Dedekind number

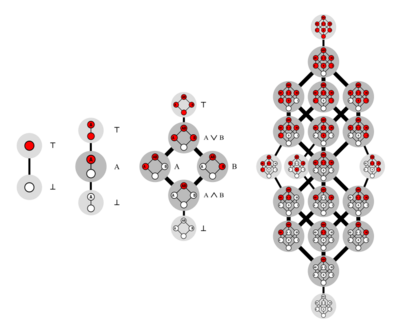

The free distributive lattices of monotonic Boolean functions on 0, 1, 2, and 3 arguments, with 2, 3, 6, and 20 elements respectively (move mouse over right diagram to see description)

The free distributive lattices of monotonic Boolean functions on 0, 1, 2, and 3 arguments, with 2, 3, 6, and 20 elements respectively (move mouse over right diagram to see description)In mathematics, the Dedekind numbers are a rapidly growing sequence of integers named after Richard Dedekind, who defined them in 1897. The Dedekind number M(n) is the number of monotone boolean functions of n variables. Equivalently, it is the number of antichains of subsets of an n-element set, the number of elements in a free distributive lattice with n generators, and one more than the number of abstract simplicial complexes on a set with n elements.

Accurate asymptotic estimates of M(n) and an exact expression as a summation are known.[1] However Dedekind's problem of computing the values of M(n) remains difficult: no closed-form expression for M(n) is known, and exact values of M(n) have been found only for n ≤ 9 (sequence A000372 in the OEIS).

Definitions

A Boolean function is a function that takes as input n Boolean variables (that is, values that can be either false or true, or equivalently binary values that can be either 0 or 1), and produces as output another Boolean variable. It is monotonic if, for every combination of inputs, switching one of the inputs from false to true can only cause the output to switch from false to true and not from true to false. The Dedekind number M(n) is the number of different monotonic Boolean functions on n variables.[2]

An antichain of sets (also known as a Sperner family) is a family of sets, none of which is contained in any other set. If V is a set of n Boolean variables, an antichain A of subsets of V defines a monotone Boolean function f, where the value of f is true for a given set of inputs if some subset of the true inputs to f belongs to A and false otherwise. Conversely every monotone Boolean function defines in this way an antichain, of the minimal subsets of Boolean variables that can force the function value to be true. Therefore, the Dedekind number M(n) equals the number of different antichains of subsets of an n-element set.[3]

A third, equivalent way of describing the same class of objects uses lattice theory. From any two monotone Boolean functions f and g we can find two other monotone Boolean functions f ∧ g and f ∨ g, their logical conjunction and logical disjunction respectively. The family of all monotone Boolean functions on n inputs, together with these two operations, forms a distributive lattice, the lattice given by Birkhoff's representation theorem from the partially ordered set of subsets of the n variables with set inclusion as the partial order. This construction produces the free distributive lattice with n generators.[4] Thus, the Dedekind numbers count the elements in free distributive lattices.[5]

The Dedekind numbers also count one more than the number of abstract simplicial complexes on a set with n elements, families of sets with the property that any non-empty subset of a set in the family also belongs to the family. Any antichain (except {Ø}) determines a simplicial complex, the family of subsets of antichain members, and conversely the maximal simplices in a complex form an antichain.[6]

Example

For n = 2, there are six monotonic Boolean functions and six antichains of subsets of the two-element set {x,y}:

- The function f(x,y) = false that ignores its input values and always returns false corresponds to the empty antichain Ø.

- The logical conjunction f(x,y) = x ∧ y corresponds to the antichain { {x,y} } containing the single set {x,y}.

- The function f(x,y) = x that ignores its second argument and returns the first argument corresponds to the antichain { {x} } containing the single set {x}

- The function f(x,y) = y that ignores its first argument and returns the second argument corresponds to the antichain { {y} } containing the single set {y}

- The logical disjunction f(x,y) = x ∨ y corresponds to the antichain { {x}, {y} } containing the two sets {x} and {y}.

- The function f(x,y) = true that ignores its input values and always returns true corresponds to the antichain {Ø} containing only the empty set.[7]

Values

The exact values of the Dedekind numbers are known for 0 ≤ n ≤ 9:

- 2, 3, 6, 20, 168, 7581, 7828354, 2414682040998, 56130437228687557907788, 286386577668298411128469151667598498812366 (sequence A000372 in the OEIS).

The first five of these numbers (i.e., M(0) to M(4)) are given by (Dedekind 1897).[8] M(5) was calculated by (Church 1940). M(6) was calculated by (Ward 1946), M(7) was calculated by (Church 1965) and (Berman Köhler), M(8) by (Wiedemann 1991) and M(9) was simultaneously discovered in 2023 by Christian Jäkel[9][10] and Lennart Van Hirtum et al.[11]

If n is even, then M(n) must also be even.[12] The calculation of the fifth Dedekind number M(5) = 7581 disproved a conjecture by Garrett Birkhoff that M(n) is always divisible by (2n − 1)(2n − 2).[13]

Summation formula

(Kisielewicz 1988) rewrote the logical definition of antichains into the following arithmetic formula for the Dedekind numbers:

where is the th bit of the number , which can be written using the floor function as

However, this formula is not helpful for computing the values of M(n) for large n due to the large number of terms in the summation.[14]

Asymptotics

The logarithm of the Dedekind numbers can be estimated accurately via the bounds

Here the left inequality counts the antichains in which each set has exactly elements, and the right inequality was proven by (Kleitman Markowsky).

(Korshunov 1981) provided the even more accurate estimates[15]

for even n, and

for odd n, where

and

The main idea behind these estimates is that, in most antichains, all the sets have sizes that are very close to n/2.[15] For n = 2, 4, 6, 8 Korshunov's formula provides an estimate that is inaccurate by a factor of 9.8%, 10.2%, 4.1%, and −3.3%, respectively.[16]

Notes

- ↑ (Kleitman Markowsky); (Korshunov 1981); (Kahn 2002); (Kisielewicz 1988).

- ↑ Kisielewicz (1988).

- ↑ (Kahn 2002).

- ↑ The definition of free distributive lattices used here allows as lattice operations any finite meet and join, including the empty meet and empty join. For the free distributive lattice in which only pairwise meets and joins are allowed, one should eliminate the top and bottom lattice elements and subtract two from the Dedekind numbers.

- ↑ (Church 1940); (Church 1965); (Zaguia 1993).

- ↑ (Kisielewicz 1988).

- ↑ That this antichain corresponds to the top lattice element of the lattice can be seen by considering the definition of meet in the article on antichains.

- ↑ Tombak, Mati (2001). "On Logical Method for Counting Dedekind Numbers". Fundamentals of Computation Theory. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2138. pp. 424–427. doi:10.1007/3-540-44669-9_48. ISBN 978-3-540-42487-1.

- ↑ Jäkel, Christian (2023-04-03). "A computation of the ninth Dedekind Number". arXiv:2304.00895 [math.CO].

- ↑ Jäkel, Christian (2023). "A computation of the ninth Dedekind number". Journal of Computational Algebra 6-7. doi:10.1016/j.jaca.2023.100006.

- ↑ Van Hirtum, Lennart (2023-04-06). "A computation of D(9) using FPGA Supercomputing". arXiv:2304.03039 [cs.DM].

- ↑ (Yamamoto 1953).

- ↑ (Church 1940).

- ↑ For example, for , the summation contains terms, which is far beyond what can be numerically summed.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 (Zaguia 1993).

- ↑ Brown, K. S., Generating the monotone Boolean functions, https://www.mathpages.com/home/kmath094/kmath094.htm

References

- Berman, Joel; Köhler, Peter (1976), "Cardinalities of finite distributive lattices", Mitt. Math. Sem. Giessen 121: 103–124.

- Church, Randolph (1940), "Numerical analysis of certain free distributive structures", Duke Mathematical Journal 6 (3): 732–734, doi:10.1215/s0012-7094-40-00655-x.

- Church, Randolph (1965), "Enumeration by rank of the free distributive lattice with 7 generators", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 11: 724. As cited by (Wiedemann 1991).

- "Über Zerlegungen von Zahlen durch ihre größten gemeinsamen Teiler", Gesammelte Werke, 2, 1897, pp. 103–148.

- Kahn, Jeff (2002), "Entropy, independent sets and antichains: a new approach to Dedekind's problem", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 130 (2): 371–378, doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-01-06058-0.

- Kisielewicz, Andrzej (1988), "A solution of Dedekind's problem on the number of isotone Boolean functions", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 1988 (386): 139–144, doi:10.1515/crll.1988.386.139

- "On Dedekind's problem: the number of isotone Boolean functions. II", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 213: 373–390, 1975, doi:10.2307/1998052.

- Korshunov, A. D. (1981), "The number of monotone Boolean functions", Problemy Kibernet. 38: 5–108.

- Tombak, Mati (2001), "On Logical Method for Counting Dedekind Numbers", Fundamentals of Computation Theory, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2138, pp. 424–427, doi:10.1007/3-540-44669-9_48, ISBN 978-3-540-42487-1.

- "Note on the order of free distributive lattices", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 52: 423, 1946, doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1946-08568-7.

- Wiedemann, Doug (1991), "A computation of the eighth Dedekind number", Order 8 (1): 5–6, doi:10.1007/BF00385808.

- Yamamoto, Koichi (1953), "Note on the order of free distributive lattices", Science Reports of the Kanazawa University 2 (1): 5–6.

- Zaguia, Nejib (1993), "Isotone maps: enumeration and structure", in Sauer, N. W.; Woodrow, R. E.; Sands, B., Finite and Infinite Combinatorics in Sets and Logic (Proc. NATO Advanced Study Inst., Banff, Alberta, Canada, May 4, 1991), Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 421–430.

|