Chemistry:Aminolevulinic acid

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Levulan, NatuALA, Ameluz, others |

| Other names | 5-aminolevulinic acid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607062 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Topical, By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

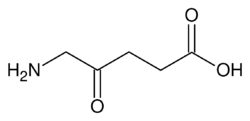

| Formula | C5H9NO3 |

| Molar mass | 131.131 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 118 °C (244 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

δ-Aminolevulinic acid (also dALA, δ-ALA, 5ALA or 5-aminolevulinic acid), an endogenous non-proteinogenic amino acid, is the first compound in the porphyrin synthesis pathway, the pathway that leads to heme[3] in mammals, as well as chlorophyll[4] in plants.

5ALA is used in photodynamic detection and surgery of cancer.[5][6][7][8]

Medical uses

As a precursor of a photosensitizer, 5ALA is also used as an add-on agent for photodynamic therapy.[9] In contrast to larger photosensitizer molecules, it is predicted by computer simulations to be able to penetrate tumor cell membranes.[10]

Cancer diagnosis

Photodynamic detection is the use of photosensitive drugs with a light source of the right wavelength for the detection of cancer, using fluorescence of the drug.[5] 5ALA, or derivatives thereof, can be used to visualize bladder cancer by fluorescence imaging.[5]

Cancer treatment

Aminolevulinic acid is being studied for photodynamic therapy (PDT) in a number of types of cancer.[11] It is not currently a first line treatment for Barrett's esophagus.[12] Its use in brain cancer is currently experimental.[13] It has been studied in a number of gynecological cancers.[14]

Aminolevulinic acid is indicated in adults for visualization of malignant tissue during surgery for malignant glioma (World Health Organization grade III and IV).[15] It is used to visualise tumorous tissue in neurosurgical procedures.[6] Studies since 2006 have shown that the intraoperative use of this guiding method may reduce the tumour residual volume and prolong progression-free survival in people with malignant gliomas.[7][8] The US FDA approved aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (ALA HCL) for this use in 2017.[16]

Intra-operative Cancer Delineation

Aminolevulinic acid utilization is promising in the field of cancer delineation, particularly in the context of fluorescence-guided surgery. This compound is utilized to enhance the visualization of malignant tissues during surgical procedures. When administered to patients, 5-ALA is metabolized to protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) preferentially in cancer cells, leading to their fluorescence under specific light wavelengths.[17] This fluorescence aids surgeons in real-time identification and precise removal of cancerous tissue, reducing the likelihood of leaving residual tumor cells behind. This innovative approach has shown success in various cancer types, including brain and spine gliomas, bladder cancer, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.[18][19][20]

Side effects

Side effects may include liver damage and nerve problems.[12] Hyperthermia may also occur.[13] Deaths have also resulted.[12]

Biosynthesis

In non-photosynthetic eukaryotes such as animals, fungi, and protozoa, as well as the class Alphaproteobacteria of bacteria, it is produced by the enzyme ALA synthase, from glycine and succinyl-CoA. This reaction is known as the Shemin pathway, which occurs in mitochondria.[21]

In plants, algae, bacteria (except for the class Alphaproteobacteria) and archaea, it is produced from glutamic acid via glutamyl-tRNA and glutamate-1-semialdehyde. The enzymes involved in this pathway are glutamyl-tRNA synthetase, glutamyl-tRNA reductase, and glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase. This pathway is known as the C5 or Beale pathway.[22][23] In most plastid-containing species, glutamyl-tRNA is encoded by a plastid gene, and the transcription, as well as the following steps of C5 pathway, take place in plastids.[24]

Importance in humans

Activation of mitochondria

In humans, 5ALA is a precursor to heme.[3] Biosynthesized, 5ALA goes through a series of transformations in the cytosol and finally gets converted to Protoporphyrin IX inside the mitochondria.[25][26] This protoporphyrin molecule chelates with iron in presence of enzyme ferrochelatase to produce Heme.[25][26]

Heme increases the mitochondrial activity thereby helping in activation of respiratory system Krebs Cycle and Electron Transport Chain[27] leading to formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for adequate supply of energy to the body.[27]

Accumulation of Protoporphyrin IX

Cancer cells lack or have reduced ferrochelatase activity and this results in accumulation of Protoporphyrin IX, a fluorescent substance that can easily be visualized.[5]

Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1)

Excess heme is converted in macrophages to Biliverdin and ferrous ions by the enzyme HO-1. Biliverdin formed further gets converted to Bilirubin and carbon monoxide.[28] Biliverdin and Bilirubin are potent anti oxidants and regulate important biological processes like inflammation, apoptosis, cell proliferation, fibrosis and angiogenesis.[28]

Plants

In plants, production of 5-ALA is the step on which the speed of synthesis of chlorophyll is regulated.[4] Plants that are fed by external 5-ALA accumulate toxic amounts of chlorophyll precursor, protochlorophyllide, indicating that the synthesis of this intermediate is not suppressed anywhere downwards in the chain of reaction. Protochlorophyllide is a strong photosensitizer in plants.[29] Controlled spraying of 5-ALA at lower doses (up to 150 mg/L) can however help protect plants from stress and encourage growth.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ "Levulan Kerastick Product information". 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=67875.

- ↑ "Gleolan Product information". 25 April 2012. https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=99429.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Biosynthesis of heme in immature erythroid cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 263: 6676–6682. 1988. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68695-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Chlorophyll Biosynthesis". The Plant Cell 7 (7): 1039–1057. July 1995. doi:10.1105/tpc.7.7.1039. PMID 12242396.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Wagnières, G.., Jichlinski, P., Lange, N., Kucera, P., Van den Bergh, H. (2014). Detection of Bladder Cancer by Fluorescence Cystoscopy: From Bench to Bedside - the Hexvix Story. Handbook of Photomedicine, 411-426.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Surgical resection of malignant gliomas-role in optimizing patient outcome". Nature Reviews. Neurology 9 (3): 141–151. March 2013. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2012.279. PMID 23358480.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial". The Lancet. Oncology 7 (5): 392–401. May 2006. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(06)70665-9. PMID 16648043.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Improving the extent of malignant glioma resection by dual intraoperative visualization approach". PLOS ONE 7 (9): e44885. 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044885. PMID 23049761. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...744885E.

- ↑ "Photodynamic Therapy With Topical 5% 5-Aminolevulinic Acid for the Treatment of Truncal Acne in Asian Patients". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology 15 (6): 727–732. June 2016. PMID 27272080.

- ↑ "Modelling the behavior of 5-aminolevulinic acid and its alkyl esters in a lipid bilayer". Chemical Physics Letters 463 (1–3): 178. 2008. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2008.08.021. Bibcode: 2008CPL...463..178E.

- ↑ "5-Aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy for bladder cancer". International Journal of Urology 24 (2): 97–101. February 2017. doi:10.1111/iju.13291. PMID 28191719.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Photodynamic Therapy for Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Carcinoma". Clinical Endoscopy 46 (1): 30–37. January 2013. doi:10.5946/ce.2013.46.1.30. PMID 23423151.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Experimental use of photodynamic therapy in high grade gliomas: a review focused on 5-aminolevulinic acid". Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 11 (3): 319–330. September 2014. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2014.04.004. PMID 24905843. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01181357/file/Tetard-Vermandel-Mordon-Lejeune-Reyns.pdf.

- ↑ "Photodynamic therapy for gynecological diseases and breast cancer". Cancer Biology & Medicine 9 (1): 9–17. March 2012. doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.01.002. PMID 23691448.

- ↑ "Gliolan EPAR". 17 September 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/gliolan.

- ↑ FDA Approves Fluorescing Agent for Glioma Surgery.June 2017

- ↑ Hadjipanayis, Costas G.; Widhalm, Georg; Stummer, Walter (November 2015). "What is the Surgical Benefit of Utilizing 5-ALA for Fluorescence-Guided Surgery of Malignant Gliomas?". Neurosurgery 77 (5): 663–673. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000929. ISSN 0148-396X. PMID 26308630.

- ↑ Maragkos, Georgios A.; Schüpper, Alexander J.; Lakomkin, Nikita; Sideras, Panagiotis; Price, Gabrielle; Baron, Rebecca; Hamilton, Travis; Haider, Sameah et al. (2021). "Fluorescence-Guided High-Grade Glioma Surgery More Than Four Hours After 5-Aminolevulinic Acid Administration". Frontiers in Neurology 12. doi:10.3389/fneur.2021.644804. ISSN 1664-2295. PMID 33767664.

- ↑ Albalkhi, Ibrahem; Shafqat, Areez; Bin-Alamer, Othman; Abou Al-Shaar, Abdul Rahman; Mallela, Arka N.; Fernández-de Thomas, Ricardo J.; Zinn, Pascal O.; Gerszten, Peter C. et al. (2023-12-12). "Fluorescence-guided resection of intradural spinal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (in en). Neurosurgical Review 47 (1): 10. doi:10.1007/s10143-023-02230-x. ISSN 1437-2320. PMID 38085385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02230-x.

- ↑ Filip, Peter; Lerner, David K.; Kominsky, Evan; Schupper, Alexander; Liu, Katherine; Khan, Nazir Mohemmed; Roof, Scott; Hadjipanayis, Constantinos et al. (2023-08-04). "5-Aminolevulinic Acid Fluorescence-Guided Surgery in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma" (in en). The Laryngoscope 134 (2): 741–748. doi:10.1002/lary.30910. ISSN 0023-852X. PMID 37540051. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/lary.30910.

- ↑ Ajioka, James; Soldati, Dominique, eds. (September 13, 2007). "22". Toxoplasma: Molecular and Cellular Biology (1 ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 415. ISBN:9781904933342

- ↑ "Biosynthesis of the Tetrapyrrole Pigment Precursor, delta-Aminolevulinic Acid, from Glutamate". Plant Physiology 93 (4): 1273–1279. August 1990. doi:10.1104/pp.93.4.1273. PMID 16667613.

- ↑ Willows, R.D. (2004). "Chlorophylls". In Goodman, Robert M. Encyclopaedia of Plant and Crop Science. Marcel Dekker. pp. 258–262. ISBN:0-8247-4268-0

- ↑ Biswal, Basanti; Krupinska, Karin; Biswal, Udaya, eds. (2013). Plastid Development in Leaves during Growth and Senescence (Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration). Dordrecht: Springer. p. 508. ISBN:9789400757233

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "5-Aminolevulinic acid stimulation of porphyrin and hemoglobin synthesis by uninduced Friend erythroleukemic cells". Cell Differentiation 8 (3): 223–233. June 1979. doi:10.1016/0045-6039(79)90049-6. PMID 288514.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Advances in bio-optical imaging for the diagnosis of early oral cancer". Pharmaceutics 3 (3): 354–378. July 2011. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics3030354. PMID 24310585.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "The effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid on cytochrome c oxidase activity in mouse liver". BMC Research Notes 4 (4): 66. March 2011. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-4-66. PMID 21414200.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 73 (17): 3221–3247. September 2016. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2223-0. PMID 27100828.

- ↑ "The influence of 5-aminolevulinic acid on protochlorophyllide and protochlorophyll accumulation in dark-grown Scenedesmus". Z. Naturforsch. 45 (1–2): 71–73. 1990. doi:10.1515/znc-1990-1-212.

- ↑ "Exogenously-applied 5-aminolevulinic acid modulates some key physiological characteristics and antioxidative defense system in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings under water stress". South African Journal of Botany 96: 71–77. January 2015. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2014.10.015.

External links

- "Aminolevulinic acid". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/aminolevulinic%20acid.

|