Chemistry:Alcohol

In chemistry, alcohol is an organic compound that carries at least one hydroxyl functional group (−OH) bound to a saturated carbon atom.[2] The term alcohol originally referred to the primary alcohol ethanol (ethyl alcohol), which is used as a drug and is the main alcohol present in alcoholic drinks. An important class of alcohols, of which methanol and ethanol are the simplest members, includes all compounds for which the general formula is CnH2n+1OH. Simple monoalcohols that are the subject of this article include primary (RCH2OH), secondary (R2CHOH) and tertiary (R3COH) alcohols.

The suffix -ol appears in the IUPAC chemical name of all substances where the hydroxyl group is the functional group with the highest priority. When a higher priority group is present in the compound, the prefix hydroxy- is used in its IUPAC name. The suffix -ol in non-IUPAC names (such as paracetamol or cholesterol) also typically indicates that the substance is an alcohol. However, many substances that contain hydroxyl functional groups (particularly sugars, such as glucose and sucrose) have names which include neither the suffix -ol, nor the prefix hydroxy-.

History

The inflammable nature of the exhalations of wine was already known to ancient natural philosophers such as Aristotle (384–322 BCE), Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE), and Pliny the Elder (23/24–79 CE).[3] However, this did not immediately lead to the isolation of alcohol, even despite the development of more advanced distillation techniques in second- and third-century Roman Egypt.[4] An important recognition, first found in one of the writings attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (ninth century CE), was that by adding salt to boiling wine, which increases the wine's relative volatility, the flammability of the resulting vapors may be enhanced.[5] The distillation of wine is attested in Arabic works attributed to al-Kindī (c. 801–873 CE) and to al-Fārābī (c. 872–950), and in the 28th book of al-Zahrāwī's (Latin: Abulcasis, 936–1013) Kitāb al-Taṣrīf (later translated into Latin as Liber servatoris).[6] In the twelfth century, recipes for the production of aqua ardens ("burning water", i.e., alcohol) by distilling wine with salt started to appear in a number of Latin works, and by the end of the thirteenth century it had become a widely known substance among Western European chemists.[7] Its medicinal properties were studied by Arnald of Villanova (1240–1311 CE) and John of Rupescissa (c. 1310–1366), the latter of whom regarded it as a life-preserving substance able to prevent all diseases (the aqua vitae or "water of life", also called by John the quintessence of wine).[8]

Nomenclature

Etymology

The word "alcohol" is from the Arabic kohl (Arabic: الكحل), a powder used as an eyeliner.[9] Al- is the Arabic definite article, equivalent to the in English. Alcohol was originally used for the very fine powder produced by the sublimation of the natural mineral stibnite to form antimony trisulfide Sb2S3. It was considered to be the essence or "spirit" of this mineral. It was used as an antiseptic, eyeliner, and cosmetic. The meaning of alcohol was extended to distilled substances in general, and then narrowed to ethanol, when "spirits" was a synonym for hard liquor.[10]

Bartholomew Traheron, in his 1543 translation of John of Vigo, introduces the word as a term used by "barbarous" authors for "fine powder." Vigo wrote: "the barbarous auctours use alcohol, or (as I fynde it sometymes wryten) alcofoll, for moost fine poudre."[11]

The 1657 Lexicon Chymicum, by William Johnson glosses the word as "antimonium sive stibium."[12] By extension, the word came to refer to any fluid obtained by distillation, including "alcohol of wine," the distilled essence of wine. Libavius in Alchymia (1594) refers to "vini alcohol vel vinum alcalisatum". Johnson (1657) glosses alcohol vini as "quando omnis superfluitas vini a vino separatur, ita ut accensum ardeat donec totum consumatur, nihilque fæcum aut phlegmatis in fundo remaneat." The word's meaning became restricted to "spirit of wine" (the chemical known today as ethanol) in the 18th century and was extended to the class of substances so-called as "alcohols" in modern chemistry after 1850.[11]

The term ethanol was invented in 1892, blending "ethane" with the "-ol" ending of "alcohol", which was generalized as a libfix.[13]

Systematic names

IUPAC nomenclature is used in scientific publications and where precise identification of the substance is important, especially in cases where the relative complexity of the molecule does not make such a systematic name unwieldy. In naming simple alcohols, the name of the alkane chain loses the terminal e and adds the suffix -ol, e.g., as in "ethanol" from the alkane chain name "ethane".[14] When necessary, the position of the hydroxyl group is indicated by a number between the alkane name and the -ol: propan-1-ol for CH3CH2CH2OH, propan-2-ol for CH3CH(OH)CH3. If a higher priority group is present (such as an aldehyde, ketone, or carboxylic acid), then the prefix hydroxy-is used,[14] e.g., as in 1-hydroxy-2-propanone (CH3C(O)CH2OH).[15]

In cases where the OH functional group is bonded to an sp2 carbon on an aromatic ring the molecule is known as a phenol, and is named using the IUPAC rules for naming phenols.[16]

Common names

In other less formal contexts, an alcohol is often called with the name of the corresponding alkyl group followed by the word "alcohol", e.g., methyl alcohol, ethyl alcohol. Propyl alcohol may be n-propyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol, depending on whether the hydroxyl group is bonded to the end or middle carbon on the straight propane chain. As described under systematic naming, if another group on the molecule takes priority, the alcohol moiety is often indicated using the "hydroxy-" prefix.[17]

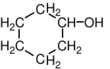

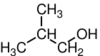

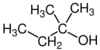

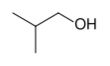

Alcohols are then classified into primary, secondary (sec-, s-), and tertiary (tert-, t-), based upon the number of carbon atoms connected to the carbon atom that bears the hydroxyl functional group. (The respective numeric shorthands 1°, 2°, and 3° are also sometimes used in informal settings.[18]) The primary alcohols have general formulas RCH2OH. The simplest primary alcohol is methanol (CH3OH), for which R=H, and the next is ethanol, for which R=CH3, the methyl group. Secondary alcohols are those of the form RR'CHOH, the simplest of which is 2-propanol (R=R'=CH3). For the tertiary alcohols the general form is RR'R"COH. The simplest example is tert-butanol (2-methylpropan-2-ol), for which each of R, R', and R" is CH3. In these shorthands, R, R', and R" represent substituents, alkyl or other attached, generally organic groups.

In archaic nomenclature, alcohols can be named as derivatives of methanol using "-carbinol" as the ending. For instance, (CH3)3COH can be named trimethylcarbinol.

| Type | Formula | IUPAC Name | Common name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monohydric alcohols |

CH3OH | Methanol | Wood alcohol |

| C2H5OH | Ethanol | Alcohol | |

| C3H7OH | Propan-2-ol | Isopropyl alcohol, Rubbing alcohol | |

| C4H9OH | Butan-1-ol | Butanol, Butyl alcohol | |

| C5H11OH | Pentan-1-ol | Pentanol, Amyl alcohol | |

| C16H33OH | Hexadecan-1-ol | Cetyl alcohol | |

| Polyhydric alcohols |

C2H4(OH)2 | Ethane-1,2-diol | Ethylene glycol |

| C3H6(OH)2 | Propane-1,2-diol | Propylene glycol | |

| C3H5(OH)3 | Propane-1,2,3-triol | Glycerol | |

| C4H6(OH)4 | Butane-1,2,3,4-tetraol | Erythritol, Threitol | |

| C5H7(OH)5 | Pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol | Xylitol | |

| C6H8(OH)6 | hexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol | Mannitol, Sorbitol | |

| C7H9(OH)7 | Heptane-1,2,3,4,5,6,7-heptol | Volemitol | |

| Unsaturated aliphatic alcohols |

C3H5OH | Prop-2-ene-1-ol | Allyl alcohol |

| C10H17OH | 3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-ol | Geraniol | |

| C3H3OH | Prop-2-yn-1-ol | Propargyl alcohol | |

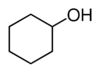

| Alicyclic alcohols |

C6H6(OH)6 | Cyclohexane-1,2,3,4,5,6-hexol | Inositol |

| C10H19OH | 5-Methyl-2-(propan-2-yl)cyclohexan-1-ol | Menthol |

Applications

Alcohols have a long history of myriad uses. For simple mono-alcohols, which is the focus on this article, the following are most important industrial alcohols:[20]

- methanol, mainly for the production of formaldehyde and as a fuel additive

- ethanol, mainly for alcoholic beverages, fuel additive, solvent

- 1-propanol, 1-butanol, and isobutyl alcohol for use as a solvent and precursor to solvents

- C6–C11 alcohols used for plasticizers, e.g. in polyvinylchloride

- fatty alcohol (C12–C18), precursors to detergents

Methanol is the most common industrial alcohol, with about 12 million tons/y produced in 1980. The combined capacity of the other alcohols is about the same, distributed roughly equally.[20]

Toxicity

With respect to acute toxicity, simple alcohols have low acute toxicities. Doses of several milliliters are tolerated. For pentanols, hexanols, octanols and longer alcohols, LD50 range from 2–5 g/kg (rats, oral). Methanol and ethanol are less acutely toxic. All alcohols are mild skin irritants.[20]

The metabolism of methanol (and ethylene glycol) is affected by the presence of ethanol, which has a higher affinity for liver alcohol dehydrogenase. In this way methanol will be excreted intact in urine.[21][22][23]

Physical properties

In general, the hydroxyl group makes alcohols polar. Those groups can form hydrogen bonds to one another and to most other compounds. Owing to the presence of the polar OH alcohols are more water-soluble than simple hydrocarbons. Methanol, ethanol, and propanol are miscible in water. Butanol, with a four-carbon chain, is moderately soluble.

Because of hydrogen bonding, alcohols tend to have higher boiling points than comparable hydrocarbons and ethers. The boiling point of the alcohol ethanol is 78.29 °C, compared to 69 °C for the hydrocarbon hexane, and 34.6 °C for diethyl ether.

Occurrence in nature

Simple alcohols are found widely in nature. Ethanol is the most prominent because it is the product of fermentation, a major energy-producing pathway. The other simple alcohols are formed in only trace amounts. More complex alcohols however are pervasive, as manifested in sugars, some amino acids, and fatty acids.

Production

Ziegler and oxo processes

In the Ziegler process, linear alcohols are produced from ethylene and triethylaluminium followed by oxidation and hydrolysis.[20] An idealized synthesis of 1-octanol is shown:

- Al(C2H5)3 + 9 C2H4 → Al(C8H17)3

- Al(C8H17)3 + 3 O + 3 H2O → 3 HOC8H17 + Al(OH)3

The process generates a range of alcohols that are separated by distillation.

Many higher alcohols are produced by hydroformylation of alkenes followed by hydrogenation. When applied to a terminal alkene, as is common, one typically obtains a linear alcohol:[20]

- RCH=CH2 + H2 + CO → RCH2CH2CHO

- RCH2CH2CHO + 3 H2 → RCH2CH2CH2OH

Such processes give fatty alcohols, which are useful for detergents.

Hydration reactions

Some low molecular weight alcohols of industrial importance are produced by the addition of water to alkenes. Ethanol, isopropanol, 2-butanol, and tert-butanol are produced by this general method. Two implementations are employed, the direct and indirect methods. The direct method avoids the formation of stable intermediates, typically using acid catalysts. In the indirect method, the alkene is converted to the sulfate ester, which is subsequently hydrolyzed. The direct hydration using ethylene (ethylene hydration)[24] or other alkenes from cracking of fractions of distilled crude oil.

Hydration is also used industrially to produce the diol ethylene glycol from ethylene oxide.

Biological routes

Ethanol is obtained by fermentation using glucose produced from sugar from the hydrolysis of starch, in the presence of yeast and temperature of less than 37 °C to produce ethanol. For instance, such a process might proceed by the conversion of sucrose by the enzyme invertase into glucose and fructose, then the conversion of glucose by the enzyme complex zymase into ethanol and carbon dioxide.

Several species of the benign bacteria in the intestine use fermentation as a form of anaerobic metabolism. This metabolic reaction produces ethanol as a waste product. Thus, human bodies contain some quantity of alcohol endogenously produced by these bacteria. In rare cases, this can be sufficient to cause "auto-brewery syndrome" in which intoxicating quantities of alcohol are produced.[25][26][27]

Like ethanol, butanol can be produced by fermentation processes. Saccharomyces yeast are known to produce these higher alcohols at temperatures above 75 °F (24 °C). The bacterium Clostridium acetobutylicum can feed on cellulose to produce butanol on an industrial scale.[28]

Substitution

Primary alkyl halides react with aqueous NaOH or KOH mainly to primary alcohols in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution. (Secondary and especially tertiary alkyl halides will give the elimination (alkene) product instead). Grignard reagents react with carbonyl groups to secondary and tertiary alcohols. Related reactions are the Barbier reaction and the Nozaki-Hiyama reaction.

Reduction

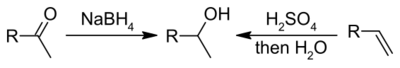

Aldehydes or ketones are reduced with sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride (after an acidic workup). Another reduction by aluminiumisopropylates is the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction. Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation is the asymmetric reduction of β-keto-esters.

Hydrolysis

Alkenes engage in an acid catalysed hydration reaction using concentrated sulfuric acid as a catalyst that gives usually secondary or tertiary alcohols. The hydroboration-oxidation and oxymercuration-reduction of alkenes are more reliable in organic synthesis. Alkenes react with NBS and water in halohydrin formation reaction. Amines can be converted to diazonium salts, which are then hydrolyzed.

The formation of a secondary alcohol via reduction and hydration is shown:

Reactions

Deprotonation

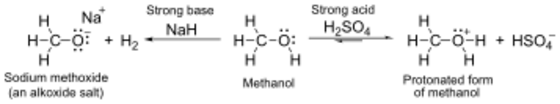

With a pKa of around 16–19, they are, in general, slightly weaker acids than water. With strong bases such as sodium hydride or sodium they form salts called alkoxides, with the general formula RO− M+.

- 2 R-OH + 2 NaH → 2 R-O−Na+ + 2 H2

- 2 R-OH + 2 Na → 2 R-O−Na+ + H2

The acidity of alcohols is strongly affected by solvation. In the gas phase, alcohols are more acidic than in water.[29]

Nucleophilic substitution

The OH group is not a good leaving group in nucleophilic substitution reactions, so neutral alcohols do not react in such reactions. However, if the oxygen is first protonated to give R−OH2+, the leaving group (water) is much more stable, and the nucleophilic substitution can take place. For instance, tertiary alcohols react with hydrochloric acid to produce tertiary alkyl halides, where the hydroxyl group is replaced by a chlorine atom by unimolecular nucleophilic substitution. If primary or secondary alcohols are to be reacted with hydrochloric acid, an activator such as zinc chloride is needed. In alternative fashion, the conversion may be performed directly using thionyl chloride.[1]

Alcohols may, likewise, be converted to alkyl bromides using hydrobromic acid or phosphorus tribromide, for example:

- 3 R-OH + PBr3 → 3 RBr + H3PO3

In the Barton-McCombie deoxygenation an alcohol is deoxygenated to an alkane with tributyltin hydride or a trimethylborane-water complex in a radical substitution reaction.

Dehydration

Meanwhile, the oxygen atom has lone pairs of nonbonded electrons that render it weakly basic in the presence of strong acids such as sulfuric acid. For example, with methanol:

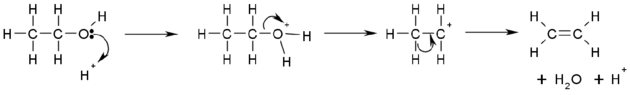

Upon treatment with strong acids, alcohols undergo the E1 elimination reaction to produce alkenes. The reaction, in general, obeys Zaitsev's Rule, which states that the most stable (usually the most substituted) alkene is formed. Tertiary alcohols eliminate easily at just above room temperature, but primary alcohols require a higher temperature.

This is a diagram of acid catalysed dehydration of ethanol to produce ethylene:

A more controlled elimination reaction requires the formation of the xanthate ester.

Protonolysis

Tertiary alcohols react with strong acids to generate carbocations. The reaction is related to their dehydration, e.g. isobutylene from tert-butyl alcohol. A special kind of dehydration reaction involves triphenylmethanol and especially its amine-substituted derivatives. When treated with acid, these alcohols lose water to give stable carbocations, which are commercial dyes.[30] thumb|right|322px|Preparation of crystal violet by protonolysis of the tertiary alcohol.

Esterification

Alcohol and carboxylic acids react in the so-called Fischer esterification. The reaction usually requires a catalyst, such as concentrated sulfuric acid:

- R-OH + R'-CO2H → R'-CO2R + H2O

Other types of ester are prepared in a similar manner – for example, tosyl (tosylate) esters are made by reaction of the alcohol with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in pyridine.

Oxidation

Primary alcohols (R-CH2OH) can be oxidized either to aldehydes (R-CHO) or to carboxylic acids (R-CO2H). The oxidation of secondary alcohols (R1R2CH-OH) normally terminates at the ketone (R1R2C=O) stage. Tertiary alcohols (R1R2R3C-OH) are resistant to oxidation.

The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids normally proceeds via the corresponding aldehyde, which is transformed via an aldehyde hydrate (R-CH(OH)2) by reaction with water before it can be further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.

Reagents useful for the transformation of primary alcohols to aldehydes are normally also suitable for the oxidation of secondary alcohols to ketones. These include Collins reagent and Dess-Martin periodinane. The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids can be carried out using potassium permanganate or the Jones reagent.

See also

- Enol

- Ethanol fuel

- Fatty alcohol

- Index of alcohol-related articles

- List of alcohols

- Lucas test

- Polyol

- Rubbing alcohol

- Sugar alcohol

- Transesterification

Notes

- ↑ "alcohols". IUPAC Gold Book. http://goldbook.iupac.org/A00204.html.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Alcohols". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00204

- ↑ Berthelot, Marcellin; Houdas, Octave V. (1893). La Chimie au Moyen Âge. Vol. I–III. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. vol. I, p. 137.

- ↑ Berthelot & Houdas 1893, vol. I, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2009). "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources from the 8th Century". Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag. pp. 283–298. (same content also available on the author's website).

- ↑ al-Hassan 2009 (same content also available on the author's website); cf. Berthelot & Houdas 1893, vol. I, pp. 141, 143. Sometimes, sulfur was also added to the wine (see Berthelot & Houdas 1893, vol. I, p. 143).

- ↑ Multhauf, Robert P. (1966). The Origins of Chemistry. London: Oldbourne. ISBN 9782881245947. pp. 204-206.

- ↑ Principe, Lawrence M. (2013). The Secrets of Alchemy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226103792. pp. 69-71.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Alcohol". Alcohol. MaoningTech. https://www.etymonline.com/search?q=alcohol. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ Lohninger, H. (21 December 2004). "Etymology of the Word "Alcohol"". VIAS Encyclopedia. http://www.vias.org/encyclopedia/Alcohol_004.html. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "alcohol, n.". alcohol, n.. Oxford University Press. 15 November 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, William (1652). Lexicon Chymicum. https://books.google.com?id=d645AAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Armstrong, Henry E. (8 July 1892). "Contributions to an international system of nomenclature. The nomenclature of cycloids". Proc. Chem. Soc. 8 (114): 128. doi:10.1039/PL8920800127. https://books.google.com/books?id=ax1LAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA128. "As ol is indicative of an OH derivative, there seems no reason why the simple word acid should not connote carboxyl, and why al should not connote COH; the names ethanol ethanal and ethanoic acid or simply ethane acid would then stand for the OH, COH and COOH derivatives of ethane.".

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 William Reusch. "Alcohols". VirtualText of Organic Chemistry. http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/alcohol1.htm#alcnom.

- ↑ Organic chemistry IUPAC nomenclature. Alcohols Rule C-201.

- ↑ Organic Chemistry Nomenclature Rule C-203: Phenols

- ↑ "How to name organic compounds using the IUPAC rules". THE DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS. http://www.chem.uiuc.edu/GenChemReferences/nomenclature_rules.html.

- ↑ Reusch, William (2 October 2013). "Nomenclature of Alcohols". http://chemwiki.ucdavis.edu/Organic_Chemistry/Alcohols/Nomenclature_of_Alcohols.

- ↑ "Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004". https://www.who.int/entity/substance_abuse/publications/global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Falbe, Jürgen; Bahrmann, Helmut; Lipps, Wolfgang; Mayer, Dieter. "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_279..

- ↑ "A seaman with blindness and confusion". BMJ 339: b3929. 30 September 2009. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3929. PMID 19793790. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/339/sep30_1/b3929.

- ↑ Zimmerman, HE; Burkhart, KK; Donovan, JW (1999). "Ethylene glycol and methanol poisoning: diagnosis and treatment". Journal of Emergency Nursing 25 (2): 116–20. doi:10.1016/S0099-1767(99)70156-X. PMID 10097201.

- ↑ Lobert, S (2000). "Ethanol, isopropanol, methanol, and ethylene glycol poisoning". Critical Care Nurse 20 (6): 41–7. doi:10.4037/ccn2000.20.6.41. PMID 11878258.

- ↑ Lodgsdon J.E. (1994). "Ethanol". in Kroschwitz J.I.. Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 9 (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 820. ISBN 978-0-471-52677-3.

- ↑ P. Geertinger MD; J. Bodenhoff; K. Helweg-Larsen; A. Lund (1 September 1982). "Endogenous alcohol production by intestinal fermentation in sudden infant death". Zeitschrift für Rechtsmedizin (Springer-Verlag) 89 (3): 167–172. doi:10.1007/BF01873798. PMID 6760604.

- ↑ "Endogenous ethanol 'auto-brewery syndrome' as a drunk-driving defence challenge". Medicine, Science, and the Law 40 (3): 206–15. July 2000. doi:10.1177/002580240004000304. PMID 10976182.

- ↑ Cecil Adams (20 October 2006). "Designated drunk: Can you get intoxicated without actually drinking alcohol?". The Straight Dope. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2677/designated-drunk.

- ↑ Zverlov, W; Berezina, O; Velikodvorskaya, GA; Schwarz, WH (August 2006). "Bacterial acetone and butanol production by industrial fermentation in the Soviet Union: use of hydrolyzed agricultural waste for biorefinery.". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 71 (5): 587–97. doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0445-z. PMID 16685494.

- ↑ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=JDR-nZpojeEC&printsec=frontcover

- ↑ Gessner, Thomas; Mayer, Udo (2000). "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_179.

References

- Metcalf, Allan A. (1999). The World in So Many Words. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-95920-9.

External links