Medicine:Phenylketonuria

| Phenylketonuria | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency, PAH deficiency, Følling disease[1] |

| |

| Phenylalanine | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, pediatrics, dietetics |

| Symptoms | Without treatment intellectual disability, seizures, behavioral problems, mental disorders, musty odor[1] |

| Usual onset | At birth[2] |

| Types | Classic, variant[1] |

| Causes | Genetic (autosomal recessive)[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Newborn screening programs in many countries[3] |

| Treatment | Diet low in foods that contain phenylalanine; special supplements[2] |

| Medication | Sapropterin dihydrochloride,[2] pegvaliase[4] |

| Prognosis | Normal health with treatment[5] |

| Frequency | ~1 in 12,000 newborns[6] |

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is an inborn error of metabolism that results in decreased metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine.[3] Untreated PKU can lead to intellectual disability, seizures, behavioral problems, and mental disorders.[1][7] It may also result in a musty smell and lighter skin.[1] A baby born to a mother who has poorly treated PKU may have heart problems, a small head, and low birth weight.[1]

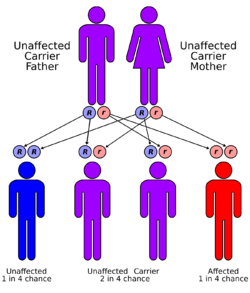

Phenylketonuria is an inherited genetic disorder.[1] It is caused by mutations in the PAH gene, which can result in inefficient or nonfunctional phenylalanine hydroxylase, an enzyme responsible for the metabolism of excess phenylalanine.[1] This results in the buildup of dietary phenylalanine to potentially toxic levels.[1] It is autosomal recessive, meaning that both copies of the gene must be mutated for the condition to develop.[1] There are two main types, classic PKU and variant PKU, depending on whether any enzyme function remains.[1] Those with one copy of a mutated gene typically do not have symptoms.[1] Many countries have newborn screening programs for the disease.[3]

Treatment is with a diet that (1) is low in foods that contain phenylalanine, and which (2) includes special supplements.[2] Babies should use a special formula with a small amount of breast milk.[2] The diet should begin as soon as possible after birth and be continued for life.[2] People who are diagnosed early and maintain a strict diet can have normal health and a normal life span.[5] Effectiveness is monitored through periodic blood tests.[5] The medication sapropterin dihydrochloride may be useful in some.[2]

Phenylketonuria affects about 1 in 12,000 babies.[6] Males and females are affected equally.[8] The disease was discovered in 1934 by Ivar Asbjørn Følling, with the importance of diet determined in 1935.[9] As of 2023, genetic therapies that aim to directly restore liver PAH activity are a promising and active research field.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Untreated PKU can lead to intellectual disability, seizures, behavioral problems, and mental disorders.[1] It may also result in a musty smell and lighter skin.[1] A baby born to a mother who has poorly treated PKU may have heart problems, a small head, and low birth weight.[1]

Because the mother's body is able to break down phenylalanine during pregnancy, infants with PKU are normal at birth. The disease is not detectable by physical examination at that time, because no damage has yet been done. Newborn screening is performed to detect the disease and initiate treatment before any damage is done. The blood sample is usually taken by a heel prick, typically performed 2–7 days after birth. This test can reveal elevated phenylalanine levels after one or two days of normal infant feeding.[11][12]

If a child is not diagnosed during the routine newborn screening test and a phenylalanine-restricted diet is not introduced, then phenylalanine levels in the blood will increase over time. Toxic levels of phenylalanine (and insufficient levels of tyrosine) can interfere with infant development in ways that have permanent effects. The disease may present clinically with seizures, hypopigmentation (excessively fair hair and skin), and a "musty odor" to the baby's sweat and urine (due to phenylacetate, a carboxylic acid produced by the oxidation of phenylacetone). In most cases, a repeat test should be done at approximately two weeks of age to verify the initial test and uncover any phenylketonuria that was initially missed.[13]

Untreated children often fail to attain early developmental milestones, develop microcephaly, and demonstrate progressive impairment of cerebral function. Hyperactivity, EEG abnormalities, and seizures, and severe learning disabilities are major clinical problems later in life. A characteristic "musty or mousy" odor on the skin, as well as a predisposition for eczema, persist throughout life in the absence of treatment.[14]

The damage done to the brain if PKU is untreated during the first months of life is not reversible. It is critical to control the diet of infants with PKU very carefully so that the brain has an opportunity to develop normally. Affected children who are detected at birth and treated are much less likely to develop neurological problems or have seizures and intellectual disability (though such clinical disorders are still possible including asthma, eczema, anemia, weight gain, renal insufficiency, osteoporosis, gastritis, esophagus, and kidney deficiencies, kidney stones, and hypertension). Additionally, major depressive disorders occur 230% higher than controls; dizziness and giddiness occur 180% higher; chronic ischemic heart disease, asthma, diabetes, and gastroenteritis occur 170% higher; and stress and adjustment disorders occur 160% higher.[15][16] In general, however, outcomes for people treated for PKU are good. Treated people may have no detectable physical, neurological, or developmental problems at all.

Genetics

PKU is an autosomal recessive metabolic genetic disorder. As an autosomal recessive disorder, two PKU alleles are required for an individual to experience symptoms of the disease. For a child to inherit PKU, both the mother and father must have and pass on the defective gene.[17] If both parents are carriers for PKU, there is a 25% chance any child they have will be born with the disorder, a 50% chance the child will be a carrier and a 25% chance the child will neither develop nor be a carrier for the disease.[5]

PKU is characterized by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the gene for the hepatic enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), rendering it nonfunctional.[18]:541 This enzyme is necessary to metabolize the amino acid phenylalanine (Phe) to the amino acid tyrosine (Tyr). When PAH activity is reduced, phenylalanine accumulates and is converted into phenylpyruvate (also known as phenylketone), which can be detected in the urine.[19]

Carriers of a single PKU allele do not exhibit symptoms of the disease but appear to be protected to some extent against the fungal toxin ochratoxin A.[20] Louis Woolf suggested that this accounted for the persistence of the allele in certain populations,[20] in that it confers a selective advantage—in other words, being a heterozygote is advantageous.[21]

The PAH gene is located on chromosome 12 in the bands 12q22-q24.2.[22] As of 2000, around 400 disease-causing mutations had been found in the PAH gene. This is an example of allelic genetic heterogeneity.[5]

Pathophysiology

When phenylalanine (Phe) cannot be metabolized by the body, a typical diet that would be healthy for people without PKU causes abnormally high levels of Phe to accumulate in the blood, which is toxic to the brain. If left untreated (and often even in treatment), complications of PKU include severe intellectual disability, brain function abnormalities, microcephaly, mood disorders, irregular motor functioning, and behavioral problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, as well as physical symptoms such as a "musty" odor, eczema, and unusually light skin and hair coloration.[23]

Classical PKU

Classical PKU, and its less severe forms "mild PKU" and "mild hyperphenylalaninemia" are caused by a mutated gene for the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), which converts the amino acid phenylalanine ("Phe") to other essential compounds in the body, in particular tyrosine. Tyrosine is a conditionally essential amino acid for PKU patients because without PAH it cannot be produced in the body through the breakdown of phenylalanine.

PAH deficiency causes a spectrum of disorders, including classic phenylketonuria (PKU) and mild hyperphenylalaninemia (also known as "hyperphe" or "mild HPA"),[24] a less severe accumulation of phenylalanine. Compared to classic PKU patients, patients with "hyperphe" have greater PAH enzyme activity and are able to tolerate larger amounts of phenylalanine in their diets. Without dietary intervention, mild HPA patients have blood Phe levels higher than those with normal PAH activity. There is currently no international consensus on the definition of mild HPA, however, it is most frequently diagnosed at blood Phe levels between 2–6 mg/dL.[25]

Phenylalanine is a large, neutral amino acid (LNAA). LNAAs compete for transport across the blood–brain barrier (BBB) via the large neutral amino acid transporter (LNAAT). If phenylalanine is in excess in the blood, it will saturate the transporter. Excessive levels of phenylalanine tend to decrease the levels of other LNAAs in the brain. As these amino acids are necessary for protein and neurotransmitter synthesis, Phe buildup hinders the development of the brain, causing intellectual disability.[26]

Recent research suggests that neurocognitive, psychosocial, quality of life, growth, nutrition, bone pathology are slightly suboptimal even for patients who are treated and maintain their Phe levels in the target range, if their diet is not supplemented with other amino acids.[27]

Classic PKU affects myelination and white matter tracts in untreated infants; this may be one major cause of neurological problems associated with phenylketonuria. Differences in white matter development are observable with magnetic resonance imaging. Abnormalities in gray matter can also be detected,[28] particularly in the motor and pre-motor cortex, thalamus and the hippocampus.[29]

It was recently suggested that PKU may resemble amyloid diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease, due to the formation of toxic amyloid-like assemblies of phenylalanine.[30]

Tetrahydrobiopterin-deficient hyperphenylalaninemia

A rarer form of hyperphenylalaninemia is tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency, which occurs when the PAH enzyme is normal, and a defect is found in the biosynthesis or recycling of the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4).[31] BH4 is necessary for proper activity of the enzyme PAH, and this coenzyme can be supplemented as treatment. Those with this form of hyperphenylalaninemia may have a deficiency of tyrosine (which is created from phenylalanine by PAH), in which case treatment is supplementation of tyrosine to account for this deficiency.[citation needed]

Levels of dopamine can be used to distinguish between these two types. Tetrahydrobiopterin is required to convert Phe to Tyr and is required to convert Tyr to L-DOPA via the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase. L-DOPA, in turn, is converted to dopamine. Low levels of dopamine lead to high levels of prolactin. By contrast, in classical PKU (without dihydrobiopterin involvement), prolactin levels would be relatively normal.[32][citation needed]

As of 2020, tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency was known to result from defects in five genes.[33]

Metabolic pathways

The enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase normally converts the amino acid phenylalanine into the amino acid tyrosine. If this reaction does not take place, phenylalanine accumulates and tyrosine is deficient. Excessive phenylalanine can be metabolized into phenylketones through the minor route, a transaminase pathway with glutamate. Metabolites include phenylacetate, phenylpyruvate and phenethylamine.[34] Elevated levels of phenylalanine in the blood and detection of phenylketones in the urine is diagnostic, however most patients are diagnosed via newborn screening.[citation needed]

Screening

PKU is commonly included in the newborn screening panel of many countries, with varied detection techniques. Most babies in developed countries are screened for PKU soon after birth.[35] Screening for PKU is done with bacterial inhibition assay (Guthrie test), immunoassays using fluorometric or photometric detection, or amino acid measurement using tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Measurements done using MS/MS determine the concentration of Phe and the ratio of Phe to tyrosine, the ratio will be elevated in PKU.[36]

Treatment

PKU is not curable. However, if PKU is diagnosed early enough, an affected newborn can grow up with normal brain development by managing and controlling phenylalanine ("Phe") levels through diet, or a combination of diet and medication.[37]

Diet

People who follow the prescribed dietary treatment from birth may (but not always) have no symptoms. Their PKU would be detectable only by a blood test. People must adhere to a special diet low in Phe for optimal brain development. Since Phe is necessary for the synthesis of many proteins, it is required for appropriate growth, but levels must be strictly controlled.

Optimal health ranges (or "target ranges") are between 120 and 360 μmol/L or equivalently 2 to 6 mg/dL. This is optimally to be achieved during at least the first 10 years,[38] to allow the brain to develop normally.

The diet requires restricting or eliminating foods high in Phe, such as soybeans, egg whites, shrimp, chicken breast, spirulina, watercress, fish, nuts, crayfish, lobster, tuna, turkey, legumes, and lowfat cottage cheese.[39] Starchy foods, such as potatoes and corn are generally acceptable in controlled amounts, but the quantity of Phe consumed from these foods must be monitored. A corn-free diet may be prescribed in some cases. A food diary is usually kept to record the amount of Phe consumed with each meal, snack, or drink. An "exchange" system can be used to calculate the amount of Phe in a portion of food from the protein content identified on a nutritional information label. Lower-protein "medical food" substitutes are often used in place of normal bread, pasta, and other grain-based foods, which contain a significant amount of Phe. Many fruits and vegetables are lower in Phe and can be eaten in larger quantities. Infants may still be breastfed to provide all of the benefits of breastmilk, but the quantity must also be monitored and supplementation for missing nutrients will be required. The sweetener aspartame, present in many diet foods and soft drinks, must also be avoided, as aspartame contains phenylalanine.[40]

Different people can tolerate different amounts of Phe in their diet. Regular blood tests are used to determine the effects of dietary Phe intake on blood Phe level.

Nutritional supplements

Supplementary "protein substitute" formulas are typically prescribed for people PKU (starting in infancy) to provide the amino acids and other necessary nutrients that would otherwise be lacking in a low-phenylalanine diet. Tyrosine, which is normally derived from phenylalanine and which is necessary for normal brain function, is usually supplemented. Consumption of the protein substitute formulas can actually reduce phenylalanine levels, probably because it stops the process of protein catabolism from releasing Phe stored in the muscles and other tissues into the blood. Many PKU patients have their highest Phe levels after a period of fasting (such as overnight) because fasting triggers catabolism.[41] A diet that is low in phenylalanine but does not include protein substitutes may also fail to lower blood Phe levels, since a nutritionally insufficient diet may also trigger catabolism. For all these reasons, the prescription formula is an important part of the treatment for patients with classic PKU.[citation needed]

Evidence supports dietary supplementation with large neutral amino acids (LNAAs).[42] The LNAAs (e.g. leu, tyr, trp, met, his, ile, val, thr) may compete with phe for specific carrier proteins that transport LNAAs across the intestinal mucosa into the blood and across the blood–brain barrier into the brain. Its use is limited in the US due to the cost but is available in most countries as part of a low protein / PHE diet to replace missing nutrients.

Another interesting treatment strategy is casein glycomacropeptide (CGMP), which is a milk peptide naturally free of Phe in its pure form[43] CGMP can substitute for the main part of the free amino acids in the PKU diet and provides several beneficial nutritional effects compared to free amino acids. The fact that CGMP is a peptide ensures that the absorption rate of its amino acids is prolonged compared to free amino acids and thereby results in improved protein retention[44] and increased satiety[45] compared to free amino acids. Another important benefit of CGMP is that the taste is significantly improved[44] when CGMP substitutes part of the free amino acids and this may help ensure improved compliance to the PKU diet.

Furthermore, CGMP contains a high amount of the Phe-lowering LNAAs, which constitutes about 41 g per 100 g protein[43] and will therefore help maintain plasma phe levels in the target range.

Enzyme substitutes

In 2018, the FDA approved an enzyme substitute called pegvaliase which metabolizes phenylalanine.[4] It is for adults who are poorly managed on other treatments.[4]

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) (a cofactor for the oxidation of phenylalanine) when taken by mouth can reduce blood levels of this amino acid in some people.[46][47]

Mothers

For women with PKU, it is important for the health of their children to maintain low Phe levels before and during pregnancy.[48] Though the developing fetus may only be a carrier of the PKU gene, the intrauterine environment can have very high levels of phenylalanine, which can cross the placenta. The child may develop congenital heart disease, growth retardation, microcephaly and intellectual disability as a result.[49] PKU-affected women themselves are not at risk of additional complications during pregnancy.[citation needed]

In most countries, women with PKU who wish to have children are advised to lower their blood Phe levels (typically to between 2 and 6 mg/dL) before they become pregnant, and carefully control their levels throughout the pregnancy. This is achieved by performing regular blood tests and adhering very strictly to a diet, in general monitored on a day-to-day basis by a specialist metabolic dietitian. In many cases, as the fetus' liver begins to develop and produce PAH normally, the mother's blood Phe levels will drop, requiring an increased intake to remain within the safe range of 2–6 mg/dL. The mother's daily Phe intake may double or even triple by the end of the pregnancy, as a result. When maternal blood Phe levels fall below 2 mg/dL, anecdotal reports indicate that the mothers may experience adverse effects, including headaches, nausea, hair loss, and general malaise. When low phenylalanine levels are maintained for the duration of pregnancy, there are no elevated levels of risk of birth defects compared with a baby born to a non-PKU mother.[50]

Epidemiology

| Country | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Australia | 1 in 10,000[51] |

| Brazil | 1 in 8,690 |

| Canada | 1 in 22,000[51] |

| China | 1 in 17,000[51] |

| Czechoslovakia | 1 in 7,000[51] |

| Denmark | 1 in 12,000[51] |

| Finland | 1 in 200,000[51] |

| France | 1 in 13,500[51] |

| India | 1 in 18,300 |

| Ireland | 1 in 4,500[52] |

| Italy | 1 in 17,000[51] |

| Japan | 1 in 125,000[51] |

| South Korea | 1 in 41,000[53] |

| Netherlands | 1 in 18,000[54] |

| Norway | 1 in 14,500[51] |

| Philippines | 1 in 102,000[55] |

| Poland | 1 in 8,000[54] |

| Scotland | 1 in 5,300[51] |

| Spain | 1 in 20,000[54] |

| Sweden | 1 in 20,000[54] |

| Turkey | 1 in 2,600[51] |

| United Kingdom | 1 in 10,000[54] |

| United States | 1 in 25,000[56] |

The average number of new cases of PKU varies in different human populations. United States Caucasians are affected at a rate of 1 in 10,000.[57] Turkey has the highest documented rate in the world, with 1 in 2,600 births, while countries such as Finland and Japan have extremely low rates with fewer than one case of PKU in 100,000 births. A 1987 study from Slovakia reports a Roma population with an extremely high incidence of PKU (one case in 40 births) due to extensive inbreeding.[58] It is the most common amino acid metabolic problem in the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

History

Before the causes of PKU were understood, PKU caused severe disability in most people who inherited the relevant mutations. Nobel and Pulitzer Prize winning author Pearl S. Buck had a daughter named Carol who lived with PKU before treatment was available, and wrote an account of its effects in a book called The Child Who Never Grew.[59] Many untreated PKU patients born before widespread newborn screening are still alive, largely in dependent living homes/institutions.[60]

Phenylketonuria was discovered by the Norwegian physician Ivar Asbjørn Følling in 1934[61] when he noticed hyperphenylalaninemia (HPA) was associated with intellectual disability. In Norway, this disorder is known as Følling's disease, named after its discoverer.[62] Følling was one of the first physicians to apply detailed chemical analysis to the study of disease.

In 1934 at Rikshospitalet, Følling saw a young woman named Borgny Egeland. She had two children, Liv and Dag, who had been normal at birth but subsequently developed intellectual disability. When Dag was about a year old, the mother noticed a strong smell to his urine. Følling obtained urine samples from the children and, after many tests, he found that the substance causing the odor in the urine was phenylpyruvic acid. The children, he concluded, had excess phenylpyruvic acid in the urine, the condition which came to be called phenylketonuria (PKU).[19]

His careful analysis of the urine of the two affected siblings led him to request many physicians near Oslo to test the urine of other affected patients. This led to the discovery of the same substance he had found in eight other patients. He conducted tests and found reactions that gave rise to benzaldehyde and benzoic acid, which led him to conclude that the compound contained a benzene ring. Further testing showed the melting point to be the same as phenylpyruvic acid, which indicated that the substance was in the urine.[63]

In 1954, Horst Bickel, Evelyn Hickmans and John Gerrard published a paper that described how they created a diet that was low in phenylalanine and the patient recovered.[64] Bickel, Gerrard and Hickmans were awarded the John Scott Medal in 1962 for their discovery.[64]

PKU was the first disorder to be routinely diagnosed through widespread newborn screening. Robert Guthrie introduced the newborn screening test for PKU in the early 1960s.[65] With the knowledge that PKU could be detected before symptoms were evident, and treatment initiated, screening was quickly adopted around the world. Ireland was the first country to introduce a national screening programme in February 1966,[66] Austria also started screening in 1966[67] and England in 1968.[68]

In 2017 the European Guidelines were published.[69] They were called for by the patient organizations such as the European Society for Phenylketonuria and Allied Disorders Treated as Phenylketonuria.[70][71] They have received some critical reception.[72]

Etymology and pronunciation

The word phenylketonuria uses combining forms of phenyl + ketone + -uria; it is pronounced /ˌfiːnaɪlˌkiːtəˈnjʊəriə, ˌfɛn-, -nɪl-, -nəl-, -toʊ-/[73][74].

Research

Other therapies are under investigation, including gene therapy.

BioMarin is conducting clinical trials to investigate PEG-PAL (PEGylated recombinant phenylalanine ammonia lyase or 'PAL') is an enzyme substitution therapy in which the missing PAH enzyme is replaced with an analogous enzyme that also breaks down Phe. PEG-PAL was in Phase 2 clinical development as of 2015,[75] but was put on clinical hold in September 2021. In February 2022, the FDA issued a statement requiring further data from non-clinical studies to assess oncogenic risk resulting from PEG-PAL treatments.[76]

See also

- Hyperphenylalanemia

- Lofenalac

- Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency

- Flowers for Algernon, which features a character who has phenylketonuria

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 "phenylketonuria". September 8, 2016. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/phenylketonuria.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "What are common treatments for phenylketonuria (PKU)?". 2013-08-23. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/pku/conditioninfo/Pages/treatments.aspx.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Phenylketonuria: a review of current and future treatments". Translational Pediatrics 4 (4): 304–17. October 2015. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.10.07. PMID 26835392.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Press Announcements - FDA approves a new treatment for PKU, a rare and serious genetic disease" (in en). https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm608835.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement Phenylketonuria: Screening and Management". October 16–18, 2000. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/pubs/pku/pages/sub3.aspx.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bernstein, Laurie E.; Rohr, Fran; Helm, Joanna R. (2015). Nutrition Management of Inherited Metabolic Diseases: Lessons from Metabolic University. Springer. p. 91. ISBN 9783319146218. https://books.google.com/books?id=q1LMCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA91.

- ↑ "ADHD symptoms in neurometabolic diseases: Underlying mechanisms and clinical implications". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 132: 838–856. November 2021. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.012. PMID 34774900.

- ↑ Marcdante, Karen; Kliegman, Robert M. (2014). Nelson Essentials of Pediatrics (7 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 150. ISBN 9780323226981. https://books.google.com/books?id=hsY0AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA150.

- ↑ Kalter, Harold (2010). Teratology in the Twentieth Century Plus Ten. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 89–92. ISBN 9789048188208. https://books.google.com/books?id=DykKlVU0V-oC&pg=PA89.

- ↑ Martinez, Michael; Harding, Cary O.; Schwank, Gerald; Thöny, Beat (January 2024). "State-of-the-art 2023 on gene therapy for phenylketonuria" (in en). Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 47 (1): 80–92. doi:10.1002/jimd.12651. ISSN 0141-8955. PMID 37401651.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria (PKU) Test". https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/medical-tests/hw41965.

- ↑ "Newborn screening 50 years later: access issues faced by adults with PKU". Genetics in Medicine 15 (8): 591–9. August 2013. doi:10.1038/gim.2013.10. PMID 23470838.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria (PKU)". Madriella Network. 14 October 2016. https://madriella.org/encyclopedia/phenylketonuria-pku/.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria". Wishart Research Group. https://markerdb.ca/conditions/267.

- ↑ Burton BK, Jones KB, Cederbaum S, Rohr F, Waisbren S, Irwin DE (2018). "Prevalence of comorbid conditions among adult patients diagnosed with phenylketonuria.". Mol Genet Metab 125 (3): 228–234. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.09.006. PMID 30266197.

- ↑ Trefz KF, Muntau AC, Kohlscheen KM, Altevers J, Jacob C, Braun S (2019). "Clinical burden of illness in patients with phenylketonuria (PKU) and associated comorbidities - a retrospective study of German health insurance claims data.". Orphanet J Rare Dis 14 (1): 181. doi:10.1186/s13023-019-1153-y. PMID 31331350.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria (PKU) - Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/phenylketonuria/symptoms-causes/syc-20376302.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gonzalez, Jason; Willis, Monte S. (Feb 2010). "Ivar Asbjörn Følling". Laboratory Medicine 41 (2): 118–119. doi:10.1309/LM62LVV5OSLUJOQF.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "The heterozygote advantage in phenylketonuria". American Journal of Human Genetics 38 (5): 773–5. May 1986. PMID 3717163.

- ↑ Lewis, Ricki (1997). Human Genetics. Chicago, IL: Wm. C. Brown. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-0-697-24030-9.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Roger N.; Barchi, Robert L.; DiMauro, Salvatore; Prusiner, Stanley B.; Nestler, Eric J. (2003) (in en). The Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease. Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 820. ISBN 9780750673600. https://books.google.com/books?id=p3i0BdSlpukC&pg=PA820.

- ↑ Ashe, Killian; Kelso, Wendy; Farrand, Sarah; Panetta, Julie; Fazio, Tim; De Jong, Gerard; Walterfang, Mark (2019). "Psychiatric and Cognitive Aspects of Phenylketonuria: The Limitations of Diet and Promise of New Treatments". Front. Psychiatry 10 (561): 561. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00561. PMID 31551819.

- ↑ Regier, Debra S.; Greene, Carol L. (July 25, 1993). "Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Deficiency". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1504/.

- ↑ "Cognitive functioning in mild hyperphenylalaninemia". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports 5: 72–75. December 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ymgmr.2015.10.009. PMID 28649547.

- ↑ "Large neutral amino acids block phenylalanine transport into brain tissue in patients with phenylketonuria". Journal of Clinical Investigation 103 (8): 1169–1178. 1999. doi:10.1172/JCI5017. PMID 10207169.

- ↑ "Suboptimal outcomes in patients with PKU treated early with diet alone: Revisiting the evidence". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 101 (2–3): 99–109. 1 October 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.05.017. PMID 20678948.

- ↑ "Age-related gray matter volume changes in the brain during non-elderly adulthood". Neurobiology of Aging 32 (2–6): 354–368. 10 May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.008. PMID 19282066.

- ↑ Hawks, Zoë; Hood, Anna M.; Lerman-Sinkoff, Dov B.; Shimony, Joshua S.; Rutlin, Jerrel; Lagoni, Daniel; Grange, Dorothy K.; White, Desirée A. (2019-01-01). "White and gray matter brain development in children and young adults with phenylketonuria". NeuroImage: Clinical 23: 101916. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101916. ISSN 2213-1582. PMID 31491833.

- ↑ "Phenylalanine assembly into toxic fibrils suggests amyloid etiology in phenylketonuria". Nature Chemical Biology 8 (8): 701–6. August 2012. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1002. PMID 22706200.

- ↑ "The neurochemistry of phenylketonuria". European Journal of Pediatrics 169: S109–S113. 2000. doi:10.1007/PL00014370. PMID 11043156.

- ↑ Opladen, Thomas; López-Laso, Eduardo (26 May 2020). "Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 15 (1): 126. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01379-8. PMID 32456656.

- ↑ "Consensus guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) deficiencies". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 15 (1): 126. May 2020. doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01379-8. PMID 32456656.

- ↑ "Phenylalanine metabolites, attention span and hyperactivity". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 42 (2): 361–5. 1985. doi:10.1093/ajcn/42.2.361. PMID 4025205.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Staff (2007-12-20). "Phenylketonuria (PKU)". Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/phenylketonuria/DS00514/DSECTION=1.

- ↑ Sarafoglou, Kyriakie; Hoffmann, Georg F.; Roth, Karl S., eds. Pediatric Endocrinology and Inborn Errors of Metabolism. New York: McGraw Hill Medical. p. 26.

- ↑ Widaman, Keith F. (2009-02-01). "Phenylketonuria in Children and Mothers: Genes, Environments, Behavior". Current Directions in Psychological Science 18 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01604.x. ISSN 0963-7214. PMID 20126294.

- ↑ Chapter 55, page 255 in:Behrman, Richard E.; Kliegman, Robert; Nelson, Waldo E.; Karen Marcdante; Jenson, Hal B. (2006). Nelson essentials of pediatrics. Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-0159-1.

- ↑ "Foods highest in Phenylalanine". self.com. http://nutritiondata.self.com/foods-000086000000000000000-1.html.

- ↑ "CFR – Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 172: Food additives permitted for direct addition to food for human consumption. Subpart I – Multipurpose Additives; Sec. 172.804 Aspartame". US Food and Drug Administration. 1 April 2018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=172.804.

- ↑ "Does a single plasma phenylalanine predict the quality of control in phenylketonuria?". Archives of Disease in Childhood 78 (2): 122–6. 1998. doi:10.1136/adc.78.2.122. PMID 9579152.

- ↑ "Large neutral amino acids in the treatment of PKU: from theory to practice". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease 33 (6): 671–6. December 2010. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9216-1. PMID 20976625.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Etzel MR (Apr 2004). "Manufacture and use of dairy protein fractions.". The Journal of Nutrition 134 (4): 996S–1002S. doi:10.1093/jn/134.4.996S. PMID 15051860.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "Improved nutritional management of phenylketonuria by using a diet containing glycomacropeptide compared with amino acids.". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 89 (4): 1068–77. Apr 2009. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27280. PMID 19244369.

- ↑ "Breakfast with glycomacropeptide compared with amino acids suppresses plasma ghrelin levels in individuals with phenylketonuria.". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 100 (4): 303–8. August 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.04.003. PMID 20466571.

- ↑ Burton, Barbara K.; Kar, Santwana; Kirkpatrick, Peter (2008). "Sapropterin". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 7 (3): 199–200. doi:10.1038/nrd2540.

- ↑ "Sapropterin dihydrochloride, 6-R-L-erythro-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin, in the treatment of phenylketonuria". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 17 (2): 245–51. February 2008. doi:10.1517/13543784.17.2.245. PMID 18230057.

- ↑ "Maternal phenylketonuria: report from the United Kingdom Registry 1978–97". Archives of Disease in Childhood 90 (2): 143–146. 2005. doi:10.1136/adc.2003.037762. PMID 15665165.

- ↑ "Maternal phenylketonuria collaborative study (MPKUCS) offspring: Facial anomalies, malformations, and early neurological sequelae". American Journal of Medical Genetics 69 (1): 89–95. 1997. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970303)69:1<89::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 9066890.

- ↑ lsuhsc.edu Genetics and Louisiana Families

- ↑ 51.00 51.01 51.02 51.03 51.04 51.05 51.06 51.07 51.08 51.09 51.10 51.11 "Phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism". The Clinical Biochemist. Reviews 29 (1): 31–41. February 2008. PMID 18566668.

- ↑ "Molecular structure and polymorphic map of the human phenylalanine hydroxylase gene". Biochemistry 25 (4): 743–749. 1986. doi:10.1021/bi00352a001. PMID 3008810.

- ↑ "The molecular basis of phenylketonuria in Koreans". Journal of Human Genetics 49 (1): 617–621. 2004. doi:10.1007/s10038-004-0197-5. PMID 15503242.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 "PKU: Closing the Gaps in Care". https://www.espku.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/PKU_report_FINAL_v2_nomarks.pdf.

- ↑ "Philippine Society for Orphan Disorders – Current Registry". psod.org.ph. http://www.psod.org.ph/rare-diseases/current-registry/.

- ↑ Phenylketonuria at eMedicine

- ↑ Bickel, H. et al. (1981). "Neonatal mass screening for metabolic disorders". European Journal of Pediatrics 137 (137): 133–139. doi:10.1007/BF00441305. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00441305.

- ↑ "Slovenskí Cigáni (Rómovia) – populácia s najvyšším koeficientom inbrídingu v Európe.". Bratislavské Lekárske Listy 87 (2): 168–175. 1987.

- ↑ "Nicorandil: differential contribution of K+ channel opening and guanylate cyclase stimulation to its vasorelaxant effects on various endothelin-1-contracted arterial preparations. Comparison to aprikalim (RP 52891) and nitroglycerin". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 259 (2): 526–34. November 1991. PMID 1682478.

- ↑ "NPKUA > Education > About PKU". npkua.org. http://www.npkua.org/Education/AboutPKU.aspx.

- ↑ Følling, Asbjørn (1 January 1934). "Über Ausscheidung von Phenylbrenztraubensäure in den Harn als Stoffwechselanomalie in Verbindung mit Imbezillität.". Hoppe-Seyler's Zeitschrift für Physiologische Chemie 227 (1–4): 169–181. doi:10.1515/bchm2.1934.227.1-4.169.

- ↑ "The discovery of phenylketonuria: the story of a young couple, two affected children, and a scientist". Pediatrics 105 (1 Pt 1): 89–103. 2000. doi:10.1542/peds.105.1.89. PMID 10617710.

- ↑ Williams, RA; Mamotte, CD; Burnett, JR (2008). "Phenylketonuria: an inborn error of phenylalanine metabolism". The Clinical Biochemist Reviews 29 (1): 31–41. PMID 18566668. "Mild oxidation of the purified substance produced a compound which smelled of benzoic acid, leading Følling to postulate that the compound was phenylpyruvic acid.3 There was no change in the melting point upon mixing of the unknown compound with phenylpyruvic acid thus confirming the mystery compound was indeed phenylpyruvic acid.".

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Marelene Rayner-Canham, Geoff Rayner-Canham (2008), "Evelyn Hickmans", Chemistry was Their Life: Pioneer British Women Chemists, 1880–1949 (World Scientific): pp. 198, ISBN 9781908978998

- ↑ "Phenylalanine hydroxylase deficiency". Genetics in Medicine 13 (8): 697–707. 2011. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182141b48. PMID 21555948.

- ↑ Koch, Jean (1997). Robert Guthrie--the PKU story : crusade against mental retardation. Pasadena, Calif.: Hope Pub. House. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0932727913. OCLC 36352725.

- ↑ "The National Austrian Newborn Screening Program – Eight years experience with mass spectrometry. Past, present, and future goals". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 122 (21–22): 607–613. 2010. doi:10.1007/s00508-010-1457-3. PMID 20938748.

- ↑ "The Manchester regional screening programme: A 10-year exercise in patient and family care". British Medical Journal 2 (6191): 635–638. 1979. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6191.635. PMID 497752.

- ↑ "The complete European guidelines on phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment" (in En). Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 12 (1): 162. October 2017. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0685-2. PMID 29025426.

- ↑ "Consensus Paper - E.S.PKU" (in en-GB). E.S.PKU. https://www.espku.org/projects/consensus-paper/.

- ↑ "Requirements for a minimum standard of care for phenylketonuria: the patients' perspective" (in En). Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 8 (1): 191. December 2013. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-191. PMID 24341788.

- ↑ "Issues with European guidelines for phenylketonuria". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology 5 (9): 681–683. September 2017. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30201-2. PMID 28842158.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Phenylketonuria.

- ↑ "Phenylketonuria". Phenylketonuria. Oxford University Press. http://www.lexico.com/definition/Phenylketonuria.

- ↑ "BioMarin : Pipeline : Pipeline Overview : BMN 165 for PKU". bmrn.com. https://www.bmrn.com/pipeline/peg-pal-for-pku.php.

- ↑ "BioMarin Provides Updates on Progress in Gene Therapy Programs" (in en-US). https://investors.biomarin.com/2022-02-17-BioMarin-Provides-Updates-on-Progress-in-Gene-Therapy-Programs.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|