Chemistry:Tin(II) oxide

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Tin(II) oxide

| |

| Other names

Stannous oxide

Tin monoxide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| SnO | |

| Molar mass | 134.709 g/mol |

| Appearance | black or red powder when anhydrous, white when hydrated |

| Density | 6.45 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 1,080 °C (1,980 °F; 1,350 K)[1] |

| insoluble | |

| −19.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| tetragonal | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar

entropy (S |

56 J·mol−1·K−1[2] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−285 kJ·mol−1[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0956 |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

none[3] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 2 mg/m3[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D.[3] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Tin sulfide Tin selenide Tin telluride |

Other cations

|

Carbon monoxide Silicon monoxide Germanium(II) oxide Lead(II) oxide |

| Tin dioxide | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Tin(II) oxide (stannous oxide) is a compound with the formula SnO. It is composed of tin and oxygen where tin has the oxidation state of +2. There are two forms, a stable blue-black form and a metastable red form.

Preparation and reactions

Blue-black SnO can be produced by heating the tin(II) oxide hydrate, SnO·xH2O (x<1) precipitated when a tin(II) salt is reacted with an alkali hydroxide such as NaOH.[4]

Metastable, red SnO can be prepared by gentle heating of the precipitate produced by the action of aqueous ammonia on a tin(II) salt.[4]

SnO may be prepared as a pure substance in the laboratory, by controlled heating of tin(II) oxalate (stannous oxalate) in the absence of air or under a CO2 atmosphere. This method is also applied to the production of ferrous oxide and manganous oxide.[5][6]

- SnC2O4·2H2O → SnO + CO2 + CO + 2 H2O

Tin(II) oxide burns in air with a dim green flame to form SnO2.[4]

- 2 SnO + O2 → 2 SnO2

When heated in an inert atmosphere initially disproportionation occurs giving Sn metal and Sn3O4 which further reacts to give SnO2 and Sn metal.[4]

- 4SnO → Sn3O4 + Sn

- Sn3O4 → 2SnO2 + Sn

SnO is amphoteric, dissolving in strong acid to give tin(II) salts and in strong base to give stannites containing Sn(OH)3−.[4] It can be dissolved in strong acid solutions to give the ionic complexes Sn(OH2)32+ and Sn(OH)(OH2)2+, and in less acid solutions to give Sn3(OH)42+.[4] Note that anhydrous stannites, e.g. K2Sn2O3, K2SnO2 are also known.[7][8][9] SnO is a reducing agent and is thought to reduce copper(I) to metallic clusters in the manufacture of so-called "copper ruby glass".[10]

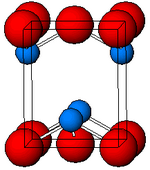

Structure

Black, α-SnO adopts the tetragonal PbO layer structure containing four coordinate square pyramidal tin atoms.[11] This form is found in nature as the rare mineral romarchite.[12] The asymmetry is usually simply ascribed to a sterically active lone pair; however, electron density calculations show that the asymmetry is caused by an antibonding interaction of the Sn(5s) and the O(2p) orbitals.[13] The electronic structure and chemistry of the lone pair determines most of the properties of the material.[14]

Non-stoichiometry has been observed in SnO.[15]

The electronic band gap has been measured between 2.5eV and 3eV.[16]

Uses

The dominant use of stannous oxide is as a precursor in manufacturing of other, typically divalent, tin compounds or salts. Stannous oxide may also be employed as a reducing agent and in the creation of ruby glass.[17] It has a minor use as an esterification catalyst.

Cerium(III) oxide in ceramic form, together with Tin(II) oxide (SnO) is used for illumination with UV light.[18]

References

- ↑ Tin and Inorganic Tin Compounds: Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 65, (2005), World Health Organization

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed.. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0615". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/npg/npgd0615.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Egon Wiberg, Arnold Frederick Holleman (2001) Inorganic Chemistry, Elsevier ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ↑ Satya Prakash (2000),Advanced Inorganic Chemistry: V. 1, S. Chand, ISBN 81-219-0263-0

- ↑ Arthur Sutcliffe (1930) Practical Chemistry for Advanced Students (1949 Ed.), John Murray - London.

- ↑ Braun, Rolf Michael; Hoppe, Rudolf (1978). "The First Oxostannate(II): K2Sn2O3". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 17 (6): 449–450. doi:10.1002/anie.197804491.

- ↑ Braun, R. M.; Hoppe, R. (1982). "Über Oxostannate(II). III. K2Sn2O3, Rb2Sn2O3 und Cs2Sn2O3 - ein Vergleich". Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie 485: 15–22. doi:10.1002/zaac.19824850103.

- ↑ R M Braun R Hoppe Z. Naturforsch. (1982), 37B, 688-694

- ↑ Bring, T.; Jonson, B.; Kloo, L.; Rosdahl, J; Wallenberg, R. (2007), "Colour development in copper ruby alkali silicate glasses. Part I: The impact of tin oxide, time and temperature", Glass Technology, Eur. J. Glass Science & Technology, Part A 48 (2): 101–108, ISSN 1753-3546

- ↑ Wells A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry 5th edition Oxford Science Publications ISBN 0-19-855370-6

- ↑ Ramik, R. A.; Organ, R. M.; Mandarino, J. A. (2003). "On Type Romarchite and Hydroromarchite from Boundary Falls, Ontario, and Notes on Other Occurrences". The Canadian Mineralogist 41 (3): 649–657. doi:10.2113/gscanmin.41.3.649.

- ↑ Walsh, Aron; Watson, Graeme W. (2004). "Electronic structures of rocksalt, litharge, and herzenbergite SnO by density functional theory". Physical Review B 70 (23): 235114. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.235114. Bibcode: 2004PhRvB..70w5114W.

- ↑ Mei, Antonio B.; Miao, Ludi; Wahila, Matthew J.; Khalsa, Guru; Wang, Zhe; Barone, Matthew; Schreiber, Nathaniel J.; Noskin, Lindsey E. et al. (2019-10-21). "Adsorption-controlled growth and properties of epitaxial SnO films". Physical Review Materials 3 (10): 105202. doi:10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.3.105202. Bibcode: 2019PhRvM...3j5202M. https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevMaterials.3.105202.

- ↑ Moreno, M. S.; Varela, A.; Otero-Díaz, L. C. (1997). "Cation nonstoichiometry in tin-monoxide-phaseSn1−δOwith tweed microstructure". Physical Review B 56 (9): 5186–5192. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.56.5186.

- ↑ Science and Technology of Chemiresistor Gas Sensors By Dinesh K. Aswal, Shiv K. Gupta (2006), Nova Publishers, ISBN 1-60021-514-9

- ↑ "Red Glass Coloration - A Colorimetric and Structural Study" By Torun Bring. Pub. Vaxjo University.

- ↑ Peplinski, D.R.; Wozniak, W.T.; Moser, J.B. (1980). "Spectral Studies of New Luminophors for Dental Porcelain". Journal of Dental Research (Jdr.iadrjournals.org) 59 (9): 1501–1506. doi:10.1177/00220345800590090801. PMID 6931128. http://jdr.iadrjournals.org/cgi/reprint/59/9/1501.pdf. Retrieved 2012-04-05.[no|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

|