Chemistry:Aminopterin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

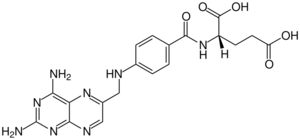

N-(4-{[(2,4-Diaminopteridin-6-yl)methyl]amino}benzoyl)-L-glutamic acid

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2S)-2-(4-{[(2,4-Diaminopteridin-6-yl)methyl]amino}benzamido)pentanedioic acid | |

| Other names

4-Aminofolic acid

4-Aminopteroylglutamic acid Aminopterin sodium Aminopteroylglutamic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

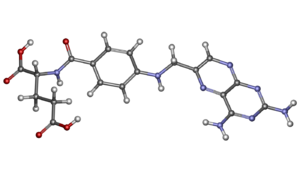

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C19H20N8O5 | |

| Molar mass | 440.41 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Aminopterin (or 4-aminopteroic acid), the 4–amino derivative of folic acid, is an antineoplastic drug with immunosuppressive properties often used in chemotherapy. Aminopterin is a synthetic derivative of pterin. Aminopterin works as an enzyme inhibitor by competing for the folate binding site of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase. Its binding affinity for dihydrofolate reductase effectively blocks tetrahydrofolate synthesis. This results in the depletion of nucleotide precursors and inhibition of DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[1]

Uses

Discovered by Yellapragada Subbarow, the drug was first used by Sidney Farber in 1947 to induce remissions among children with leukemia.[2][3] Aminopterin was later marketed by Lederle Laboratories (Pearl River, New York) in the United States from 1953 to 1964 for the indication of pediatric leukemia. The closely related antifolate methotrexate was simultaneously marketed by the company during the same period. Aminopterin was discontinued by Lederle Laboratories in favor of methotrexate due to manufacturing difficulties of the former.

During the period Aminopterin was marketed, the agent was used off-label to safely treat over 4,000 patients with psoriasis in the United States, producing dramatic clearing of lesions.[4]

The use of aminopterin in cancer treatment was supplanted in the 1950s by methotrexate due to the latter's better therapeutic index in a rodent tumor model.[5] Now in a more pure preparation and supported by laboratory evidence of superior tumor cell uptake in vitro, aminopterin is being investigated in clinical trials in leukemia as a potentially superior antifolate to methotrexate.[6]

The compound was explored as an abortifacient in the 1960s and earlier, but was associated with congenital malformations.[7] Similar congenital abnormalities have been documented with methotrexate, and collectively their teratogenic effects have become known as the fetal aminopterin syndrome. When a similar cluster of anomalies appears in the absence of exposure to antifolates it is referred to as aminopterin-like syndrome without aminopterin.[8]

The reference to the use of Aminopterin as a rodenticide (i.e. rat poison) dates back to a 1951 patent issued to the American Cyanamid Company that is commonly cited by a variety of reference textbooks including the Merck Manual, although the use of aminopterin as a rodenticide was later disputed.[9] The preparation of the molecule is complex and expensive. It is also unstable in the environment due to degradation by light and heat. The apparently mistaken association of aminopterin with its use as a rodenticide likely dates back to a 1951 patent issued to the American Cyanamid Company (then the holding company of Lederle Laboratories) that is commonly cited by a variety of reference textbooks.[10] Aminopterin has a single-dose LDLo of 2.5 mg/kg when orally administered to rats.[11]

Aminopterin is widely used in selection media (such as HAT medium) for cell culture, particularly in the development of hybridomas, which secrete monoclonal antibodies.

Implication in 2007 Menu Foods recall

On March 23, 2007, ABC News reported[12] that aminopterin was the chemical linked to the 2007 Menu Foods pet food contamination incident. The incident resulted in a massive recall of the affected foods.[13] The link to aminopterin was confirmed by New York State Agriculture Commissioner Patrick Hooker and Dr. Donald Smith, Dean of Cornell University's College of Veterinary Medicine, in a statement released on the same day.[14][15]

On March 27, the ASPCA Animal Poison Control Center expressed concern that the problem may not yet be fully understood and that other contaminants may be involved, noting that "clinical signs reported in cats affected by the contaminated foods are not fully consistent with the ingestion of rat poison containing aminopterin".[16] On March 30 it was widely reported that the United States Food and Drug Administration had found melamine in wheat gluten that was used in the pet foods in question. These same reports stated that the FDA had failed to find evidence of aminopterin in the wheat gluten. Tests at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada detected aminopterin in some pet food samples, but only in concentrations of parts per billion or parts per trillion, amounts too low to cause the symptoms seen.[17]

Exposure and treatment

Symptoms of exposure in humans include:[18] [19]

- nausea

- vomiting

- anorexia

- weight loss

- chills

- fever

- stomatitis – inflammation of the oral mucosa

- pharyngitis – inflammation of the pharynx

- erythematous rashes – red rashes on the skin

- hyperpigmentation – increased pigmentation associated with cleared psoriatic lesions

- gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- renal failure – in high doses necessarily involving concomitant leucovorin rescue

- abortions in pregnant women

Supralethal doses of aminopterin may be rescued with the antidote Leucovorin (also known as folinic acid), a reduced form of folic acid which bypasses dihydrofolate reductase, the enzyme inhibited by aminopterin. Leucovorin has been used in rats, dogs and humans to rescue aminopterin toxicity.[20][21][22][23] Leucovorin rescue is a therapeutic maneuver intentionally employed with antifolates to achieve tumoricidal drug concentrations that would otherwise be lethal to the patient.[6]

In humans, leucovorin rescue at overdosages lower than 10 mg aminopterin in an average 70 kg adult should comprise an initial leucovorin dose of at least 20 mg (10.0 mg/m2), given intravenously (preferably), or orally.[23] Subsequent doses of 20 mg (which may be taken orally) should be given at 6 hour intervals until hematological abnormalities are improved.

Massive aminopterin overdosage in humans (i.e. > 40 mg AMT in an average 70 kg adult), should be approached with an initial leucovorin dose of 100 mg (50 mg/m2), given intravenously and continued at 6 hour intervals until the hematological abnormalities are improved (likely 8–12 courses or more).[22] Additionally, to prevent reversible aminopterin-mediated nephrotoxicity manifesting as increases in serum creatinine and which further delays drug elimination, urinary alkalinization with NaHCO3 and volume expansion should be considered in cases of massive aminopterin overdosage, particularly those involving greater than 100 mg AMT in an average 70 kg adult human.

Consistent with the known enterohepatic cycling of the related antifolate methotrexate, oral activated charcoal, and saline cathartic or sorbitol may promote excretion if an overdose of aminopterin is suspected. However, rescue with leucovorin should form the backbone of treatment.

The vitamin folic acid is an oxidized precursor to reduced folates that is upstream of the blockade at dihydrofolate reductase, and compared to leucovorin is recognized as a very weak antidote to the toxic effects of antifolates that is inappropriate for use in cases of acute intoxication. Minnich et al. dosed mongrel dogs subcutaneously with aminopterin and folic acid simultaneously to test whether folic acid can rescue animals from the lethality and toxicity of aminopterin[24] Dogs were given 0.020, 0.046, 0.044 escalated to 0.088, and 0.097 mg/kg aminopterin each day for 7 to 12 days. Folic acid was given in a weight ratio to aminopterin of 200:1 to 800:1. All animals survived. In contrast, animals given aminopterin in an amount of 0.041 mg/kg/day x 6 days without folic acid died. Thus, when the ratio of folic acid to aminopterin was 200:1 and greater, all of the subjects survived on regimens that would have otherwise been uniformly fatal to all subjects.

Similar effects have been noted in rodent species as well, where the range for rescue by folic acid was fairly narrow and highly dependent on the timing (optimal of 1 hour prior to aminopterin) of administration in relation to aminopterin.[25][26] The temporal relationship between folic acid administration and rescue has been interpreted as the necessary period of time required for the vitamin to be converted in vivo to reduced forms.

References

- ↑ 40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. http://edocket.access.gpo.gov/cfr_2008/julqtr/pdf/40cfr355AppA.pdf. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Who was Sidney Farber, MD?". Dana–Farber Cancer Institute. http://www.dana-farber.org/About-Us/History-and-Milestones.aspx.

- ↑ "Temporary remissions in acute leukemia in children produced by folic acid antagonist, 4-Aminopteroyl-glutamic acid (Aminopterin)". N Engl J Med 238 (787): 787–93. 1948. doi:10.1056/NEJM194806032382301. PMID 18860765.

- ↑ "Aminopterin for Psoriasis. A decade's observation". Arch Dermatol 90 (6): 544–52. December 1964. doi:10.1001/archderm.1964.01600060010002. PMID 14206858. http://archderm.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14206858.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "A quantitative comparison of the antileukemic effectiveness of two folic acid antagonists in mice". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 15 (6): 1657–64. June 1955. doi:10.1093/jnci/15.6.1657. PMID 14381889.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cole, PD; Drachtman, RA; Smith, AK; Cate, S; Larson, RA; Hawkins, DS; Holcenberg, J; Kelly, K et al. (15 November 2005). "Phase II trial of oral aminopterin for adults and children with refractory acute leukemia.". Clinical Cancer Research 11 (22): 8089–96. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0355. PMID 16299240.

- ↑ Emerson D (August 1962). "Congenital malformation due to attempted abortion with aminopterin". Am J Obstet Gynecol 84 (3): 356–7. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(62)90132-1. PMID 13890101.

- ↑ "Multiple Congenital Anomaly/Mental Retardation (MCA/MR) Syndromes: Fetal aminopterin syndrome". United States National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/jablonski/syndromes/syndrome289.html.

- ↑ "No Aminopterin in Tissues of Animals Killed by Recalled Pet Food". PRNewsWire. March 30, 2007. http://www.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=109&STORY=/www/story/03-30-2007/0004557052&EDATE=.

- ↑ Franklin, Alfred L., "Rodenticide comprising 4-amino-pteroylglutamic acid", US patent 2575168, published November 13, 1951, assigned to American Cyanamid Company

- ↑ "EPA Chemical Profile: Aminopterin". United States Environmental Protection Agency. October 31, 1985. http://yosemite.epa.gov/oswer/ceppoehs.nsf/Profiles/54-62-6!OpenDocument.

- ↑ Kerley, David (March 23, 2007). "Rat Poison to Blame for Pet Food Contamination". ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/story?id=2975912&page=1&US=true.

- ↑ "Menu Foods Issues Recall Of Specific Can And Small Foil Pouch Wet Pet Foods". New York Department of Agriculture. March 16, 2007. http://www.agriculture.ny.gov/AD/alert.asp?ReleaseID=685.

- ↑ Johnson, Mark (March 23, 2007). "Rat poison found in tainted pet food". BusinessWeek. http://www.businessweek.com/ap/financialnews/D8O20JHO0.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ↑ "New York Laboratories Identify Toxin In Recalled Pet Food". New York Department of Agriculture. March 23, 2007. http://www.agriculture.ny.gov/AD/release.asp?ReleaseID=1598.

- ↑ "ASPCA Advises Caution As Pet Food Recall Crisis Grows; Other Contaminants May Be Involved in the Menu Foods Recall". March 27, 2007. http://www.aspca.org/site/PageServer?pagename=press_032707_2.

- ↑ "FDA finds new chemical in recalled pet food, sick animals". CNN. March 30, 2007. http://www.cnn.com/2007/US/03/30/pet.food.recall.ap/index.html.

- ↑ "Chemical data sheet for Aminopterin". CAMEO Chemicals. U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://cameochemicals.noaa.gov/chemical/4857.

- ↑ Berenbaum, M.C.; Brown, I.N. (March 1, 1965). "The effect of delayed administration of folinic acid on immunological inhibition by methotrexate". Immunology 8 (3): 251–9. PMID 14315108.

- ↑ "On the mechanism of action of aminopterin". Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 74 (2): 403–11. June 1950. doi:10.3181/00379727-74-17922. PMID 15440837.

- ↑ "Intrathecal aminopterin therapy of meningeal leukemia". Arch. Intern. Med. 111 (5): 620–30. May 1963. doi:10.1001/archinte.1963.03620290086011. PMID 13973810. http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=13973810.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "A Phase 1 study of high doses of aminopterin with leucovorin rescue in patients with advanced metastatic tumors". Cancer Res. 39 (9): 3707–14. September 1979. PMID 383286. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=383286.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Phase I and pharmacokinetic trial of aminopterin in patients with refractory malignancies". J. Clin. Oncol. 16 (4): 1458–64. April 1998. doi:10.1200/JCO.1998.16.4.1458. PMID 9552052. http://www.jco.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9552052.

- ↑ "Studies on the acute toxic effects of 4-amino-pteroylglutamic acid in dogs, guinea pigs and rabbits. Difference in species susceptibility and protective action of folic acid". AMA Arch Pathol 50 (6): 787–99. December 1950. PMID 14789323.

- ↑ "Observations on the effect of 4-amino-pteroylglutamic acid in mice". Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 67 (3): 398–400. 1948. doi:10.3181/00379727-67-16320.

- ↑ "Studies on the mechanism of action of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. II. Requirements for the prevention of aminopterin toxicity by folic acid in mice". Cancer 3 (5): 856–63. September 1950. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:5<856::AID-CNCR2820030512>3.0.CO;2-A. PMID 14772718.

|