (box jellies); and Hydrozoa, a diverse group that includes all the freshwater cnidarians as well as many marine forms, and has both sessile members such as Hydra and colonial swimmers such as the Portuguese Man o' War. Staurozoa have recently been recognised as a class in their own right rather than a sub-group of Scyphozoa, and the parasitic Myxozoa and Polypodiozoa are now recognized as highly derived cnidarians rather than more closely related to the bilaterians.[8][29]

| Hydrozoa | Scyphozoa | Cubozoa | Anthozoa | Myxozoa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of species[30] | 3,600 | 228 | 42 | 6,100 | 1300 |

| Examples | Hydra, siphonophores | Jellyfish | Box jellies | Sea anemones, corals, sea pens | Myxobolus cerebralis |

| Cells found in mesoglea | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Nematocysts in exodermis | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Medusa phase in life cycle | In some species | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Number of medusae produced per polyp | Many | Many | One | (not applicable) |

Stauromedusae, small sessile cnidarians with stalks and no medusa stage, have traditionally been classified as members of the Scyphozoa, but recent research suggests they should be regarded as a separate class, Staurozoa.[31]

The Myxozoa, microscopic parasites, were first classified as protozoans.[32] Research then found that Polypodium hydriforme, a non-Myxozoan parasite within the egg cells of sturgeon, is closely related to the Myxozoa and suggested that both Polypodium and the Myxozoa were intermediate between cnidarians and bilaterian animals.[33] More recent research demonstrates that the previous identification of bilaterian genes reflected contamination of the Myxozoan samples by material from their host organism, and they are now firmly identified as heavily derived cnidarians, and more closely related to Hydrozoa and Scyphozoa than to Anthozoa.[8][29][34][35]

Some researchers classify the extinct conulariids as cnidarians, while others propose that they form a completely separate phylum.[36]

Current classification according to the World Register of Marine Species:

- class Anthozoa Ehrenberg, 1834

- subclass Ceriantharia Perrier, 1893 — Tube-dwelling anemones

- subclass Hexacorallia Haeckel, 1896 — stony corals

- subclass Octocorallia Haeckel, 1866 — soft corals and sea fans

- class Cubozoa Werner, 1973 — box jellies

- class Hydrozoa Owen, 1843 — hydrozoans (fire corals, hydroids, hydroid jellyfishes, siphonophores...)

- class Myxozoa Grassé, 1970 — obligate parasites

- class Polypodiozoa Raikova, 1994 — (uncertain status)

- class Scyphozoa Goette, 1887 — "true" jellyfishes

- class Staurozoa Marques & Collins, 2004 — stalked jellyfishes

Sea anemones (Actinaria, part of Hexacorallia)

Coral Acropora muricata (Scleractinia, part of Hexacorallia)

Sea fan Gorgonia ventalina (Alcyonacea, part of Octocorallia)

Box jellyfish Carybdea branchi (Cubozoa)

Siphonophore Physalia physalis (Hydrozoa)

Jellyfish Phyllorhiza punctata (Scyphozoa)

Stalked jelly Haliclystus antarcticus (Staurozoa)

Ecology

Many cnidarians are limited to shallow waters because they depend on endosymbiotic algae for much of their nutrients. The life cycles of most have polyp stages, which are limited to locations that offer stable substrates. Nevertheless, major cnidarian groups contain species that have escaped these limitations. Hydrozoans have a worldwide range: some, such as Hydra, live in freshwater; Obelia appears in the coastal waters of all the oceans; and Liriope can form large shoals near the surface in mid-ocean. Among anthozoans, a few scleractinian corals, sea pens and sea fans live in deep, cold waters, and some sea anemones inhabit polar seabeds while others live near hydrothermal vents over 10 km (33,000 ft) below sea-level. Reef-building corals are limited to tropical seas between 30°N and 30°S with a maximum depth of 46 m (151 ft), temperatures between 20 and 28 °C (68 and 82 °F), high salinity, and low carbon dioxide levels. Stauromedusae, although usually classified as jellyfish, are stalked, sessile animals that live in cool to Arctic waters.[37] Cnidarians range in size from a mere handful of cells for the parasitic myxozoans[29] through Hydra's length of 5–20 mm (1⁄4–3⁄4 in),[38] to the Lion's mane jellyfish, which may exceed 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in diameter and 75 m (246 ft) in length.[39]

Prey of cnidarians ranges from plankton to animals several times larger than themselves.[37][40] Some cnidarians are parasites, mainly on jellyfish but a few are major pests of fish.[37] Others obtain most of their nourishment from endosymbiotic algae or dissolved nutrients.[11] Predators of cnidarians include: sea slugs, flatworms and comb jellies, which can incorporate nematocysts into their own bodies for self-defense (nematocysts used by cnidarian predators are referred to as kleptocnidae);[41][42][43] starfish, notably the crown of thorns starfish, which can devastate corals;[37] butterfly fish and parrot fish, which eat corals;[44] and marine turtles, which eat jellyfish.[39] Some sea anemones and jellyfish have a symbiotic relationship with some fish; for example clownfish live among the tentacles of sea anemones, and each partner protects the other against predators.[37]

Coral reefs form some of the world's most productive ecosystems. Common coral reef cnidarians include both Anthozoans (hard corals, octocorals, anemones) and Hydrozoans (fire corals, lace corals). The endosymbiotic algae of many cnidarian species are very effective primary producers, in other words converters of inorganic chemicals into organic ones that other organisms can use, and their coral hosts use these organic chemicals very efficiently. In addition, reefs provide complex and varied habitats that support a wide range of other organisms.[45] Fringing reefs just below low-tide level also have a mutually beneficial relationship with mangrove forests at high-tide level and seagrass meadows in between: the reefs protect the mangroves and seagrass from strong currents and waves that would damage them or erode the sediments in which they are rooted, while the mangroves and seagrass protect the coral from large influxes of silt, fresh water and pollutants. This additional level of variety in the environment is beneficial to many types of coral reef animals, which for example may feed in the sea grass and use the reefs for protection or breeding.[46]

Evolutionary history

Fossil record

The earliest widely accepted animal fossils are rather modern-looking cnidarians, possibly from around 580 million years ago, although fossils from the Doushantuo Formation can only be dated approximately.[47] The identification of some of these as embryos of animals has been contested, but other fossils from these rocks strongly resemble tubes and other mineralized structures made by corals.[48] Their presence implies that the cnidarian and bilaterian lineages had already diverged.[49] Although the Ediacaran fossil Charnia used to be classified as a jellyfish or sea pen,[50] more recent study of growth patterns in Charnia and modern cnidarians has cast doubt on this hypothesis,[51][52] leaving the Canadian polyp Haootia and the British Auroralumina as the only recognized cnidarian body fossils from the Ediacaran. Auroralumina is the earliest known animal predator.[53] Few fossils of cnidarians without mineralized skeletons are known from more recent rocks, except in lagerstätten that preserved soft-bodied animals.[54]

A few mineralized fossils that resemble corals have been found in rocks from the Cambrian period, and corals diversified in the Early Ordovician.[54] These corals, which were wiped out in the Permian–Triassic extinction event about 252 million years ago,[54] did not dominate reef construction since sponges and algae also played a major part.[55] During the Mesozoic era rudist bivalves were the main reef-builders, but they were wiped out in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago,[56] and since then the main reef-builders have been scleractinian corals.[54]

Family tree

It is difficult to reconstruct the early stages in the evolutionary "family tree" of animals using only morphology (their shapes and structures), because the large differences between Porifera (sponges), Cnidaria plus Ctenophora (comb jellies), Placozoa and Bilateria (all the more complex animals) make comparisons difficult. Hence reconstructions now rely largely or entirely on molecular phylogenetics, which groups organisms according to similarities and differences in their biochemistry, usually in their DNA or RNA.[57]

It is now generally thought that the Calcarea (sponges with calcium carbonate spicules) are more closely related to Cnidaria, Ctenophora (comb jellies) and Bilateria (all the more complex animals) than they are to the other groups of sponges.[58][59][60] In 1866 it was proposed that Cnidaria and Ctenophora were more closely related to each other than to Bilateria and formed a group called Coelenterata ("hollow guts"), because Cnidaria and Ctenophora both rely on the flow of water in and out of a single cavity for feeding, excretion and respiration. In 1881, it was proposed that Ctenophora and Bilateria were more closely related to each other, since they shared features that Cnidaria lack, for example muscles in the middle layer (mesoglea in Ctenophora, mesoderm in Bilateria). However more recent analyses indicate that these similarities are rather vague, and the current view, based on molecular phylogenetics, is that Cnidaria and Bilateria are more closely related to each other than either is to Ctenophora. This grouping of Cnidaria and Bilateria has been labelled "Planulozoa" because it suggests that the earliest Bilateria were similar to the planula larvae of Cnidaria.[2][61]

Within the Cnidaria, the Anthozoa (sea anemones and corals) are regarded as the sister-group of the rest, which suggests that the earliest cnidarians were sessile polyps with no medusa stage. However, it is unclear how the other groups acquired the medusa stage, since Hydrozoa form medusae by budding from the side of the polyp while the other Medusozoa do so by splitting them off from the tip of the polyp. The traditional grouping of Scyphozoa included the Staurozoa, but morphology and molecular phylogenetics indicate that Staurozoa are more closely related to Cubozoa (box jellies) than to other "Scyphozoa". Similarities in the double body walls of Staurozoa and the extinct Conulariida suggest that they are closely related.[2][62]

However, in 2005 Katja Seipel and Volker Schmid suggested that cnidarians and ctenophores are simplified descendants of triploblastic animals, since ctenophores and the medusa stage of some cnidarians have striated muscle, which in bilaterians arises from the mesoderm. They did not commit themselves on whether bilaterians evolved from early cnidarians or from the hypothesized triploblastic ancestors of cnidarians.[13]

In molecular phylogenetics analyses from 2005 onwards, important groups of developmental genes show the same variety in cnidarians as in chordates.[63] In fact cnidarians, and especially anthozoans (sea anemones and corals), retain some genes that are present in bacteria, protists, plants and fungi but not in bilaterians.[64]

The mitochondrial genome in the medusozoan cnidarians, unlike those in other animals, is linear with fragmented genes.[65] The reason for this difference is unknown.

Interaction with humans

Jellyfish stings killed about 1,500 people in the 20th century,[66] and cubozoans are particularly dangerous. On the other hand, some large jellyfish are considered a delicacy in East and Southeast Asia. Coral reefs have long been economically important as providers of fishing grounds, protectors of shore buildings against currents and tides, and more recently as centers of tourism. However, they are vulnerable to over-fishing, mining for construction materials, pollution, and damage caused by tourism.

Beaches protected from tides and storms by coral reefs are often the best places for housing in tropical countries. Reefs are an important food source for low-technology fishing, both on the reefs themselves and in the adjacent seas.[67] However, despite their great productivity, reefs are vulnerable to over-fishing, because much of the organic carbon they produce is exhaled as carbon dioxide by organisms at the middle levels of the food chain and never reaches the larger species that are of interest to fishermen.[45] Tourism centered on reefs provides much of the income of some tropical islands, attracting photographers, divers and sports fishermen. However, human activities damage reefs in several ways: mining for construction materials; pollution, including large influxes of fresh water from storm drains; commercial fishing, including the use of dynamite to stun fish and the capture of young fish for aquariums; and tourist damage caused by boat anchors and the cumulative effect of walking on the reefs.[67] Coral, mainly from the Pacific Ocean has long been used in jewellery, and demand rose sharply in the 1980s.[68]

Some large jellyfish species of the Rhizostomeae order are commonly consumed in Japan , Korea and Southeast Asia.[69][70][71] In parts of the range, fishing industry is restricted to daylight hours and calm conditions in two short seasons, from March to May and August to November.[71] The commercial value of jellyfish food products depends on the skill with which they are prepared, and "Jellyfish Masters" guard their trade secrets carefully. Jellyfish is very low in cholesterol and sugars, but cheap preparation can introduce undesirable amounts of heavy metals.[72]

The "sea wasp" Chironex fleckeri has been described as the world's most venomous jellyfish and is held responsible for 67 deaths, although it is difficult to identify the animal as it is almost transparent. Most stingings by C. fleckeri cause only mild symptoms.[73] Seven other box jellies can cause a set of symptoms called Irukandji syndrome,[74] which takes about 30 minutes to develop,[75] and from a few hours to two weeks to disappear.[76] Hospital treatment is usually required, and there have been a few deaths.[74]

A number of the parasitic Myxozoans are commercially important pathogens in salmonid aquaculture.[77] A Scyphozoa species – Pelagia noctiluca – and a Hydrozoa – Muggiaea atlantica – have caused repeated mass mortality in salmon farms over the years around Ireland.[78] A loss valued at £1 million struck in November 2007, 20,000 died off Clare Island in 2013 and four fish farms collectively lost tens of thousands of salmon in September 2017.[78]

Notes

- ↑ Classes in Medusozoa based on "ITIS Report – Taxon: Subphylum Medusozoa". Universal Taxonomic Services. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=718920#null.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Collins, A.G. (May 2002). "Phylogeny of Medusozoa and the Evolution of Cnidarian Life Cycles". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 15 (3): 418–432. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00403.x.

- ↑ Subphyla Anthozoa and Medusozoa based on "The Taxonomicon – Taxon: Phylum Cnidaria". Universal Taxonomic Services. http://www.taxonomy.nl/Taxonomicon/TaxonTree.aspx?id=11551.

- ↑ Steele, Robert E.; Technau, Ulrich (2011-04-15). "Evolutionary crossroads in developmental biology: Cnidaria" (in en). Development 138 (8): 1447–1458. doi:10.1242/dev.048959. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 21389047.

- ↑ cnidaria (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, September 2005, http://oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=cnidaria (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species". http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=browser&id%5B%5D=2&id%5B%5D=1267#focus.

- ↑ Dunn, Casey W.; Leys, Sally P.; Haddock, Steven H.D. (May 2015). "The hidden biology of sponges and ctenophores". Trends in Ecology & Evolution 30 (5): 282–291. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2015.03.003. PMID 25840473.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 E. Jímenez-Guri (July 2007). "Buddenbrockia is a cnidarian worm". Science 317 (116): 116–118. doi:10.1126/science.1142024. PMID 17615357. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..116J.

- ↑ "Estimation of divergence times in cnidarian evolution based on mitochondrial protein-coding genes and the fossil record.". Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution 62 (1): 329–45. January 2012. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.10.008. PMID 22040765.

- ↑ "Phylogenomic Analyses Support Traditional Relationships within Cnidaria.". PLOS ONE 10 (10): e0139068. 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139068. PMID 26465609. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1039068Z.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 11.17 11.18 11.19 11.20 11.21 11.22 11.23 11.24 11.25 11.26 11.27 11.28 11.29 11.30 Hinde, R.T. (1998). "The Cnidaria and Ctenophora". in Anderson, D.T.. Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 28–57. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 12.24 12.25 12.26 12.27 12.28 12.29 12.30 12.31 12.32 Ruppert, E.E.; Fox, R.S.; Barnes, R.D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7 ed.). Brooks / Cole. pp. 111–124. ISBN 978-0-03-025982-1. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780030259821/page/111.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Seipel, K.; Schmid, V. (June 2005). "Evolution of striated muscle: Jellyfish and the origin of triploblasty". Developmental Biology 282 (1): 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.032. PMID 15936326.

- ↑ Bergquist, P.R. (1998). "Porifera". in Anderson, D.T.. Invertebrate Zoology. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–27. ISBN 978-0-19-551368-4.

- ↑ Exposito, J-Y.; Cluzel, C.; Garrone, R.; Lethias, C. (2002). "Evolution of collagens". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology 268 (3): 302–316. doi:10.1002/ar.10162. PMID 12382326.

- ↑ Ford, E.B. (1965). Genetic polymorphism. 164. London: Faber & Faber. 350–61. doi:10.1098/rspb.1966.0037. ISBN 978-0262060127.

- ↑ Dunn, Casey W.; Wagner, Günter P. (16 September 2006). "The evolution of colony-level development in the Siphonophora (Cnidaria:Hydrozoa)". Development Genes and Evolution 216 (12): 743–754. doi:10.1007/s00427-006-0101-8. PMID 16983540.

- ↑ Trumble, W.; Brown, L. (2002). "Cnida". Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Satterlie, Richard A. (15 April 2011). "Do jellyfish have central nervous systems?" (in en). Journal of Experimental Biology 214 (8): 1215–1223. doi:10.1242/jeb.043687. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 21430196.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Satterlie, Richard A (2002-10-01). "Neuronal control of swimming in jellyfish: a comparative story". Canadian Journal of Zoology 80 (10): 1654–1669. doi:10.1139/z02-132. ISSN 0008-4301.

- ↑ Kass-Simon, G.; Pierobon, Paola (1 January 2007). "Cnidarian chemical neurotransmission, an updated overview". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 146 (1): 9–25. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.008. PMID 17101286.

- ↑ What is a neuron? (Ctenophores, sponges and placozoans)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Jellyfish Have Human-Like Eyes". www.livescience.com. April 1, 2007. http://www.livescience.com/7243-jellyfish-human-eyes.html.

- ↑ Vernon A. Harris (1990). "Hydroids". Sessile animals of the sea shore. Springer. p. 223. ISBN 9780412337604. https://books.google.com/books?id=DbaBQm_ZQkIC&q=alternation+of+generation+&pg=PA223.

- ↑ Bavestrello (1992). "Bi-directional conversion in Turritopsis nutricula (Hydrozoa)". Scientia Marina. http://www.icm.csic.es/scimar/pdf/56/sm56n2137.pdf. Retrieved 2015-12-31.

- ↑ De Vito (2006). "Evidence of reverse development in Leptomedusae (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa): the case of Laodicea undulata (Forbes and Goodsir 1851)". Marine Biology 149 (2): 339–346. doi:10.1007/s00227-005-0182-3. Bibcode: 2006MarBi.149..339D.

- ↑ He (21 December 2015). "Life Cycle Reversal in Aurelia sp.1 (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa)". PLOS ONE 10 (12): e0145314. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145314. PMID 26690755. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1045314H.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Barve, A.; Galande, A. A.; Ghaskadbi, S. S.; Ghaskadbi, S. (2021). "DNA Repair Repertoire of the Enigmatic Hydra". Frontiers in Genetics 12: 670695. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.670695. PMID 33995496.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Schuster, Ruth (20 November 2015). "Microscopic parasitic jellyfish defy everything we know, astonish scientists". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/science/1.687159.

- ↑ Zhang, Z.-Q. (2011). "Animal biodiversity: An introduction to higher-level classification and taxonomic richness". Zootaxa 3148: 7–12. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.3. http://mapress.com/zootaxa/2011/f/zt03148p012.pdf.

- ↑ Collins, A.G.; Cartwright, P.; McFadden, C.S.; Schierwater, B. (2005). "Phylogenetic Context and Basal Metazoan Model Systems". Integrative and Comparative Biology 45 (4): 585–594. doi:10.1093/icb/45.4.585. PMID 21676805.

- ↑ Štolc, A. (1899). "Actinomyxidies, nouveau groupe de Mesozoaires parent des Myxosporidies". Bull. Int. l'Acad. Sci. Bohème 12: 1–12.

- ↑ Zrzavý, J.; Hypša, V. (April 2003). "Myxozoa, Polypodium, and the origin of the Bilateria: The phylogenetic position of "Endocnidozoa" in light of the rediscovery of Buddenbrockia". Cladistics 19 (2): 164–169. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00305.x.

- ↑ E. Jímenez-Guri; Philippe, H; Okamura, B; Holland, PW (July 2007). "Buddenbrockia is a cnidarian worm". Science 317 (116): 116–118. doi:10.1126/science.1142024. PMID 17615357. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..116J.

- ↑ Chang, E. Sally; Neuhof, Moran; Rubinstein, Nimrod D. et al. (1 December 2015). "Genomic insights into the evolutionary origin of Myxozoa within Cnidaria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (48): 14912–14917. doi:10.1073/pnas.1511468112. PMID 26627241. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..11214912C.

- ↑ "The Conulariida". University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/conulariida.html.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Shostak, S. (2006). "Cnidaria (Coelenterates)". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1038/npg.els.0004117. ISBN 978-0470016176.

- ↑ Blaise, C.; Férard, J-F. (2005). Small-scale Freshwater Toxicity Investigations: Toxicity Test Methods. Springer. p. 398. ISBN 978-1-4020-3119-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ibew5SLx2oMC&q=hydra+size+length. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Safina, C. (2007). Voyage of the Turtle: In Pursuit of the Earth's Last Dinosaur. Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8050-8318-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=dQD883dAv6YC&q=cnidaria+turtle&pg=PA154. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Cowen, R. (2000). History of Life (3 ed.). Blackwell. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-632-04444-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=qvyBS4gwPF4C&q=cnidaria+prey&pg=PA54. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Krohne, Georg (2018). "Organelle survival in a foreign organism: Hydra nematocysts in the flatworm Microstomum lineare". European Journal of Cell Biology 97 (4): 289–299. doi:10.1016/j.ejcb.2018.04.002. PMID 29661512. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0171933518300268.

- ↑ Greenwood, P. G. (2009). "Acquisition and Use of Nematocysts by Cnidarian Predators". Toxicon 54 (8): 1065–1070. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.02.029. PMID 19269306.

- ↑ Frick, K (2003). "Predator Suites and Flabellinid Nudibranch Nematocyst Complements in the Gulf of Maine". In: SF Norton (Ed). Diving for Science...2003. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (22nd Annual Scientific Diving Symposium). http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/4744. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ↑ Choat, J.H.; Bellwood, D.R. (1998). Paxton, J.R.. ed. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 209–211. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Barnes, R.S.K.; Mann, K.H. (1991). Fundamentals of Aquatic Ecology. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 217–227. ISBN 978-0-632-02983-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=mOZZlzgdTrwC&q=%22Coral+Reef%22+productivity&pg=PA227. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ↑ Hatcher, B.G.; Johannes, R.E.; Robertson, A.J. (1989). "Conservation of Shallow-water Marine Ecosystems". Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review: Volume 27. Routledge. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-08-037718-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=XpmNqFaDZ7cC&q=%22Coral+Reef%22+mangrove+%22seagrass%22&pg=PA320. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Chen, J-Y.; Oliveri, P; Li, CW et al. (25 April 2000). "Putative phosphatized embryos from the Doushantuo Formation of China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97 (9): 4457–4462. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4457. PMID 10781044. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.4457C.

- ↑ Xiao, S.; Yuan, X.; Knoll, A.H. (5 December 2000). "Eumetazoan fossils in terminal Proterozoic phosphorites?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 97 (25): 13684–13689. doi:10.1073/pnas.250491697. PMID 11095754. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...9713684X.

- ↑ Chen, J.-Y.; Oliveri, P.; Gao, F. et al. (August 2002). "Precambrian Animal Life: Probable Developmental and Adult Cnidarian Forms from Southwest China". Developmental Biology 248 (1): 182–196. doi:10.1006/dbio.2002.0714. PMID 12142030. http://www.uwm.edu/~sdornbos/PDF's/Chen%20et%20al.%202002.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-03.

- ↑ Donovan, Stephen K.; Lewis, David N. (2001). "Fossils explained 35. The Ediacaran biota". Geology Today 17 (3): 115–120. doi:10.1046/j.0266-6979.2001.00285.x.

- ↑ Antcliffe, J.B.; Brasier, M. D. (2007). "Charnia and sea pens are poles apart". Journal of the Geological Society 164 (1): 49–51. doi:10.1144/0016-76492006-080. Bibcode: 2007JGSoc.164...49A.

- ↑ Antcliffe, J.B.; Brasier, Martin D. (2007). "Charnia At 50: Developmental Models For Ediacaran Fronds". Palaeontology 51 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00738.x.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (25 July 2022). "Ancient fossil is earliest known animal predator". BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-62291954.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 "Cnidaria: Fossil Record". University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cnidariafr.html.

- ↑ Copper, P. (January 1994). "Ancient reef ecosystem expansion and collapse". Coral Reefs 13 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1007/BF00426428. Bibcode: 1994CorRe..13....3C.

- ↑ "The Rudists". University of California Museum of Paleontology. http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/rudists.php.

- ↑ Halanych, K.M. (December 2004). "The New View of Animal Phylogeny". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 35: 229–256. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.35.112202.130124. http://gump.auburn.edu/halanych/lab/Pub.pdfs/Halanych2004.pdf. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ↑ Borchiellini, C.; Manuel, M.; Alivon, E. et al. (January 2001). "Sponge paraphyly and the origin of Metazoa". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 14 (1): 171–179. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00244.x. PMID 29280585.

- ↑ Medina, M.; Collins, A.G.; Silberman, J.D.; Sogin, M.L. (August 2001). "Evaluating hypotheses of basal animal phylogeny using complete sequences of large and small subunit rRNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98 (17): 9707–9712. doi:10.1073/pnas.171316998. PMID 11504944. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...98.9707M.

- ↑ Müller, W.E.G.; Li, J.; Schröder, H.C. et al. (2007). "The unique skeleton of siliceous sponges (Porifera; Hexactinellida and Demospongiae) that evolved first from the Urmetazoa during the Proterozoic: a review". Biogeosciences 4 (2): 219–232. doi:10.5194/bg-4-219-2007. Bibcode: 2007BGeo....4..219M. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00297608/file/bg-4-219-2007.pdf.

- ↑ Wallberg, A.; Thollesson, M.; Farris, J.S.; Jondelius, U. (2004). "The phylogenetic position of the comb jellies (Ctenophora) and the importance of taxonomic sampling". Cladistics 20 (6): 558–578. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00041.x. PMID 34892961.

- ↑ Marques, A.C.; Collins, A.G. (2004). "Cladistic analysis of Medusozoa and cnidarian evolution". Invertebrate Biology 123 (1): 23–42. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2004.tb00139.x. http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=sourceget&id=38492. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ↑ Miller, D.J.; Ball, E.E.; Technau, U. (October 2005). "Cnidarians and ancestral genetic complexity in the animal kingdom". Trends in Genetics 21 (10): 536–539. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.002. PMID 16098631.

- ↑ Technau, U.; Rudd, S.; Maxwell, P (December 2005). "Maintenance of ancestral complexity and non-metazoan genes in two basal cnidarians". Trends in Genetics 21 (12): 633–639. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.09.007. PMID 16226338.

- ↑ Smith, D. R.; Kayal, E.; Yanagihara, A. A. et al. (2011). "First Complete Mitochondrial Genome Sequence from a Box Jellyfish Reveals a Highly Fragmented Linear Architecture and Insights into Telomere Evolution". Genome Biology and Evolution 4 (1): 52–58. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr127. PMID 22117085.

- ↑ Williamson, J.A.; Fenner, P.J.; Burnett, J.W.; Rifkin, J. (1996). Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals: A Medical and Biological Handbook. UNSW Press. pp. 65–68. ISBN 978-0-86840-279-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=YsZ3GryFIzEC&q=mollusc+venom+fatal&pg=PA75. Retrieved 2008-10-03.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Clark, J.R. (1998). Coastal Seas: The Conservation Challenge. Blackwell. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-632-04955-4. https://archive.org/details/coastalseasconse0000clar. Retrieved 2008-11-28. "Coral Reef productivity."

- ↑ Cronan, D.S. (1991). Marine Minerals in Exclusive Economic Zones. Springer. pp. 63–65. ISBN 978-0-412-29270-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=4g4nhd8USO8C&q=coral+jewellery&pg=PA63. Retrieved 2008-11-28.

- ↑ Kitamura, M.; Omori, M. (2010). "Synopsis of edible jellyfishes collected from Southeast Asia, with notes on jellyfish fisheries". Plankton and Benthos Research 5 (3): 106–118. doi:10.3800/pbr.5.106. ISSN 1880-8247.

- ↑ Omori, M.; Kitamura, M. (2004). "Taxonomic review of three Japanese species of edible jellyfish (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae)". Plankton Biol. Ecol. 51 (1): 36–51.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Omori, M.; Nakano, E. (May 2001). "Jellyfish fisheries in southeast Asia". Hydrobiologia 451: 19–26. doi:10.1023/A:1011879821323.

- ↑ Y-H. Peggy Hsieh; Fui-Ming Leong; Jack Rudloe (May 2001). "Jellyfish as food". Hydrobiologia 451 (1–3): 11–17. doi:10.1023/A:1011875720415.

- ↑ Greenberg, M.I.; Hendrickson, R.G.; Silverberg, M. et al. (2004). "Box Jellyfish Envenomation". Greenberg's Text-atlas of Emergency Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 875. ISBN 978-0-7817-4586-4.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Little, M.; Pereira, P.; Carrette, T.; Seymour, J. (June 2006). "Jellyfish Responsible for Irukandji Syndrome". QJM 99 (6): 425–427. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcl057. PMID 16687419.

- ↑ Barnes, J. (1964). "Cause and effect in Irukandji stingings". Medical Journal of Australia 1 (24): 897–904. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1964.tb114424.x. PMID 14172390.

- ↑ "Irukandji-like syndrome in South Florida divers". Annals of Emergency Medicine 42 (6): 763–6. December 2003. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00513-4. PMID 14634600.

- ↑ Braden, Laura M.; Rasmussen, Karina J.; Purcell, Sara L. et al. (December 19, 2017). Appleton, Judith A.. ed. "Acquired Protective Immunity in Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar against the Myxozoan Kudoa thyrsites Involves Induction of MHIIβ + CD83 + Antigen-Presenting Cells" (in en). Infection and Immunity 86 (1): e00556–17. doi:10.1128/IAI.00556-17. ISSN 0019-9567. PMID 28993459.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 O'Sullivan, Kevin (2017-10-06). "Stinger jellyfish swarms wipe out farmed salmon in west of Ireland". http://www.irishtimes.com/news/environment/stinger-jellyfish-swarms-wipe-out-farmed-salmon-in-west-of-ireland-1.3247245.

Further reading

Books

- Arai, M.N. (1997). A Functional Biology of Scyphozoa. London: Chapman & Hall [p. 316]. ISBN:0-412-45110-7.

- Ax, P. (1999). Das System der Metazoa I. Ein Lehrbuch der phylogenetischen Systematik. Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart-Jena: Gustav Fischer. ISBN:3-437-30803-3.

- Barnes, R.S.K., P. Calow, P. J. W. Olive, D. W. Golding & J. I. Spicer (2001). The invertebrates—a synthesis. Oxford: Blackwell. 3rd edition [chapter 3.4.2, p. 54]. ISBN:0-632-04761-5.

- Brusca, R.C., G.J. Brusca (2003). Invertebrates. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. 2nd edition [chapter 8, p. 219]. ISBN:0-87893-097-3.

- Dalby, A. (2003). Food in the Ancient World: from A to Z. London: Routledge.

- Moore, J.(2001). An Introduction to the Invertebrates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press [chapter 4, p. 30]. ISBN:0-521-77914-6.

- Schäfer, W. (1997). Cnidaria, Nesseltiere. In Rieger, W. (ed.) Spezielle Zoologie. Teil 1. Einzeller und Wirbellose Tiere. Stuttgart-Jena: Gustav Fischer. Spektrum Akademischer Verl., Heidelberg, 2004. ISBN:3-8274-1482-2.

- Werner, B. 4. Stamm Cnidaria. In: V. Gruner (ed.) Lehrbuch der speziellen Zoologie. Begr. von Kaestner. 2 Bde. Stuttgart-Jena: Gustav Fischer, Stuttgart-Jena. 1954, 1980, 1984, Spektrum Akad. Verl., Heidelberg-Berlin, 1993. 5th edition. ISBN:3-334-60474-8.

Journal articles

- D. Bridge, B. Schierwater, C. W. Cunningham, R. DeSalle R, L. W. Buss: Mitochondrial DNA structure and the molecular phylogeny of recent cnidaria classes. in: Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. Philadelphia USA 89.1992, p. 8750. ISSN 0097-3157

- D. Bridge, C. W. Cunningham, R. DeSalle, L. W. Buss: Class-level relationships in the phylum Cnidaria—Molecular and morphological evidence. in: Molecular biology and evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford 12.1995, p. 679. ISSN 0737-4038

- D. G. Fautin: Reproduction of Cnidaria

. in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1735. (PDF, online) ISSN 0008-4301

. in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1735. (PDF, online) ISSN 0008-4301 - G. O. Mackie: What's new in cnidarian biology?

in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1649. (PDF, online) ISSN 0008-4301

in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1649. (PDF, online) ISSN 0008-4301 - P. Schuchert: Phylogenetic analysis of the Cnidaria. in: Zeitschrift für zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. Paray, Hamburg-Berlin 31.1993, p. 161. ISSN 0044-3808

- G. Kass-Simon, A. A. Scappaticci Jr.: The behavioral and developmental physiology of nematocysts.

in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1772. (PDF, online) ISSN 0044-3808

in: Canadian Journal of Zoology. Ottawa Ont. 80.2002, p. 1772. (PDF, online) ISSN 0044-3808 - J. Zrzavý (2001). "The interrelationships of metazoan parasites: a review of phylum- and higher-level hypotheses from recent morphological and molecular phylogenetic analyses". Folia Parasitologica 48 (2): 81–103. doi:10.14411/fp.2001.013. PMID 11437135.

External links

- YouTube: Nematocysts Firing

- YouTube:My Anemone Eat Meat Defensive and feeding behaviour of sea anemone

- Cnidaria - Guide to the Marine Zooplankton of south eastern Australia, Tasmanian Aquaculture & Fisheries Institute

- A Cnidaria homepage maintained by University of California, Irvine

- Cnidaria page at Tree of Life

- Fossil Gallery: Cnidarians

- The Hydrozoa Directory

- Hexacorallians of the World

Wikidata ☰ Q25441 entry

|