Astronomy:55637 Uni

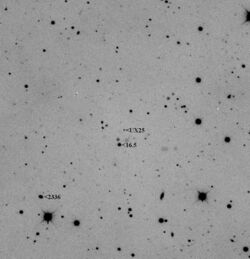

Uni and Tinia as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope | |

| Discovery[1] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Spacewatch (291) |

| Discovery site | Kitt Peak National Obs. |

| Discovery date | 30 October 2002 |

| Designations | |

Designation | (55637) Uni |

| Named after | Uni |

| 2002 UX25 | |

| Minor planet category | Cubewano (MPC)[2] Extended (DES)[3] |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| Epoch 5 May 2025 (JD 2460800.5) | |

| Uncertainty parameter 0 | |

| Observation arc | 33.35 yr (12,182 days) |

| Earliest precovery date | 12 October 1991 |

| |{{{apsis}}}|helion}} | 49.291 AU |

| |{{{apsis}}}|helion}} | 36.716 AU |

| 43.003 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.1462 |

| Orbital period | 282.01 yr (103,005 days) |

| Average Orbital speed | 4.54 km/s |

| Mean anomaly | 309.49° |

| Mean motion | 0° 0m 12.24s / day |

| Inclination | 19.400° |

| Longitude of ascending node | 204.57° |

| |{{{apsis}}}|helion}} | ≈ 5 September 2066[4] ±3 days |

| 275.27° | |

| Known satellites | 1 (Tinia) |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mean diameter | 659±38 km[5] |

| Mass | (1.25±0.03)×1020 kg[6] |

| Mean density | 0.82±0.11 g/cm3 (assuming equal densities for primary and satellite)[6] 0.80±0.13 g/cm3[5] |

| 0.075 m/s2 | |

| 0.227 km/s | |

| Rotation period | 14.382±0.001 h[7] |

| Albedo | 0.107+0.005 −0.008[8] 0.1±0.01[5] |

| Physics | ≈ 43 K |

Spectral type | B–V=1.007±0.043[9] V−R=0.540±0.030[9] V−I=1.046±0.034[9] |

| Apparent magnitude | 19.8 [10] |

| Absolute magnitude (H) | 3.87±0.02,[7] 4.0[1] |

55637 Uni (provisional designation 2002 UX25) is a large trans-Neptunian object that orbits the Sun in the Kuiper belt beyond Neptune. It briefly garnered scientific attention when it was found to have an unexpectedly low density of about 0.82 g/cm3.[11] It was discovered on 30 October 2002, by the Spacewatch program.[12]

Uni has an absolute magnitude of about 4.0,[1] and Spitzer Space Telescope results estimate it to be about 660 km in diameter.[5] The low density of this and many other mid-sized TNOs implies that they have never compressed into fully solid bodies, let alone differentiated or collapsed into hydrostatic equilibrium, and so are not likely to be dwarf planets.[13]

There is one known moon, Tinia, discovered in 2005.

Numbering and naming

Uni was numbered (55637) by the Minor Planet Center on 16 February 2003 (M.P.C. 47763).[14] On 1 September 2025, the object was named after Uni, the Etruscan goddess of love and fertility.[15]

Classification

Uni has a perihelion of 36.7 AU,[1] which it will next reach in 2065.[1] As of 2020, Uni is 40 AU from the Sun.[10]

The Minor Planet Center classifies Uni as a cubewano[2] while the Deep Ecliptic Survey (DES) classifies it as scattered-extended.[3] The DES using a 10 My integration (last observation: 2009-10-22) shows it with a minimum perihelion (qmin) distance of 36.3 AU.[3]

It has been observed 212 times with precovery images dating back to 1991.[1]

Physical characteristics

A variability of the visual brightness was detected which could be fit to a period of 14.38 or 16.78 h (depending on a single-peaked or double peaked curve).[16] The light-curve amplitude is ΔM = 0.21±0.06.[7]

The analysis of combined thermal radiometry of Uni from measurements by the Spitzer Space Telescope and Herschel Space Telescope indicates an effective diameter of 692 ± 23 km and albedo of 0.107+0.005−0.008.[17] Assuming equal albedos for the primary and secondary it leads to the size estimates of ~664 km and ~190 km, respectively. If the albedo of the secondary is half of that of the primary the estimates become ~640 and ~260 km, respectively.[6] Using an improved thermophysical model slightly different sizes were obtained for Uni and Tinia: 659 km and 230 km, respectively.[5]

Uni has red featureless spectrum in the visible and near-infrared but has a negative slope in the K-band, which may indicate the presence of the methanol compounds on the surface.[8] It is redder than Varuna, unlike its neutral-colored "twin" 2002 TX300, in spite of similar brightness and orbital elements.

Composition

With a density of 0.82 g/cm3, assuming that the primary and satellite have the same density, Uni is one of the largest known solid objects in the Solar System that is less dense than water.[11] Why this should be is not well understood, because objects of its size in the Kuiper belt often contain a fair amount of rock and are hence pretty dense. To have a similar composition to others large KBOs, it would have to be exceptionally porous, which was believed to be unlikely given the compactability of water ice;[6] this low density thus astonished astronomers.[11] Studies by Grundy et al. suggest that at the low temperatures that prevail beyond Neptune, ice is brittle and can support significant porosity in objects significantly larger than Uni, particularly if rock is present; the low density could thus be a consequence of this object failing to warm sufficiently during its formation to significantly deform the ice and fill these pore spaces.[18]

| Material | Density (g/cm3) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Settled snow | 0.2–0.3 | [19] |

| Slush/firn | 0.35–0.9 | [19] |

| Uni | 0.82 | [6] |

| Glacier ice | 0.83–0.92 | [19] |

| Tethys | 0.984 | [20] |

| Liquid water | 1 | [19] |

See also

- 229762 Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà – mid-sized trans-Neptunian object with a moon and a similarly low density of 1.0 g/cm3[21]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 55637 (2002 UX25)". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi?sstr=2055637.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "MPEC 2009-C70 :Distant Minor Planets (2009 FEB. 28.0 TT)". Minor Planet Center. 2009-02-10. https://www.minorplanetcenter.net/mpec/K09/K09C70.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Marc W. Buie. "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 55637". SwRI (Space Science Department). http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~buie/kbo/astrom/55637.html.

- ↑ JPL Horizons Observer Location: @sun (Perihelion occurs when deldot changes from negative to positive. Uncertainty in time of perihelion is 3-sigma.)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Brown, Michael E.; Butler, Bryan J. (20 June 2017). "The Density of Mid-sized Kuiper Belt Objects from ALMA Thermal Observations". The Astronomical Journal 154 (1): 19. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa6346. Bibcode: 2017AJ....154...19B.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 M.E. Brown (2013). "The density of mid-sized Kuiper belt object 2002 UX25 and the formation of the dwarf planets". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 778 (2): L34. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/778/2/L34. Bibcode: 2013ApJ...778L..34B.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "(55637) 2002 UX25". http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/astro/astmoons/am-55637.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Fornasier, S. et al. (2013). "TNOs are Cool: A survey of the trans-Neptunian region. VIII. Combined Herschel PACS and SPIRE observations of 9 bright targets at 70–500 μm.". Astronomy & Astrophysics 555: A92. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321329. Bibcode: 2013A&A...555A..15F.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hainaut, O. R.; Boehnhardt, H.; Protopapa, S. (October 2012). "Colours of minor bodies in the outer solar system. II. A statistical analysis revisited". Astronomy & Astrophysics 546: 20. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219566. Bibcode: 2012A&A...546A.115H. https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/pdf/2012/10/aa19566-12.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "AstDys (55637) 2002UX25 Ephemerides". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. https://newton.spacedys.com/astdys/index.php?pc=1.1.3.0&n=2002UX25.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cowen, Ron (2013). "Astronomers surprised by large space rock less dense than water". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14135.

- ↑ Marsden, Brian G. (2002-11-01). "MPEC 2002-V08 : 2002 UX25". IAU Minor Planet Center. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. https://www.minorplanetcenter.net/mpec/K02/K02V08.html.

- ↑ W.M. Grundy, K.S. Noll, M.W. Buie, S.D. Benecchi, D. Ragozzine & H.G. Roe, 'The Mutual Orbit, Mass, and Density of Transneptunian Binary Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà ((229762) 2007 UK126)', Icarus (forthcoming, available online 30 March 2019) DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037,

- ↑ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. https://www.minorplanetcenter.net/iau/ECS/MPCArchive/MPCArchive_TBL.html.

- ↑ "WGSBN Bulletin (Vol. 5, No. 20)". IAU. 2025-09-01. p. 6. https://www.wgsbn-iau.org/files/Bulletins/V005/WGSBNBull_V005_020.pdf.

- ↑ Rousselot, P.; Petit, J.-M.; Poulet, F.; Sergeev, A. Photometric study of Centaur (60558) 2000 EC98 and trans-neptunian object (55637) 2002 UX25 at different phase angles, Icarus, 176, (2005) pp. 478–491.Abstract.

- ↑ John Stansberry; Will Grundy; Mike Brown; Dale Cruikshank; John Spencer; David Trilling et al. (2008). "Physical Properties of Kuiper Belt and Centaur Objects: Constraints from Spitzer Space Telescope". in M. Antonietta Barucci. The Solar System Beyond Neptune. University of Arizona press. pp. 161–179. ISBN 978-0-8165-2755-7. Bibcode: 2008ssbn.book..161S. http://www.lpi.usra.edu/books/ssbn2008/7017.pdf.

- ↑ "The Mutual Orbit, Mass, and Density of Transneptunian Binary". 7 April 2019. http://www2.lowell.edu/~grundy/abstracts/preprints/2019.G-G.pdf.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 "Typical densities of snow and ice (kg/m3)". http://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/Contexts/Icy-Ecosystems/Looking-closer/Snow-and-ice-density.

- ↑ Roatsch Jaumann et al. 2009, p. 765, Tables 24.1–2

- ↑ Grundy, W. M.; Noll, K. S.; Buie, M. W.; Benecchi, S. D.; Ragozzine, D.; Roe, H. G. (December 2019). "The Mutual Orbit, Mass, and Density of Transneptunian Binary Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà ((229762) 2007 UK126)". Icarus 334: 30–38. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.037. Bibcode: 2019Icar..334...30G. http://www2.lowell.edu/users/grundy/abstracts/preprints/2019.G-G.pdf.

External links

- MPEC 2002-V08

- Astronomers surprised by large space rock less dense than water, Ron Cowen, Nature, 13 November 2013

- Scientist finds medium sized Kuiper belt object less dense than water, Bob Yirka, Phys.org, 14 November 2013

- 55637 Uni at AstDyS-2, Asteroids—Dynamic Site

- 55637 Uni at the JPL Small-Body Database

|