Physics:Quantum chaos

| Part of a series on |

| Quantum mechanics |

|---|

Quantum chaos is a branch of physics which studies how chaotic classical dynamical systems can be described in terms of quantum theory. The primary question that quantum chaos seeks to answer is: "What is the relationship between quantum mechanics and classical chaos?" The correspondence principle states that classical mechanics is the classical limit of quantum mechanics, specifically in the limit as the ratio of Planck's constant to the action of the system tends to zero. If this is true, then there must be quantum mechanisms underlying classical chaos (although this may not be a fruitful way of examining classical chaos). If quantum mechanics does not demonstrate an exponential sensitivity to initial conditions, how can exponential sensitivity to initial conditions arise in classical chaos, which must be the correspondence principle limit of quantum mechanics?[1][2]

In seeking to address the basic question of quantum chaos, several approaches have been employed:

- Development of methods for solving quantum problems where the perturbation cannot be considered small in perturbation theory and where quantum numbers are large.

- Correlating statistical descriptions of eigenvalues (energy levels) with the classical behavior of the same Hamiltonian (system).

- Study of probability distribution of individual eigenstates (see scars and Quantum ergodicity).

- Semiclassical methods such as periodic-orbit theory connecting the classical trajectories of the dynamical system with quantum features.

- Direct application of the correspondence principle.

History

During the first half of the twentieth century, chaotic behavior in mechanics was recognized (as in the three-body problem in celestial mechanics), but not well understood. The foundations of modern quantum mechanics were laid in that period, essentially leaving aside the issue of the quantum-classical correspondence in systems whose classical limit exhibit chaos.

Approaches

Questions related to the correspondence principle arise in many different branches of physics, ranging from nuclear to atomic, molecular and solid-state physics, and even to acoustics, microwaves and optics. However, classical-quantum correspondence in chaos theory is not always possible. Thus, some versions of the classical butterfly effect do not have counterparts in quantum mechanics.[5]

Important observations often associated with classically chaotic quantum systems are spectral level repulsion, dynamical localization in time evolution (e.g. ionization rates of atoms), and enhanced stationary wave intensities in regions of space where classical dynamics exhibits only unstable trajectories (as in scattering). In the semiclassical approach of quantum chaos, phenomena are identified in spectroscopy by analyzing the statistical distribution of spectral lines and by connecting spectral periodicities with classical orbits. Other phenomena show up in the time evolution of a quantum system, or in its response to various types of external forces. In some contexts, such as acoustics or microwaves, wave patterns are directly observable and exhibit irregular amplitude distributions.

Quantum chaos typically deals with systems whose properties need to be calculated using either numerical techniques or approximation schemes (see e.g. Dyson series). Simple and exact solutions are precluded by the fact that the system's constituents either influence each other in a complex way, or depend on temporally varying external forces.

Quantum mechanics in non-perturbative regimes

For conservative systems, the goal of quantum mechanics in non-perturbative regimes is to find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a Hamiltonian of the form

where is separable in some coordinate system, is non-separable in the coordinate system in which is separated, and is a parameter which cannot be considered small. Physicists have historically approached problems of this nature by trying to find the coordinate system in which the non-separable Hamiltonian is smallest and then treating the non-separable Hamiltonian as a perturbation.

Finding constants of motion so that this separation can be performed can be a difficult (sometimes impossible) analytical task. Solving the classical problem can give valuable insight into solving the quantum problem. If there are regular classical solutions of the same Hamiltonian, then there are (at least) approximate constants of motion, and by solving the classical problem, we gain clues how to find them.

Other approaches have been developed in recent years. One is to express the Hamiltonian in different coordinate systems in different regions of space, minimizing the non-separable part of the Hamiltonian in each region. Wavefunctions are obtained in these regions, and eigenvalues are obtained by matching boundary conditions.

Another approach is numerical matrix diagonalization. If the Hamiltonian matrix is computed in any complete basis, eigenvalues and eigenvectors are obtained by diagonalizing the matrix. However, all complete basis sets are infinite, and we need to truncate the basis and still obtain accurate results. These techniques boil down to choosing a truncated basis from which accurate wavefunctions can be constructed. The computational time required to diagonalize a matrix scales as , where is the dimension of the matrix, so it is important to choose the smallest basis possible from which the relevant wavefunctions can be constructed. It is also convenient to choose a basis in which the matrix is sparse and/or the matrix elements are given by simple algebraic expressions because computing matrix elements can also be a computational burden.

A given Hamiltonian shares the same constants of motion for both classical and quantum dynamics. Quantum systems can also have additional quantum numbers corresponding to discrete symmetries (such as parity conservation from reflection symmetry). However, if we merely find quantum solutions of a Hamiltonian which is not approachable by perturbation theory, we may learn a great deal about quantum solutions, but we have learned little about quantum chaos. Nevertheless, learning how to solve such quantum problems is an important part of answering the question of quantum chaos.

Correlating statistical descriptions of quantum mechanics with classical behavior

Statistical measures of quantum chaos were born out of a desire to quantify spectral features of complex systems. Random matrix theory was developed in an attempt to characterize spectra of complex nuclei. The remarkable result is that the statistical properties of many systems with unknown Hamiltonians can be predicted using random matrices of the proper symmetry class. Furthermore, random matrix theory also correctly predicts statistical properties of the eigenvalues of many chaotic systems with known Hamiltonians. This makes it useful as a tool for characterizing spectra which require large numerical efforts to compute.

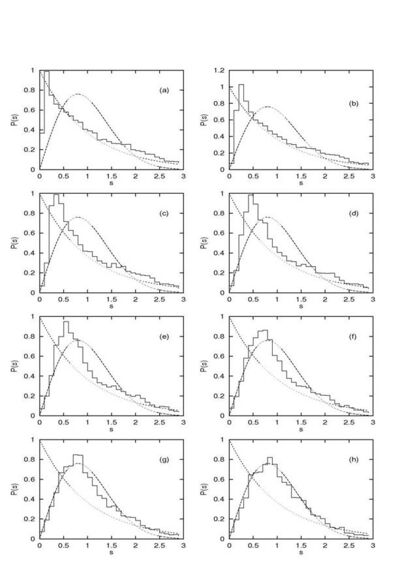

A number of statistical measures are available for quantifying spectral features in a simple way. It is of great interest whether or not there are universal statistical behaviors of classically chaotic systems. The statistical tests mentioned here are universal, at least to systems with few degrees of freedom (Berry and Tabor[6] have put forward strong arguments for a Poisson distribution in the case of regular motion and Heusler et al.[7] present a semiclassical explanation of the so-called Bohigas–Giannoni–Schmit conjecture which asserts universality of spectral fluctuations in chaotic dynamics). The nearest-neighbor distribution (NND) of energy levels is relatively simple to interpret and it has been widely used to describe quantum chaos.

Qualitative observations of level repulsions can be quantified and related to the classical dynamics using the NND, which is believed to be an important signature of classical dynamics in quantum systems. It is thought that regular classical dynamics is manifested by a Poisson distribution of energy levels:

In addition, systems which display chaotic classical motion are expected to be characterized by the statistics of random matrix eigenvalue ensembles. For systems invariant under time reversal, the energy-level statistics of a number of chaotic systems have been shown to be in good agreement with the predictions of the Gaussian orthogonal ensemble (GOE) of random matrices, and it has been suggested that this phenomenon is generic for all chaotic systems with this symmetry. If the normalized spacing between two energy levels is , the normalized distribution of spacings is well approximated by

Many Hamiltonian systems which are classically integrable (non-chaotic) have been found to have quantum solutions that yield nearest neighbor distributions which follow the Poisson distributions. Similarly, many systems which exhibit classical chaos have been found with quantum solutions yielding a Wigner-Dyson distribution, thus supporting the ideas above. One notable exception is diamagnetic lithium which, though exhibiting classical chaos, demonstrates Wigner (chaotic) statistics for the even-parity energy levels and nearly Poisson (regular) statistics for the odd-parity energy level distribution.[8]

Semiclassical methods

Periodic orbit theory

Periodic-orbit theory gives a recipe for computing spectra from the periodic orbits of a system. In contrast to the Einstein–Brillouin–Keller method of action quantization, which applies only to integrable or near-integrable systems and computes individual eigenvalues from each trajectory, periodic-orbit theory is applicable to both integrable and non-integrable systems and asserts that each periodic orbit produces a sinusoidal fluctuation in the density of states.

The principal result of this development is an expression for the density of states which is the trace of the semiclassical Green's function and is given by the Gutzwiller trace formula:

Recently there was a generalization of this formula for arbitrary matrix Hamiltonians that involves a Berry phase-like term stemming from spin or other internal degrees of freedom.[9] The index distinguishes the primitive periodic orbits: the shortest period orbits of a given set of initial conditions. is the period of the primitive periodic orbit and is its classical action. Each primitive orbit retraces itself, leading to a new orbit with action and a period which is an integral multiple of the primitive period. Hence, every repetition of a periodic orbit is another periodic orbit. These repetitions are separately classified by the intermediate sum over the indices . is the orbit's Maslov index. The amplitude factor, , represents the square root of the density of neighboring orbits. Neighboring trajectories of an unstable periodic orbit diverge exponentially in time from the periodic orbit. The quantity characterizes the instability of the orbit. A stable orbit moves on a torus in phase space, and neighboring trajectories wind around it. For stable orbits, becomes , where is the winding number of the periodic orbit. , where is the number of times that neighboring orbits intersect the periodic orbit in one period. This presents a difficulty because at a classical bifurcation. This causes that orbit's contribution to the energy density to diverge. This also occurs in the context of photo-absorption spectrum.

Using the trace formula to compute a spectrum requires summing over all of the periodic orbits of a system. This presents several difficulties for chaotic systems: 1) The number of periodic orbits proliferates exponentially as a function of action. 2) There are an infinite number of periodic orbits, and the convergence properties of periodic-orbit theory are unknown. This difficulty is also present when applying periodic-orbit theory to regular systems. 3) Long-period orbits are difficult to compute because most trajectories are unstable and sensitive to roundoff errors and details of the numerical integration.

Gutzwiller applied the trace formula to approach the anisotropic Kepler problem (a single particle in a potential with an anisotropic mass tensor) semiclassically. He found agreement with quantum computations for low lying (up to ) states for small anisotropies by using only a small set of easily computed periodic orbits, but the agreement was poor for large anisotropies.

The figures above use an inverted approach to testing periodic-orbit theory. The trace formula asserts that each periodic orbit contributes a sinusoidal term to the spectrum. Rather than dealing with the computational difficulties surrounding long-period orbits to try to find the density of states (energy levels), one can use standard quantum mechanical perturbation theory to compute eigenvalues (energy levels) and use the Fourier transform to look for the periodic modulations of the spectrum which are the signature of periodic orbits. Interpreting the spectrum then amounts to finding the orbits which correspond to peaks in the Fourier transform.

Rough sketch on how to arrive at the Gutzwiller trace formula

- Start with the semiclassical approximation of the time-dependent Green's function (the Van Vleck propagator).

- Realize that for caustics the description diverges and use the insight by Maslov (approximately Fourier transforming to momentum space (stationary phase approximation with h a small parameter) to avoid such points and afterwards transforming back to position space can cure such a divergence, however gives a phase factor).

- Transform the Greens function to energy space to get the energy dependent Greens function (again approximate Fourier transform using the stationary phase approximation). New divergences might pop up that need to be cured using the same method as step 3

- Use (tracing over positions) and calculate it again in stationary phase approximation to get an approximation for the density of states .

Note: Taking the trace tells you that only closed orbits contribute, the stationary phase approximation gives you restrictive conditions each time you make it. In step 4 it restricts you to orbits where initial and final momentum are the same i.e. periodic orbits. Often it is nice to choose a coordinate system parallel to the direction of movement, as it is done in many books.

Closed orbit theory

Closed-orbit theory was developed by J.B. Delos, M.L. Du, J. Gao, and J. Shaw. It is similar to periodic-orbit theory, except that closed-orbit theory is applicable only to atomic and molecular spectra and yields the oscillator strength density (observable photo-absorption spectrum) from a specified initial state whereas periodic-orbit theory yields the density of states.

Only orbits that begin and end at the nucleus are important in closed-orbit theory. Physically, these are associated with the outgoing waves that are generated when a tightly bound electron is excited to a high-lying state. For Rydberg atoms and molecules, every orbit which is closed at the nucleus is also a periodic orbit whose period is equal to either the closure time or twice the closure time.

According to closed-orbit theory, the average oscillator strength density at constant is given by a smooth background plus an oscillatory sum of the form

is a phase that depends on the Maslov index and other details of the orbits. is the recurrence amplitude of a closed orbit for a given initial state (labeled ). It contains information about the stability of the orbit, its initial and final directions, and the matrix element of the dipole operator between the initial state and a zero-energy Coulomb wave. For scaling systems such as Rydberg atoms in strong fields, the Fourier transform of an oscillator strength spectrum computed at fixed as a function of is called a recurrence spectrum, because it gives peaks which correspond to the scaled action of closed orbits and whose heights correspond to .

Closed-orbit theory has found broad agreement with a number of chaotic systems, including diamagnetic hydrogen, hydrogen in parallel electric and magnetic fields, diamagnetic lithium, lithium in an electric field, the ion in crossed and parallel electric and magnetic fields, barium in an electric field, and helium in an electric field.

One-dimensional systems and potential

For the case of one-dimensional system with the boundary condition the density of states obtained from the Gutzwiller formula is related to the inverse of the potential of the classical system by here is the density of states and V(x) is the classical potential of the particle, the half derivative of the inverse of the potential is related to the density of states as in the Wu-Sprung potential.

Recent directions

One open question remains understanding quantum chaos in systems that have finite-dimensional local Hilbert spaces for which standard semiclassical limits do not apply. Recent works allowed for studying analytically such quantum many-body systems.[10][11]

The traditional topics in quantum chaos concerns spectral statistics (universal and non-universal features), and the study of eigenfunctions of various chaotic Hamiltonian. For example, before the existence of scars was reported, eigenstates of a classically chaotic system were conjectured to fill the available phase space evenly, up to random fluctuations and energy conservation (Quantum ergodicity). However, a quantum eigenstate of a classically chaotic system can be scarred:[12] the probability density of the eigenstate is enhanced in the neighborhood of a periodic orbit, above the classical, statistically expected density along the orbit (scars). In particular, scars are both a striking visual example of classical-quantum correspondence away from the usual classical limit, and a useful example of a quantum suppression of chaos. For example, this is evident in the perturbation-induced quantum scarring:[13][14][15][16][17] More specifically, in quantum dots perturbed by local potential bumps (impurities), some of the eigenstates are strongly scarred along periodic orbits of unperturbed classical counterpart.

Further studies concern the parametric () dependence of the Hamiltonian, as reflected in e.g. the statistics of avoided crossings, and the associated mixing as reflected in the (parametric) local density of states (LDOS). There is vast literature on wavepacket dynamics, including the study of fluctuations, recurrences, quantum irreversibility issues etc. Special place is reserved to the study of the dynamics of quantized maps: the standard map and the kicked rotator are considered to be prototype problems.

Works are also focused in the study of driven chaotic systems,[18] where the Hamiltonian is time dependent, in particular in the adiabatic and in the linear response regimes. There is also significant effort focused on formulating ideas of quantum chaos for strongly-interacting many-body quantum systems far from semi-classical regimes as well as a large effort in quantum chaotic scattering.[19]

Berry–Tabor conjecture

In 1977, Berry and Tabor made a still open "generic" mathematical conjecture which, stated roughly, is: In the "generic" case for the quantum dynamics of a geodesic flow on a compact Riemann surface, the quantum energy eigenvalues behave like a sequence of independent random variables provided that the underlying classical dynamics is completely integrable.[20][21][22]

See also

References

- ↑ Quantum Signatures of Chaos, Fritz Haake, Edition: 2, Springer, 2001, ISBN 3-540-67723-2, ISBN 978-3-540-67723-9.

- ↑ Michael Berry, "Quantum Chaology", pp 104-5 of Quantum: a guide for the perplexed by Jim Al-Khalili (Weidenfeld and Nicolson 2003), http://www.physics.bristol.ac.uk/people/berry_mv/the_papers/Berry358.pdf .

- ↑ Closed Orbit Bifurcations in Continuum Stark Spectra, M Courtney, H Jiao, N Spellmeyer, D Kleppner, J Gao, JB Delos, Phys. Rev. Lett. 27, 1538 (1995).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Classical, semiclassical, and quantum dynamics of lithium in an electric field, M Courtney, N Spellmeyer, H Jiao, D Kleppner, Phys Rev A 51, 3604 (1995).

- ↑ Yan, Bin; Sinitsyn, Nikolai A. (2020). "Recovery of Damaged Information and the Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators". Physical Review Letters 125 (4): 040605. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.040605. PMID 32794812. Bibcode: 2020PhRvL.125d0605Y.

- ↑ M.V. Berry and M. Tabor, Proc. Roy. Soc. London A 356, 375, 1977

- ↑ Heusler, S., S. Müller, A. Altland, P. Braun, and F. Haake, 2007, Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 044103

- ↑ Courtney, M and Kleppner, D [1], Core-induced chaos in diamagnetic lithium, PRA 53, 178, 1996

- ↑ Vogl, M.; Pankratov, O.; Shallcross, S. (2017-07-27). "Semiclassics for matrix Hamiltonians: The Gutzwiller trace formula with applications to graphene-type systems". Physical Review B 96 (3): 035442. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.96.035442. Bibcode: 2017PhRvB..96c5442V. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.035442.

- ↑ Kos, Pavel; Ljubotina, Marko; Prosen, Tomaž (2018-06-08). "Many-Body Quantum Chaos: Analytic Connection to Random Matrix Theory". Physical Review X 8 (2): 021062. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.8.021062. Bibcode: 2018PhRvX...8b1062K.

- ↑ Chan, Amos; De Luca, Andrea; Chalker, J. T. (2018-11-08). "Solution of a Minimal Model for Many-Body Quantum Chaos" (in en). Physical Review X 8 (4): 041019. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.8.041019. ISSN 2160-3308. Bibcode: 2018PhRvX...8d1019C.

- ↑ Heller, Eric J. (1984-10-15). "Bound-State Eigenfunctions of Classically Chaotic Hamiltonian Systems: Scars of Periodic Orbits". Physical Review Letters 53 (16): 1515–1518. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1515. Bibcode: 1984PhRvL..53.1515H. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.53.1515.

- ↑ Keski-Rahkonen, J.; Ruhanen, A.; Heller, E. J.; Räsänen, E. (2019-11-21). "Quantum Lissajous Scars". Physical Review Letters 123 (21): 214101. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.214101. PMID 31809168. Bibcode: 2019PhRvL.123u4101K. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.123.214101.

- ↑ Luukko, Perttu J. J.; Drury, Byron; Klales, Anna; Kaplan, Lev; Heller, Eric J.; Räsänen, Esa (2016-11-28). "Strong quantum scarring by local impurities" (in en). Scientific Reports 6 (1): 37656. doi:10.1038/srep37656. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 27892510. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...637656L.

- ↑ Keski-Rahkonen, J.; Luukko, P. J. J.; Kaplan, L.; Heller, E. J.; Räsänen, E. (2017-09-20). "Controllable quantum scars in semiconductor quantum dots". Physical Review B 96 (9): 094204. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.96.094204. Bibcode: 2017PhRvB..96i4204K. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.094204.

- ↑ Keski-Rahkonen, J; Luukko, P J J; Åberg, S; Räsänen, E (2019-01-21). "Effects of scarring on quantum chaos in disordered quantum wells" (in en). Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 31 (10): 105301. doi:10.1088/1361-648x/aaf9fb. ISSN 0953-8984. PMID 30566927. Bibcode: 2019JPCM...31j5301K. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aaf9fb.

- ↑ Keski-Rahkonen, Joonas (2020) (in en). Quantum Chaos in Disordered Two-Dimensional Nanostructures. Tampere University. ISBN 978-952-03-1699-0. https://trepo.tuni.fi/handle/10024/123296.

- ↑ Driven chaotic mesoscopic systems,dissipation and decoherence, in Proceedings of the 38th Karpacz Winter School of Theoretical Physics, Edited by P. Garbaczewski and R. Olkiewicz (Springer, 2002). arXiv:quant-ph/0403061

- ↑ Gaspard, Pierre (2014). "Quantum chaotic scattering" (in en). Scholarpedia 9 (6): 9806. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.9806. ISSN 1941-6016. Bibcode: 2014SchpJ...9.9806G.

- ↑ Marklof, Jens, The Berry–Tabor conjecture, http://www.maths.bris.ac.uk/~majm/bib/3ecm.pdf

- ↑ Barba, J.C. (2008). "The Berry–Tabor conjecture for spin chains of Haldane–Shastry type". EPL 83 (2): 27005. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/83/27005. Bibcode: 2008EL.....8327005B.

- ↑ Rudnick, Z. (Jan 2008). "What Is Quantum Chaos?". Notices of the AMS 55 (1): 32–34. https://www.ams.org/notices/200801/tx080100032p.pdf.

Further resources

- Martin C. Gutzwiller (1971). "Periodic Orbits and Classical Quantization Conditions". Journal of Mathematical Physics 12 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1063/1.1665596. Bibcode: 1971JMP....12..343G.

- Martin C. Gutzwiller, Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics, (1990) Springer-Verlag, New York ISBN 0-387-97173-4.

- Hans-Jürgen Stöckmann, Quantum Chaos: An Introduction, (1999) Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-59284-4.

- Eugene Paul Wigner; Dirac, P. A. M. (1951). "On the statistical distribution of the widths and spacings of nuclear resonance levels". Mathematical Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 47 (4): 790. doi:10.1017/S0305004100027237. Bibcode: 1951PCPS...47..790W.

- Fritz Haake, Quantum Signatures of Chaos 2nd ed., (2001) Springer-Verlag, New York ISBN 3-540-67723-2.

- Karl-Fredrik Berggren and Sven Aberg, "Quantum Chaos Y2K Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 116" (2001) ISBN 978-981-02-4711-9

- L. E. Reichl, "The Transition to Chaos: In Conservative Classical Systems : Quantum Manifestations", Springer (2004), ISBN 978-0387987880

External links

- Quantum Chaos by Martin Gutzwiller (1992 and 2008, Scientific American)

- Quantum Chaos Martin Gutzwiller Scholarpedia 2(12):3146. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3146

- Category:Quantum Chaos Scholarpedia

- What is... Quantum Chaos by Ze'ev Rudnick (January 2008, Notices of the American Mathematical Society)

- Brian Hayes, "The Spectrum of Riemannium"; American Scientist Volume 91, Number 4, July–August, 2003 pp. 296–300. Discusses relation to the Riemann zeta function.

- Eigenfunctions in chaotic quantum systems by Arnd Bäcker.

- ChaosBook.org

|