Astronomy:Extreme trans-Neptunian object

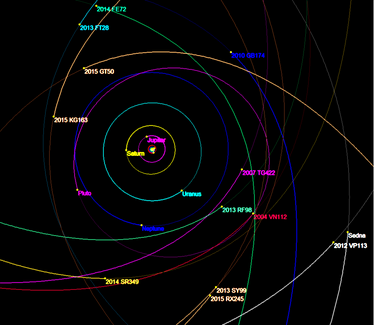

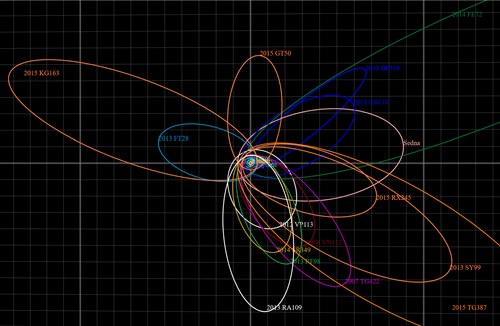

An extreme trans-Neptunian object (ETNO) is a trans-Neptunian object orbiting the Sun well beyond Neptune (30 AU) in the outermost region of the Solar System. An ETNO has a large semi-major axis of at least 150–250 AU.[1][2] The orbits of ETNOs are much less affected by the known giant planets than all other known trans-Neptunian objects. They may, however, be influenced by gravitational interactions with a hypothetical Planet Nine, shepherding these objects into similar types of orbits.[1] The known ETNOs exhibit a highly statistically significant asymmetry between the distributions of object pairs with small ascending and descending nodal distances that might be indicative of a response to external perturbations.[3][4]

ETNOs can be divided into three different subgroups. The scattered ETNOs (or extreme scattered disc objects, ESDOs) have perihelia around 38–45 AU and an exceptionally high eccentricity of more than 0.85. As with the regular scattered disc objects, they were likely formed as result of gravitational scattering by Neptune and still interact with the giant planets. The detached ETNOs (or extreme detached disc objects, EDDOs), with perihelia approximately between 40–45 and 50–60 AU, are less affected by Neptune than the scattered ETNOs, but are still relatively close to Neptune. The sednoid or inner Oort cloud objects, with perihelia beyond 50–60 AU, are too far from Neptune to be strongly influenced by it.[1]

Sednoids

Among the extreme trans-Neptunian objects are the sednoids, four objects with an outstandingly high perihelion: Sedna, 2012 VP113, Leleākūhonua, and 2023 KQ14. Sedna and 2012 VP113 are distant detached objects with perihelia greater than 70 AU. Their high perihelia keep them at a sufficient distance to avoid significant gravitational perturbations from Neptune. Previous explanations for the high perihelion of Sedna include a close encounter with an unknown planet on a distant orbit and a distant encounter with a random star or a member of the Sun's birth cluster that passed near the Solar System.[5][6][7]

Most distant objects from the Sun

[[File:Extreme transneptunian object eccentricity vs perihelion.png|thumb|350px|The chart above plots trans-Neptunian objects with a perihelion beyond Neptune (30 AU). While regular TNOs are located in the bottom left of the plot, an ETNO has a semi-major axis greater than 150–250 AU. They can be grouped by their perihelia into three distinct populations:[1]

scattered ETNOs or ESDOs (38–45 AU)

detached ETNOs or EDDOs (40–45 to 50–60 AU)

Sednoids or inner Oort cloud objects (beyond 50–60 AU)

Notable discoveries

Trujillo and Sheppard discoveries

Extreme trans-Neptunian objects discovered by astronomers Chad Trujillo and Scott S. Sheppard include:

- 2013 FT28, Longitude of perihelion aligned with Planet Nine, but well within the proposed orbit of Planet Nine, where computer modeling suggests it would be safe from gravitational kicks.[8]

- 2014 SR349, appears to be anti-aligned with Planet Nine.[8]

- 2014 FE72, an object with an orbit so extreme that it reaches about 4000 AU from the Sun in a massively-elongated ellipse – at this distance its orbit is influenced by the galactic tide and other stars.[9][10][11][12]

Outer Solar System Origins Survey

The Outer Solar System Origins Survey has discovered more extreme trans-Neptunian objects, including:[13]

- 2013 SY99, which has a lower inclination than many of the objects, and which was discussed by Michele Bannister at a March 2016 lecture hosted by the SETI Institute and later at an October 2016 AAS conference.[14][15]

- 2015 KG163, which has an orientation similar to 2013 FT28 but has a larger semi-major axis that may result in its orbit crossing Planet Nine's.

- 2015 RX245, which fits with the other anti-aligned objects.

- 2015 GT50, which is in neither the anti-aligned nor the aligned groups; instead, its orbit's orientation is at a right angle to that of the proposed Planet Nine. Its argument of perihelion is also outside the cluster of arguments of perihelion.

Since early 2016, ten more extreme trans-Neptunian objects have been discovered with orbits that have a perihelion greater than 30 AU and a semi-major axis greater than 250 AU bringing the total to sixteen (see table below for a complete list). Most TNOs have perihelia significantly beyond Neptune, which orbits 30 AU from the Sun.[16][17] Generally, TNOs with perihelia smaller than 36 AU experience strong encounters with Neptune.[18][19] Most of the ETNOs are relatively small, but currently relatively bright because they are near their closest distance to the Sun in their elliptical orbits. These are also included in the orbital diagrams and tables below.

TESS data search

Malena Rice and Gregory Laughlin applied a targeted shift-stacking search algorithm to analyze data from TESS sectors 18 and 19 looking for candidate outer Solar System objects.[20] Their search recovered known ETNOs like Sedna and produced 17 new outer Solar System body candidates located at geocentric distances in the range 80–200 AU, that need follow-up observations with ground-based telescope resources for confirmation. Early results from a survey with WHT aimed at recovering these distant TNO candidates have failed to confirm two of them.[21][22]

List

| Object | Barycentric Orbit (JD 2459600.5)[upper-alpha 2] | Orbital plane | Body | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability [28] |

Orbital period (years) |

Semimajor axis (AU) |

Perihelion (AU) |

Aphelion (AU) |

Current distance from Sun (AU) |

Eccent. | Argum. peri ω (°) |

inclin. i (°) |

Longitude of | Hv | Current mag. |

Diameter (km) | ||

| Ascending node ☊ or Ω (°) |

Perihelion ϖ=ω+Ω (°) | |||||||||||||

| Sedna | Stable | 11,400 | 485 | 76.3 | 893 | 84.5 | 0.84 | 311.3 | 11.9 | 144.2 | 95.6 | 1.3 | 20.7 | 1,000 |

| Alicanto | Stable | 5,900 | 327 | 47.3 | 608 | 48.1 | 0.86 | 326.7 | 25.6 | 66.0 | 32.7 | 6.5 | 23.5 | 200 |

| 2007 TG422 | Unstable | 11,260 | 502 | 35.6 | 969 | 38.5 | 0.93 | 285.6 | 18.6 | 112.9 | 38.4 | 6.5 | 22.5 | 200 |

| Leleākūhonua | Stable | 35,300 | 1,090 | 65.2 | 2,110 | 78.0 | 0.94 | 117.8 | 11.7 | 300.8 | 58.5 | 5.5 | 24.6 | 220 |

| 2010 GB174 | Stable | 6,600 | 342 | 48.6 | 636 | 73.1 | 0.86 | 347.1 | 21.6 | 130.9 | 118.0 | 6.5 | 25.2 | 200 |

| 2012 VP113 | Stable | 4,300 | 261 | 80.4 | 443 | 84.0 | 0.69 | 293.6 | 24.1 | 90.7 | 24.3 | 4.0 | 23.3 | 600 |

| 2013 FL28 | ? | 6,780 | 358 | 32.2 | 684 | 33.4 | 0.91 | 225.1 | 15.8 | 294.4 | 159.5 (*) | 8.0 | 23.4 | 100 |

| 2013 FT28 | Metastable | 5,050 | 305 | 43.4 | 566 | 55.2 | 0.86 | 40.8 | 17.4 | 217.7 | 258.5 (*) | 6.7 | 24.2 | 200 |

| 2013 RF98 | Unstable | 6,900 | 370 | 36.1 | 705 | 37.6 | 0.90 | 311.6 | 29.6 | 67.6 | 19.2 | 8.7 | 24.6 | 70 |

| 2013 RA109 | ? | 9,950 | 463 | 46.0 | 880 | 47.4 | 0.90 | 262.9 | 12.4 | 104.8 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 23.1 | 200 |

| 2013 SY99 | Metastable | 19,800 | 733 | 50.0 | 1,420 | 57.9 | 0.93 | 32.2 | 4.2 | 29.5 | 61.7 | 6.7 | 24.5 | 250 |

| 2013 SL102 | Unstable | 5,590 | 326 | 38.1 | 614 | 39.3 | 0.88 | 265.4 | 6.5 | 94.6 | 0.0 (*) | 7.0 | 23.2 | 140 |

| 2014 FE72 | Unstable | 92,400 | 2,040 | 36.1 | 4,050 | 64.0 | 0.98 | 133.9 | 20.6 | 336.8 | 110.7 | 6.2 | 24.3 | 200 |

| 2014 SX403 | ? | 7,180 | 370 | 35.5 | 710 | 45.1 | 0.90 | 174.7 | 42.9 | 149.2 | 323.9 (*) | 7.1 | 23.8 | 130 |

| 2014 SR349 | Stable | 5,160 | 312 | 47.7 | 576 | 54.8 | 0.85 | 340.8 | 18.0 | 34.9 | 15.6 | 6.7 | 24.2 | 200 |

| 2014 TU115 | ? | 6,140 | 335 | 35.0 | 636 | 35.3 | 0.90 | 225.3 | 23.5 | 192.3 | 57.7 | 7.9 | 23.5 | 90 |

| 2014 WB556 | Metastable? | 4,900 | 288 | 42.7 | 534 | 46.6 | 0.85 | 235.3 | 24.2 | 114.7 | 350.0 (*) | 7.3 | 24.2 | 150 |

| 2015 BP519[29] | ? | 9,500 | 433 | 35.2 | 831 | 51.4 | 0.92 | 348.2 | 54.1 | 135.0 | 123.3 (*) | 4.5 | 21.7 | 550[30] |

| 2015 DY248 | ? | 5,400 | 309 | 34.0 | 585 | 34.4 | 0.89 | 244.6 | 12.9 | 273.1 | 157.7 (*) | 8.3 | 23.9 | 100 |

| 2015 DM319 (uo5m93)[31] |

Unstable? | 4,620 | 278 | 39.5 | 516 | 41.7 | 0.86 | 43.4 | 6.8 | 166.0 | 209.4 (*) | 8.7 | 25.0 | 80? |

| 2015 GT50 | Unstable | 5,510 | 314 | 38.5 | 589 | 42.9 | 0.88 | 129.3 | 8.8 | 46.1 | 175.4 (*) | 8.5 | 24.9 | 80 |

| 2015 KG163 | Unstable | 22,840 | 805 | 40.5 | 1,570 | 40.5 | 0.95 | 32.3 | 14.0 | 219.1 | 251.4 (*) | 8.2 | 24.4 | 100 |

| 2015 RX245 | Metastable | 8,920 | 421 | 45.7 | 796 | 59.9 | 0.89 | 64.8 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 73.4 | 6.2 | 24.1 | 250 |

| 2016 SA59 | ? | 3,830 | 250 | 39.1 | 451 | 42.3 | 0.84 | 200.3 | 21.5 | 174.7 | 15.0 | 7.8 | 24.2 | 90 |

| 2016 SD106 | ? | 6,550 | 350 | 42.7 | 658 | 44.5 | 0.88 | 162.9 | 4.8 | 219.4 | 22.3 | 6.7 | 23.4 | 160 |

| 2017 OF201 | ? | 24,200 | 837 | 44.9 | 1,629 | 88.5 | 0.95 | 337.7 | 16.2 | 328.6 | 306.3 (*) | 3.5 | 23.0 | 800 |

| 2018 VM35 | Stable | 4,500 | 252 | 45.0 | 459 | 54.8 | 0.82 | 302.9 | 8.5 | 192.4 | 135.3 (*) | 7.7 | 25.2 | 140 |

| 2019 EU5 | ? | 42,600 | 1,220 | 46.8 | 2,400 | 81.1 | 0.96 | 109.2 | 18.2 | 109.2 | 218.4 (*) | 6.4 | 25.6 | 180 |

| 2020 MQ53 | ? | 21,395 | 770 | 55.6 | 1,486 | — | 0.93 | 18.6 | 73.4 | 287.1 | 305.7 (*) | 8.6 | 70 | |

| 2021 DK18 | ? | 21,400 | 770 | 44.4 | 1,500 | 66.3 | 0.94 | 234.8 | 15.4 | 322.3 | 197.0 (*) | 6.8 | 25.1 | 180 |

| 2021 RR205 | ? | 31,200 | 992 | 55.5 | 1,930 | 60.0 | 0.94 | 208.6 | 7.6 | 108.3 | 316.9 (*) | 6.8 | 24.6 | 180 |

| Ideal elements under hypothesis |

— | >250 | >30 | — | — | >0.5 | — | 10~30 | — | 2~120 | — | — | — | |

| Hypothesized Planet Nine |

15000 8,000–22,000 | 600 400–800 | 200 ~200 | 1000 ~1,000 | 1000 ~1,000? | 0.6 0.2–0.5 | 150 ~150 | 20 15–25 | 91 91±15 | 241 241±15 | 22.5 >22.5 | 40000 ~40,000

| ||

- (*) longitude of perihelion, ϖ, outside expected range;

- are the objects included in the original study by Trujillo and Sheppard (2014).[32]

- has been added in the 2016 study by Brown and Batygin.[18][33][34]

- All other objects have been announced later.

The most extreme case is that of 2015 BP519, nicknamed Caju, which has both the highest inclination[35] and the farthest nodal distance; these properties make it a probable outlier within this population.[2]

Notes

- ↑ The three sednoids (pink) along with the red-colored extreme trans-Neptunian object (ETNO) orbits are suspected to be aligned with the hypothetical Planet Nine while the blue-colored ETNO orbits are anti-aligned. The highly elongated orbits colored brown include centaurs and damocloids with large aphelion distances over 200 AU.

- ↑ Given the orbital eccentricity of these objects, different epochs can generate quite different heliocentric unperturbed two-body best-fit solutions to the semi-major axis and orbital period. For objects at such high eccentricity, the Sun's barycenter is more stable than heliocentric values. Barycentric values better account for the changing position of Jupiter over Jupiter's 12 year orbit. As an example, 2007 TG422 has an epoch 2012 heliocentric period of ~13,500 years,[26] yet an epoch 2020 heliocentric period of ~10,800 years.[27] The barycentric solution is a much more stable ~11,300 years.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Sheppard, Scott S.; Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Tholen, David J.; Kaib, Nathan (2019). "A New High Perihelion Trans-Plutonian Inner Oort Cloud Object: 2015 TG387". The Astronomical Journal 157 (4): 139. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab0895. Bibcode: 2019AJ....157..139S.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (12 September 2018). "A Fruit of a Different Kind: 2015 BP519 as an Outlier among the Extreme Trans-Neptunian Objects". Research Notes of the AAS 2 (3): 167. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/aadfec. Bibcode: 2018RNAAS...2..167D.

- ↑ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (1 September 2021). "Peculiar orbits and asymmetries in extreme trans-Neptunian space". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 506 (1): 633–649. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab1756. Bibcode: 2021MNRAS.506..633D. https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/506/1/633/6307523.

- ↑ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (1 May 2022). "Twisted extreme trans-Neptunian orbital parameter space: statistically significant asymmetries confirmed". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters 512 (1): L6–L10. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slac012. Bibcode: 2022MNRAS.512L...6D. https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/article-abstract/512/1/L6/6524836.

- ↑ Wall, Mike (24 August 2011). "A Conversation With Pluto's Killer: Q & A With Astronomer Mike Brown". http://www.space.com/12711-pluto-killer-mike-brown-dwarf-planets-interview.html.

- ↑ Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick; Rabinowitz, David (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid". The Astrophysical Journal 617 (1): 645–649. doi:10.1086/422095. Bibcode: 2004ApJ...617..645B.

- ↑ Brown, Michael E. (28 October 2010). "There's something out there – part 2". http://www.mikebrownsplanets.com/2010/10/theres-something-out-there-part-2.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Objects beyond Neptune provide fresh evidence for Planet Nine". 2016-10-25. https://www.science.org/content/article/objects-beyond-neptune-provide-fresh-evidence-planet-nine. "The new evidence leaves astronomer Scott Sheppard of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., "probably 90% sure there's a planet out there." But others say the clues are sparse and unconvincing. "I give it about a 1% chance of turning out to be real," says astronomer JJ Kavelaars, of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory in Victoria, Canada."

- ↑ "PLANET 9 SEARCH TURNING UP WEALTH OF NEW OBJECTS". 2016-08-30. http://www.universetoday.com/130524/planet-9-search-turning-wealth-new-objects/.

- ↑ "Extreme New Objects Found At The Edge of The Solar System". 30 August 2016. http://www.iflscience.com/space/extreme-new-objects-found-at-the-edge-of-the-solar-system/.

- ↑ "The Search for Planet Nine: New Finds Boost Case for Distant World". 29 August 2016. http://www.space.com/33890-planet-nine-existence-evidence-grows.html.

- ↑ "HUNT FOR NINTH PLANET REVEALS NEW EXTREMELY DISTANT SOLAR SYSTEM OBJECTS". 2016-08-29. https://carnegiescience.edu/news/hunt-ninth-planet-reveals-new-extremely-distant-solar-system-objects.

- ↑ Shankman, Cory (2017). "OSSOS VI. Striking Biases in the detection of large semimajor axis Trans-Neptunian Objects". The Astronomical Journal 154 (4): 50. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa7aed. Bibcode: 2017AJ....154...50S. https://pure.qub.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/ossos-vi-striking-biases-in-the-detection-of-large-semimajor-axis-transneptunian-objects(027b7a9c-a171-42b4-9449-9355b0a255d4).html.

- ↑ SETI Institute (18 March 2016). "Exploring the outer Solar System: now in vivid colour – Michele Bannister (SETI Talks)". YouTube. 28:17. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_w9N6yABAW4&t=28m17s.

- ↑ Bannister, Michele T. (2016). "A new high-perihelion a ~700 AU object in the distant Solar System". American Astronomical Society, DPS Meeting #48, Id. 113.08 48: 113.08. Bibcode: 2016DPS....4811308B.

- ↑ Hand, Eric (20 January 2016). "Astronomers say a Neptune-sized planet lurks beyond Pluto". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aae0237. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/01/feature-astronomers-say-neptune-sized-planet-lurks-unseen-solar-system. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Grush, Loren (20 January 2016). "Our solar system may have a ninth planet after all — but not all evidence is in (We still haven't seen it yet)". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2016/1/20/10801824/ninth-planet-x-discovered-evidence. "The statistics do sound promising, at first. The researchers say there's a 1 in 15,000 chance that the movements of these objects are coincidental and don't indicate a planetary presence at all. ... 'When we usually consider something as clinched and air tight, it usually has odds with a much lower probability of failure than what they have,' says Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT. For a study to be a slam dunk, the odds of failure are usually 1 in 1,744,278 . ... But researchers often publish before they get the slam-dunk odds, in order to avoid getting scooped by a competing team, Seager says. Most outside experts agree that the researchers' models are strong. And Neptune was originally detected in a similar fashion — by researching observed anomalies in the movement of Uranus. Additionally, the idea of a large planet at such a distance from the Sun isn't actually that unlikely, according to Bruce Macintosh, a planetary scientist at Stanford University."

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E. (2016). "Evidence for a distant giant planet in the Solar system". The Astronomical Journal 151 (2): 22. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/2/22. Bibcode: 2016AJ....151...22B.

- ↑ Koponyás, Barbara (10 April 2010). "Near-Earth asteroids and the Kozai mechanism". http://www.univie.ac.at/adg/Conferences/ahw5/talks/KoponysBarbara.pdf.pdf.

- ↑ Rice, Malena; Laughlin, Gregory (December 2020). "Exploring Trans-Neptunian Space with TESS: A Targeted Shift-stacking Search for Planet Nine and Distant TNOs in the Galactic Plane". The Planetary Science Journal 1 (3): 81 (18 pp.). doi:10.3847/PSJ/abc42c. Bibcode: 2020PSJ.....1...81R.

- ↑ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl; Vaduvescu, Ovidiu; Stanescu, Malin (June 2022). "Distant trans-Neptunian object candidates from NASA's TESS mission scrutinized: fainter than predicted or false positives?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters 513 (1): L78–L82. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slac036. Bibcode: 2022MNRAS.513L..78D. https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/article-abstract/513/1/L78/6565292.

- ↑ "Distant Trans-Neptunian Object Candidates: Fainter Than Predicted or False Positives?". 20 May 2022. https://www.ing.iac.es/PR/press/tess.html.

- ↑ Horizons output. "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements". http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/horizons.cgi?find_body=1&body_group=sb&sstr=. (Solution using the Solar System Barycenter and barycentric coordinates. (Type the target body's name, then select Ephemeris Type:Elements and Center:@0) In the second pane "PR=" can be found, which gives the orbital period in days (For Sedna as an example, the value 4.16E+06 is displayed, which is ~11400 Julian years).

- ↑ "MPC list of q > 30 and a > 250". Minor Planet Center. http://minorplanetcenter.net/db_search/show_by_properties?perihelion_distance_min=30&semimajor_axis_min=250.

- ↑ Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E. (2021). "Injection of Inner Oort Cloud Objects into the Distant Kuiper Belt by Planet Nine". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 910 (2): L20. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/abee1f. Bibcode: 2021ApJ...910L..20B.

- ↑ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". 13 December 2012. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2007TG422.

- ↑ Chamberlin, Alan. "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2007TG422.

- ↑ Relative to hypothetical Planet Nine, Batygin, Konstantin; Adams, Fred C.; Brown, Michael E.; Becker, Juliette C. (2019). "The planet nine hypothesis". Physics Reports 805: 1–53. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2019.01.009. Bibcode: 2019PhR...805....1B.

- ↑ Becker, Juliette (2017). "Evaluating the Dynamical Stability of Outer Solar System Objects in the Presence of Planet Nine". DPS49. American Astronomical Society. https://aas.org/files/resources/dps49_becker.pptx. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Lovett, Richard A. (16 December 2017). "The hidden hand – Could a bizarre hidden planet be manipulating the solar system". New Scientist International (3156): 41. https://www.newscientist.com/issue/3156. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Bannister, Michelle T. (2018). "OSSOS. VII. 800+ Trans-Neptunian Objects — The complete data release". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 236 (1): 18. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/aab77a. Bibcode: 2018ApJS..236...18B.

- ↑ Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units". Nature 507 (7493): 471–474. doi:10.1038/nature13156. PMID 24670765. Bibcode: 2014Natur.507..471T. http://home.dtm.ciw.edu/users/sheppard/pub/TrujilloSheppard2014.pdf. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- ↑ "Where is Planet Nine?". 20 January 2016. http://www.findplanetnine.com/p/blog-page.html.

- ↑ Witze, Alexandra (2016). "Evidence grows for giant planet on fringes of Solar System". Nature 529 (7586): 266–7. doi:10.1038/529266a. PMID 26791699. Bibcode: 2016Natur.529..266W.

- ↑ Becker, J. C. (2018). "Discovery and Dynamical Analysis of an Extreme Trans-Neptunian Object with a High Orbital Inclination". The Astronomical Journal 156 (2): 81. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aad042. Bibcode: 2018AJ....156...81B.

External links

- Known extreme outer solar system objects, Scott Sheppard, Carnegie Science Center

- Hunt for Ninth Planet Reveals New Extremely Distant Solar System Objects, Scott Sheppard, Carnegie Science Center

- List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects (including ESDOs and EDDOs), Robert Johnston, Johnston's Archive

Template:Extreme trans-Neptunian objects

|