Biology:Atorvastatin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˌtɔːrvəˈstætən/ |

| Trade names | Lipitor, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a600045 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 12% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 14 hours |

| Excretion | Bile duct |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

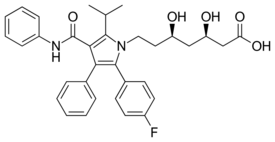

| Formula | C33H35FN2O5 |

| Molar mass | 558.650 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Atorvastatin, sold under the brand name Lipitor among others, is a statin medication used to prevent cardiovascular disease in those at high risk and to treat abnormal lipid levels.[3] For the prevention of cardiovascular disease, statins are a first-line treatment.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include joint pain, diarrhea, heartburn, nausea, and muscle pains.[3] Serious side effects may include rhabdomyolysis, liver problems, and diabetes.[3] Use during pregnancy may harm the fetus.[3] Like all statins, atorvastatin works by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, an enzyme found in the liver that plays a role in producing cholesterol.[3]

Atorvastatin was patented in 1986, and approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[3][4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[3][6] In 2021, it was the most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 116 million prescriptions.[7][8]

Medical uses

The primary uses of atorvastatin is for the treatment of dyslipidemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease:[9]

Dyslipidemia

- Hypercholesterolemia[10] (heterozygous familial and nonfamilial) and mixed dyslipidemia (Fredrickson types IIa and IIb) to reduce total cholesterol, LDL-C,[11] apo-B,[12] triglycerides[13] levels, and CRP[14] as well as increase HDL levels.

- Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia[10] in children

- Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia[10][15]

- Hypertriglyceridemia (Fredrickson Type IV)

- Primary dysbetalipoproteinemia (Fredrickson Type III)

- Combined hyperlipidemia[16]

Cardiovascular disease

- Primary prevention of heart attack, stroke, and need for revascularization procedures in people who have risk factors such as age, smoking, high blood pressure, low HDL-C, and a family history of early heart disease, but have not yet developed evidence of coronary artery disease.[2]

- Secondary prevention of myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina,[17][18] and revascularization in people with established coronary artery disease.[19][20]

- Myocardial infarction and stroke prevention in people with type 2 diabetes[21][22][23]

A 2014 meta-analysis showed high-dose statin therapy was significantly superior compared to moderate or low-intensity statin therapy in reducing plaque volume in patients with acute coronary syndrome.[24] The SATURN trial which compared the effects of high-dose atorvastatin and rosuvastatin also confirmed these findings.[25] Despite the high dosage, the 40 mg pravastatin study arm in the REVERSAL trial failed to halt plaque progression, which suggests other factors such as which statin is used, duration and location of the plaque may also affect plaque volume reduction and thereby plaque-stabilization.[26] Overall, plaque reduction should be considered as a surrogate endpoint and should not be directly used to determine clinical benefit of therapy.[25][26] Increased risk of adverse events should also be taken into account when considering high-dose statin therapy.[24][25][26]

Kidney disease

There is evidence from systematic review and meta-analyses that statins, particularly atorvastatin, reduce both decline in kidney function (eGFR) and the severity of protein excretion in urine,[27][28][29] with higher doses having greater effect.[28][29] Data is conflicting for whether statins reduce risk of kidney failure.[27] Statins, including atorvastatin, before heart surgery do not prevent acute kidney injury.[30]

Prior to contrast medium (CM) administration, pre-treatment with atorvastatin therapy can reduce the risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) in patients with pre-existing chronic kidney disease (CKD) (eGFR < 60mL/min/1.73m2) who undergo interventional procedures such as cardiac catheterisation, coronary angiography (CAG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[31][32][33] A meta-analysis of 21 RCTs confirmed that high dose (80 mg) atorvastatin therapy is more effective than regular dose or low dose statin therapy at preventing CI-AKI.[31] Atorvastatin therapy can also help to prevent in-hospital dialysis post CM administration, however there is no evidence that it reduces all-cause mortality associated with CI-AKI.[31][32] Overall, the evidence concludes that statin therapy, irrespective of the dose, is still more effective than no treatment or placebo at reducing the risk of CI-AKI.[31][32][33][34]

Administration

Statins (predominantly simvastatin) have been evaluated in clinical trials in combination with fibrates to manage dyslipidemia in patients who also have type 2 diabetes, and a high cardiovascular disease risk, however, there is limited clinical benefit noted for most cardiovascular outcomes [35][36]

While many short half-lives statin medications should be taken in the evening for optimal effect, atorvastatin tablets can be taken at any time of day due to its long half-life profile, as long as it is taken at the same time every day. This also potentially ensures better patient compliance. Some studies found evening dose of both short and long half-life statins were significantly superior to morning dose for lowering LDL-C.[37][38][39][40]

Specific populations

- Geriatric: Plasma concentrations of atorvastatin in healthy elderly subjects are higher than those in young adults, and clinical data suggests a greater degree of LDL-lowering at any dose for people in the population as compared to young adults.[2]

- Pediatric: Pharmacokinetic data is not available for this population.[2]

- Gender: Plasma concentrations are generally higher in women than in men, but there is no clinically significant difference in the extent of LDL reduction between men and women.[2]

- Kidney impairment: Kidney disease has no statistically significant influence on plasma concentrations of atorvastatin and dose adjustment considerations should only be made in context of the patient's overall health.[41][unreliable medical source][42][unreliable medical source]

- Hemodialysis: Although there has been moderate-to-high quality of evidence to show the lack of clear and significant clinical benefits of statins (including atorvastatin at a dose of 20mg) minimizing non-fatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality in adult patients on haemodialysis (including those with diabetes and/or pre-existing cardiovascular diseases) despite the clinically relevant reduction in total/LDL cholesterol levels,[43][unreliable medical source][44] there is evidence that haemodialysis patients who received moderate intensity statin therapy had a lower risk of all-cause mortality.[45]

- However, data (post hoc analysis) on atorvastatin has revealed that it may still be beneficial in reducing combined cardiac events, cardiac and all-cause mortality in those with a higher baseline LDL cholesterol >3.75 mmol/L.[46][unreliable medical source] While the SHARP study suggested that LDL cholesterol-lowering treatments (e.g. statin/ezetimibe combination) are effective in reducing the risks of major atherosclerotic events in the CKD patients including those on dialysis, the subgroup analysis of the haemodialysis patients had revealed no significant benefits.[47][unreliable medical source] Whether or not haemodialysis had any impact on the statin levels was not specifically addressed in these major trials.

- Hepatic Impairment: Increased drug levels can be seen in patients with advanced cirrhosis; specific precaution should be used in patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease.[2] Despite these concerns, a 2017 systematic review and analysis of available evidence has shown that statins, such as atorvastatin, are relatively safe to use in stable, asymptomatic cirrhosis and may even reduce the risk of liver disease progression and death.[48]

Contraindications

- Active liver disease: cholestasis, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatitis, and jaundice

- Pregnancy: Atorvastatin is unlikely to cause fetal anomalies but may be associated with low birth weight and preterm labour.[49]

- Breastfeeding: Small amounts of other statin medications have been found to pass into breast milk, although atorvastatin has not been studied, specifically.[2] Due to risk of disrupting a breastfeeding infant's metabolism of lipids, atorvastatin is not regarded as compatible with breastfeeding.[50]

- Markedly elevated CPK levels or if a myopathy is suspected or diagnosed after dosing of atorvastatin has begun. Very rarely, atorvastatin may cause rhabdomyolysis,[51] and it may be very serious leading to acute kidney injury due to myoglobinuria. When rhabdomyolysis is suspected or diagnosed, atorvastatin therapy is discontinued immediately.[52] The likelihood of developing a myopathy is increased by the co-administration of cyclosporine, fibric acid derivatives, erythromycin, niacin, and azole antifungals.[2]

Side effects

Major

- Type 2 diabetes is observed in a small number of people, and is an uncommon class effect of all statins.[53][54][55] It appears it may be more likely in people who were already at a higher risk of developing diabetes before starting a statin due to multiple risk factors, for example raised fasting glucose levels.[56] However, the benefits of statin therapy in preventing fatal and non-fatal stroke, fatal coronary heart disease, and non-fatal myocardial infarction are significant.[17] For most people the benefits of statin therapy far outweigh the risk of developing diabetes.[57] A 2010 meta-analysis demonstrated that every 255 people treated with a statin for four years – produced a reduction of 5.4 major coronary events and induced only one new case of diabetes.[57]

- In some case and clinical studies mild muscle pain or weakness have been reported (around 3%), compared to a placebo.[58][59] However, this increase was not related to statin therapy in 90% of cases in a large meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.[59] In patients taking higher statin doses, a similarly low increase in muscle pain and weakness was present (5%) with no clear evidence of a dose-response relationship. Duration of treatment with atorvastatin is unlikely to increase the risk of muscle-related side effects as most occur within the first year of treatment, after which the risk is not increased further.[59] The known cardiovascular benefits of atorvastatin over time outweigh the low risk of muscle-related side effects.[60][59]

- There is also an increased risk of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis when statins are taken over the long term.[61]

- Persistent liver enzyme abnormalities (usually elevated in hepatic transaminases) have been documented.[62] Elevations threefold greater than normal were recorded in 0.5% of people treated with atorvastatin 10 mg-80 mg rather than placebo.[63] Usage instructions in package inserts for this statin define the requirement that hepatic function be assessed with laboratory tests before beginning atorvastatin treatment and repeated periodically as clinically indicated - usually a clinicians' judgement. Package inserts for this statin recommend actions should liver abnormalities be detected, ultimately, this is the judgment of the prescribing physician.[2]

Common

The following have been shown to occur in 1–10% of people taking atorvastatin in clinical trials:

- Joint pain[2]

- Loose stools[2]

- Indigestion[2]

- Muscle pain[2]

- Nausea[2]

- Hyperglycemia Atorvastatin may increase fasting plasma glucose and regular blood sugar monitoring may be advised. [64][65][66]

Other

Cognitive

There have been rare reports of reversible memory loss and confusion with all statins, including atorvastatin; however, there has not been enough evidence to associate statin use with cognitive impairment, and the risks for cognition are likely outweighed by the beneficial effects of adherence to statin therapy on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease.[67][68][69][70]

Pancreatitis

There is some evidence that atorvastatin use may increase the risk of acute pancreatitis, in people who are already at a higher risk.[71][72] However, there is also evidence that atorvastatin use decreases the risk of acute pancreatitis in people with mild to moderate hypertriglyceridemia, by lowering triglyceride levels.[72]

Erectile dysfunction

Statins seem to have a positive effect on erectile dysfunction.[73][74]

Interactions

Fibrates are a class of drugs that can be used for severe or refractory mixed hyperlipidaemia in combination with statins or as monotherapy. Several studies suggest that the concomitant therapy of atorvastatin with drugs from the fibrate drug class (such as gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) can increase the risk of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis,[75][76][77][78] however other studies have found this to not be the case. [79][80]

Co-administration of atorvastatin with one of CYP3A4 inhibitors such as itraconazole,[81] telithromycin, and voriconazole, may increase serum concentrations of atorvastatin, which may lead to adverse reactions. This is less likely to happen with other CYP3A4 inhibitors such as diltiazem, erythromycin, fluconazole, ketoconazole, clarithromycin, cyclosporine, protease inhibitors, or verapamil,[82] and only rarely with other CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as amiodarone and aprepitant.[52] Often, bosentan, fosphenytoin, and phenytoin, which are CYP3A4 inducers, can decrease the plasma concentrations of atorvastatin. Only rarely, though, barbiturates, carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, oxcarbazepine, rifampin, and rifamycin,[83] which are also CYP3A4 inducers, can decrease the plasma concentrations of atorvastatin. Oral contraceptives increased AUC values for norethisterone and ethinylestradiol; these increases should be considered when selecting an oral contraceptive for a woman taking atorvastatin.[2]

Antacids can rarely decrease the plasma concentrations of statin medications, but do not affect the LDL-C-lowering efficacy.[84]

Niacin also is proved to increase the risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis.[52]

Some statins may also alter the concentrations of other medications, such as warfarin or digoxin, leading to alterations in effect or a requirement for clinical monitoring.[52] The increase in digoxin levels due to atorvastatin is a 1.2 fold elevation in the area under the curve (AUC), resulting in a minor drug-drug interaction. The American Heart Association states that the combination of digoxin and atorvastatin is reasonable.[85] In contrast to some other statins, atorvastatin does not interact with warfarin concentrations in a clinically meaningful way (similar to pitavastatin).[85]

Vitamin D supplementation lowers atorvastatin and active metabolite concentrations, yet synergistically reduces LDL and total cholesterol concentrations.[86]

Grapefruit juice components are known inhibitors of intestinal CYP3A4. Drinking grapefruit juice with atorvastatin may cause an increase in Cmax and area under the curve (AUC). This finding initially gave rise to concerns of toxicity, and in 2000, it was recommended that people taking atorvastatin should not consume grapefruit juice "in an unsupervised manner."[87] Small studies (using mostly young participants) examining the effects of grapefruit juice consumption on mainly lower doses of atorvastatin have shown that grapefruit juice increases blood levels of atorvastatin, which could increase the risk of adverse effects.[88][89][90] No studies assessing the impact of grapefruit juice consumption have included participants taking the highest dose of atorvastatin (80 mg daily),[88][89][90] which is often prescribed for people with a history of cardiovascular disease (such as heart attack or ischaemic stroke) or in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease. People taking atorvastatin should consult with their doctor or pharmacist before consuming grapefruit juice, as the effects of grapefruit juice consumption on atorvastatin will vary according to factors such as the amount and frequency of juice consumption in addition to differences in juice components, quality and method of juice preparation between different batches or brands.[91]

A few cases of myopathy have been reported when atorvastatin is given with colchicine.[2]

Mechanism of action

As with other statins, atorvastatin is a competitive inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase. Unlike most others, however, it is a completely synthetic compound. HMG-CoA reductase catalyzes the reduction of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) to mevalonate, which is the rate-limiting step in hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis. Inhibition of the enzyme decreases de novo cholesterol synthesis, increasing expression of low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDL receptors) on hepatocytes. This increases LDL uptake by the hepatocytes, decreasing the amount of LDL-cholesterol in the blood. Like other statins, atorvastatin also reduces blood levels of triglycerides and slightly increases levels of HDL-cholesterol.

In people with acute coronary syndrome, high-dose atorvastatin treatment may play a plaque-stabilizing role.[92][93] At high doses, statins have anti-inflammatory effects, incite reduction of the necrotic plaque core, and improve endothelial function, leading to plaque stabilization and, sometimes, plaque regression.[93][92] There is a similar thought process with using high-dose atorvastatin as a form of secondary thrombotic stroke recurrence prevention.[94][95][96]

Pharmacodynamics

The liver is the primary site of action of atorvastatin, as this is the principal site of both cholesterol synthesis and LDL clearance. It is the dosage of atorvastatin, rather than systemic medication concentration, which correlates with extent of LDL-C reduction.[2] In a Cochrane systematic review the dose-related magnitude of atorvastatin on blood lipids was determined. Over the dose range of 10 to 80 mg/day total cholesterol was reduced by 27.0% to 37.9%, LDL cholesterol by 37.1% to 51.7% and triglycerides by 18.0% to 28.3%.[97]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Atorvastatin undergoes rapid absorption when taken orally, with an approximate time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) of 1–2 h. The absolute bioavailability of the medication is about 14%, but the systemic availability for HMG-CoA reductase activity is approximately 30%. Atorvastatin undergoes high intestinal clearance and first-pass metabolism, which is the main cause for the low systemic availability. Administration of atorvastatin with food produces a 25% reduction in Cmax (rate of absorption) and a 9% reduction in AUC (extent of absorption), although food does not affect the plasma LDL-C-lowering efficacy of atorvastatin. Evening dose administration is known to reduce the Cmax and AUC by 30% each. However, time of administration does not affect the plasma LDL-C-lowering efficacy of atorvastatin.

Distribution

The mean volume of distribution of atorvastatin is approximately 381 L. It is highly protein bound (≥98%), and studies have shown it is likely secreted into human breastmilk.

Metabolism

Atorvastatin metabolism is primarily through cytochrome P450 3A4 hydroxylation to form active ortho- and parahydroxylated metabolites, as well as various beta-oxidation metabolites. The ortho- and parahydroxylated metabolites are responsible for 70% of systemic HMG-CoA reductase activity. The ortho-hydroxy metabolite undergoes further metabolism via glucuronidation. As a substrate for the CYP3A4 isozyme, it has shown susceptibility to inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4 to produce increased or decreased plasma concentrations, respectively. This interaction was tested in vitro with concurrent administration of erythromycin, a known CYP3A4 isozyme inhibitor, which resulted in increased plasma concentrations of atorvastatin. It is also an inhibitor of cytochrome 3A4.

Excretion

Atorvastatin is primarily eliminated via hepatic biliary excretion, with less than 2% recovered in the urine. Bile elimination follows hepatic and/or extrahepatic metabolism. There does not appear to be any entero-hepatic recirculation. Atorvastatin has an approximate elimination half-life of 14 hours. Noteworthy, the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity appears to have a half-life of 20–30 hours, which is thought to be due to the active metabolites. Atorvastatin is also a substrate of the intestinal P-glycoprotein efflux transporter, which pumps the medication back into the intestinal lumen during medication absorption.[52]

In hepatic insufficiency, plasma concentrations of atorvastatin are significantly affected by concurrent liver disease. People with Child-Pugh Stage A liver disease show a four-fold increase in both Cmax and AUC. People with Child Pugh stage B liver disease show a 16-fold increase in Cmax and an 11-fold increase in AUC.

Geriatric people (>65 years old) exhibit altered pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin compared to young adults, with mean AUC and Cmax values that are 40% and 30% higher, respectively. Additionally, healthy elderly people show a greater pharmacodynamic response to atorvastatin at any dose; therefore, this population may have lower effective doses.[2]

Pharmacogenetics

Several genetic polymorphisms may be linked to an increase in statin-related side effects with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the SLCO1B1 gene showing a 45 fold higher incidence of statin related myopathy[98] than people without the polymorphism.

There are several studies showing genetic variants and variable response to atorvastatin.[99][100] The polymorphisms that showed genome wide significance in Caucasian population were the SNPs in the apoE region; rs445925,[99] rs7412,[99][100] rs429358[100] and rs4420638[99] which showed variable LDL-c response depending on the genotype when treated with atorvastatin.[99][100] Another genetic variant that showed genome wide significance in Caucasians was the SNP rs10455872 in the LPA gene that lead to higher Lp(a) levels which cause an apparent lower LDL-c response to atorvastatin.[99] These studies were in Caucasian population, more research with a large cohort need to be conducted in different ethnicities to identify more polymorphisms that can affect atorvastatin pharmacokinetics and treatment response.[99]

Chemical synthesis

The first synthesis of atorvastatin at Parke-Davis that occurred during drug discovery was racemic followed by chiral chromatographic separation of the enantiomers. An early enantioselective route to atorvastatin made use of an ester chiral auxiliary to set the stereochemistry of the first of the two alcohol functional groups via a diastereoselective aldol reaction.[101][102]

Once the compound entered pre-clinical development, process chemistry developed a cost-effective and scalable synthesis.[101] In atorvastatin's case, a key element of the overall synthesis was ensuring stereochemical purity in the final drug substance, and hence establishing the first stereocenter became a key aspect of the overall design. The final commercial production of atorvastatin relied on a chiral pool approach, where the stereochemistry of the first alcohol functional group was carried into the synthesis—through the choice of isoascorbic acid, an inexpensive and easily sourced plant-derived natural product.[101][103]

The atorvastatin calcium complex involves two atorvastatin ions, one calcium ion and three water molecules.[104]

History

Bruce Roth, who was hired by Warner-Lambert as a chemist in 1982, had synthesized an "experimental compound" codenamed CI 981 – later called atorvastatin.[105][106] It was first made in August 1985.[101][105][107][108][109] Warner-Lambert management was concerned that atorvastatin was a me-too version of rival Merck & Co.'s orphan drug lovastatin (brand name Mevacor). Mevacor, which was first marketed in 1987, was the industry's first statin and Merck's synthetic version – simvastatin – was in the advanced stages of development.[106] Nevertheless, Bruce Roth and his bosses, Roger Newton and Ronald Cresswell, in 1985, convinced company executives to move the compound into expensive clinical trials. Early results comparing atorvastatin to simvastatin demonstrated that atorvastatin appeared more potent and with fewer side effects.[106]

In 1994, the findings of a Merck-funded study were published in The Lancet concluding the efficacy of statins in lowering cholesterol proving for the first time not only that a "statin reduced 'bad' LDL cholesterol but also that it led to a sharp drop in fatal heart attacks among people with heart disease."[106][110]

In 1996, Warner-Lambert entered into a co-marketing agreement with Pfizer to sell Lipitor, and in 2000, Pfizer acquired Warner-Lambert for $90.2 billion.[111][101][107][108] Lipitor was on the market by 1996.[109][112] By 2003, Lipitor had become the best selling pharmaceutical in the United States.[105] From 1996 to 2012, under the trade name Lipitor, atorvastatin became the world's best-selling medication of all time, with more than $125 billion in sales over approximately 14.5 years.[113] and $13 billion a year at its peak,[114] Lipitor alone "provided up to a quarter of Pfizer Inc.'s annual revenue for years."[113]

Pfizer's patent on atorvastatin expired in November 2011.[115]

Society and culture

Economics

Atorvastatin is relatively inexpensive.[6] Under provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in the United States, health plans may cover the costs of atorvastatin 10 mg and 20 mg for adults aged 40–75 years based on United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations.[116][117][118] Some plans only cover other statins.[119][120]

Brand names

Atorvastatin calcium tablets are sold under the brand name Lipitor.[121] Pfizer also packages the medication in combination with other medications, such as atorvastatin/amlodipine.[122]

Pfizer's U.S. patent on Lipitor expired on 30 November 2011.[123] Initially, generic atorvastatin was manufactured only by Watson Pharmaceuticals and India's Ranbaxy Laboratories. Prices for the generic version did not drop to the level of other generics—$10 or less for a month's supply—until other manufacturers began to supply the medication in May 2012.[124]

In other countries, atorvastatin calcium is made in tablet form by generic medication makers under various brand names including Atoris, Atorlip, Atorva, Atorvastatin Teva, Atorvastatina Parke-Davis, Avas, Cardyl, Liprimar, Litorva, Mactor, Orbeos, Prevencor, Sortis, Stator, Tahor, Torid, Torvacard, Torvast, Totalip, Tulip, Xarator, and Zarator.[125][126] Pfizer also makes its own generic version under the name Zarator.[127]

Medication recalls

On 9 November 2012, Indian drugmaker Ranbaxy Laboratories Ltd. voluntarily recalled 10-, 20- and 40-mg doses of its generic version of atorvastatin in the United States.[128][129][130] The lots of atorvastatin, packaged in bottles of 90 and 500 tablets, were recalled due to possible contamination with very small glass particles similar to the size of a grain of sand (less than 1 mm in size). The FDA received no reports of injury from the contamination.[128] Ranbaxy also issued recalls of bottles of 10-milligram tablets in August 2012 and March 2014, due to concerns that the bottles might contain larger, 20-milligram tablets and thus cause potential dosing errors.[131][132]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Atorvastatin (Lipitor) Use During Pregnancy". 3 February 2020. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/atorvastatin.html.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 "Lipitor- atorvastatin calcium tablet, film coated". https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=c6e131fe-e7df-4876-83f7-9156fc4e8228.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "Atorvastatin Calcium Monograph for Professionals". AHFS. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/atorvastatin-calcium.html.

- ↑ Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. 2006. p. 473. ISBN 9783527607495. https://books.google.com/books?id=FjKfqkaKkAAC&pg=PA473. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Top 100 Drugs e-book: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7020-5515-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=oeYjAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA197. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2021". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin - Drug Usage Statistics". https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Atorvastatin.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin Calcium". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/atorvastatin-calcium.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Efficacy and safety of atorvastatin in children and adolescents with familial hypercholesterolemia or severe hyperlipidemia: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial". The Journal of Pediatrics 143 (1): 74–80. July 2003. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00186-0. PMID 12915827.

- ↑ "Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial". JAMA 295 (13): 1556–65. April 2006. doi:10.1001/jama.295.13.jpc60002. PMID 16533939.

- ↑ "Reduction of LDL cholesterol by 25% to 60% in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia by atorvastatin, a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 15 (5): 678–82. May 1995. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.15.5.678. PMID 7749881.

- ↑ "Efficacy and safety of a new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, in patients with hypertriglyceridemia". JAMA 275 (2): 128–33. January 1996. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03530260042029. PMID 8531308.

- ↑ "The anti-atherosclerotic effects of lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia". Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis 13 (4): 216–9. August 2006. doi:10.5551/jat.13.216. PMID 16908955.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin: an effective lipid-modifying agent in familial hypercholesterolemia". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 17 (8): 1527–31. August 1997. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.17.8.1527. PMID 9301631.

- ↑ Australian medicines handbook 2006. Adelaide, S. Aust: Australian Medicines Handbook Pty Ltd.. 2006. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Prevention of coronary and stroke events with atorvastatin in hypertensive patients who have average or lower-than-average cholesterol concentrations, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial—Lipid Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial". Lancet 361 (9364): 1149–58. April 2003. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12948-0. PMID 12686036.

- ↑ "Quantifying effect of statins on low density lipoprotein cholesterol, ischaemic heart disease, and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 326 (7404): 1423–0. June 2003. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1423. PMID 12829554.

- ↑ "Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories". Circulation 97 (18): 1837–47. May 1998. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.97.18.1837. PMID 9603539.

- ↑ "Comparative dose efficacy study of atorvastatin versus simvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin, and fluvastatin in patients with hypercholesterolemia (the CURVES study)". The American Journal of Cardiology 81 (5): 582–7. March 1998. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00965-X. PMID 9514454.

- ↑ "Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with atorvastatin in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS): multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet 364 (9435): 685–96. 2004. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16895-5. PMID 15325833.

- ↑ "Analysis of efficacy and safety in patients aged 65–75 years at randomization: Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS)". Diabetes Care 29 (11): 2378–84. November 2006. doi:10.2337/dc06-0872. PMID 17065671.

- ↑ "Comparative efficacy study of atorvastatin vs simvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin and placebo in type 2 diabetic patients with hypercholesterolaemia". Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 2 (6): 355–62. December 2000. doi:10.1046/j.1463-1326.2000.00106.x. PMID 11225965.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Impact of statin therapy on coronary plaque composition: a systematic review and meta-analysis of virtual histology intravascular ultrasound studies". BMC Medicine 13 (1): 229. September 2015. doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0459-4. PMID 26385210.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease". The New England Journal of Medicine 365 (22): 2078–87. December 2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110874. PMID 22085316.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 "Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA 291 (9): 1071–80. March 2004. doi:10.1001/jama.291.9.1071. PMID 14996776.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Effect of Statins on Kidney Disease Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". American Journal of Kidney Diseases 67 (6): 881–892. June 2016. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.01.016. PMID 26905361.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Meta-analysis of the effect of statins on renal function". The American Journal of Cardiology 114 (4): 562–570. August 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.05.033. PMID 25001155.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Effect of high-dose atorvastatin on renal function in subjects with stroke or transient ischemic attack in the SPARCL trial". Stroke 45 (10): 2974–2982. October 2014. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005832. PMID 25147328.

- ↑ "Preoperative Statin Treatment for the Prevention of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients Undergoing Cardiac Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials". Heart, Lung & Circulation 26 (11): 1200–1207. November 2017. doi:10.1016/j.hlc.2016.11.024. PMID 28242291.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Comparative Efficacy of Statins for Prevention of Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Network Meta-Analysis". Angiology 70 (4): 305–316. April 2019. doi:10.1177/0003319718801246. PMID 30261736.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Comparative efficacy of pharmacological interventions for contrast-induced nephropathy prevention after coronary angiography: a network meta-analysis from randomized trials". International Urology and Nephrology 50 (6): 1085–1095. June 2018. doi:10.1007/s11255-018-1814-0. PMID 29404930. http://www.ijcem.com/files/ijcem0015476.pdf. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Beneficial effect of statin on preventing contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with renal insufficiency: A meta-analysis". Medicine 99 (10): e19473. March 2020. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000019473. PMID 32150109.

- ↑ "Meta-analysis of rosuvastatin efficacy in prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury". Drug Design, Development and Therapy 12: 3685–3690. October 2018. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S178020. PMID 30464400.

- ↑ "Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomised controlled trial". Lancet 366 (9500): 1849–1861. November 2005. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67667-2. PMID 16310551.

- ↑ "Effects of combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus". The New England Journal of Medicine 362 (17): 1563–1574. April 2010. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001282. PMID 20228404.

- ↑ ((Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) )) (May 2001). "Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP)". JAMA 285 (19): 2486–2497. doi:10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. PMID 11368702.

- ↑ "Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines". Circulation 110 (2): 227–239. July 2004. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. PMID 15249516.

- ↑ "Timing of statin dose: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 29 (14): e319–e322. October 2022. doi:10.1093/eurjpc/zwac085. PMID 35512427.

- ↑ "Effects of morning vs evening statin administration on lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Lipidology 11 (4): 972–985.e9. July 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2017.06.001. PMID 28826569. https://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/6701/1/Morning%20v%20Evening%20Statins%20Accepted%20Manuscript.pdf. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin and its metabolites after single and multiple dosing in hypercholesterolaemic haemodialysis patients". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 18 (5): 967–976. May 2003. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfg048. PMID 12686673.

- ↑ "Renal dysfunction does not alter the pharmacokinetics or LDL-cholesterol reduction of atorvastatin". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 37 (9): 816–819. September 1997. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb05629.x. PMID 9549635.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus undergoing hemodialysis". The New England Journal of Medicine 353 (3): 238–48. July 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043545. PMID 16034009.

- ↑ "Rosuvastatin and cardiovascular events in patients undergoing hemodialysis". The New England Journal of Medicine 360 (14): 1395–407. April 2009. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810177. PMID 19332456.

- ↑ "Statins and All-Cause Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis". Journal of the American Heart Association 9 (5): e014840. March 2020. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.014840. PMID 32089045.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients on hemodialysis". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 6 (6): 1316–25. June 2011. doi:10.2215/CJN.09121010. PMID 21493741.

- ↑ "The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial". Lancet 377 (9784): 2181–92. June 2011. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60739-3. PMID 21663949.

- ↑ "Statin Use and Risk of Cirrhosis and Related Complications in Patients With Chronic Liver Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 15 (10): 1521–1530.e8. October 2017. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.04.039. PMID 28479502.

- ↑ "Perinatal Outcomes After Statin Exposure During Pregnancy". JAMA Network Open 4 (12): e2141321. December 2021. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.41321. PMID 34967881.

- ↑ "TOXNET". U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search2/f?.%2Ftemp%2F~r09l0q%3A1.

- ↑ "Exposure of atorvastatin is unchanged but lactone and acid metabolites are increased several-fold in patients with atorvastatin-induced myopathy". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 79 (6): 532–9. June 2006. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.02.014. PMID 16765141. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/10852/28920/1/Artikkelxatorvabelastningxjunix2006xLipidklinikken.pdf. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic drug interactions with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 41 (5): 343–70. 2002. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241050-00003. PMID 12036392.

- ↑ "Statin use and the risk of developing diabetes: a network meta-analysis". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety (Wiley) 25 (10): 1131–1149. October 2016. doi:10.1002/pds.4020. PMID 27277934.

- ↑ "Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials". Lancet (Elsevier BV) 375 (9716): 735–742. February 2010. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61965-6. PMID 20167359.

- ↑ "Statins and risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus". Circulation 126 (18): e282–e284. October 2012. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.122135. PMID 23109518.

- ↑ "Predictors of new-onset diabetes in patients treated with atorvastatin: results from 3 large randomized clinical trials". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 57 (14): 1535–1545. April 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.047. PMID 21453832.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials". Lancet 376 (9753): 1670–1681. November 2010. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. PMID 21067804.

- ↑ "Effect of statin therapy on muscle symptoms: an individual participant data meta-analysis of large-scale, randomised, double-blind trials". Lancet 400 (10355): 832–845. September 2022. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01545-8. PMID 36049498.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 "Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease". The New England Journal of Medicine 352 (14): 1425–1435. April 2005. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa050461. PMID 15755765.

- ↑ "Unintended effects of statins from observational studies in the general population: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Medicine 12 (1): 51. March 2014. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-12-51. PMID 24655568.

- ↑ "Statin-induced rhabdomyolysis: a comprehensive review of case reports". Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada 66 (2): 124–132. April 2014. doi:10.3138/ptc.2012-65. PMID 24799748.

- ↑ "Risks associated with statin therapy: a systematic overview of randomized clinical trials". Circulation 114 (25): 2788–97. December 2006. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624890. PMID 17159064.

- ↑ "Safety of atorvastatin derived from analysis of 44 completed trials in 9,416 patients". American Journal of Cardiology 92 (6): 670–6. September 2003. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00820-8. PMID 12972104.

- ↑ "Effect of statins on fasting plasma glucose in diabetic and nondiabetic patients". Journal of Investigative Medicine 57 (3): 495–499. March 2009. doi:10.2310/JIM.0b013e318197ec8b. PMID 19188844.

- ↑ "Statin therapy on glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients: A network meta-analysis". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics 43 (4): 556–570. August 2018. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12690. PMID 29733433.

- ↑ "Effect of atorvastatin on glycaemia progression in patients with diabetes: an analysis from the Collaborative Atorvastatin in Diabetes Trial (CARDS)". Diabetologia 59 (2): 299–306. February 2016. doi:10.1007/s00125-015-3802-6. PMID 26577796.

- ↑ "Do statins impair cognition? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of General Internal Medicine 30 (3): 348–58. March 2015. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-3115-3. PMID 25575908.

- ↑ "Use of statins and the risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Scientific Reports 8 (1): 5804. April 2018. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-24248-8. PMID 29643479. Bibcode: 2018NatSR...8.5804C.

- ↑ "Effects of Statins on Memory, Cognition, and Brain Volume in the Elderly". Journal of the American College of Cardiology 74 (21): 2554–2568. November 2019. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.041. PMID 31753200.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin: A medicine used to lower cholesterol". 3 January 2019. https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/atorvastatin/.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin Use Associated With Acute Pancreatitis: A Case-Control Study in Taiwan" (in en-US). Medicine 95 (7): e2545. February 2016. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000002545. PMID 26886597.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "Lipid-modifying therapies and risk of pancreatitis: a meta-analysis". JAMA 308 (8): 804–811. August 2012. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.8439. PMID 22910758. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/69063/3/69063.pdf. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ "The effect of statins on erectile dysfunction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (7): 1626–35. July 2014. doi:10.1111/jsm.12521. PMID 24684744.

- ↑ "The effect of statins on erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Journal of Sexual Medicine 11 (6): 1367–75. June 2014. doi:10.1111/jsm.12497. PMID 24628781.

- ↑ "Incidence of hospitalized rhabdomyolysis in patients treated with lipid-lowering drugs". JAMA 292 (21): 2585–2590. December 2004. doi:10.1001/jama.292.21.2585. PMID 15572716.

- ↑ "Long-term safety of pravastatin-gemfibrozil therapy in mixed hyperlipidemia". Clinical Cardiology 22 (1): 25–28. January 1999. doi:10.1002/clc.4960220110. PMID 9929751.

- ↑ "Statin-fibrate combination therapy". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 35 (7–8): 908–917. July 2001. doi:10.1345/aph.10315. PMID 11485144.

- ↑ "Independent, reliable, relevant and respected" (in en-AU). https://www.tg.org.au/.

- ↑ "Adverse events following statin-fenofibrate therapy versus statin alone: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology 40 (3): 219–226. March 2013. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12053. PMID 23324122.

- ↑ "Efficacy of atorvastatin and gemfibrozil, alone and in low dose combination, in the treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 88 (7): 3212–3217. July 2003. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030153. PMID 12843167.

- ↑ "Itraconazole alters the pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin to a greater extent than either cerivastatin or pravastatin". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 68 (4): 391–400. October 2000. doi:10.1067/mcp.2000.110537. PMID 11061579.

- ↑ "Drug interactions with lipid-lowering drugs: mechanisms and clinical relevance". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 80 (6): 565–81. December 2006. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.09.003. PMID 17178259.

- ↑ "Rifampin markedly decreases and gemfibrozil increases the plasma concentrations of atorvastatin and its metabolites". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 78 (2): 154–67. August 2005. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2005.04.007. PMID 16084850.

- ↑ "Efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin in treatment of dyslipidemia". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 62 (10): 1033–47. May 2005. doi:10.1093/ajhp/62.10.1033. PMID 15901588.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Recommendations for Management of Clinically Significant Drug-Drug Interactions With Statins and Select Agents Used in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation 134 (21): e468–e495. November 2016. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000456. PMID 27754879.

- ↑ "Effects of vitamin D supplementation in atorvastatin-treated patients: a new drug interaction with an unexpected consequence". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 85 (2): 198–203. February 2009. doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.165. PMID 18754003.

- ↑ "Drug-grapefruit juice interactions". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 75 (9): 933–42. September 2000. doi:10.4065/75.9.933. PMID 10994829.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "Effects of grapefruit juice on the pharmacokinetics of pitavastatin and atorvastatin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 60 (5): 494–7. November 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02462.x. PMID 16236039.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Serum concentrations and clinical effects of atorvastatin in patients taking grapefruit juice daily". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 72 (3): 434–41. September 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03996.x. PMID 21501216.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "Grapefruit juice increases serum concentrations of atorvastatin and has no effect on pravastatin". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 66 (2): 118–27. August 1999. doi:10.1053/cp.1999.v66.100453001. PMID 10460065.

- ↑ "Meals and medicines". Australian Prescriber 29 (2): 40–42. 1 April 2006. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2006.026. https://www.nps.org.au/australian-prescriber/magazine/29/2/40/2. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "Statins reduce vascular inflammation in atherogenesis: A review of underlying molecular mechanisms". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 122: 105735. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2020.105735. PMID 32126319.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Update on the efficacy of statin treatment in acute coronary syndromes". European Journal of Clinical Investigation 44 (5): 501–515. May 2014. doi:10.1111/eci.12255. PMID 24601937.

- ↑ "High-dose statins should only be used in atherosclerotic strokes". Stroke 43 (7): 1994–1995. July 2012. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.633339. PMID 22581818.

- ↑ "High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack". The New England Journal of Medicine 355 (6): 549–559. August 2006. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061894. PMID 16899775.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin: its clinical role in cerebrovascular prevention". Drugs 67 (1): 55–62. 1 November 2007. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767001-00006. PMID 17910521.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin for lowering lipids". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015 (3): CD008226. March 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008226.pub3. PMID 25760954.

- ↑ "Genetic factors affecting statin concentrations and subsequent myopathy: a HuGENet systematic review". Genetics in Medicine 16 (11): 810–819. November 2014. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.41. PMID 24810685.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 99.4 99.5 99.6 "Genome-wide association study of genetic determinants of LDL-c response to atorvastatin therapy: importance of Lp(a)". Journal of Lipid Research 53 (5): 1000–11. May 2012. doi:10.1194/jlr.P021113. PMID 22368281.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 100.3 "An association study of 43 SNPs in 16 candidate genes with atorvastatin response". Pharmacogenomics Journal 5 (6): 352–8. 2005. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500328. PMID 16103896.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 101.3 101.4 "1 the Discovery and Development of Atorvastatin, A Potent Novel Hypolipidemic Agent". The discovery and development of atorvastatin, a potent novel hypolipidemic agent. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. 40. Elsevier. 2002. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70080-8. ISBN 978-0-444-51054-9.

- ↑ "Inhibitors of Cholesterol Biosynthesis. 3. Tetrahydro-4-hydroxy-6-[2-(1H-pyrrol-1-yl)ethyl]-2H-pyran 2-one Inhibitors of HMG-CoA Reductase. 2. Effects of Introducing Substituents at Positions Three and Four of the Pyrrole Nucleus". J. Med. Chem. 34 (1): 357–366. 1991. doi:10.1021/jm00105a056. PMID 1992137.

- ↑ "Chapter 9. Atorvastatin Calcium (Lipitor)". Contemporary Drug Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. 2004. pp. 113–125. ISBN 978-0-471-21480-9.

- ↑ "Fig. 1. Chemical structure of Atorvastatin Calcium". https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Chemical-structure-of-Atorvastatin-Calcium_fig1_317526111.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 105.2 "The $10 Billion Pill Hold the fries, please. Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering medication, has become the bestselling pharmaceutical in history. Here's how Pfizer did it". Fortune. 20 January 2003. https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/01/20/335643/index.htm.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 106.3 "The fall of the world's best-selling drug". Financial Times. 28 November 2009. https://www.ft.com/content/d0f7af5c-d7e6-11de-b578-00144feabdc0.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Roth BD, "Trans-6-[2-(3- or 4-carboxamido-substituted pyrrol-1-yl)alkyl]-4-hydroxypyran-2-one inhibitors of cholesterol synthesis", US patent 4681893, issued 21 July 1987

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 "The Early History of Parke-Davis and Company". Bull. Hist. Chem. 25 (1): 28–34. 2000. https://www.scs.illinois.edu/~mainzv/HIST/bulletin_open_access/v25-1/v25-1%20p28-34.pdf. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 "Pfizer Gets Its Deal to Buy Warner-Lambert for $90.2 Billion". The New York Times. 8 February 2000. https://www.nytimes.com/2000/02/08/business/pfizer-gets-its-deal-to-buy-warner-lambert-for-90.2-billion.html.

- ↑ "The Birth of a Blockbuster: Lipitor's Route out of the Lab". The Wall Street Journal. 24 January 2000. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB948677773420632448.

- ↑ "Approval Letter". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/pre96/020702_s000.pdf.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 "Lipitor becomes world's top-selling drug". Crain's New York Business via Associated Press. 28 December 2011. https://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20111228/HEALTH_CARE/111229902/lipitor-becomes-world-s-top-selling-drug.

- ↑ "The Vindication of Roger Newton". Ann Arbor Observer. April 2020. https://annarborobserver.com/articles/the_vindication_of_roger_newton.html#.YfvQI_nMKUk.

- ↑ "Lipitor loses patent, goes generic". CNN. 30 November 2011. https://edition.cnn.com/2011/11/30/health/lipitor-generic/index.html.

- ↑ "PPACA no cost-share preventive medications". Cigna. https://www.cigna.com/assets/docs/about-cigna/no-cost-share-preventive-medications.pdf.

- ↑ "Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Recommendation Statement". American Family Physician 95 (2). 15 January 2017. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0115/od1.html. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ↑ "Recommendation: Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Preventive Medication". 15 November 2016. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/statin-use-in-adults-preventive-medication.

- ↑ "SignatureValue Zero Cost Share Preventive Medications PDL". September 2021. https://www.uhc.com/content/dam/uhcdotcom/en/Pharmacy/PDFs/UHC-SignatureValue-Formulary-PPACA-ZeroCost-Preventive-Meds-Eff-Sept-2021.pdf.

- ↑ "Affordable Care Act Implementation FAQs - Set 12". 22 April 2013. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Fact-Sheets-and-FAQs/aca_implementation_faqs12.

- ↑ Medical Product Reviews. "Atorvastatin Calcium (Lipitor Tablets) – Uses, Dosage and Side Effects". http://www.medicalproductreviews.com/atorvastatin-calcium-lipitor.html.

- ↑ News Medical (March 2010). "Lipitor – What is Lipitor?". http://www.news-medical.net/health/Lipitor-What-is-Lipitor.aspx.

- ↑ "Pfizer's 180-Day War for Lipitor". 8 August 2013. https://www.pm360online.com/pfizers-180-day-war-for-lipitor/.

- ↑ "Price to UK for 28 tablets from £3.25 (10mg) to £10.00 (80mg)". National Health Service. June 2012. http://www.nelm.nhs.uk/en/NeLM-Area/News/2012---May/30/June-Drug-Tariff-Reduced-prices-for-atorvastatin/.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin international". 4 May 2020. https://www.drugs.com/international/atorvastatin.html.

- ↑ "Lipitor referral". 17 September 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/lipitor.

- ↑ "Atorvastatin sole funding announced". PharmacyToday.co.nz. 31 May 2012. http://www.pharmacytoday.co.nz/news/2012/may-2012/31/atorvastatin-sole-funding-announced.aspx.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 "FDA Statement on Ranbaxy Atorvastatin Recall". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 December 2012. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm329951.htm.

- ↑ "Ranbaxy Recalls Generic Lipitor Doses". The Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2012. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324352004578137241552301304.

- ↑ "Ranbaxy recalls generic Lipitor doses". The Boston Globe. Associated Press. 24 November 2012. https://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2012/11/24/ranbaxy-recalls-generic-lipitor-doses/iRsoUYfYzHStRzIe82LFCK/story.html.

- ↑ "Ranbaxy Recalls More Than 64,000 Bottles of Generic Lipitor in U.S.". The Wall Street Journal. 7 March 2014. https://www.wsj.com/articles/ranbaxy-recalls-more-than-64-000-bottles-of-generic-lipitor-in-u-s-1394226119.

- ↑ "Indian drugmaker Ranbaxy recalls more than 64,000 bottles of its generic version of Lipitor". The Washington Post. 8 March 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/indian-drugmaker-ranbaxy-recalls-more-than-64000-bottles-of-its-generic-version-of-lipitor/2014/03/08/e36a41b4-a716-11e3-a5fa-55f0c77bf39c_story.html.

Further reading

- "Best-selling human medicines 2002–2004". Drug Discovery Today 10 (11): 739–42. June 2005. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03468-9. PMID 15922927.

- "The $10 Billion Pill Hold the fries, please. Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering medication, has become the bestselling pharmaceutical in history. Here's how Pfizer did it". Fortune. 20 January 2003. https://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/01/20/335643/index.htm.

- "The Birth of a Blockbuster: Lipitor's Route out of the Lab". The Wall Street Journal. 24 January 2000. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB948677773420632448.

|