Biology:Tyrosine hydroxylase

Generic protein structure example |

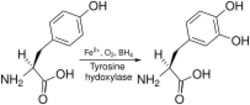

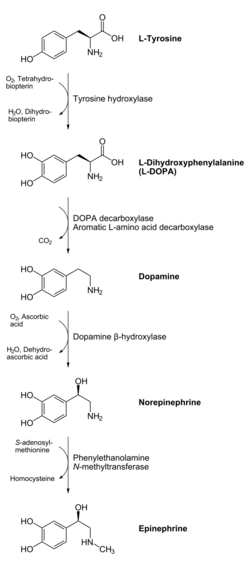

Tyrosine hydroxylase or tyrosine 3-monooxygenase is the enzyme responsible for catalyzing the conversion of the amino acid L-tyrosine to L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA).[1][2] It does so using molecular oxygen (O2), as well as iron (Fe2+) and tetrahydrobiopterin as cofactors. L-DOPA is a precursor for dopamine, which, in turn, is a precursor for the important neurotransmitters norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline). Tyrosine hydroxylase catalyzes the rate limiting step in this synthesis of catecholamines. In humans, tyrosine hydroxylase is encoded by the TH gene,[2] and the enzyme is present in the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral sympathetic neurons and the adrenal medulla.[2] Tyrosine hydroxylase, phenylalanine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase together make up the family of aromatic amino acid hydroxylases (AAAHs).

Reaction

| tyrosine 3-monooxygenase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC number | 1.14.16.2 | ||||||||

| CAS number | 9036-22-0 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Tyrosine hydroxylase catalyzes the reaction in which L-tyrosine is hydroxylated in the meta position to obtain L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA). The enzyme is an oxygenase which means it uses molecular oxygen to hydroxylate its substrates. One of the oxygen atoms in O2 is used to hydroxylate the tyrosine molecule to obtain L-DOPA and the other one is used to hydroxylate the cofactor. Like the other aromatic amino acid hydroxylases (AAAHs), tyrosine hydroxylase use the cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) under normal conditions, although other similar molecules may also work as a cofactor for tyrosine hydroxylase.[3]

The AAAHs converts the cofactor 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) into tetrahydrobiopterin-4a-carbinolamine (4a-BH4). Under physiological conditions, 4a-BH4 is dehydrated to quinonoid-dihydrobiopterin (q-BH2) by the enzyme pterin-4a-carbinolamine dehydrase (PCD) and a water molecule is released in this reaction.[4][5] Then, the NAD(P)H dependent enzyme dihydropteridine reductase (DHPR) converts q-BH2 back to BH4.[4] Each of the four subunits in tyrosine hydroxylase is coordinated with an iron(II) atom presented in the active site. The oxidation state of this iron atom is important for the catalytic turnover in the enzymatic reaction. If the iron is oxidized to Fe(III), the enzyme is inactivated.[6]

The product of the enzymatic reaction, L-DOPA, can be transformed to dopamine by the enzyme DOPA decarboxylase. Dopamine may be converted into norepinephrine by the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase, which can be further modified by the enzyme phenylethanol N-methyltransferase to obtain epinephrine.[7] Since L-DOPA is the precursor for the neurotransmitters dopamine, noradrenaline and adrenaline, tyrosine hydroxylase is therefore found in the cytosol of all cells containing these catecholamines. This initial reaction catalyzed by tyrosine hydroxylase has been shown to be the rate limiting step in the production of catecholamines.[7]

The enzyme is highly specific, not accepting indole derivatives - which is unusual as many other enzymes involved in the production of catecholamines do. Tryptophan is a poor substrate for tyrosine hydroxylase, however it can hydroxylate L-phenylalanine to form L-tyrosine and small amounts of 3-hydroxyphenylalanine.[3][8][9] The enzyme can then further catalyze L-tyrosine to form L-DOPA. Tyrosine hydroxylase may also be involved in other reactions as well, such as oxidizing L-DOPA to form 5-S-cysteinyl-DOPA or other L-DOPA derivatives.[3][10]

Structure

Tyrosine hydroxylase is a tetramer of four identical subunits (homotetramer). Each subunit consists of three domains. At the carboxyl terminal of the peptide chain there's a short alpha helix domain that allows tetramerization.[11] The central ~300 amino acids make up a catalytic core, in which all the residues necessary for catalysis are located, along with a non-covalently bound iron atom.[8] The iron is held in place by two histidine residues and one glutamate residue, making it a non-heme, non-iron-sulfur iron-containing enzyme.[12] The amino terminal ~150 amino acids make up a regulatory domain, thought to control access of substrates to the active site.[13] In humans there are thought to be four different versions of this regulatory domain, and thus four versions of the enzyme, depending on alternative splicing,[14] though none of their structures have yet been properly determined.[15] It has been suggested that this domain might be an intrinsically unstructured protein, which has no clearly defined tertiary structure, but so far no evidence has been presented supporting this claim.[15] It has however been shown that the domain has a low occurrence of secondary structures, which doesn't weaken suspicions of it having a disordered overall structure.[16] As for the tetramerization and catalytic domains their structure was found with rat tyrosine hydroxylase using X-ray crystallography.[17][18] This has shown how its structure is very similar to that of phenylalanine hydroxylase and tryptophan hydroxylase; together the three make up a family of homologous aromatic amino acid hydroxylases.[19][20]

Regulation

Tyrosine hydroxylase activity is increased in the short term by phosphorylation. The regulatory domain of tyrosine hydroxylase contains multiple serine (Ser) residues, including Ser8, Ser19, Ser31 and Ser40, that are phosphorylated by a variety of protein kinases.[8][21] Ser40 is phosphorylated by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase.[22] Ser19 (and Ser40 to a lesser extent) is phosphorylated by the calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase.[23] MAPKAPK2 (mitogen-activated-protein kinase-activating protein kinase) has a preference for Ser40, but also phosphorylates Ser19 about half the rate of Ser40.[24][25] Ser31 is phosphorylated by ERK1 and ERK2 (extracellular regulated kinases 1&2),[26] and increases the enzyme activity to a lesser extent than for Ser40 phosphorylation.[24] The phosphorylation at Ser19 and Ser8 has no direct effect on tyrosine hydroxylase activity. But phosphorylation at Ser19 increases the rate of phosphorylation at Ser40, leading to an increase in enzyme activity. Phosphorylation at Ser19 causes a two-fold increase of activity, through a mechanism that requires the 14-3-3 proteins.[27] Phosphorylation at Ser31 causes a slight increase of activity, and here the mechanism is unknown. Tyrosine hydroxylase is somewhat stabilized to heat inactivation when the regulatory serines are phosphorylated.[24][28]

Tyrosine hydroxylase is mainly present in the cytosol, although it also is found in some extent in the plasma membrane.[29] The membrane association may be related to catecholamine packing in vesicles and export through the synaptic membrane.[29] The binding of tyrosine hydroxylase to membranes involves the N-terminal region of the enzyme, and may be regulated by a three-way interaction between 14-3-3 proteins, the N-terminal region of tyrosine hydroxylase, and negatively charged membranes.[30]

Tyrosine hydroxylase can also be regulated by inhibition. Phosphorylation at Ser40 relieves feedback inhibition by the catecholamines dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine.[31][32] The catecholamines trap the active-site iron in the Fe(III) state, inhibiting the enzyme.[3]

It has been shown that the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase can be affected by the expression of SRY. The down regulation of the SRY gene in the substantia nigra can result in a decrease in tyrosine hydroxylase expression.[33]

Long term regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase can also be mediated by phosphorylation mechanisms. Hormones (e.g. glucocorticoids), drugs (e.g. cocaine), or second messengers such as cAMP increase tyrosine hydroxylase transcription. Increase in tyrosine hydroxylase activity due to phosphorylation can be sustained by nicotine for up to 48 hours.[3][34] Tyrosine hydroxylase activity is regulated chronically (days) by protein synthesis.[34]

Clinical significance

Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency leads to impaired synthesis of dopamine as well as epinephrine and norepinephrine. It is represented by a progressive encephalopathy and poor prognosis. Clinical features include dystonia that is minimally or nonresponsive to levodopa, extrapyramidal symptoms, ptosis, miosis, and postural hypotension. This is a progressive and often lethal disorder, which can be improved but not cured by levodopa.[35] Due to the low number of patients and overlapping symptoms with other disorders, early diagnosis and treatment remain challenging.[36] Response to treatment is variable and the long-term and functional outcome is unknown. To provide a basis for improving the understanding of the epidemiology, genotype/phenotype correlation and outcome of these diseases, their impact on the quality of life of patients, and for evaluating diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, a patient registry was established by the noncommercial International Working Group on Neurotransmitter Related Disorders (iNTD).[37]

Furthermore, alterations in the tyrosine hydroxylase enzyme activity may be involved in disorders such as Segawa's dystonia, Parkinson's disease and schizophrenia.[17][38] Tyrosine hydroxylase is activated by phosphorylation dependent binding to 14-3-3 proteins.[30] Since the 14-3-3 proteins also are likely to be associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease, it makes an indirect link between tyrosine hydroxylase and these diseases.[39] The activity of tyrosine hydroxylase in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease has been shown to be significantly reduced compared to healthy individuals.[40] Tyrosine hydroxylase is also an autoantigen in Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome (APS) type I.[41]

A consistent abnormality in Parkinson's disease is degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to a reduction of striatal dopamine levels. As tyrosine hydroxylase catalyzes the formation of L-DOPA, the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of dopamine, tyrosine hydroxylase-deficiency does not cause Parkinson's disease, but typically gives rise to infantile parkinsonism, although the spectrum extends to a condition resembling dopamine-responsive dystonia. A direct pathogenetic role of tyrosine hydroxylase has also been suggested, as the enzyme is a source of H2O2 and other reactive oxygen species (ROS), and a target for radical-mediated injury. It has been demonstrated that L-DOPA is effectively oxidized by mammalian tyrosine hydroxylase, possibly contributing to the cytotoxic effects of L-DOPA.[3] Like other cellular proteins, tyrosine hydroxylase is also a possible target for damaging alterations induced by ROS. This suggests that some of the oxidative damage to tyrosine hydroxylase could be generated by the tyrosine hydroxylase system itself.[3]

Tyrosine hydroxylase can be inhibited by the drug α-methyl-para-tyrosine (metirosine). This inhibition can lead to a depletion of dopamine and norepinepherine in the brain due to the lack of the precursor L-Dopa (L-3,4-dyhydroxyphenylalanine) which is synthesized by tyrosine hydroxylase. This drug is rarely used and can cause depression, but it is useful in treating pheochromocytoma and also resistant hypertension. Older examples of inhibitors mentioned in the literature include oudenone[42] and aquayamycin.[43]

References

- ↑ "Tyrosine hydroxylase". Advances in Enzymology and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. Advances in Enzymology - and Related Areas of Molecular Biology. 70. 1995. pp. 103–220. doi:10.1002/9780470123164.ch3. ISBN 978-0-470-12316-4.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Tyrosine hydroxylase: human isoforms, structure and regulation in physiology and pathology". Essays in Biochemistry 30: 15–35. 1995. PMID 8822146.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Tyrosine hydroxylase and Parkinson's disease". Molecular Neurobiology 16 (3): 285–309. Jun 1998. doi:10.1007/BF02741387. PMID 9626667.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Selectivity and affinity determinants for ligand binding to the aromatic amino acid hydroxylases". Current Medicinal Chemistry 14 (4): 455–67. 2007. doi:10.2174/092986707779941023. PMID 17305546.

- ↑ "Tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis, regeneration and functions". The Biochemical Journal 347 Pt 1 (1): 1–16. Apr 2000. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3470001. PMID 10727395.

- ↑ "Characterization of the active site iron in tyrosine hydroxylase. Redox states of the iron". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 271 (40): 24395–400. Oct 1996. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.40.24395. PMID 8798695.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Tyrosine Hydroxylase. The Initial Step in Norepinephrine Biosynthesis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 239: 2910–7. Sep 1964. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)93832-9. PMID 14216443.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Tetrahydropterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases". Annual Review of Biochemistry 68: 355–81. 1999. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. PMID 10872454.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick PF (1994). "Kinetic Isotope Effects on Hydroxylation of Ring-Deuterated Phenylalanines by Tyrosine Hydroxylase Provide Evidence against Partitioning of an Arene Oxide Intermediate". Journal of the American Chemical Society 116 (3): 1133–1134. doi:10.1021/ja00082a046.

- ↑ "Isolation and characterization of tetrahydropterin oxidation products generated in the tyrosine 3-monooxygenase (tyrosine hydroxylase) reaction". European Journal of Biochemistry 168 (1): 21–6. Oct 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13381.x. PMID 2889594.

- ↑ "A carboxyl terminal leucine zipper is required for tyrosine hydroxylase tetramer formation". Journal of Neurochemistry 63 (6): 2014–20. Dec 1994. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062014.x. PMID 7964718.

- ↑ "Identification of iron ligands in tyrosine hydroxylase by mutagenesis of conserved histidinyl residues". Protein Science 4 (10): 2082–6. Oct 1995. doi:10.1002/pro.5560041013. PMID 8535244.

- ↑ "Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 508 (1): 1–12. Apr 2011. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2010.12.017. PMID 21176768.

- ↑ "Structure of the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene: alternative splicing from a single gene accounts for generation of four mRNA types". Journal of Biochemistry 103 (6): 907–12. Jun 1988. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122386. PMID 2902075.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Role of N-terminus of tyrosine hydroxylase in the biosynthesis of catecholamines". Journal of Neural Transmission 116 (11): 1355–62. Nov 2009. doi:10.1007/s00702-009-0227-8. PMID 19396395.

- ↑ "The 14-3-3 protein affects the conformation of the regulatory domain of human tyrosine hydroxylase". Biochemistry 47 (6): 1768–77. Feb 2008. doi:10.1021/bi7019468. PMID 18181650.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Crystal structure of tyrosine hydroxylase at 2.3 A and its implications for inherited neurodegenerative diseases". Nature Structural Biology 4 (7): 578–85. Jul 1997. doi:10.1038/nsb0797-578. PMID 9228951.

- ↑ "Crystal structure of tyrosine hydroxylase with bound cofactor analogue and iron at 2.3 A resolution: self-hydroxylation of Phe300 and the pterin-binding site". Biochemistry 37 (39): 13437–45. Sep 1998. doi:10.1021/bi981462g. PMID 9753429.

- ↑ "Homology between phenylalanine and tyrosine hydroxylases reveals common structural and functional domains". Biochemistry 24 (14): 3389–94. Jul 1985. doi:10.1021/bi00335a001. PMID 2412578.

- ↑ "Full-length cDNA for rabbit tryptophan hydroxylase: functional domains and evolution of aromatic amino acid hydroxylases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 84 (16): 5530–4. Aug 1987. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.16.5530. PMID 3475690. Bibcode: 1987PNAS...84.5530G.

- ↑ "Phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in situ at serine 8, 19, 31, and 40". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 265 (20): 11682–91. Jul 1990. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)38451-0. PMID 1973163.

- ↑ "Activation of tyrosine hydroxylase in PC12 cells by the cyclic GMP and cyclic AMP second messenger systems". Journal of Neurochemistry 48 (1): 236–42. Jan 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb13153.x. PMID 2878973.

- ↑ "Differential regulation of the human tyrosine hydroxylase isoforms via hierarchical phosphorylation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 281 (26): 17644–51. Jun 2006. doi:10.1074/jbc.M512194200. PMID 16644734.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "Tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation: regulation and consequences". Journal of Neurochemistry 91 (5): 1025–43. Dec 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02797.x. PMID 15569247.

- ↑ "Phosphorylation and activation of human tyrosine hydroxylase in vitro by mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and MAP-kinase-activated kinases 1 and 2". European Journal of Biochemistry 217 (2): 715–22. Oct 1993. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18297.x. PMID 7901013.

- ↑ "ERK1 and ERK2, two microtubule-associated protein 2 kinases, mediate the phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase at serine-31 in situ". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (6): 2365–9. Mar 1992. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.6.2365. PMID 1347949. Bibcode: 1992PNAS...89.2365H.

- ↑ "Molecular cloning of cDNA coding for brain-specific 14-3-3 protein, a protein kinase-dependent activator of tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 85 (19): 7084–8. Oct 1988. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.19.7084. PMID 2902623. Bibcode: 1988PNAS...85.7084I.

- ↑ "Mutation of regulatory serines of rat tyrosine hydroxylase to glutamate: effects on enzyme stability and activity". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 434 (2): 266–74. Feb 2005. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.007. PMID 15639226.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Demonstration of functional coupling between dopamine synthesis and its packaging into synaptic vesicles". Journal of Biomedical Science 10 (6 Pt 2): 774–81. 2003. doi:10.1159/000073965. PMID 14631117. https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/1808/17671/1/FowlerS_JBS_10%286%29774.pdf.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Three-way interaction between 14-3-3 proteins, the N-terminal region of tyrosine hydroxylase, and negatively charged membranes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 (47): 32758–69. Nov 2009. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.027706. PMID 19801645.

- ↑ "Site-directed mutagenesis of serine 40 of rat tyrosine hydroxylase. Effects of dopamine and cAMP-dependent phosphorylation on enzyme activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 267 (18): 12639–46. Jun 1992. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42325-3. PMID 1352289.

- ↑ "Effects of phosphorylation of serine 40 of tyrosine hydroxylase on binding of catecholamines: evidence for a novel regulatory mechanism". Biochemistry 37 (25): 8980–6. Jun 1998. doi:10.1021/bi980582l. PMID 9636040.

- ↑ "Direct regulation of adult brain function by the male-specific factor SRY". Current Biology 16 (4): 415–20. Feb 2006. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.017. PMID 16488877.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "Sustained phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase at serine 40: a novel mechanism for maintenance of catecholamine synthesis". Journal of Neurochemistry 100 (2): 479–89. Jan 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04213.x. PMID 17064352.

- ↑ "The pediatric neurotransmitter disorders". J Child Neurol 22 (5): 606–616. May 2007. doi:10.1177/0883073807302619. PMID 17690069.

- ↑ "Personalized Medicine to Improve Treatment of Dopa-Responsive Dystonia—A Focus on Tyrosine Hydroxylase Deficiency". J. Pers. Med. 11 (1186): 1186. November 2021. doi:10.3390/jpm11111186. PMID 34834538.

- ↑ "Patient registry". http://intd-online.org/.

- ↑ "Association of DNA polymorphism in the first intron of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene with disturbances of the catecholaminergic system in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research 23 (3): 259–64. Feb 1997. doi:10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00118-1. PMID 9075305.

- ↑ "14-3-3 proteins in neurodegeneration". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 22 (7): 696–704. Sep 2011. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.08.005. PMID 21920445.

- ↑ "Tyrosine hydroxylase, tryptophan hydroxylase, biopterin, and neopterin in the brains of normal controls and patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer type". Journal of Neurochemistry 48 (3): 760–4. Mar 1987. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05582.x. PMID 2879891.

- ↑ "Identification of tyrosine hydroxylase as an autoantigen in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 267 (1): 456–61. Jan 2000. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.1945. PMID 10623641.

- ↑ "Oudenone, a novel tyrosine hydroxylase inhibitor from microbial origin". Journal of the American Chemical Society 93 (5): 1285–6. Mar 1971. doi:10.1021/ja00734a054. PMID 5545929.

- ↑ "Inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase by aquayamycin". The Journal of Antibiotics 21 (5): 350–3. May 1968. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.21.350. PMID 5726288.

Further reading

- "Tyrosine hydroxylase regulation in the central nervous system". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 53-54 (1–2): 129–52. 1983. doi:10.1007/BF00225250. PMID 6137760.

- "Post-genomic era and gene discovery for psychiatric diseases: there is a new art of the trade? The example of the HUMTH01 microsatellite in the Tyrosine Hydroxylase gene". Molecular Neurobiology 26 (2–3): 389–403. 2002. doi:10.1385/MN:26:2-3:389. PMID 12428766.

- "Direct phosphorylation of brain tyrosine hydroxylase by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase: mechanism of enzyme activation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 75 (10): 4744–8. Oct 1978. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.10.4744. PMID 33381. Bibcode: 1978PNAS...75.4744J.

- "ERK1 and ERK2, two microtubule-associated protein 2 kinases, mediate the phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase at serine-31 in situ". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 89 (6): 2365–9. Mar 1992. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.6.2365. PMID 1347949. Bibcode: 1992PNAS...89.2365H.

- "Phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase in situ at serine 8, 19, 31, and 40". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 265 (20): 11682–91. Jul 1990. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)38451-0. PMID 1973163.

- "Localization of the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene to 11p15: gene duplication and evolution of metabolic pathways". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics 42 (1–2): 29–32. 1986. doi:10.1159/000132246. PMID 2872999.

- "A single human gene encoding multiple tyrosine hydroxylases with different predicted functional characteristics". Nature 326 (6114): 707–11. 1987. doi:10.1038/326707a0. PMID 2882428. Bibcode: 1987Natur.326..707G.

- "Isolation of a novel cDNA clone for human tyrosine hydroxylase: alternative RNA splicing produces four kinds of mRNA from a single gene". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 146 (3): 971–5. Aug 1987. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(87)90742-X. PMID 2887169.

- "Isolation of a full-length cDNA clone encoding human tyrosine hydroxylase type 3". Nucleic Acids Research 15 (16): 6733. Aug 1987. doi:10.1093/nar/15.16.6733. PMID 2888085.

- "Isolation and characterization of the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene: identification of 5' alternative splice sites responsible for multiple mRNAs". Biochemistry 26 (22): 6910–4. Nov 1987. doi:10.1021/bi00396a007. PMID 2892528.

- "Analysis of the 5' region of the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene: combinatorial patterns of exon splicing generate multiple regulated tyrosine hydroxylase isoforms". Journal of Neurochemistry 50 (3): 988–91. Mar 1988. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb03009.x. PMID 2892893.

- "Expression of human tyrosine hydroxylase cDNA in invertebrate cells using a baculovirus vector". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 263 (15): 7406–10. May 1988. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68656-9. PMID 2896667.

- "Structure of the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene: alternative splicing from a single gene accounts for generation of four mRNA types". Journal of Biochemistry 103 (6): 907–12. Jun 1988. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122386. PMID 2902075.

- "Characterization of rat and human tyrosine hydroxylase genes: functional expression of both promoters in neuronal and non-neuronal cell types". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 157 (3): 1341–7. Dec 1988. doi:10.1016/S0006-291X(88)81022-2. PMID 2905129.

- "Phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase by calmodulin-dependent multiprotein kinase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 259 (22): 13680–3. Nov 1984. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)89798-8. PMID 6150037.

- "Targeted disruption of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene reveals that catecholamines are required for mouse fetal development". Nature 374 (6523): 640–3. Apr 1995. doi:10.1038/374640a0. PMID 7715703. Bibcode: 1995Natur.374..640Z.

- "Frequent sequence variant in the human tyrosine hydroxylase gene". Human Genetics 95 (6): 716. Jun 1995. doi:10.1007/BF00209496. PMID 7789962.

- "A point mutation in the tyrosine hydroxylase gene associated with Segawa's syndrome". Human Genetics 95 (1): 123–5. Jan 1995. doi:10.1007/BF00225091. PMID 7814018.

- "Recessively inherited L-DOPA-responsive dystonia caused by a point mutation (Q381K) in the tyrosine hydroxylase gene". Human Molecular Genetics 4 (7): 1209–12. Jul 1995. doi:10.1093/hmg/4.7.1209. PMID 8528210.

External links

- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Tyrosine Hydroxylase Deficiency including Tyrosine Hydroxylase-Deficient Dopa-Responsive Dystonia or Segawa Syndrome and Autosomal Recessive Infantile Parkinsonism

- Tyrosine+hydroxylase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

|