Chemistry:Desipramine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Norpramin, Pertofrane, others |

| Other names | Desmethylimipramine; Norimipramine; EX-4355; G-35020; JB-8181; NSC-114901[1][2][3] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682387 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–70%[4] |

| Protein binding | 91%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6)[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–30 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Urine (70%), feces[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22N2 |

| Molar mass | 266.388 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Desipramine, sold under the brand name Norpramin among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA) used in the treatment of depression.[6] It acts as a relatively selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, though it does also have other activities such as weak serotonin reuptake inhibitory, α1-blocking, antihistamine, and anticholinergic effects. The drug is not considered a first-line treatment for depression since the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants, which have fewer side effects and are safer in overdose.

Medical uses

Desipramine is primarily used for the treatment of depression.[6] It may also be useful to treat symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[7] Evidence of benefit is only in the short term, and with concerns of side effects its overall usefulness is not clear.[8] Desipramine at very low doses is also used to help reduce the pain associated with functional dyspepsia.[9] It has also been tried, albeit with little evidence of effectiveness, in the treatment of cocaine dependence.[10] Evidence for usefulness in neuropathic pain is also poor.[11]

Side effects

Desipramine tends to be less sedating than other TCAs and tends to produce fewer anticholinergic effects such as dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, and cognitive or memory impairments.[12]

Overdose

Desipramine is particularly toxic in cases of overdose, compared to other antidepressants.[13] Any overdose or suspected overdose of desipramine is considered to be a medical emergency and can result in death without prompt medical intervention.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET | 0.63–3.5 | Human | [14][15] |

| DAT | 3,190 | Human | [14] |

| 5-HT1A | ≥6,400 | Human | [16][17] |

| 5-HT2A | 115–350 | Human | [16][17] |

| 5-HT2C | 244–748 | Rat | [18][19] |

| 5-HT3 | ≥2,500 | Rodent | [19][20] |

| 5-HT7 | >1,000 | Rat | [21] |

| α1 | 23–130 | Human | [16][22][15] |

| α2 | ≥1,379 | Human | [16][22][15] |

| β | ≥1,700 | Rat | [23][24] |

| Cav2.2 | 410 | Human | [25] |

| D1 | 5,460 | Human | [26] |

| D2 | 3,400 | Human | [16][22] |

| H1 | 60–110 | Human | [16][22][27] |

| H2 | 1,550 | Human | [27] |

| H3 | >100,000 | Human | [27] |

| H4 | 9,550 | Human | [27] |

| mACh | 66–198 | Human | [16][22] |

| M1 | 110 | Human | [28] |

| M2 | 540 | Human | [28] |

| M3 | 210 | Human | [28] |

| M4 | 160 | Human | [28] |

| M5 | 143 | Human | [28] |

| σ1 | 1,990–4,000 | Rodent | [29][30] |

| σ2 | ≥1,611 | Rat | [31][30] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Desipramine is a very potent and relatively selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI), which is thought to enhance noradrenergic neurotransmission.[32][33] Based on one study, it has the highest affinity for the norepinephrine transporter (NET) of any other TCA,[14] and is said to be the most noradrenergic[34] and the most selective for the NET of the TCAs.[32] The observed effectiveness of desipramine in the treatment of ADHD was the basis for the development of the selective NRI atomoxetine and its use in ADHD.[32]

Desipramine has the weakest antihistamine and anticholinergic effects of the TCAs.[35][34][36] It tends to be slightly activating/stimulating rather than sedating, unlike most others TCAs.[34] Whereas other TCAs are useful for treating insomnia, desipramine can cause insomnia as a side effect due to its activating properties.[34] The drug is also not associated with weight gain, in contrast to many other TCAs.[34] Secondary amine TCAs like desipramine and nortriptyline have a lower risk of orthostatic hypotension than other TCAs,[37][38] although desipramine can still cause moderate orthostatic hypotension.[39]

Pharmacokinetics

Desipramine is the major metabolite of imipramine and lofepramine.[40]

Chemistry

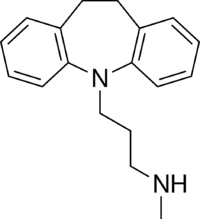

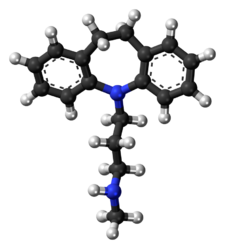

Desipramine is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzazepine, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[41] Other dibenzazepine TCAs include imipramine (N-methyldesipramine), clomipramine, trimipramine, and lofepramine (N-(4-chlorobenzoylmethyl)desipramine).[41][42] Desipramine is a secondary amine TCA, with its N-methylated parent imipramine being a tertiary amine.[43][44] Other secondary amine TCAs include nortriptyline and protriptyline.[45][46] The chemical name of desipramine is 3-(10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N-methylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C18H22N2 with a molecular weight of 266.381 g/mol.[1] The drug is used commercially mostly as the hydrochloride salt; the dibudinate salt is or has been used for intramuscular injection in Argentina (brand name Nebril) and the free base form is not used.[1][2] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 50-47-5, of the hydrochloride is 58-28-6, and of the dibudinate is 62265-06-9.[1][2][47]

History

Desipramine was developed by Geigy.[48] It first appeared in the literature in 1959 and was patented in 1962.[48] The drug was first introduced for the treatment of depression in 1963 or 1964.[48][49]

Society and culture

Generic names

Desipramine is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while desipramine hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, BAN, and JAN.[1][2][50][3] Its generic name in French and its DCF are désipramine, in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT are desipramina, in German is desipramin, and in Latin is desipraminum.[2][3]

Brand names

Desipramine is or has been marketed throughout the world under a variety of brand names, including Irene, Nebril, Norpramin, Pertofran, Pertofrane, Pertrofran, and Petylyl among others.[2][3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. 14 November 2014. pp. 363–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA363.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC&pg=PA304.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Desipramine - Drugs.com". https://www.drugs.com/international/desipramine.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 24 January 2012. pp. 588–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Sd6ot9ul-bUC&pg=PA588.

- ↑ "Clinical pharmacokinetics of imipramine and desipramine". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 18 (5): 346–364. May 1990. doi:10.2165/00003088-199018050-00002. PMID 2185906.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. 2010. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ↑ "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of desipramine for treating ADHD". Current Drug Safety 8 (3): 169–174. July 2013. doi:10.2174/15748863113089990029. PMID 23914752.

- ↑ "Tricyclic antidepressants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9 (9): CD006997. September 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006997.pub2. PMID 25238582.

- ↑ "UpToDate". http://www.uptodate.com/contents/upset-stomach-functional-dyspepsia-in-adults-beyond-the-basics.

- ↑ "Antidepressants for cocaine dependence and problematic cocaine use". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD002950. December 2011. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002950.pub3. PMID 22161371.

- ↑ "Desipramine for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 (9): CD011003. September 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011003.pub2. PMID 25246131.

- ↑ "Desipramine Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. 13 December 2013. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/current/2509-y.htm.

- ↑ "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology 4 (4): 238–250. December 2008. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9537821 - ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedpmid9400006 - ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology 114 (4): 559–565. May 1994. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology 132 (2–3): 115–121. December 1986. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ↑ "Interactions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with the serotonin 5-HT2c receptor". Psychopharmacology 126 (3): 234–240. August 1996. doi:10.1007/bf02246453. PMID 8876023.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Research Monograph 178: 440–466. March 1998. PMID 9686407.

- ↑ "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". European Journal of Pharmacology 171 (1): 141–143. November 1989. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- ↑ "Molecular cloning and expression of a 5-hydroxytryptamine7 serotonin receptor subtype". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 268 (24): 18200–18204. August 1993. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46830-X. PMID 8394362.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 230 (1): 94–102. July 1984. PMID 6086881.

- ↑ "Antidepressant biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45,030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative". Biochemical Pharmacology 35 (24): 4493–4497. December 1986. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90769-0. PMID 3790168.

- ↑ "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology 19 (4): 467–489. August 1999. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMID 10379421.

- ↑ "Pharmacological characterization of recombinant N-type calcium channel (Cav2.2) mediated calcium mobilization using FLIPR". Biochemical Pharmacology 72 (6): 770–782. September 2006. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.003. PMID 16844100.

- ↑ "Pharmacological properties of the active metabolites of the antidepressants desipramine and citalopram". European Journal of Pharmacology 576 (1–3): 55–60. December 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.08.017. PMID 17850785.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 385 (2): 145–170. February 2012. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochemical Pharmacology 45 (11): 2352–2354. June 1993. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- ↑ "1,3-Di(2-[5-3Htolyl)guanidine: a selective ligand that labels sigma-type receptors for psychotomimetic opiates and antipsychotic drugs"]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 83 (22): 8784–8788. November 1986. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.22.8784. PMID 2877462. Bibcode: 1986PNAS...83.8784W.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology 25 (3): 193–200. April 2010. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPDSP - ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Lewis's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. pp. 764–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6214-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=s9Jdn43iac8C&pg=PA764.

- ↑ "Desipramine: an overview". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 45 (10 Pt 2): 3–9. October 1984. PMID 6384207.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 Pain Management, An Issue of Hand Clinics, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 19 January 2016. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-323-41691-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=TeGZCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA55.

- ↑ Advances in Psychopharmacology. CRC Press. 2 July 1984. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-8493-5680-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=wwP1iOanWAAC&pg=PA98.

- ↑ Advanced Therapy in Gastroenterology and Liver Disease. PMPH-USA. 2005. pp. 263–. ISBN 978-1-55009-248-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=XR-Jsxz0qRwC&pg=PA263.

- ↑ Biopsychosocial Approaches in Primary Care: State of the Art and Challenges for the 21st Century. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-4615-5957-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=5kcIBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA108.

- ↑ Essentials of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Pub. 2011. pp. 468–. ISBN 978-1-58562-933-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=Hf50vMMMv_wC&pg=PA468.

- ↑ Textbook of Family Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. May 2007. pp. 313–. ISBN 978-1-4377-2190-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ntcoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA313.

- ↑ "A comparison of the pharmacological properties of the novel tricyclic antidepressant lofepramine with its major metabolite, desipramine: a review". International Clinical Psychopharmacology 2 (4): 281–297. October 1987. doi:10.1097/00004850-198710000-00001. PMID 2891742.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. 15 February 2013. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=jy-LMZU7338C&pg=PA270.

- ↑ Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. pp. 580–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=R0W1ErpsQpkC&pg=PA580.

- ↑ Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. 20 September 1994. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ncRXa8Dq88QC&pg=PA160.

- ↑ Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. 23 February 2012. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=f-XHh17NfwgC&pg=PA302.

- ↑ Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2002. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=_QQsj3PAUrEC&pg=PA39.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. 9 August 2012. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Y1DtSGq-LnoC&pg=PA532.

- ↑ "Desipramine dibudinate". ChemIDplus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://chem.nlm.nih.gov/chemidplus/rn/62265-06-9.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chemical Communications (25): 3677–3692. July 2009. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ↑ Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. pp. 836–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=BfdighlyGiwC&pg=PA836.

- ↑ Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. 6 December 2012. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=tsjrCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA94.

External links

|