Astronomy:Binary star

Error: no inner hatnotes detected (help).

A binary star or binary star system is a system of two stars that are gravitationally bound to and in orbit around each other. Binary stars are among the most important objects in astrophysics because they allow direct measurement of stellar masses and test theories of stellar evolution; they also serve as progenitors for phenomena such as novae, type Ia supernovae, and compact object mergers.[1] Binary stars in the night sky that are seen as a single object to the naked eye are often resolved as separate stars using a telescope, in which case they are called visual binaries. Many visual binaries have long orbital periods of several centuries or millennia and therefore have orbits which are uncertain or poorly known. They may also be detected by indirect techniques, such as spectroscopy (spectroscopic binaries) or astrometry (astrometric binaries). If a binary star happens to orbit in a plane along our line of sight, its components will eclipse and transit each other; these pairs are called eclipsing binaries, or, together with other binaries that change brightness as they orbit, photometric binaries.

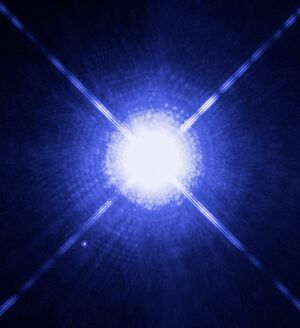

If components in binary star systems are close enough, they can gravitationally distort each other's outer stellar atmospheres. In some cases, these close binary systems can exchange mass, which may bring their evolution to stages that single stars cannot attain. Examples of binaries are Sirius and Cygnus X-1 (Cygnus X-1 being a well-known black hole). Binary stars are also common as the nuclei of many planetary nebulae, and are the progenitors of both novae and type Ia supernovae.[2]

Discovery

Double stars, a pair of stars that appear close to each other, have been observed since the invention of the telescope. Early examples include Mizar and Acrux. Mizar, in the Big Dipper (Ursa Major), was observed to be double by Giovanni Battista Riccioli in 1650[3][4] (and probably earlier by Benedetto Castelli and Galileo).[5] The bright southern star Acrux, in the Southern Cross, was discovered to be double by Father Fontenay in 1685.[3]

Evidence that stars in pairs were more than just optical alignments came in 1767 when English natural philosopher and clergyman John Michell became the first person to apply the mathematics of statistics to the study of the stars, demonstrating in a paper that many more stars occur in pairs or groups than a perfectly random distribution and chance alignment could account for. He focused his investigation on the Pleiades cluster, and calculated that the likelihood of finding such a close grouping of stars was about one in half a million. He concluded that the stars in these double or multiple star systems might be drawn to one another by gravitational pull, thus providing the first evidence for the existence of binary stars and star clusters.[6]

William Herschel began observing double stars in 1779, hoping to find a near star paired with a distant star so he could measure the near star's changing position as the Earth orbited the Sun (measure its parallax), allowing him to calculate the distance to the near star. He would soon publish catalogs of about 700 double stars.[7][8] By 1803, he had observed changes in the relative positions in a number of double stars over the course of 25 years, and concluded that, instead of showing parallax changes, they seemed to be orbiting each other in binary systems.[9] The first orbit of a binary star was computed in 1827, when Félix Savary computed the orbit of Xi Ursae Majoris.[10]

Over the years, many more double stars have been catalogued and measured. As of June 2017, the Washington Double Star Catalog, a database of visual double stars compiled by the United States Naval Observatory, contains over 100,000 pairs of double stars,[11] including optical doubles as well as binary stars. Orbits are known for only a few thousand of these double stars.[12]

Etymology

The term binary was first used in this context by Sir William Herschel in 1802,[13] when he wrote:[14]

If, on the contrary, two stars should really be situated very near each other, and at the same time so far insulated as not to be materially affected by the attractions of neighbouring stars, they will then compose a separate system, and remain united by the bond of their own mutual gravitation towards each other. This should be called a real double star; and any two stars that are thus mutually connected, form the binary sidereal system which we are now to consider.

By the modern definition, the term binary star is generally restricted to pairs of stars which revolve around a common center of mass. Binary stars which can be resolved with a telescope or interferometric methods are known as visual binaries.[15][16] For most of the known visual binary stars one whole revolution has not been observed yet; rather, they are observed to have travelled along a curved path or a partial arc.[17]

The more general term double star is used for pairs of stars which are seen to be close together in the sky.[13] This distinction is rarely made in languages other than English.[15] Double stars may be binary systems or may be merely two stars that appear to be close together in the sky but have vastly different true distances from the Sun. The latter are termed optical doubles or optical pairs.[18]

Classifications

Methods of observation

Binary stars are classified into four types according to the way in which they are observed: visually, by observation; spectroscopically, by periodic changes in spectral lines; photometrically, by changes in brightness caused by an eclipse; or astrometrically, by measuring a deviation in a star's position caused by an unseen companion.[15][19] Any binary star can belong to several of these classes; for example, several spectroscopic binaries are also eclipsing binaries.

Visual binaries

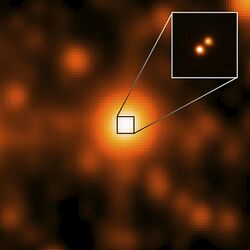

A visual binary star is a binary star for which the angular separation between the two components is great enough to permit them to be observed as a double star in a telescope, or even high-powered binoculars. The angular resolution of the telescope is an important factor in the detection of visual binaries, and as better angular resolutions are applied to binary star observations, an increasing number of visual binaries will be detected. The relative brightness of the two stars is also an important factor, as glare from a bright star may make it difficult to detect the presence of a fainter component.

The brighter star of a visual binary is the primary star, and the dimmer is considered the secondary. In some publications (especially older ones), a faint secondary is called the comes (plural comites; companion). If the stars are the same brightness, the discoverer designation for the primary is customarily accepted.[20]

The position angle of the secondary with respect to the primary is measured, together with the angular distance between the two stars. The time of observation is also recorded. After a sufficient number of observations are recorded over a period of time, they are plotted in polar coordinates with the primary star at the origin, and the most probable ellipse is drawn through these points such that the Keplerian law of areas is satisfied. This ellipse is known as the apparent ellipse, and is the projection of the actual elliptical orbit of the secondary with respect to the primary on the plane of the sky. From this projected ellipse the complete elements of the orbit may be computed, where the semi-major axis can only be expressed in angular units unless the stellar parallax, and hence the distance, of the system is known.[16]

Spectroscopic binaries

Sometimes, the only evidence of a binary star comes from the Doppler effect on its emitted light. In these cases, the binary consists of a pair of stars where the spectral lines in the light emitted from each star first shifts towards the blue, when the star is moving towards us, and towards the red, when it is moving away from us, during its motion about their common center of mass, with the period of their common orbit.

In these systems, the separation between the stars is usually very small, and the orbital velocity very high. Unless the plane of the orbit happens to be perpendicular to the line of sight, the orbital velocities have components in the line of sight, and the observed radial velocity of the system varies periodically. Since radial velocity can be measured with a spectrometer by observing the Doppler shift of the stars' spectral lines, the binaries detected in this manner are known as spectroscopic binaries. Most of these cannot be resolved as a visual binary, even with telescopes of the highest existing resolving power.

In some spectroscopic binaries, spectral lines from both stars are visible, and the lines are alternately double and single. Such a system is known as a double-lined spectroscopic binary (often denoted "SB2"). In other systems, the spectrum of only one of the stars is seen, and the lines in the spectrum shift periodically towards the blue, then towards red and back again. Such stars are known as single-lined spectroscopic binaries ("SB1").

The orbit of a spectroscopic binary is determined by making a long series of observations of the radial velocity of one or both components of the system. The observations are plotted against time, and from the resulting curve a period is determined. If the orbit is circular, then the curve is a sine curve. If the orbit is elliptical, the shape of the curve depends on the eccentricity of the ellipse and the orientation of the major axis with reference to the line of sight.

It is impossible to determine individually the semi-major axis a and the inclination of the orbit plane i. However, the product of the semi-major axis and the sine of the inclination (i.e. a sin i) may be determined directly in linear units (e.g. kilometres). If either a or i can be determined by other means, as in the case of eclipsing binaries, a complete solution for the orbit can be found.[21]

Binary stars that are both visual and spectroscopic binaries are rare and are a valuable source of information when found. About 40 are known. Visual binary stars often have large true separations, with periods measured in decades to centuries; consequently, they usually have orbital speeds too small to be measured spectroscopically. Conversely, spectroscopic binary stars move fast in their orbits because they are close together, usually too close to be detected as visual binaries. Binaries that are found to be both visual and spectroscopic thus must be relatively close to Earth.

Eclipsing binaries

An eclipsing binary star is a binary star system in which the orbital plane of the two stars lies so nearly in the line of sight of the observer that the components undergo mutual eclipses.[22] In the case where the binary is also a spectroscopic binary and the parallax of the system is known, the binary is quite valuable for stellar analysis. Algol, a triple star system in the constellation Perseus, contains the best-known example of an eclipsing binary.

File:Artist’s impression of eclipsing binary.ogv Eclipsing binaries are variable stars, not because the light of the individual components vary but because of the eclipses. The light curve of an eclipsing binary is characterized by periods of practically constant light, with periodic drops in intensity when one star passes in front of the other. The brightness may drop twice during the orbit, once when the secondary passes in front of the primary and once when the primary passes in front of the secondary. The deeper of the two eclipses is called the primary regardless of which star is being occulted, and if a shallow second eclipse also occurs it is called the secondary eclipse. The size of the brightness drops depends on the relative brightness of the two stars, the proportion of the occulted star that is hidden, and the surface brightness (i.e. effective temperature) of the stars. Typically the occultation of the hotter star causes the primary eclipse.[22]

An eclipsing binary's period of orbit may be determined from a study of its light curve, and the relative sizes of the individual stars can be determined in terms of the radius of the orbit, by observing how quickly the brightness changes as the disc of the nearest star slides over the disc of the other star.[22] If it is also a spectroscopic binary, the orbital elements can also be determined, and the mass of the stars can be determined relatively easily, which means that the relative densities of the stars can be determined in this case.[23]

Since about 1995, measurement of extragalactic eclipsing binaries' fundamental parameters has become possible with 8-meter class telescopes. This makes it feasible to use them to directly measure the distances to external galaxies, a process that is more accurate than using standard candles.[24] By 2006, they had been used to give direct distance estimates to the LMC, SMC, Andromeda Galaxy, and Triangulum Galaxy. Eclipsing binaries offer a direct method to gauge the distance to galaxies to an improved 5% level of accuracy.[25]

Non-eclipsing binaries that can be detected through photometry

Nearby non-eclipsing binaries can also be photometrically detected by observing how the stars affect each other in three ways. The first is by observing extra light which the stars reflect from their companion. Second is by observing ellipsoidal light variations which are caused by deformation of the star's shape by their companions. The third method is by looking at how relativistic beaming affects the apparent magnitude of the stars. Detecting binaries with these methods requires accurate photometry.[26]

Astrometric binaries

Astronomers have discovered some stars that seemingly orbit around an empty space. Astrometric binaries are relatively nearby stars which can be seen to wobble around a point in space, with no visible companion. The same mathematics used for ordinary binaries can be applied to infer the mass of the missing companion. The companion could be very dim, so that it is currently undetectable or masked by the glare of its primary, or it could be an object that emits little or no electromagnetic radiation, for example a neutron star.[27]

The visible star's position is carefully measured and detected to vary, due to the gravitational influence from its counterpart. The position of the star is repeatedly measured relative to more distant stars, and then checked for periodic shifts in position. Typically this type of measurement can only be performed on nearby stars, such as those within 10 parsecs. Nearby stars often have a relatively high proper motion, so astrometric binaries will appear to follow a wobbly path across the sky.

If the companion is sufficiently massive to cause an observable shift in position of the star, then its presence can be deduced. From precise astrometric measurements of the movement of the visible star over a sufficiently long period of time, information about the mass of the companion and its orbital period can be determined.[28] Even though the companion is not visible, the characteristics of the system can be determined from the observations using Kepler's laws.[29]

This method of detecting binaries is also used to locate extrasolar planets orbiting a star. However, the requirements to perform this measurement are very exacting, due to the great difference in the mass ratio, and the typically long period of the planet's orbit. Detection of position shifts of a star is a very exacting science, and it is difficult to achieve the necessary precision. Space telescopes can avoid the blurring effect of Earth's atmosphere, resulting in more precise resolution.

Configuration of the system

Another classification is based on the distance between the stars, relative to their sizes:[30]

Detached binaries are binary stars where each component is within its Roche lobe, i.e. the area where the gravitational pull of the star itself is larger than that of the other component. While on the main sequence the stars have no major effect on each other, and essentially evolve separately. Most binaries belong to this class.

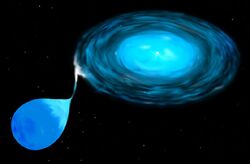

Semidetached binary stars are binary stars where one of the components fills the binary star's Roche lobe and the other does not. In this interacting binary star, gas from the surface of the Roche-lobe-filling component (donor) is transferred to the other, accreting star. The mass transfer dominates the evolution of the system. In many cases, the inflowing gas forms an accretion disc around the accretor.

A contact binary is a type of binary star in which both components of the binary fill their Roche lobes. The uppermost part of the stellar atmospheres forms a common envelope that surrounds both stars. As the friction of the envelope brakes the orbital motion, the stars may eventually merge.[31] W Ursae Majoris is an example.

Cataclysmic variables and X-ray binaries

When a binary system contains a compact object such as a white dwarf, neutron star or black hole, gas from the other (donor) star can accrete onto the compact object. This releases gravitational potential energy, causing the gas to become hotter and emit radiation. Cataclysmic variable stars, where the compact object is a white dwarf, are examples of such systems.[32] In X-ray binaries, the compact object can be either a neutron star or a black hole. These binaries are classified as low-mass or high-mass according to the mass of the donor star. High-mass X-ray binaries contain a young, early-type, high-mass donor star which transfers mass by its stellar wind, while low-mass X-ray binaries are semidetached binaries in which gas from a late-type donor star or a white dwarf overflows the Roche lobe and falls towards the neutron star or black hole.[33] Probably the best known example of an X-ray binary is the high-mass X-ray binary Cygnus X-1. In Cygnus X-1, the mass of the unseen companion is estimated to be about nine times that of the Sun,[34] far exceeding the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit for the maximum theoretical mass of a neutron star. It is therefore believed to be a black hole; it was the first object for which this was widely believed.[35]

Orbital period

Orbital periods can be less than an hour (for AM CVn stars), or a few days (components of Beta Lyrae), but also hundreds of thousands of years (Proxima Centauri around Alpha Centauri AB).

Variations in period

The Applegate mechanism explains long term orbital period variations seen in certain eclipsing binaries. As a main-sequence star goes through an activity cycle, the outer layers of the star are subject to a magnetic torque changing the distribution of angular momentum, resulting in a change in the star's oblateness. The orbit of the stars in the binary pair is gravitationally coupled to their shape changes, so that the period shows modulations (typically on the order of ∆P/P ~ 10−5) on the same time scale as the activity cycles (typically on the order of decades).[36]

Another phenomenon observed in some Algol binaries has been monotonic period increases. This is quite distinct from the far more common observations of alternating period increases and decreases explained by the Applegate mechanism. Monotonic period increases have been attributed to mass transfer, usually (but not always) from the less massive to the more massive star[37]

Designations

A and B

The components of binary stars are denoted by the suffixes A and B appended to the system's designation, A denoting the primary and B the secondary. The suffix AB may be used to denote the pair (for example, the binary star α Centauri AB consists of the stars α Centauri A and α Centauri B.) Additional letters, such as C, D, etc., may be used for systems with more than two stars.[38] In cases where the binary star has a Bayer designation and is widely separated, it is possible that the members of the pair will be designated with superscripts; an example is Zeta Reticuli, whose components are ζ1 Reticuli and ζ2 Reticuli.[39]

Discoverer designations

Double stars are also designated by an abbreviation giving the discoverer together with an index number.[40] α Centauri, for example, was found to be double by Father Richaud in 1689, and so is designated RHD 1.[3][41] These discoverer codes can be found in the Washington Double Star Catalog.[42]

Hot and cold

The secondary star in a binary star system may be designated as the hot companion or cool companion, depending on its temperature relative to the primary star.

Examples:

- Antares (Alpha Scorpii) is a red supergiant star in a binary system with a hotter blue main-sequence star Antares B. Antares B can therefore be termed a hot companion of the cool supergiant.[43]

- Symbiotic stars, such as R Aquarii, are binary star systems composed of a late-type giant star and a hotter companion object. Since the nature of the companion is not well-established in all cases, it may be termed a "hot companion".[44]

- The luminous blue variable Eta Carinae has been determined to be a binary star system. The secondary appears to have a higher temperature than the primary and has therefore been described as being the "hot companion" star. It may be a Wolf–Rayet star.[45]

- NASA's Kepler mission has discovered examples of eclipsing binary stars where the secondary is the hotter component. KOI-74b is a 12,000 K white dwarf companion of KOI-74 (KIC 6889235), a 9,400 K early A-type main-sequence star.[46][47][48] KOI-81b is a 13,000 K white dwarf companion of KOI-81 (KIC 8823868), a 10,000 K late B-type main-sequence star.[46][47][48]

Evolution

Formation

While it is not impossible that some binaries might be created through gravitational capture between two single stars, given the very low likelihood of such an event (three objects being actually required, as conservation of energy rules out a single gravitating body capturing another) and the high number of binaries currently in existence, this cannot be the primary formation process. The observation of binaries consisting of stars not yet on the main sequence supports the theory that binaries develop during star formation. Fragmentation of the molecular cloud during the formation of protostars is an acceptable explanation for the formation of a binary or multiple star system.[49][50]

The outcome of the three-body problem, in which the three stars are of comparable mass, is that eventually one of the three stars will be ejected from the system and, assuming no significant further perturbations, the remaining two will form a stable binary system.

Mass transfer and accretion

File:Artist's impression of the evolution of a hot high-mass binary star.ogv

As a main-sequence star increases in size during its evolution, it may at some point exceed its Roche lobe, meaning that some of its matter ventures into a region where the gravitational pull of its companion star is larger than its own.[51] The result is that matter will transfer from one star to another through a process known as Roche lobe overflow (RLOF), either being absorbed by direct impact or through an accretion disc. The mathematical point through which this transfer happens is called the first Lagrangian point.[52] It is not uncommon that the accretion disc is the brightest (and thus sometimes the only visible) element of a binary star.

If a star grows outside of its Roche lobe too fast for all abundant matter to be transferred to the other component, it is also possible that matter will leave the system through other Lagrange points or as stellar wind, thus being effectively lost to both components.[53] Since the evolution of a star is determined by its mass, the process influences the evolution of both companions, and creates stages that cannot be attained by single stars.[54][55][56]

Studies of the eclipsing ternary Algol led to the Algol paradox in the theory of stellar evolution: although components of a binary star form at the same time, and massive stars evolve much faster than the less massive ones, it was observed that the more massive component Algol A is still in the main sequence, while the less massive Algol B is a subgiant at a later evolutionary stage. The paradox can be solved by mass transfer: when the more massive star became a subgiant, it filled its Roche lobe, and most of the mass was transferred to the other star, which is still in the main sequence. In some binaries similar to Algol, a gas flow can actually be seen.[57]

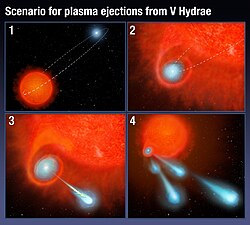

Runaways and novae

It is also possible for widely separated binaries to lose gravitational contact with each other during their lifetime, as a result of external perturbations. The components will then move on to evolve as single stars. A close encounter between two binary systems can also result in the gravitational disruption of both systems, with some of the stars being ejected at high velocities, leading to runaway stars.[58]

If a white dwarf has a close companion star that overflows its Roche lobe, the white dwarf will steadily accrete gases from the star's outer atmosphere. These are compacted on the white dwarf's surface by its intense gravity, compressed and heated to very high temperatures as additional material is drawn in. The white dwarf consists of degenerate matter and so is largely unresponsive to heat, while the accreted hydrogen is not. Hydrogen fusion can occur in a stable manner on the surface through the CNO cycle, causing the enormous amount of energy liberated by this process to blow the remaining gases away from the white dwarf's surface. The result is an extremely bright outburst of light, known as a nova.[59]

In extreme cases this event can cause the white dwarf to exceed the Chandrasekhar limit and trigger a supernova that destroys the entire star, another possible cause for runaways.[60][61] An example of such an event is the supernova SN 1572, which was observed by Tycho Brahe. The Hubble Space Telescope recently[when?] took a picture of the remnants of this event.

Astrophysics

Astrophysical importance

Binary star systems are critical laboratories for measuring fundamental stellar properties because the orbital dynamics allow determination of the masses and radii of stars with high precision. They also play key roles in the production of exotic objects such as neutron star binaries and black hole binaries, which are sources of gravitational waves.[62]

Binaries provide the best method for astronomers to determine the mass of a distant star. The gravitational pull between them causes them to orbit around their common center of mass. From the orbital pattern of a visual binary, or the time variation of the spectrum of a spectroscopic binary, the mass of its stars can be determined, for example with the binary mass function. In this way, the relation between a star's appearance (temperature and radius) and its mass can be found, which allows for the determination of the mass of non-binaries.

Because a large proportion of stars exist in binary systems, binaries are particularly important to our understanding of the processes by which stars form. In particular, the period and masses of the binary tell us about the amount of angular momentum in the system. Because this is a conserved quantity in physics, binaries give us important clues about the conditions under which the stars were formed.

Calculating the center of mass in binary stars

In a simple binary case, the distance r1 from the center of the first star to the center of mass or barycenter is given by

where

- a is the distance between the two stellar centers, and

- m1 and m2 are the masses of the two stars.

If a is taken to be the semimajor axis of the orbit of one body around the other, then r1 is the semimajor axis of the first body's orbit around the center of mass or barycenter, and r2 = a − r1 is the semimajor axis of the second body's orbit. When the center of mass is located within the more massive body, that body appears to wobble rather than following a discernible orbit.

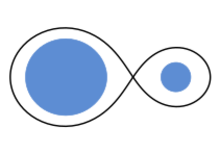

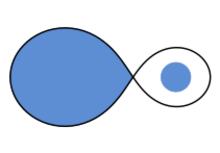

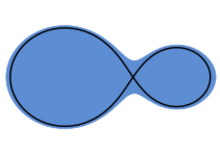

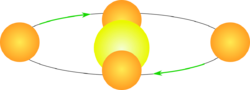

Center-of-mass animations

The red cross marks the center of mass of the system. These images do not represent any specific real system.

| 160px (a) Two bodies of similar mass orbiting around a common center of mass, or barycenter |

160px (b) Two bodies with a difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter, like the Charon–Pluto system |

| 160px (c) Two bodies with a major difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter (similar to the Earth–Moon system) |

160px (d) Two bodies with an extreme difference in mass orbiting around a common barycenter (similar to the Sun–Earth system) |

| 320px (e) Two bodies with similar mass orbiting in an ellipse around a common barycenter | |

Research findings

| Mass range | Multiplicity frequency |

Average companions |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0.1 M☉ | 22%+6% −4% |

0.22+0.06 −0.04 |

| 0.1–0.5 M☉ | 26%±3% | 0.33±0.05 |

| 0.7–1.3 M☉ | 44%±2% | 0.62±0.03 |

| 1.5–5 M☉ | ≥ 50% | 1.00±0.10 |

| 8–16 M☉ | ≥ 60% | 1.00±0.20 |

| ≥ 16 M☉ | ≥ 80% | 1.30±0.20 |

It is estimated that approximately one third of the star systems in the Milky Way are binary or multiple, with the remaining two thirds being single stars.[64] The overall multiplicity frequency of ordinary stars is a monotonically increasing function of stellar mass. That is, the likelihood of being in a binary or a multi-star system steadily increases as the masses of the components increase.[63]

There is a direct correlation between the period of revolution of a binary star and the eccentricity of its orbit, with systems of short period having smaller eccentricity. Binary stars may be found with any conceivable separation, from pairs orbiting so closely that they are practically in contact with each other, to pairs so distantly separated that their connection is indicated only by their common proper motion through space. Among gravitationally bound binary star systems, there exists a so-called log normal distribution of periods, with the majority of these systems orbiting with a period of about 100 years. This is supporting evidence for the theory that binary systems are formed during star formation.[65]

In pairs where the two stars are of equal brightness, they are also of the same spectral type. In systems where the brightnesses are different, the fainter star is bluer if the brighter star is a giant star, and redder if the brighter star belongs to the main sequence.[66]

The mass of a star can be directly determined only from its gravitational attraction. Apart from the Sun and stars which act as gravitational lenses, this can be done only in binary and multiple star systems, making the binary stars an important class of stars. In the case of a visual binary star, after the orbit and the stellar parallax of the system has been determined, the combined mass of the two stars may be obtained by a direct application of the Keplerian harmonic law.[67]

Unfortunately, it is impossible to obtain the complete orbit of a spectroscopic binary unless it is also a visual or an eclipsing binary, so from these objects only a determination of the joint product of mass and the sine of the angle of inclination relative to the line of sight is possible. In the case of eclipsing binaries which are also spectroscopic binaries, it is possible to find a complete solution for the specifications (mass, density, size, luminosity, and approximate shape) of both members of the system.

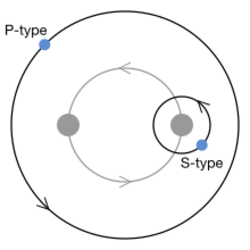

Planets

While a number of binary star systems have been found to harbor extrasolar planets, such systems are comparatively rare compared to single star systems. Observations by the Kepler space telescope have shown that most single stars of the same type as the Sun have plenty of planets, but only one-third of binary stars do. According to theoretical simulations,[68] even widely separated binary stars often disrupt the discs of rocky grains from which protoplanets form. On the other hand, other simulations suggest that the presence of a binary companion can actually improve the rate of planet formation within stable orbital zones by "stirring up" the protoplanetary disk, increasing the accretion rate of the protoplanets within.[69]

Detecting planets in multiple star systems introduces additional technical difficulties, which may be why they are only rarely found.[70] Examples include the white dwarf-pulsar binary PSR B1620-26, the subgiant-red dwarf binary Gamma Cephei, and the white dwarf-red dwarf binary NN Serpentis, among others.[71]

A study of fourteen previously known planetary systems found three of these systems to be binary systems. All planets were found to be in S-type orbits around the primary star. In these three cases the secondary star was much dimmer than the primary and so was not previously detected. This discovery resulted in a recalculation of parameters for both the planet and the primary star.[72]

Science fiction has often featured planets of binary or ternary stars as a setting, for example, George Lucas' Tatooine from Star Wars, and one notable story, "Nightfall", even takes this to a six-star system. In reality, some orbital ranges are impossible for dynamical reasons (the planet would be expelled from its orbit relatively quickly, being either ejected from the system altogether or transferred to a more inner or outer orbital range), whilst other orbits present serious challenges for eventual biospheres because of likely extreme variations in surface temperature during different parts of the orbit. Planets that orbit just one star in a binary system are said to have "S-type" orbits, whereas those that orbit around both stars have "P-type" or "circumbinary" orbits. It is estimated that 50–60% of binary systems are capable of supporting habitable terrestrial planets within stable orbital ranges.[69]

Examples

The large distance between the components, as well as their difference in color, make Albireo one of the easiest observable visual binaries. The brightest member, which is the third-brightest star in the constellation Cygnus, is actually a close binary itself. Also in the Cygnus constellation is Cygnus X-1, an X-ray source considered to be a black hole. It is a high-mass X-ray binary, with the optical counterpart being a variable star.[73] Sirius is another binary and the brightest star in the night time sky, with a visual apparent magnitude of −1.46. It is located in the constellation Canis Major. In 1844 Friedrich Bessel deduced that Sirius was a binary. In 1862 Alvan Graham Clark discovered the companion (Sirius B; the visible star is Sirius A). In 1915 astronomers at the Mount Wilson Observatory determined that Sirius B was a white dwarf, the first to be discovered. In 2005, using the Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers determined Sirius B to be 12,000 km (7,456 mi) in diameter, with a mass that is 98% of the Sun.[74]

An example of an eclipsing binary is Epsilon Aurigae in the constellation Auriga. The visible component belongs to the spectral class F0, the other (eclipsing) component is not visible. The last such eclipse occurred from 2009 to 2011, and it is hoped that the extensive observations that will likely be carried out may yield further insights into the nature of this system. Another eclipsing binary is Beta Lyrae, which is a semidetached binary star system in the constellation of Lyra.

Other interesting binaries include 61 Cygni (a binary in the constellation Cygnus, composed of two K class (orange) main-sequence stars, 61 Cygni A and 61 Cygni B, which is known for its large proper motion), Procyon (the brightest star in the constellation Canis Minor and the eighth-brightest star in the night time sky, which is a binary consisting of the main star with a faint white dwarf companion), SS Lacertae (an eclipsing binary which stopped eclipsing), V907 Sco (an eclipsing binary which stopped, restarted, then stopped again), BG Geminorum (an eclipsing binary which is thought to contain a black hole with a K0 star in orbit around it), and 2MASS J18082002−5104378 (a binary in the "thin disk" of the Milky Way, and containing one of the oldest known stars).[75]

Multiple-star examples

Systems with more than two stars are termed multiple stars. Algol is the most noted ternary (long thought to be a binary), located in the constellation Perseus. Two components of the system eclipse each other, the variation in the intensity of Algol first being recorded in 1670 by Geminiano Montanari. The name Algol means "demon star" (from Arabic: الغول al-ghūl), which was probably given due to its peculiar behavior. Another visible ternary is Alpha Centauri, in the southern constellation of Centaurus, which contains the third-brightest star in the night sky, with an apparent visual magnitude of −0.01. This system also underscores the fact that no search for habitable planets is complete if binaries are discounted. Alpha Centauri A and B have an 11 AU distance at closest approach, and both should have stable habitable zones.[76]

There are also examples of systems beyond ternaries: Castor is a sextuple star system, which is the second-brightest star in the constellation Gemini and one of the brightest stars in the nighttime sky. Astronomically, Castor was discovered to be a visual binary in 1719. Each of the components of Castor is itself a spectroscopic binary. Castor also has a faint and widely separated companion, which is also a spectroscopic binary. The Alcor–Mizar visual binary in Ursa Majoris also consists of six stars: four comprising Mizar and two comprising Alcor. QZ Carinae is a complex multiple star system made up of at least nine individual stars.[77]

See also

- 104 Aquarii, possible binary

- 107 Aquarii, "double star", about 240 light-years from Earth

- Beta Centauri

- Binary black hole

- Binary brown dwarfs

- Circumbinary planet

- Habitability of binary star systems

- HD 30453, a spectroscopic binary with a 3rd component

- Hills mechanism

- Heartbeat star, a type of binary star system

- Rotational Brownian motion

- Two-body problem in general relativity

- HM Cancri, an ultra-compact binary white dwarf system with an orbital period of about 5.4 minutes

- Eta Cassiopeiae, a nearby visual binary star system in the constellation Cassiopeia

- Kepler-14, a binary star system known to host an exoplanet

Notes and references

- ↑ "Understanding Binary Stars and Their Importance". Simple Science. https://scisimple.com/en/articles/2025-08-17-understanding-binary-stars-and-their-importance--a9n8xxp.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedimportance2 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 The Binary Stars, Robert Grant Aitken, New York: Dover, 1964, p. 1.

- ↑ Vol. 1, part 1, p. 422, Almagestum Novum, Giovanni Battista Riccioli, Bononiae: Ex typographia haeredis Victorij Benatij, 1651.

- ↑ A New View of Mizar , Leos Ondra, accessed on line May 26, 2007.

- ↑ This Month in Physics History, November 27, 1783: John Michell anticipates black holes, APS News, November 2009 (Volume 18, Number 10), www.aps.org

- ↑ Aitken, Robert Grant (1935). The Binary Stars. New York and London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc.. pp. 4–9. ISBN 978-1117504094. https://archive.org/stream/binarystars00aitk#page/4/mode/2up.

- ↑ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 4. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4. https://archive.org/details/DoubleStars/page/4.

- ↑ Herschel, William (1803). "Account of the Changes That Have Happened, during the Last Twenty-Five Years, in the Relative Situation of Double-Stars; with an Investigation of the Cause to Which They Are Owing". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 93: 339–382. doi:10.1098/rstl.1803.0015.

- ↑ p. 291, French astronomers, visual double stars and the double stars working group of the Société Astronomique de France, E. Soulié, The Third Pacific Rim Conference on Recent Development of Binary Star Research, proceedings of a conference sponsored by Chiang Mai University, Thai Astronomical Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln held in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 26 October-1 November 1995, ASP Conference Series 130 (1997), ed. Kam-Ching Leung, pp. 291–294, Bibcode: 1997ASPC..130..291S.

- ↑ "Introduction and Growth of the WDS", The Washington Double Star Catalog , Brian D. Mason, Gary L. Wycoff, and William I. Hartkopf, Astrometry Department, United States Naval Observatory, accessed on line August 20, 2008.

- ↑ Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars , William I. Hartkopf and Brian D. Mason, United States Naval Observatory, accessed on line August 20, 2008.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 The Binary Stars, Robert Grant Aitken, New York: Dover, 1964, p. ix.

- ↑ Herschel, William (1802). "Catalogue of 500 New Nebulae, Nebulous Stars, Planetary Nebulae, and Clusters of Stars; With Remarks on the Construction of the Heavens". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 92: 477–528 [481]. doi:10.1098/rstl.1802.0021. Bibcode: 1802RSPT...92..477H. https://zenodo.org/record/1432308.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4. https://archive.org/details/DoubleStars/page/1.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Visual Binaries". University of Tennessee. http://csep10.phys.utk.edu/astr162/lect/binaries/visual.html.

- ↑ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4. https://archive.org/details/DoubleStars/page/5.

- ↑ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4. https://archive.org/details/DoubleStars/page/17.

- ↑ "Binary Stars". Cornell University. https://astrosun2.astro.cornell.edu/academics/courses/astro201/binstar.htm.

- ↑ Aitken, R.G. (1964). The Binary Stars. New York: Dover. p. 41.

- ↑ Herter, T.. "Stellar Masses". Cornell University. https://www.astro.cornell.edu/academics/courses/astro101/lectures/lec16.htm.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Bruton, D.. "Eclipsing Binary Stars". Stephen F. Austin State University. http://www.physics.sfasu.edu/astro/ebstar/ebstar.html.

- ↑ Worth, M. "Binary Stars" (PowerPoint). Stephen F. Austin State University. http://www.physics.sfasu.edu/markworth/ast105/Binary-Stars.ppt.

- ↑ Wilson, R.E. (1 January 2008). "Eclipsing binary solutions in physical units and direct distance estimation". The Astrophysical Journal 672 (1): 575–589. doi:10.1086/523634. Bibcode: 2008ApJ...672..575W.

- ↑ Bonanos, Alceste Z. (2006). "Eclipsing binaries: Tools for calibrating the extragalactic distance scale". Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 2: 79–87. doi:10.1017/S1743921307003845. Bibcode: 2007IAUS..240...79B.

- ↑ Tal-Or, Lev; Faigler, Simchon; Mazeh, Tsevi (2014). "Seventy-two new non-eclipsing BEER binaries discovered in CoRoT lightcurves and confirmed by RVs from AAOmega". EPJ Web of Conferences 101: 06063. doi:10.1051/epjconf/201510106063.

- ↑ Bock, D.. "Binary neutron star collision". University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. http://lantern.ncsa.uiuc.edu/~dbock/Vis/NeutronStar/Summary.html.

- ↑ Asada, H.; Akasaka, T.; Kasai, M. (27 September 2004). "Inversion formula for determining parameters of an astrometric binary". Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 56 (6): L35–L38. doi:10.1093/pasj/56.6.L35. Bibcode: 2004PASJ...56L..35A.

- ↑ "Astrometric Binaries". University of Tennessee. http://csep10.phys.utk.edu/astr162/lect/binaries/astrometric.html.

- ↑ Nguyen, Q.. "Roche model". San Diego State University. http://mintaka.sdsu.edu/faculty/quyen/node10.html.

- ↑ Voss, R.; Tauris, T.M. (2003). "Galactic distribution of merging neutron stars and black holes". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 342 (4): 1169–1184. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06616.x. Bibcode: 2003MNRAS.342.1169V.

- ↑ Smith, Robert Connon (November 2006). "Cataclysmic Variables". Contemporary Physics 47 (6): 363–386. doi:10.1080/00107510601181175. Bibcode: 2007astro.ph..1654S. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/2256/1/cp06_12-15_cvreview.pdf.

- ↑ Israel, Gian Luca (October 1996). "Neutron Star X-ray binaries". A Systematic Search of New X-ray Pulsators in ROSAT Fields (Ph.D. thesis). Trieste. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008.

- ↑ Iorio, Lorenzo (2008). "On the orbital and physical parameters of the HDE 226868 / Cygnus X-1 binary system". Astrophysics and Space Science 315 (1–4): 335–340. doi:10.1007/s10509-008-9839-y. Bibcode: 2008Ap&SS.315..335I.

- ↑ "Black Holes". NASA. http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l2/black_holes.html.

- ↑ Applegate, James H. (1992). "A mechanism for orbital period modulation in close binaries". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1 385: 621–629. doi:10.1086/170967. Bibcode: 1992ApJ...385..621A.

- ↑ Hall, Douglas S. (1989). "The relation between RS CVn and Algol". Space Science Reviews 50 (1–2): 219–233. doi:10.1007/BF00215932. Bibcode: 1989SSRv...50..219H.

- ↑ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4. https://archive.org/details/DoubleStars/page/19.

- ↑ "Binary and Multiple Star Systems". Lawrence Hall of Science at the University of California. http://sunra.lbl.gov/~vhoette/Explorations/BinaryStars/.

- ↑ pp. 307–308, Observing and Measuring Double Stars, Bob Argyle, ed., London: Springer, 2004, ISBN 1-85233-558-0.

- ↑ Entry 14396-6050, discoverer code RHD 1AB,The Washington Double Star Catalog , United States Naval Observatory. Accessed on line August 20, 2008.

- ↑ References and discoverer codes, The Washington Double Star Catalog , United States Naval Observatory. Accessed on line August 20, 2008.

- ↑ [1] – see essential notes: "Hot companion to Antares at 2.9arcsec; estimated period: 678yr."

- ↑ Kenyon, S. J.; Webbink, R. F. (1984). "The nature of symbiotic stars". Astrophysical Journal 279: 252–283. doi:10.1086/161888. Bibcode: 1984ApJ...279..252K.

- ↑ Iping, Rosina C.; Sonneborn, George; Gull, Theodore R.; Massa, Derck L.; Hillier, D. John (2005). "Detection of a Hot Binary Companion of η Carinae". The Astrophysical Journal 633 (1): L37–L40. doi:10.1086/498268. Bibcode: 2005ApJ...633L..37I.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Rowe, Jason F.; Borucki, William J.; Koch, David; Howell, Steve B.; Basri, Gibor; Batalha, Natalie; Brown, Timothy M.; Caldwell, Douglas et al. (2010). "Kepler Observations of Transiting Hot Compact Objects". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 713 (2): L150–L154. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/713/2/L150. Bibcode: 2010ApJ...713L.150R.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 van Kerkwijk, Marten H.; Rappaport, Saul A.; Breton, René P.; Justham, Stephen; Podsiadlowski, Philipp; Han, Zhanwen (2010). "Observations of Doppler Boosting in Kepler Light Curves". The Astrophysical Journal 715 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/715/1/51. Bibcode: 2010ApJ...715...51V.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Borenstein, Seth (4 January 2010). "Planet-hunting telescope unearths hot mysteries". https://www.usnews.com/science/articles/2010/01/05/planet-hunting-telescope-unearths-hot-mysteries.

- ↑ Boss, A. P. (1992). "Formation of Binary Stars". in J. Sahade. The Realm of Interacting Binary Stars. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-7923-1675-6.

- ↑ Tohline, J. E.; J. E. Cazes. "The Formation of Common-Envelope, Pre-Main-Sequence Binary Stars". Louisiana State University. http://www.phys.lsu.edu/astro/nap98/bf.final.html.

- ↑ Kopal, Z. (1989). The Roche Problem. Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-0-7923-0129-5.

- ↑ "Contact Binary Star Envelopes" by Jeff Bryant, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- ↑ "Mass Transfer in Binary Star Systems" by Jeff Bryant with Waylena McCully, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- ↑ Boyle, C.B. (1984). "Mass transfer and accretion in close binaries – A review". Vistas in Astronomy 27 (2): 149–169. doi:10.1016/0083-6656(84)90007-2. Bibcode: 1984VA.....27..149B.

- ↑ Vanbeveren, D.; W. van Rensbergen; C. de Loore (2001). The Brightest Binaries. Springer. ISBN 978-0-7923-5155-9.

- ↑ Chen, Z; A. Frank; E. G. Blackman; J. Nordhaus; J. Carroll-Nellenback (2017). "Mass Transfer and Disc Formation in AGB Binary Systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 468 (4): 4465–4477. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx680. Bibcode: 2017MNRAS.468.4465C.

- ↑ Blondin, J. M.; M. T. Richards. "Mass Transfer in the Binary Star Algol". American Museum of Natural History. http://www.haydenplanetarium.org/hp/vo/ava/avapages/S1200algolbpi.html.

- ↑ Hoogerwerf, R.; de Bruijne, J.H.J.; de Zeeuw, P.T. (December 2000). "The Origin of Runaway Stars". Astrophysical Journal 544 (2): L133. doi:10.1086/317315. Bibcode: 2000ApJ...544L.133H.

- ↑ Prialnik, D. (2001). "Novae". Encyclopaedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics. pp. 1846–1856.

- ↑ Icko, I. (1986). "Binary Star Evolution and Type I Supernovae". Cosmogonical Processes. p. 155.

- ↑ Fender, R. (2002). "Relativistic Outflows from X-ray Binaries ('Microquasars')". Relativistic Flows in Astrophysics. Lecture Notes in Physics. 589. pp. 101–122. doi:10.1007/3-540-46025-X_6. ISBN 978-3-540-43518-1. Bibcode: 2002LNP...589..101F.

- ↑ "Binary Stars and their Importance in Astrophysics". Simple Science. https://scisimple.com/en/articles/2025-08-17-understanding-binary-stars-and-their-importance--a9n8xxp.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Duchêne, Gaspard; Kraus, Adam (August 2013), "Stellar Multiplicity", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 51 (1): 269–310, doi:10.1146/annurev-astro-081710-102602, Bibcode: 2013ARA&A..51..269D. See Table 1.

- ↑ Most Milky Way Stars Are Single, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

- ↑ Hubber, D. A.; A. P. Whitworth (2005). "Binary Star Formation from Ring Fragmentation". Astronomy & Astrophysics 437 (1): 113–125. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042428. Bibcode: 2005A&A...437..113H. https://cds.cern.ch/record/828359.

- ↑ Schombert, J.. "Birth and Death of Stars". University of Oregon. http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/ast122/lectures/lec11.html.

- ↑ "Binary Star Motions". Cornell Astronomy. https://www.astro.cornell.edu/academics/courses/astro201/kepler_binary.htm.

- ↑ Kraus, Adam L.; Ireland, Michael; Mann, Andrew; Huber, Daniel; Dupuy, Trent J. (2017). "The Ruinous Influence of Close Binary Companions on Planetary Systems". American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #229 229: 219.05. Bibcode: 2017AAS...22921905K.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Elisa V. Quintana; Jack J. Lissauer (2007). "Terrestrial Planet Formation in Binary Star Systems". Extreme Solar Systems 398: 201. Bibcode: 2008ASPC..398..201Q.

- ↑ Schirber, M (17 May 2005). "Planets with Two Suns Likely Common". Space.com. http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/050517_binary_stars.html.

- ↑ More circumbinary planets are listed in: Muterspaugh; Lane; Kulkarni; Maciej Konacki; Burke; Colavita; Shao; Hartkopf et al. (2010). "The PHASES Differential Astrometry Data Archive. V. Candidate Substellar Companions to Binary Systems". The Astronomical Journal 140 (6): 1657. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/140/6/1657. Bibcode: 2010AJ....140.1657M.

- ↑ Daemgen, S.; Hormuth, F.; Brandner, W.; Bergfors, C.; Janson, M.; Hippler, S.; Henning, T. (2009). "Binarity of transit host stars – Implications for planetary parameters". Astronomy and Astrophysics 498 (2): 567–574. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200810988. Bibcode: 2009A&A...498..567D. http://www.mpia.de/homes/henning/Publications/daemgen.pdf.

- ↑ See sources at Cygnus X-1

- ↑ McGourty, C. (2005-12-14). "Hubble finds mass of white dwarf". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/4528586.stm.

- ↑ Schlaufman, Kevin C.; Thompson, Ian B.; Casey, Andrew R. (5 November 2018). "An Ultra Metal-poor Star Near the Hydrogen-burning Limit". The Astrophysical Journal 867 (2): 98. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aadd97. Bibcode: 2018ApJ...867...98S.

- ↑ Elisa V. Quintana; Fred C. Adams; Jack J. Lissauer; John E. Chambers (2007). "Terrestrial Planet Formation around Individual Stars within Binary Star Systems". Astrophysical Journal 660 (1): 807–822. doi:10.1086/512542. Bibcode: 2007ApJ...660..807Q.

- ↑ Harmanec, P.; Zasche, P.; Brož, M.; Catalan-Hurtado, R.; Barlow, B. N.; Frondorf, W.; Wolf, M.; Drechsel, H. et al. (2022-04-15). "Towards a consistent model of the hot quadruple system HD 93206 = QZ Carinae - I. Observations and their initial analyses". Astronomy & Astrophysics 666: A23. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142108. ISSN 0004-6361. Bibcode: 2022A&A...666A..23M.

External links

| The Wikibook Glossary of Astronomical Terms has a page on the topic of: binary star |

- IAU Commission G1: Binary and Multiple Star Systems

- List of the best visual binaries for amateurs, with orbital elements

- Pictures and news of binaries at Hubblesite.org

- Chandra X-ray Observatory

- Selected visual double stars and their relative position as a function of time

- AAVSO Eclipsing Binaries section

- OGLE Atlas of Variable Star Light Curves - Eclipsing binaries

|