Quantum group

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

In mathematics and theoretical physics, the term quantum group denotes one of a few different kinds of noncommutative algebras with additional structure. These include Drinfeld–Jimbo type quantum groups (which are quasitriangular Hopf algebras), compact matrix quantum groups (which are structures on unital separable C*-algebras), and bicrossproduct quantum groups. Despite their name, they do not themselves have a natural group structure, though they are in some sense 'close' to a group.

The term "quantum group" first appeared in the theory of quantum integrable systems, which was then formalized by Vladimir Drinfeld and Michio Jimbo as a particular class of Hopf algebra. The same term is also used for other Hopf algebras that deform or are close to classical Lie groups or Lie algebras, such as a "bicrossproduct" class of quantum groups introduced by Shahn Majid a little after the work of Drinfeld and Jimbo.

In Drinfeld's approach, quantum groups arise as Hopf algebras depending on an auxiliary parameter q or h, which become universal enveloping algebras of a certain Lie algebra, frequently semisimple or affine, when q = 1 or h = 0. Closely related are certain dual objects, also Hopf algebras and also called quantum groups, deforming the algebra of functions on the corresponding semisimple algebraic group or a compact Lie group.

Intuitive meaning

The discovery of quantum groups was quite unexpected since it was known for a long time that compact groups and semisimple Lie algebras are "rigid" objects, in other words, they cannot be "deformed". One of the ideas behind quantum groups is that if we consider a structure that is in a sense equivalent but larger, namely a group algebra or a universal enveloping algebra, then a group algebra or enveloping algebra can be "deformed", although the deformation will no longer remain a group algebra or enveloping algebra. More precisely, deformation can be accomplished within the category of Hopf algebras that are not required to be either commutative or cocommutative. One can think of the deformed object as an algebra of functions on a "noncommutative space", in the spirit of the noncommutative geometry of Alain Connes. This intuition, however, came after particular classes of quantum groups had already proved their usefulness in the study of the quantum Yang–Baxter equation and quantum inverse scattering method developed by the Leningrad School (Ludwig Faddeev, Leon Takhtajan, Evgeny Sklyanin, Nicolai Reshetikhin and Vladimir Korepin) and related work by the Japanese School.[1] The intuition behind the second, bicrossproduct, class of quantum groups was different and came from the search for self-dual objects as an approach to quantum gravity.[2]

Drinfeld–Jimbo type quantum groups

One type of objects commonly called a "quantum group" appeared in the work of Vladimir Drinfeld and Michio Jimbo as a deformation of the universal enveloping algebra of a semisimple Lie algebra or, more generally, a Kac–Moody algebra, in the category of Hopf algebras. The resulting algebra has additional structure, making it into a quasitriangular Hopf algebra.

Let A = (aij) be the Cartan matrix of the Kac–Moody algebra, and let q ≠ 0, 1 be a complex number, then the quantum group, Uq(G), where G is the Lie algebra whose Cartan matrix is A, is defined as the unital associative algebra with generators kλ (where λ is an element of the weight lattice, i.e. 2(λ, αi)/(αi, αi) is an integer for all i), and ei and fi (for simple roots, αi), subject to the following relations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} k_0 &= 1 \\ k_\lambda k_\mu &= k_{\lambda+\mu} \\ k_\lambda e_i k_\lambda^{-1} &= q^{(\lambda,\alpha_i)} e_i \\ k_\lambda f_i k_\lambda^{-1} &= q^{- (\lambda,\alpha_i)} f_i \\ \left [e_i, f_j \right ] &= \delta_{ij} \frac{k_i - k_i^{-1}}{q_i - q_i^{-1}} && k_i = k_{\alpha_i}, q_i = q^{\frac{1}{2}(\alpha_i,\alpha_i)} \\ \end{align} }[/math]

And for i ≠ j we have the q-Serre relations, which are deformations of the Serre relations:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \sum_{n=0}^{1 - a_{ij}} (-1)^n \frac{[1 - a_{ij}]_{q_i}!}{[1 - a_{ij} - n]_{q_i}! [n]_{q_i}!} e_i^n e_j e_i^{1 - a_{ij} - n} &= 0 \\[6pt] \sum_{n=0}^{1 - a_{ij}} (-1)^n \frac{[1 - a_{ij}]_{q_i}!}{[1 - a_{ij} - n]_{q_i}! [n]_{q_i}!} f_i^n f_j f_i^{1 - a_{ij} - n} &= 0 \end{align} }[/math]

where the q-factorial, the q-analog of the ordinary factorial, is defined recursively using q-number:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} {[0]}_{q_i}! &= 1 \\ {[n]}_{q_i}! &= \prod_{m=1}^n [m]_{q_i}, && [m]_{q_i} = \frac{q_i^m - q_i^{-m}}{q_i - q_i^{-1}} \end{align} }[/math]

In the limit as q → 1, these relations approach the relations for the universal enveloping algebra U(G), where

- [math]\displaystyle{ k_{\lambda} \to 1, \qquad \frac{k_\lambda - k_{-\lambda}}{q - q^{-1}} \to t_\lambda }[/math]

and tλ is the element of the Cartan subalgebra satisfying (tλ, h) = λ(h) for all h in the Cartan subalgebra.

There are various coassociative coproducts under which these algebras are Hopf algebras, for example,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{lll} \Delta_1(k_\lambda) = k_\lambda \otimes k_\lambda & \Delta_1(e_i) = 1 \otimes e_i + e_i \otimes k_i & \Delta_1(f_i) = k_i^{-1} \otimes f_i + f_i \otimes 1 \\ \Delta_2(k_\lambda) = k_\lambda \otimes k_\lambda & \Delta_2(e_i) = k_i^{-1} \otimes e_i + e_i \otimes 1 & \Delta_2(f_i) = 1 \otimes f_i + f_i \otimes k_i \\ \Delta_3(k_\lambda) = k_\lambda \otimes k_\lambda & \Delta_3(e_i) = k_i^{-\frac{1}{2}} \otimes e_i + e_i \otimes k_i^{\frac{1}{2}} & \Delta_3(f_i) = k_i^{-\frac{1}{2}} \otimes f_i + f_i \otimes k_i^{\frac{1}{2}} \end{array} }[/math]

where the set of generators has been extended, if required, to include kλ for λ which is expressible as the sum of an element of the weight lattice and half an element of the root lattice.

In addition, any Hopf algebra leads to another with reversed coproduct T o Δ, where T is given by T(x ⊗ y) = y ⊗ x, giving three more possible versions.

The counit on Uq(A) is the same for all these coproducts: ε(kλ) = 1, ε(ei) = ε(fi) = 0, and the respective antipodes for the above coproducts are given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{lll} S_1(k_\lambda) = k_{-\lambda} & S_1(e_i) = - e_i k_i^{-1} & S_1(f_i) = - k_i f_i \\ S_2(k_\lambda) = k_{-\lambda} & S_2(e_i) = - k_i e_i & S_2(f_i) = - f_i k_i^{-1} \\ S_3(k_\lambda) = k_{-\lambda} & S_3(e_i) = - q_i e_i & S_3(f_i) = - q_i^{-1} f_i \end{array} }[/math]

Alternatively, the quantum group Uq(G) can be regarded as an algebra over the field C(q), the field of all rational functions of an indeterminate q over C.

Similarly, the quantum group Uq(G) can be regarded as an algebra over the field Q(q), the field of all rational functions of an indeterminate q over Q (see below in the section on quantum groups at q = 0). The center of quantum group can be described by quantum determinant.

Representation theory

Just as there are many different types of representations for Kac–Moody algebras and their universal enveloping algebras, so there are many different types of representation for quantum groups.

As is the case for all Hopf algebras, Uq(G) has an adjoint representation on itself as a module, with the action being given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{Ad}_x \cdot y = \sum_{(x)} x_{(1)} y S(x_{(2)}), }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta(x) = \sum_{(x)} x_{(1)} \otimes x_{(2)}. }[/math]

Case 1: q is not a root of unity

One important type of representation is a weight representation, and the corresponding module is called a weight module. A weight module is a module with a basis of weight vectors. A weight vector is a nonzero vector v such that kλ · v = dλv for all λ, where dλ are complex numbers for all weights λ such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ d_0 = 1, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ d_\lambda d_\mu = d_{\lambda + \mu}, }[/math] for all weights λ and μ.

A weight module is called integrable if the actions of ei and fi are locally nilpotent (i.e. for any vector v in the module, there exists a positive integer k, possibly dependent on v, such that [math]\displaystyle{ e_i^k.v = f_i^k.v = 0 }[/math] for all i). In the case of integrable modules, the complex numbers dλ associated with a weight vector satisfy [math]\displaystyle{ d_\lambda = c_\lambda q^{(\lambda,\nu)} }[/math],[citation needed] where ν is an element of the weight lattice, and cλ are complex numbers such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_0 = 1, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_\lambda c_\mu = c_{\lambda + \mu}, }[/math] for all weights λ and μ,

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_{2\alpha_i} = 1 }[/math] for all i.

Of special interest are highest-weight representations, and the corresponding highest weight modules. A highest weight module is a module generated by a weight vector v, subject to kλ · v = dλv for all weights μ, and ei · v = 0 for all i. Similarly, a quantum group can have a lowest weight representation and lowest weight module, i.e. a module generated by a weight vector v, subject to kλ · v = dλv for all weights λ, and fi · v = 0 for all i.

Define a vector v to have weight ν if [math]\displaystyle{ k_\lambda\cdot v = q^{(\lambda,\nu)} v }[/math] for all λ in the weight lattice.

If G is a Kac–Moody algebra, then in any irreducible highest weight representation of Uq(G), with highest weight ν, the multiplicities of the weights are equal to their multiplicities in an irreducible representation of U(G) with equal highest weight. If the highest weight is dominant and integral (a weight μ is dominant and integral if μ satisfies the condition that [math]\displaystyle{ 2 (\mu,\alpha_i)/(\alpha_i,\alpha_i) }[/math] is a non-negative integer for all i), then the weight spectrum of the irreducible representation is invariant under the Weyl group for G, and the representation is integrable.

Conversely, if a highest weight module is integrable, then its highest weight vector v satisfies [math]\displaystyle{ k_\lambda\cdot v = c_\lambda q^{(\lambda,\nu)} v }[/math], where cλ · v = dλv are complex numbers such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_0 = 1, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_\lambda c_\mu = c_{\lambda + \mu}, }[/math] for all weights λ and μ,

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_{2\alpha_i} = 1 }[/math] for all i,

and ν is dominant and integral.

As is the case for all Hopf algebras, the tensor product of two modules is another module. For an element x of Uq(G), and for vectors v and w in the respective modules, x ⋅ (v ⊗ w) = Δ(x) ⋅ (v ⊗ w), so that [math]\displaystyle{ k_\lambda\cdot(v \otimes w) = k_\lambda\cdot v \otimes k_\lambda.w }[/math], and in the case of coproduct Δ1, [math]\displaystyle{ e_i\cdot(v \otimes w) = k_i\cdot v \otimes e_i\cdot w + e_i\cdot v \otimes w }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f_i\cdot(v \otimes w) = v \otimes f_i\cdot w + f_i\cdot v \otimes k_i^{-1}\cdot w. }[/math]

The integrable highest weight module described above is a tensor product of a one-dimensional module (on which kλ = cλ for all λ, and ei = fi = 0 for all i) and a highest weight module generated by a nonzero vector v0, subject to [math]\displaystyle{ k_\lambda\cdot v_0 = q^{(\lambda,\nu)} v_0 }[/math] for all weights λ, and [math]\displaystyle{ e_i\cdot v_0 = 0 }[/math] for all i.

In the specific case where G is a finite-dimensional Lie algebra (as a special case of a Kac–Moody algebra), then the irreducible representations with dominant integral highest weights are also finite-dimensional.

In the case of a tensor product of highest weight modules, its decomposition into submodules is the same as for the tensor product of the corresponding modules of the Kac–Moody algebra (the highest weights are the same, as are their multiplicities).

Case 2: q is a root of unity

Quasitriangularity

Case 1: q is not a root of unity

Strictly, the quantum group Uq(G) is not quasitriangular, but it can be thought of as being "nearly quasitriangular" in that there exists an infinite formal sum which plays the role of an R-matrix. This infinite formal sum is expressible in terms of generators ei and fi, and Cartan generators tλ, where kλ is formally identified with qtλ. The infinite formal sum is the product of two factors,[citation needed]

- [math]\displaystyle{ q^{\eta \sum_j t_{\lambda_j} \otimes t_{\mu_j}} }[/math]

and an infinite formal sum, where λj is a basis for the dual space to the Cartan subalgebra, and μj is the dual basis, and η = ±1.

The formal infinite sum which plays the part of the R-matrix has a well-defined action on the tensor product of two irreducible highest weight modules, and also on the tensor product of two lowest weight modules. Specifically, if v has weight α and w has weight β, then

- [math]\displaystyle{ q^{\eta \sum_j t_{\lambda_j} \otimes t_{\mu_j}}\cdot(v \otimes w) = q^{\eta (\alpha,\beta)} v \otimes w, }[/math]

and the fact that the modules are both highest weight modules or both lowest weight modules reduces the action of the other factor on v ⊗ W to a finite sum.

Specifically, if V is a highest weight module, then the formal infinite sum, R, has a well-defined, and invertible, action on V ⊗ V, and this value of R (as an element of End(V ⊗ V)) satisfies the Yang–Baxter equation, and therefore allows us to determine a representation of the braid group, and to define quasi-invariants for knots, links and braids.

Case 2: q is a root of unity

Quantum groups at q = 0

Masaki Kashiwara has researched the limiting behaviour of quantum groups as q → 0, and found a particularly well behaved base called a crystal base.

Description and classification by root-systems and Dynkin diagrams

There has been considerable progress in describing finite quotients of quantum groups such as the above Uq(g) for qn = 1; one usually considers the class of pointed Hopf algebras, meaning that all simple left or right comodules are 1-dimensional and thus the sum of all its simple subcoalgebras forms a group algebra called the coradical:

- In 2002 H.-J. Schneider and N. Andruskiewitsch [3] finished their classification of pointed Hopf algebras with an abelian co-radical group (excluding primes 2, 3, 5, 7), especially as the above finite quotients of Uq(g) decompose into E′s (Borel part), dual F′s and K′s (Cartan algebra) just like ordinary Semisimple Lie algebras:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\mathfrak{B}(V)\otimes k[\mathbf{Z}^n]\otimes\mathfrak{B}(V^*)\right)^\sigma }[/math]

- Here, as in the classical theory V is a braided vector space of dimension n spanned by the E′s, and σ (a so-called cocylce twist) creates the nontrivial linking between E′s and F′s. Note that in contrast to classical theory, more than two linked components may appear. The role of the quantum Borel algebra is taken by a Nichols algebra [math]\displaystyle{ \mathfrak{B}(V) }[/math] of the braided vectorspace.

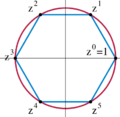

- A crucial ingredient was I. Heckenberger's classification of finite Nichols algebras for abelian groups in terms of generalized Dynkin diagrams.[4] When small primes are present, some exotic examples, such as a triangle, occur (see also the Figure of a rank 3 Dankin diagram).

- Meanwhile, Schneider and Heckenberger[5] have generally proven the existence of an arithmetic root system also in the nonabelian case, generating a PBW basis as proven by Kharcheko in the abelian case (without the assumption on finite dimension). This can be used[6] on specific cases Uq(g) and explains e.g. the numerical coincidence between certain coideal subalgebras of these quantum groups and the order of the Weyl group of the Lie algebra g.

Compact matrix quantum groups

S. L. Woronowicz introduced compact matrix quantum groups. Compact matrix quantum groups are abstract structures on which the "continuous functions" on the structure are given by elements of a C*-algebra. The geometry of a compact matrix quantum group is a special case of a noncommutative geometry.

The continuous complex-valued functions on a compact Hausdorff topological space form a commutative C*-algebra. By the Gelfand theorem, a commutative C*-algebra is isomorphic to the C*-algebra of continuous complex-valued functions on a compact Hausdorff topological space, and the topological space is uniquely determined by the C*-algebra up to homeomorphism.

For a compact topological group, G, there exists a C*-algebra homomorphism Δ: C(G) → C(G) ⊗ C(G) (where C(G) ⊗ C(G) is the C*-algebra tensor product - the completion of the algebraic tensor product of C(G) and C(G)), such that Δ(f)(x, y) = f(xy) for all f ∈ C(G), and for all x, y ∈ G (where (f ⊗ g)(x, y) = f(x)g(y) for all f, g ∈ C(G) and all x, y ∈ G). There also exists a linear multiplicative mapping κ: C(G) → C(G), such that κ(f)(x) = f(x−1) for all f ∈ C(G) and all x ∈ G. Strictly, this does not make C(G) a Hopf algebra, unless G is finite. On the other hand, a finite-dimensional representation of G can be used to generate a *-subalgebra of C(G) which is also a Hopf *-algebra. Specifically, if [math]\displaystyle{ g \mapsto (u_{ij}(g))_{i,j} }[/math] is an n-dimensional representation of G, then for all i, j uij ∈ C(G) and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta(u_{ij}) = \sum_k u_{ik} \otimes u_{kj}. }[/math]

It follows that the *-algebra generated by uij for all i, j and κ(uij) for all i, j is a Hopf *-algebra: the counit is determined by ε(uij) = δij for all i, j (where δij is the Kronecker delta), the antipode is κ, and the unit is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ 1 = \sum_k u_{1k} \kappa(u_{k1}) = \sum_k \kappa(u_{1k}) u_{k1}. }[/math]

General definition

As a generalization, a compact matrix quantum group is defined as a pair (C, u), where C is a C*-algebra and [math]\displaystyle{ u = (u_{ij})_{i,j = 1,\dots,n} }[/math] is a matrix with entries in C such that

- The *-subalgebra, C0, of C, which is generated by the matrix elements of u, is dense in C;

- There exists a C*-algebra homomorphism called the comultiplication Δ: C → C ⊗ C (where C ⊗ C is the C*-algebra tensor product - the completion of the algebraic tensor product of C and C) such that for all i, j we have:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta(u_{ij}) = \sum_k u_{ik} \otimes u_{kj} }[/math]

- There exists a linear antimultiplicative map κ: C0 → C0 (the coinverse) such that κ(κ(v*)*) = v for all v ∈ C0 and

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_k \kappa(u_{ik}) u_{kj} = \sum_k u_{ik} \kappa(u_{kj}) = \delta_{ij} I, }[/math]

where I is the identity element of C. Since κ is antimultiplicative, then κ(vw) = κ(w) κ(v) for all v, w in C0.

As a consequence of continuity, the comultiplication on C is coassociative.

In general, C is not a bialgebra, and C0 is a Hopf *-algebra.

Informally, C can be regarded as the *-algebra of continuous complex-valued functions over the compact matrix quantum group, and u can be regarded as a finite-dimensional representation of the compact matrix quantum group.

Representations

A representation of the compact matrix quantum group is given by a corepresentation of the Hopf *-algebra (a corepresentation of a counital coassociative coalgebra A is a square matrix [math]\displaystyle{ v = (v_{ij})_{i,j = 1,\dots,n} }[/math] with entries in A (so v belongs to M(n, A)) such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta(v_{ij}) = \sum_{k=1}^n v_{ik} \otimes v_{kj} }[/math]

for all i, j and ε(vij) = δij for all i, j). Furthermore, a representation v, is called unitary if the matrix for v is unitary (or equivalently, if κ(vij) = v*ij for all i, j).

Example

An example of a compact matrix quantum group is SUμ(2), where the parameter μ is a positive real number. So SUμ(2) = (C(SUμ(2)), u), where C(SUμ(2)) is the C*-algebra generated by α and γ, subject to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma \gamma^* = \gamma^* \gamma, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \gamma = \mu \gamma \alpha, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \gamma^* = \mu \gamma^* \alpha, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \alpha^* + \mu \gamma^* \gamma = \alpha^* \alpha + \mu^{-1} \gamma^* \gamma = I, }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ u = \left( \begin{matrix} \alpha & \gamma \\ - \gamma^* & \alpha^* \end{matrix} \right), }[/math]

so that the comultiplication is determined by ∆(α) = α ⊗ α − γ ⊗ γ*, ∆(γ) = α ⊗ γ + γ ⊗ α*, and the coinverse is determined by κ(α) = α*, κ(γ) = −μ−1γ, κ(γ*) = −μγ*, κ(α*) = α. Note that u is a representation, but not a unitary representation. u is equivalent to the unitary representation

- [math]\displaystyle{ v = \left( \begin{matrix} \alpha & \sqrt{\mu} \gamma \\ - \frac{1}{\sqrt{\mu}} \gamma^* & \alpha^* \end{matrix} \right). }[/math]

Equivalently, SUμ(2) = (C(SUμ(2)), w), where C(SUμ(2)) is the C*-algebra generated by α and β, subject to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \beta^* = \beta^* \beta, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \beta = \mu \beta \alpha, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \beta^* = \mu \beta^* \alpha, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \alpha^* + \mu^2 \beta^* \beta = \alpha^* \alpha + \beta^* \beta = I, }[/math]

and

- [math]\displaystyle{ w = \left( \begin{matrix} \alpha & \mu \beta \\ - \beta^* & \alpha^* \end{matrix} \right), }[/math]

so that the comultiplication is determined by ∆(α) = α ⊗ α − μβ ⊗ β*, Δ(β) = α ⊗ β + β ⊗ α*, and the coinverse is determined by κ(α) = α*, κ(β) = −μ−1β, κ(β*) = −μβ*, κ(α*) = α. Note that w is a unitary representation. The realizations can be identified by equating [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma = \sqrt{\mu} \beta }[/math].

When μ = 1, then SUμ(2) is equal to the algebra C(SU(2)) of functions on the concrete compact group SU(2).

Bicrossproduct quantum groups

Whereas compact matrix pseudogroups are typically versions of Drinfeld-Jimbo quantum groups in a dual function algebra formulation, with additional structure, the bicrossproduct ones are a distinct second family of quantum groups of increasing importance as deformations of solvable rather than semisimple Lie groups. They are associated to Lie splittings of Lie algebras or local factorisations of Lie groups and can be viewed as the cross product or Mackey quantisation of one of the factors acting on the other for the algebra and a similar story for the coproduct Δ with the second factor acting back on the first.

The very simplest nontrivial example corresponds to two copies of R locally acting on each other and results in a quantum group (given here in an algebraic form) with generators p, K, K−1, say, and coproduct

- [math]\displaystyle{ [p, K]=h K(K-1) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta p=p\otimes K+1\otimes p }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta K=K\otimes K }[/math]

where h is the deformation parameter.

This quantum group was linked to a toy model of Planck scale physics implementing Born reciprocity when viewed as a deformation of the Heisenberg algebra of quantum mechanics. Also, starting with any compact real form of a semisimple Lie algebra g its complexification as a real Lie algebra of twice the dimension splits into g and a certain solvable Lie algebra (the Iwasawa decomposition), and this provides a canonical bicrossproduct quantum group associated to g. For su(2) one obtains a quantum group deformation of the Euclidean group E(3) of motions in 3 dimensions.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Schwiebert, Christian (1994), Generalized quantum inverse scattering, pp. 12237, Bibcode: 1994hep.th...12237S

- ↑ Majid, Shahn (1988), "Hopf algebras for physics at the Planck scale", Classical and Quantum Gravity 5 (12): 1587–1607, doi:10.1088/0264-9381/5/12/010, Bibcode: 1988CQGra...5.1587M

- ↑ Andruskiewitsch, Schneider: Pointed Hopf algebras, New directions in Hopf algebras, 1–68, Math. Sci. Res. Inst. Publ., 43, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2002.

- ↑ Heckenberger: Nichols algebras of diagonal type and arithmetic root systems, Habilitation thesis 2005.

- ↑ Heckenberger, Schneider: Root system and Weyl gruppoid for Nichols algebras, 2008.

- ↑ Heckenberger, Schneider: Right coideal subalgebras of Nichols algebras and the Duflo order of the Weyl grupoid, 2009.

References

- Grensing, Gerhard (2013). Structural Aspects of Quantum Field Theory and Noncommutative Geometry. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/8771. ISBN 978-981-4472-69-2.

- Jagannathan, R. (2001). "Some introductory notes on quantum groups, quantum algebras, and their applications". arXiv:math-ph/0105002.

- Kassel, Christian (1995), Quantum groups, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 155, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0783-2, ISBN 978-0-387-94370-1, https://archive.org/details/quantumgroups0000kass

- Lusztig, George (2010). Introduction to Quantum Groups. Cambridge, MA: Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-817-64716-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=HKPjCUiOUQ0C.

- Majid, Shahn (2002), A quantum groups primer, London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series, 292, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511549892, ISBN 978-0-521-01041-2

- Majid, Shahn (January 2006), "What Is...a Quantum Group?", Notices of the American Mathematical Society 53 (1): 30–31, https://www.ams.org/notices/200601/what-is.pdf, retrieved 2008-01-16

- Podles, P.; Muller, E. (1998), "Introduction to quantum groups", Reviews in Mathematical Physics 10 (4): 511–551, doi:10.1142/S0129055X98000173, Bibcode: 1997q.alg.....4002P

- Shnider, Steven; Sternberg, Shlomo (1993). Quantum groups: From coalgebras to Drinfeld algebras. Graduate Texts in Mathematical Physics. 2. Cambridge, MA: International Press.

- Street, Ross (2007), Quantum groups, Australian Mathematical Society Lecture Series, 19, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511618505, ISBN 978-0-521-69524-4

|