Abundant number

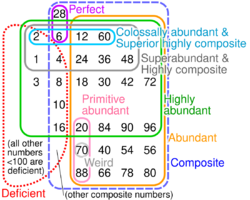

In number theory, an abundant number or excessive number is a positive integer for which the sum of its proper divisors is greater than the number. The integer 12 is the first abundant number. Its proper divisors are 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 for a total of 16. The amount by which the sum exceeds the number is the abundance. The number 12 has an abundance of 4, for example.

Definition

An abundant number is a natural number n for which the sum of divisors σ(n) satisfies σ(n) > 2n, or, equivalently, the sum of proper divisors (or aliquot sum) s(n) satisfies s(n) > n.

The abundance of a natural number is the integer σ(n) − 2n (equivalently, s(n) − n).

Examples

The first 28 abundant numbers are:

- 12, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 42, 48, 54, 56, 60, 66, 70, 72, 78, 80, 84, 88, 90, 96, 100, 102, 104, 108, 112, 114, 120, ... (sequence A005101 in the OEIS).

For example, the proper divisors of 24 are 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 12, whose sum is 36. Because 36 is greater than 24, the number 24 is abundant. Its abundance is 36 − 24 = 12.

Properties

- The smallest odd abundant number is 945.

- The smallest abundant number not divisible by 2 or by 3 is 5391411025 whose distinct prime factors are 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, and 29 (sequence A047802 in the OEIS). An algorithm given by Iannucci in 2005 shows how to find the smallest abundant number not divisible by the first k primes.[1] If represents the smallest abundant number not divisible by the first k primes then for all we have

- for sufficiently large k.

- Every multiple of a perfect number (except the perfect number itself) is abundant.[2] For example, every multiple of 6 greater than 6 is abundant because

- Every multiple of an abundant number is abundant.[2] For example, every multiple of 20 (including 20 itself) is abundant because

- Consequently, infinitely many even and odd abundant numbers exist.

- Furthermore, the set of abundant numbers has a non-zero natural density, which is known to lie between 0.2476171 and 0.2476475.[3][4][5]

- An abundant number which is not the multiple of an abundant number or perfect number (i.e. all its proper divisors are deficient) is called a primitive abundant number

- An abundant number whose abundance is greater than any lower number is called a highly abundant number, and one whose relative abundance (i.e. s(n)/n ) is greater than any lower number is called a superabundant number

- Every integer greater than 20161 can be written as the sum of two abundant numbers. The largest even number that is not the sum of two abundant numbers is 46.[6]

- An abundant number which is not a semiperfect number is called a weird number.[7] An abundant number with abundance 1 is called a quasiperfect number, although none have yet been found.

- Every abundant number is a multiple of either a perfect number or a primitive abundant number.

Related concepts

Numbers whose sum of proper factors equals the number itself (such as 6 and 28) are called perfect numbers, while numbers whose sum of proper factors is less than the number itself are called deficient numbers. The first known classification of numbers as deficient, perfect or abundant was by Nicomachus in his Introductio Arithmetica (circa 100 AD), which described abundant numbers as like deformed animals with too many limbs.

The abundancy index of n is the ratio σ(n)/n.[8] Distinct numbers n1, n2, ... (whether abundant or not) with the same abundancy index are called friendly numbers.

The sequence (ak) of least numbers n such that σ(n) > kn, in which a2 = 12 corresponds to the first abundant number, grows very quickly (sequence A134716 in the OEIS).

The smallest odd integer with abundancy index exceeding 3 is 1018976683725 = 33 × 52 × 72 × 11 × 13 × 17 × 19 × 23 × 29.[9]

If p = (p1, ..., pn) is a list of primes, then p is termed abundant if some integer composed only of primes in p is abundant. A necessary and sufficient condition for this is that the product of pi/(pi − 1) be > 2.[10]

References

- ↑ D. Iannucci (2005), "On the smallest abundant number not divisible by the first k primes", Bulletin of the Belgian Mathematical Society 12 (1): 39–44, doi:10.36045/bbms/1113318127, https://projecteuclid.org/journals/bulletin-of-the-belgian-mathematical-society-simon-stevin/volume-12/issue-1/On-the-smallest-abundant-number-not-divisible-by-the-first/10.36045/bbms/1113318127.full

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Tattersall (2005) p.134

- ↑ Hall, Richard R.; Tenenbaum, Gérald (1988). Divisors. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics. 90. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-521-34056-4.

- ↑ Deléglise, Marc (1998). "Bounds for the density of abundant integers". Experimental Mathematics 7 (2): 137–143. doi:10.1080/10586458.1998.10504363. ISSN 1058-6458. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.em/1048515661.

- ↑ Kobayashi, Mitsuo (2010), "On the density of abundant numbers", Dartmouth Dissertations: 1–239, doi:10.1349/ddlp.1662, http://collections.dartmouth.edu/archive/object/dcdis/dcdis-kobayashim2010

- ↑ Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A048242 (Numbers that are not the sum of two abundant numbers)". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A048242.

- ↑ Tattersall (2005) p.144

- ↑ Laatsch, Richard (1986). "Measuring the abundancy of integers". Mathematics Magazine 59 (2): 84–92. doi:10.2307/2690424. ISSN 0025-570X.

- ↑ For smallest odd integer k with abundancy index exceeding n, see Sloane, N. J. A., ed. "Sequence A119240 (Least odd number k such that sigma(k)/k >= n.)". OEIS Foundation. https://oeis.org/A119240.

- ↑ Friedman, Charles N. (1993). "Sums of divisors and Egyptian fractions". Journal of Number Theory 44 (3): 328–339. doi:10.1006/jnth.1993.1057.

- Tattersall, James J. (2005). Elementary Number Theory in Nine Chapters (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85014-8.

External links

- The Prime Glossary: Abundant number

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Abundant Number". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/AbundantNumber.html.

- Abundant number at PlanetMath.org.

|